Evaluation of Sleep in Cancer

Overview of Cancer in Children

Prevalence of cancer is 15 per 100 000 children.1 Neoplasia occurs due to a breakdown of the existing biological balance of cellular renewal and cellular apoptosis/elimination within the body. This disruption is the result of an imbalance of the signaling pathways that control essential cellular functions including cell growth, differentiation and survival.2,3 The majority of cancers are caused by random mutations or alternations to molecular pathways, which increase cancer susceptibility, though some may be the result of hereditary and/or environmental factors. Childhood cancers comprise a wide spectrum of markedly different malignancies, which vary by histology, gender, age, site of origin and race. The most commonly diagnosed childhood cancers are acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) and central nervous system (CNS) malignancies, which comprise 27% and 22% of all childhood cancers, respectively.1 CNS tumors are the most commonly diagnosed solid tumors in children.

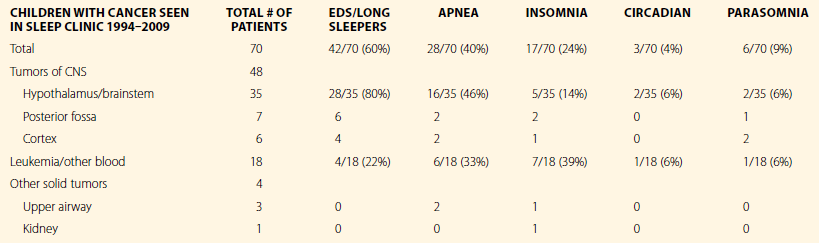

The 5-year survival rate for childhood cancer has dramatically improved over the past 10 years. The overall survival rate averaged across all types of cancers, is about 75%. To achieve this high cure rate, however, children must often endure several years of intensive treatment, which may involve, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgery. Cancer treatment is often a traumatic process requiring frequent and painful procedures or therapies. Morbidity from cancer may be the direct result of the destructive effect of the cancer, or may be from collateral injury to normal tissues caused by toxic treatments. Morbidity in cancer may occur immediately, as a result of acute toxic side effects of treatment, or may develop as the child grows older.4 Some morbidities may not become apparent until well after the cancer has been cured. With respect to sleep-related comorbidity, when investigated, sleep problems have been recognized in children during and after treatment for leukemia5–10 and brain tumors,11,12 the two most common malignancies in children (Table 47.1).

Sleep in Children with Cancer

1. Children with cancer are expected to have the same background prevalence of sleep problems seen in all children.

2. Sleep problems that are the result of the stress on the child and family from the child having a life-threatening disease.

3. Sleep problems that are the direct result of brain injury from brain tumors and CNS-directed therapies including cranioradiotherapy (CRT) for children with brain tumors and leukemia.

4. Sleep problems that are the indirect result of chemotherapy and the many medical complications of cancer including: cancer-related fatigue (CRF), pain, seizures, obesity, endocrinopathies, heart failure, blindness, medication.

There have been no prospective studies of sleep in children with cancer, so the prevalence of sleep problems in this group of children is not known. However, there have been published case series reviews of children with CNS tumors followed in the neurosurgery clinic after surgery,13 children with CNS tumors and other non-CNS malignancies followed in oncology clinics,12 and of children with cancer who were referred for a sleep evaluation because of a sleep complaint identified by their oncologist or primary care doctor.11 Together, these studies provide some insights into the types and frequency of sleep problems in children with cancer.

Sleep problems seen in a study of 70 children with cancer, 48 with CNS tumors, 18 with leukemia or lymphoma, and 4 with solid tumors who were referred for an evaluation and seen over a 15-year period in a single institution, are described in Box 47-1. Sleep problems identified were: excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), present in 60% of the children; apnea, present in 40%; insomnia, present in 24%; parasomnias present in 9% and circadian rhythm disorders present in 4% of the children. More than one sleep problem was identified for many of the children. Excessive daytime sleepiness was the most common sleep problem identified. Parents did not describe EDS as present at the time of diagnosis, but rather developing after the treatment with CNS-directed therapies were instituted. Insomnia was present in 24% of the children, but in most cases was not of great concern to the parents, who viewed it as an inevitable consequence of cancer treatment. Noteworthy in this case series was the distribution of sleep problems seen in children with cancer. This distribution varied significantly from the expected prevalence of sleep problems in children. The type of sleep problem was related to both the type of cancer, and more specifically the location of the cancer, particularly in the case of brain tumors. Although accounting for only 25% of cancers in children, those with brain tumors were the most commonly referred group of children seen in this study, accounting for almost 70% of the referrals. Excessive daytime sleepiness was the most common problem in children with brain tumors, presenting in almost 80% of these children. In contrast, only 22% of the children with leukemia/lymphoma present with EDS as their predominant complaint. In one-third of children with brain tumors and EDS which began after their brain tumor diagnosis, the mean sleep latency on a multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) was greater than 15 minutes. This objective measure of daytime sleepiness would not meet criteria for hypersomnolence as defined by the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd Edition. Nonetheless, these children had a history of an increase in total 24-hour sleep duration, resumption of daytime napping, inability to awaken at the desired morning rise time, and/or an inability to remain awake during daytime activities, all of which began after their cancer diagnosis. When these children were treated with stimulant medication, their symptoms of EDS improved, allowing them to fully participate in the activities of their day.

Sleep in children with cancer is often made worse during hospitalization because of frequent interruptions of the child’s sleep by caregivers. This was described in a study of 29 children with cancer hospitalized for 2–3 days. The children were awakened 0–40 times/night, mean 14. The longest duration of uninterrupted sleep for 70% of the children was 1 hour.14

Neuroanatomy of Sleep and Wakefulness

Sleep and wake are complex neurologic processes which are actively generated by coordinated, overlapping mechanisms controlled by nuclei in the hypothalamus, thalamus, basal forebrain and brainstem.15 Each of these systems controls a different facet of sleep and/or wake, and each has different roles, so the loss of any one system may be partially compensated by other systems. CNS-directed therapies for cancer may impact sleep by direct damage to the brain centers that are responsible for the regulation of sleep–wake by a brain tumor or neurosurgery, or by the neurotoxic effects of CRT and chemotherapy. The relationship between injury to the brain and the development of sleep problems was first described by Von Economo,16 based on his observations of patients with encephalitis. Since Von Economo’s original clinical observations, many other types of injuries to this critical area of the brain have been recognized as causing problems with sleep. The most commonly reported sleep problem after a CNS injury is EDS. Brain injuries that have resulted in EDS have been summarized in a comprehensive review of symptomatic narcolepsy by Nishino and Kanbayashi.17 The 116 cases of symptomatic narcolepsy which have been reported in the literature were associated with: inherited disorders (34%), brain tumors (29%), head trauma (16%), demylenating disorders (9%), stroke (5%), infection (3%), and degenerative disorders (3%). In Nishino’s series, many different types of brain tumors were associated with EDS. Seventy percent of the tumors involved the hypothalamus or adjacent structures including pituitary, supracellar, or optic chiasm, and 10% involved the brainstem. Some tumors involved multiple sites, but in only 12% were areas of the brain other than the brainstem or hypothalamus involved, and in many of these cases CRT was one of the treatments. In 10 of the patients with brain tumors in Nishino’s review, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) hypocretin was measured. Hypocretin was found to be low in 3/10, and normal in 7/10; suggesting that in the majority of cases EDS in patients with brain tumors is not simply caused by the destruction of the hypocretin-secreting cells in the lateral hypothalamus.