(1)

Department of Urology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

(2)

Department of Surgery (Urology), Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

(3)

Innovative Urological Technology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Abstract

Laparoscopy is a surgical field that has been active for several decades, but many of the harmful, long-term effects of laparoscopy on surgeons are only now being realized. Ergonomics is a field of science applied to work environments with the aim of minimizing risk of injury. In the setting of laparoscopy, ergonomics studies have elucidated some of the current drawbacks of laparoscopy. This chapter evaluates the risk factors, available instruments, and operating room setup for laparoscopic surgery. Additionally, potential solutions and methods of decreasing the risk of injury are examined. By possessing knowledge of the drawbacks of laparoscopy, surgeons may be able to protect themselves and prevent injuries.

Keywords

ErgonomicsLaparoscopyLaparoscopic instrumentSurgeon injuryLaparoscopic surgery is a relatively young field; therefore, some of the long-term effects on surgeons are just starting to be recognized and remain relatively unstudied. The field of study that exists to study negative physical actions in the workplace and find ways to correct them is called ergonomics. Ergonomics is often defined as the “science of fitting the work environment to the worker” [1]. In order to gain knowledge of these effects within the realm of laparoscopic surgery, one must first take note of some differences between laparoscopic surgery and open surgery.

Laparoscopic surgery differs from open surgery in several ways. First, open surgery provides surgeons with a relatively high degree of freedom, allowing the surgeon to work within the natural six degrees of freedom. Laparoscopic surgery, conversely, limits the surgeon to only four degrees [2]. Second, during open surgery, work is done in line with the surgeon’s visual axis. Yet during laparoscopic surgery, the motor actions of the surgeon is decoupled from the visual axis, often causing a mental disconnect. Finally, the surgeon is provided with a 3-dimensional view as well as direct tactile feedback during open surgery. In contrast, a laparoscopic surgeon loses both tactile feedback and depth perception.

These differences pose significant problems for laparoscopic surgeons and often force surgeons to adopt movements and postures in order to overcome some of the mentioned disadvantages. These actions are not always ergonomically correct and are oftentimes associated with improper body posture, difficult repetitive movements of the upper extremities, and prolonged static head and back postures [1].

In general, the laparoscopic surgeon’s posture is an upright position with fewer movements of the back and infrequent weight shifting compared to open surgery. An upright posture consisting of a straight head and back is known to cause strain [3]. Furthermore, because the surgeon’s attention is focused on a monitor during laparoscopic surgery, the surgeon adopts a static posture. Infrequent changes in position allow for maintained pressures on the back, which in turn are associated with increasing fatigue over time [3].

Pain is reported by surgeons to be one of the most commonly experienced problems associated with laparoscopic surgery. A survey of 149 surgeons indicated neck pain and arm pain were experienced in 8 and 12 % of surgeons, respectively [4]. Stiffness of the neck and arms was reported by 9 and 18 %, respectively [4]. Another study found that 20 % of laparoscopic surgeons surveyed experienced upper and lower back pain during surgery and an additional 20 % had shoulder pain and numbness [5]. Moreover, the same study found there was a spectrum in the incidence of pain associated with different types of laparoscopic cases. Hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery had the highest association with injury [5]. Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery had the lowest, and standard laparoscopic surgery fell in the middle [5]. In general, it is suggested that 87 % of laparoscopic surgeons have at some point experienced performance-related symptoms during surgery [6].

Physical strain experienced by surgeons during laparoscopic surgery is real and quite prevalent. In a survey of 260 surgeons, 29 % admitted having had received treatment for physical strain, with half of those requiring physical therapy [7]. Fittingly, of those reporting strain from minimally invasive surgical techniques, only 16 % reported having received ergonomic training [7].

Risk Factors for Surgeon Injury

Several studies have suggested that certain surgeon characteristics are associated with an increased risk of developing morbidity due to performing laparoscopic procedures. Franasiak et al. observed that those at the greatest risk were surgeons of younger age, shorter time in practice, smaller glove size, and shorter stature [7]. It has been reported that laparoscopic surgeons early in their education use 130–138 % greater force and torque when performing laparoscopic surgery compared to their more experienced counterparts [8]. It is rationalized that as a surgeon gains more experience, hand-eye coordination is increased, as does efficiency in handling endoscopic instruments [8].

Similarly, it has been reported that finger numbness and eyestrain are less common in experienced surgeons. Hemal et al. showed that 13 and 16 % of surgeons with greater than 2 years of experience reported finger numbness and eyestrain, respectively, compared to 31 and 40 % of surgeons with less than 2 years of experience [9]. The authors suggested that surgeons first starting out in their career may not have received proper ergonomic training during their surgical education and that over time, they learned through experience to adjust their technique to decrease symptoms [9].

In contrast, Park et al. report that the single most predictive risk factors for the development of laparoscopic surgery-related symptoms were in those surgeons with the highest laparoscopic case volumes. The surgeon’s age or years of laparoscopic experience did not seem to have a significance of an impact [6]. The available evidence, although somewhat conflicting, shows that there are main factors that can be targeted in hopes of decreasing the risk of laparoscopy-induced injuries for surgeons.

Laparoscopic Instruments and Their Ergonomics

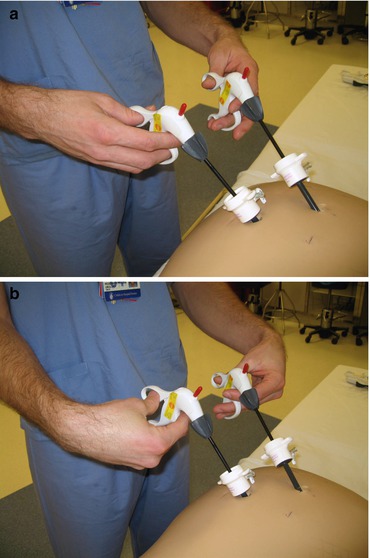

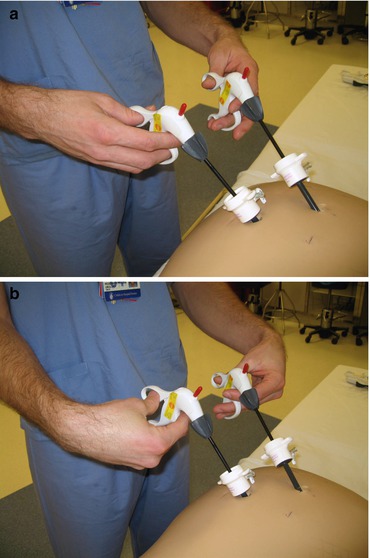

Current laparoscopic instruments were adopted from those used in procedures minimally related to their current use. EMG studies demonstrated that the use of laparoscopic instruments can increase muscular work of the forearm and thenar compartment by a factor of 2–5 compared to using a standard hemostat [4]. Further studies indicated that when using laparoscopic instruments, EMG percentages exceeded accepted threshold limits, suggesting that the muscles were working in excess of their ability to avoid fatigue [10]. Nonergonomic instruments can promote many uncomfortable movements and maneuvers. For example, the wrists can be forced into a flexed position with ulnar deviation (Fig. 2.1a, b) [11]. This movement moves the surgeon out of the neutral position and can cause compression of the median nerve.

Fig. 2.1

(a) Proper wrist angle. (b) Improper wrist angle increasing pressure on the carpal tunnel

Nerve compression is a major concern for laparoscopic surgeons. The development of neuropraxia has been commonly attributed to performing laparoscopic procedures. Prolonged pressure of the radial digital nerve of the thumb and the palmar branch of the median nerve is a relatively common cause of digital neuropraxia [12]. In a survey of 50 laparoscopic surgeons, 40 % had experienced neuropraxia with symptoms lasting a median of 9 h and occurring a median of 4.5 different times [13]. There was a direct correlation between the frequency and total number of cases performed annually [13]. It is theorized that in an effort to perform precise movements and reduce tremor, surgeons will maintain an excessively forceful grip of the instrument compressing digital nerves [13].

These major drawbacks of the laparoscopic instruments can be attributed to their present design. Instrument shape poses a major problem for surgeons. The style of the most commonly used laparoscopic instruments possesses a scissor style with a pistol grip which requires thumb manipulation [14]. Furthermore, in the same study, Van Veelen et al. defined the ergonomic requirements for laparoscopic instruments and noted that the design of that most common style only met three out of the eight ergonomic requirements that they defined [14]. It has been observed that the scissor-handle type of laparoscopic instruments is associated with excessive wrist excursions during high-precision tasks and the cylindrical-handle type is associated with excessive wrist excursions during global tasks [15]. Moreover, laparoscopic instruments often possess narrow contact surfaces that are not ideal for accommodating the surgeons’ hands and fingers [11]. This puts pressure on small areas of the fingers that can eventually lead to numbness during the case.

The force required during the use of laparoscopic instruments is another major problem. When using the laparoscopic instrument, force must be applied, extending down the length of the instrument to the tip. This correlates with a force requirement of 4–6 times that of open surgery instruments [2]. This creates a problem for surgeons with busy caseloads as high forces must be maintained consistently during surgery, which can quickly result in fatigue. Force creation has been found to be a significant problem for surgeons with relatively small hands. Those with a glove size of 6.5 or smaller have been observed to experience significantly more difficulty with the use of laparoscopic instruments [16]. This is troubling as 36 % of the study group had a glove size of 6.5 or less [16]. Glove size ranges from 5.5 to 9 at increments of 0.5, yet there exists only one size of laparoscopic instrument [6]. Surgeons could potentially benefit from having the option of choosing from a collection of differently sized laparoscopic instruments.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree