Evaluation of Short-Limbed Infants

INTRODUCTION

Evaluation of a newborn with short limbs is often an urgent challenge for the pediatrician and the neonatologist because of the importance of recognizing lethal neonatal skeletal dysplasias, the ability to provide adequate medical management in nonlethal neonatal skeletal dysplasias, and the ability to provide adequate prognostic information to the family during the stages of the initial evaluation. Sometimes, the diagnosis is evident based on physical examination of the newborn, but more often combined information from prenatal ultrasounds, physical examination of the newborn, and skeletal radiographs and other imaging studies is needed to establish a definitive diagnosis.

The evaluation and initial treatment of the neonate who has short limbs and a suspected skeletal disorder require a multidisciplinary approach, usually the expertise of a neonatologist, a medical geneticist, and a radiologist. Other specialty services are involved depending on the associated findings, and these experts typically include otorhinolaryngology, plastic surgery, orthopedic surgery, ophthalmology, as well as neurosurgery services.

Molecular genetic studies are available for some of the more common disorders and can be used to confirm the diagnosis and to provide for a prenatal diagnosis in the future pregnancies of the family, if desired. There are currently more than 400 recognized genetic skeletal disorders, which can be divided into several groups based on molecular, biochemical, or radiographic criteria.1 The molecular etiology is known for approximately 300 of these genetic skeletal disorders,1 providing an opportunity to establish a specific diagnosis and provide accurate prognostic information for the family.

In addition to genetic etiologies of short limbs in newborns, there are nongenetic causes, such as fetal warfarin exposure, which mimics the skeletal phenotype of chondrodysplasia punctatas,2,3 and maternal diabetes, which has been associated with asymmetric shortening of femoral bones because of proximal focal femoral hypoplasia.4,5 These nongenetic etiologies are important to recognize to be able to provide accurate information regarding recurrence risk and, in cases of a teratogen exposure, to be able to prevent recurrence in future pregnancies.

PRENATAL ULTRASOUND IN THE EVALUATION AND DIAGNOSIS OF A FETUS WITH SHORT LONG BONES

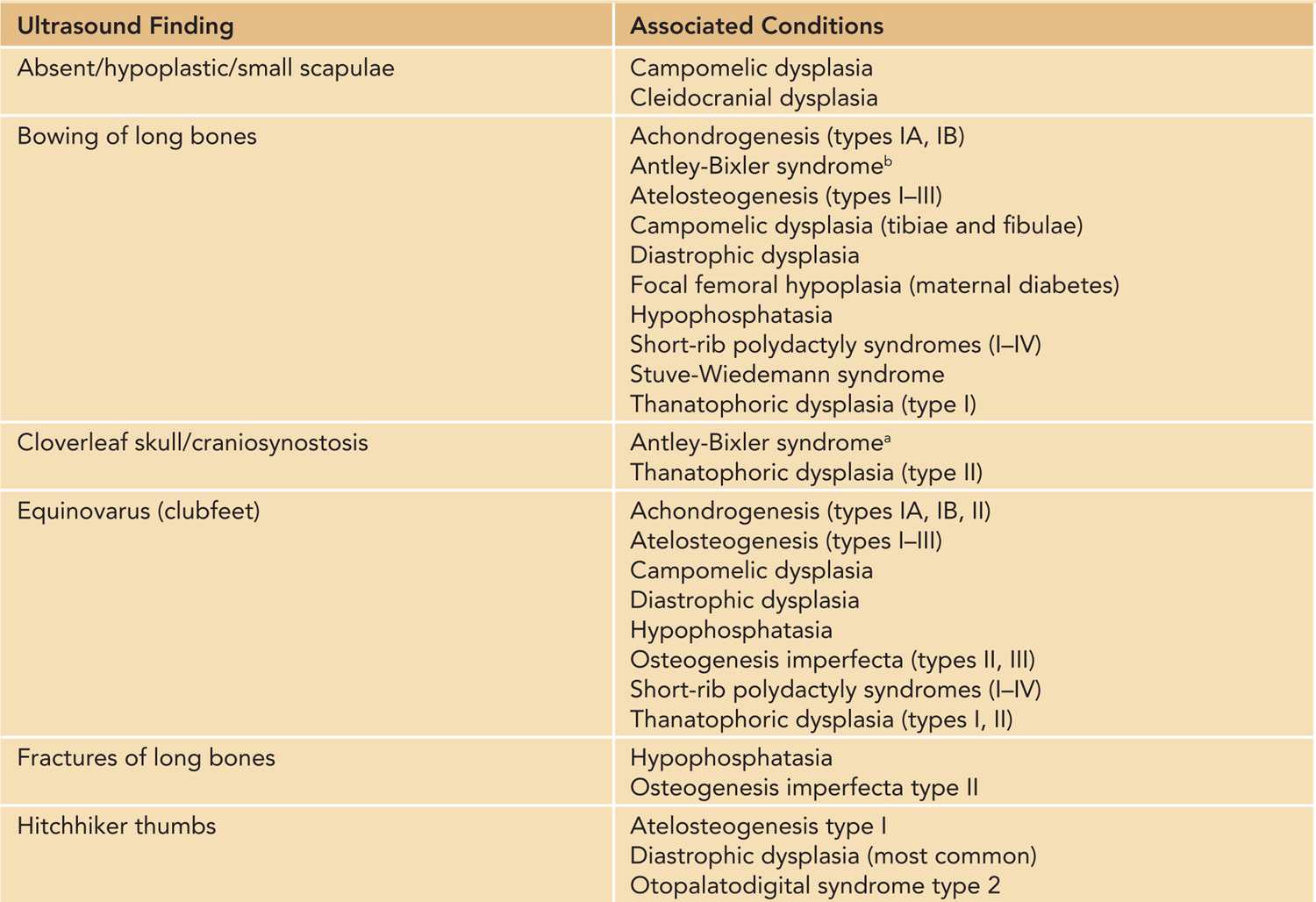

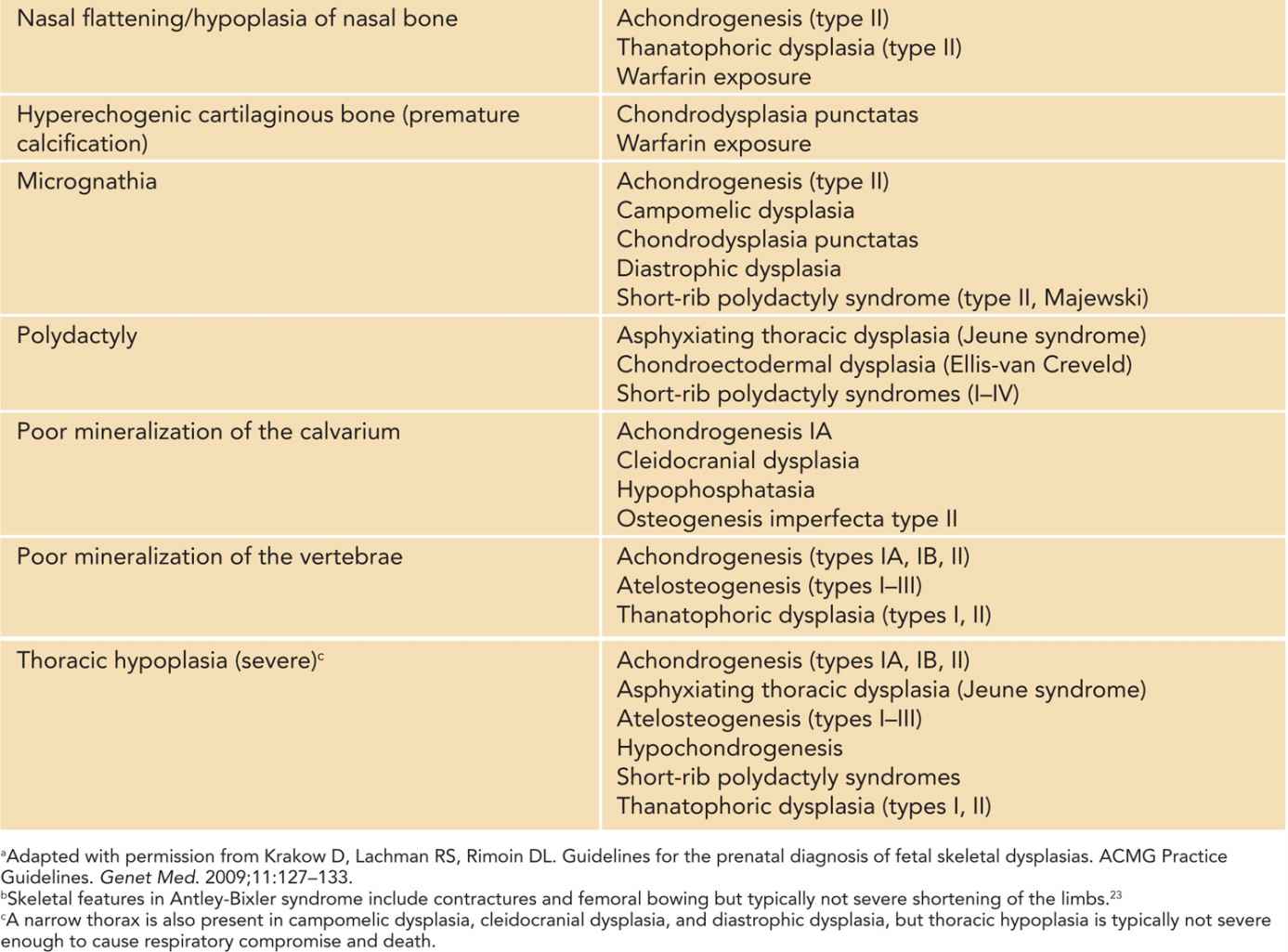

Because many skeletal disorders begin to manifest in fetal development, a suspicion of a congenital skeletal disorder will often be raised during an ultrasonographic evaluation of a fetus in the second trimester. The clavicle, mandible, ileum, scapulae, and long bones ossify by 12 weeks of gestation; the metacarpals and metatarsals by 12 to 16 weeks; and the talus and calcaneus around 22–24 weeks, and epiphyseal ossification centers are seen on radiographs around 20 weeks of gestation.6 Some short-limbed skeletal disorders have characteristic findings that can lead to an accurate diagnosis on a prenatal ultrasonographic examination (Table 119-1).7–9 Early diagnosis of a fetal skeletal disorder during the prenatal period allows time for genetic counseling, may allow for reproductive options for the couple, and helps medical providers plan postnatal care.

Table 119-1 Prenatal Ultrasound Findings and Associated Conditions in a Fetus With a Short-Limbed or Bent-Bone Skeletal Disorder7–9,a

Prenatally, it is important to distinguish between lethal and nonlethal skeletal disorders. Approximately 99% of fetuses with a skeletal dysplasia can have the dysplasia correctly classified as either lethal or nonlethal via prenatal ultrasonography (US).9 Lethality in congenital skeletal disorders is typically related to lung hypoplasia secondary to a narrow thoracic cavity.9,10 Among the nonlethal forms, it is important to diagnose the specific type of skeletal disorder to allow planning for postnatal care. The diagnostic accuracy by prenatal US is the highest among the two most common skeletal dysplasias: thanatophoric dysplasia (TD) and osteogenesis imperfecta (OI).9 Given that respiratory compromise is often a life-threatening possibility in many fetal skeletal dysplasias that present with short long bones in a neonate, in the case of a suspicion of such a skeletal disorder, the delivery should be planned for a center that has expertise to manage respiratory difficulties in a newborn. This expertise typically includes otorhinolaryngology and anesthesiology teams. Other postnatal evaluations and care can also be optimized in a tertiary care center, such as orthopedic (hand and foot deformities), neurosurgical (cervical spine abnormalities), and plastic surgery (cleft palate) evaluations.

FINDINGS ON POSTNATAL PHYSICAL EXAMINATION OF A NEONATE WITH SHORT LONG BONES

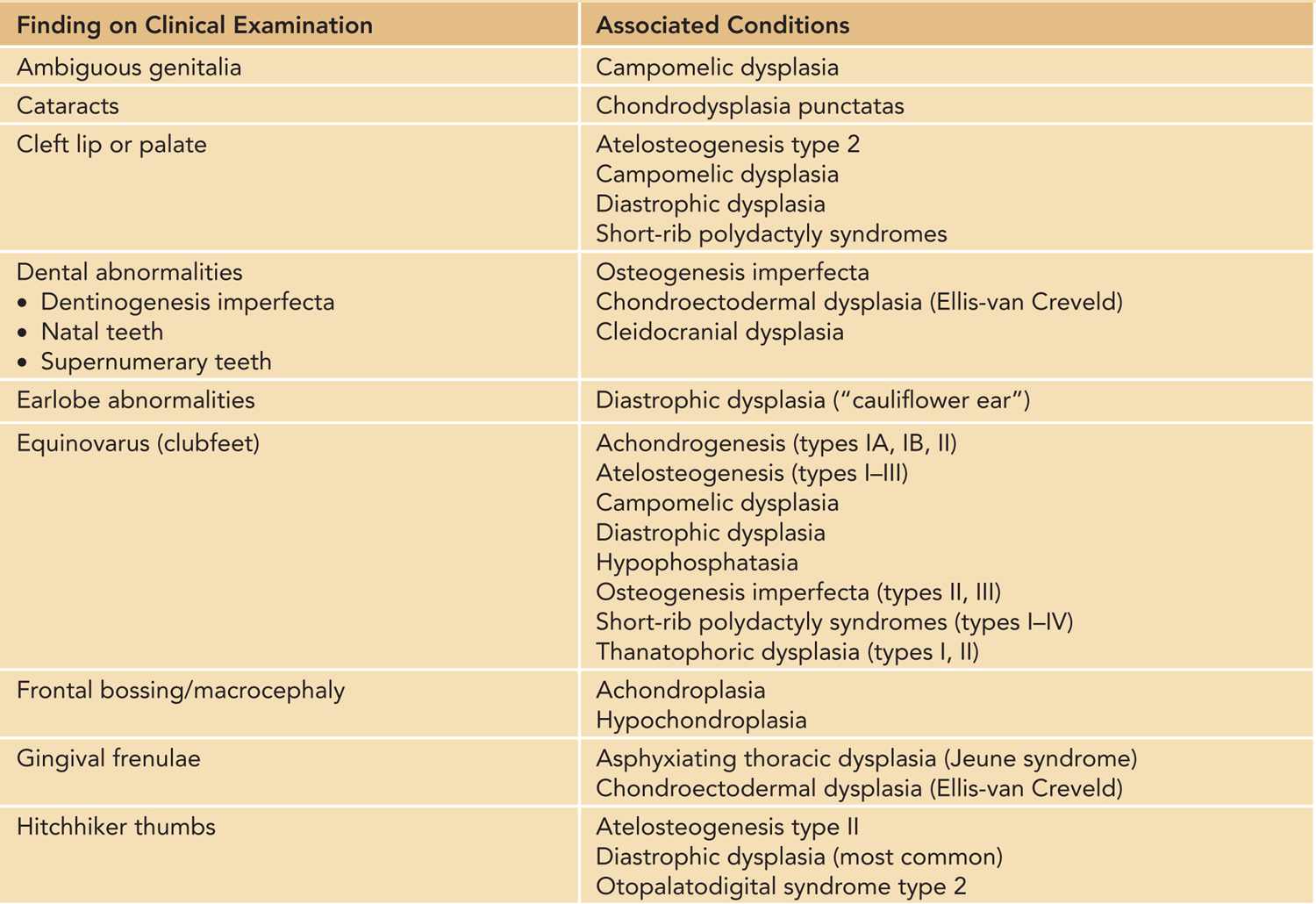

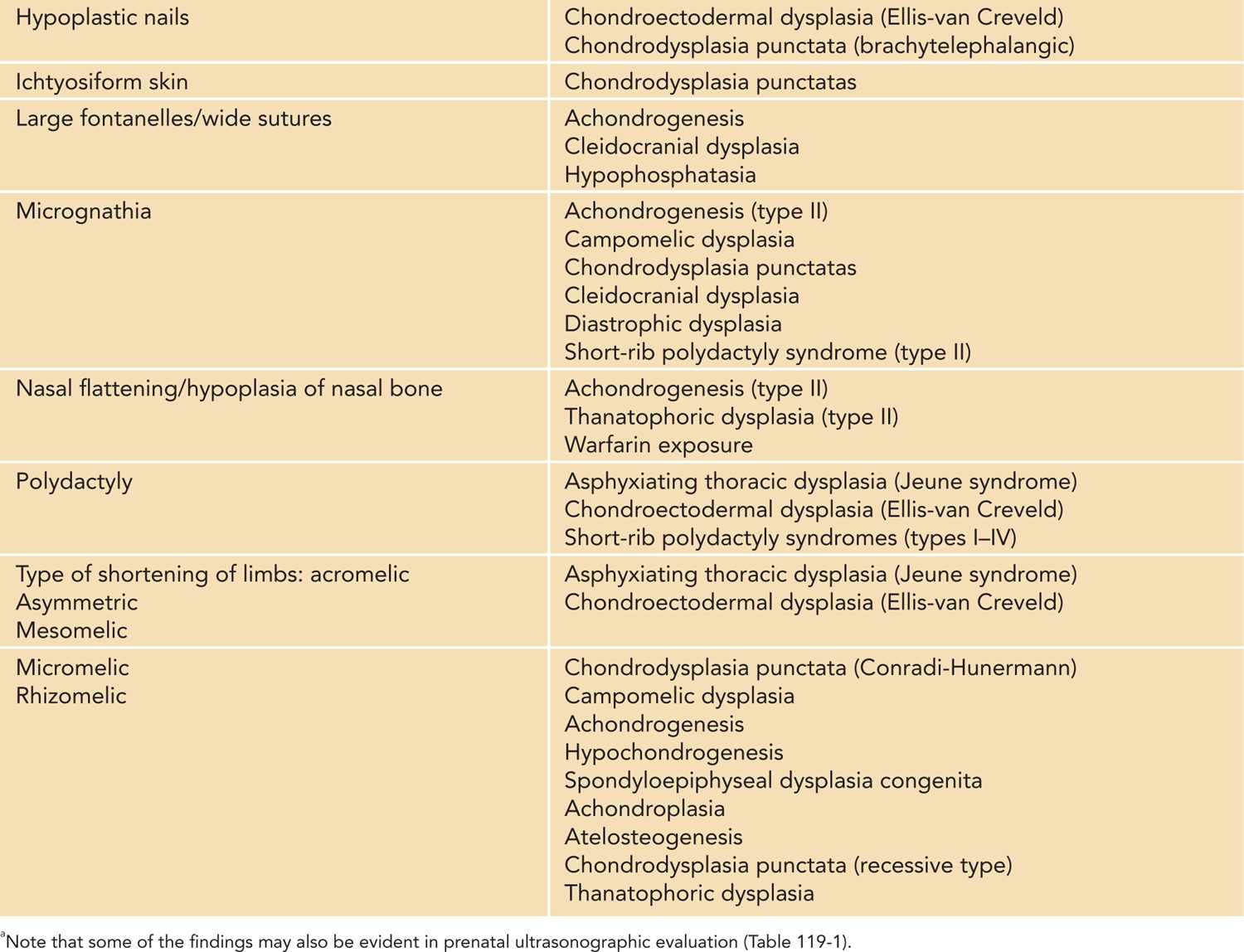

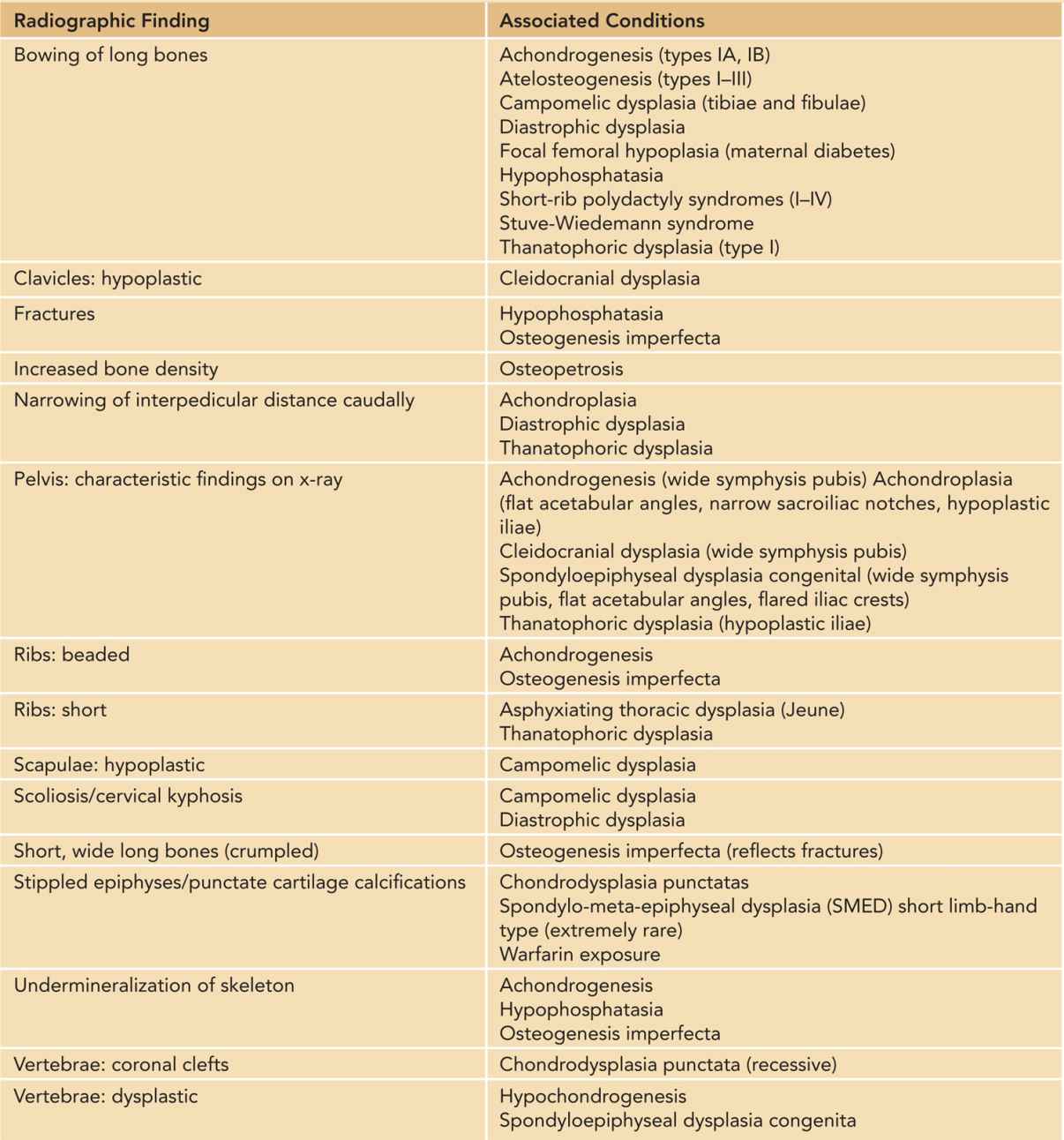

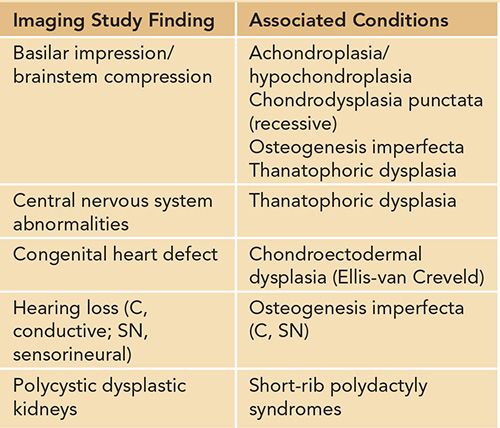

A careful physical examination to look for other major and minor anomalies should be performed in any newborn with short limbs. Findings on physical examination not only may provide diagnostic clues (Table 119-2) but also aid in the initial assessment for the need of medical management and further evaluations by expert teams, such as in the case of a cleft palate. Initial physical examination also guides the need for further imaging studies in the evaluation of a newborn with short limbs. For example, a finding of polydactyly in an infant who has short limbs should prompt a physician to evaluate carefully for cardiac (chondroectodermal dysplasia) or renal (cystic dysplastic kidneys in short-rib polydactyly syndromes) anomalies (Tables 119-2 to 119-4).

Table 119-2 Findings on the Initial Physical Examination of a Newborn With Short Limbs That May Provide Diagnostic Cluesa

Table 119-3 Radiographic Findings on Skeletal X-ray Study in Infants With Short Limbs

Table 119-4 Findings on Other Imaging Studies or Evaluations in Newborns With Short Limbs

There are four main patterns of limb shortening that may be suggestive of a specific skeletal disorder: rhizomelic, mesomelic, acromelic, and micromelic shortening (Table 119-2). Rhizomelic shortening affects the proximal segment of limbs (femur and humerus) and is typical, for example, of autosomal recessive chondrodysplasia punctata.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree