Endocrine Abnormalities Causing Growth Impairment

Edward O. Reiter

Most children with deficient pituitary function secrete inadequate amounts of growth hormone (GH); therefore, the term hypopituitarism is used interchangeably with growth hormone deficiency (GHD). Children who have diabetes insipidus caused by isolated deficiency of antidiuretic hormone (discussed in Chapter 525) and those uncommon children who have isolated gonadotropin deficiency (Kallmann syndrome; see Chapter 541) are exceptions. They have normal GH secretion but pituitary dysfunction of posterior and anterior pituitary lobes, respectively. GHD is the most common endocrinologic cause of the insulin-like growth factor deficiency (IGFD) syndrome.

Deficiency of GH can occur alone (isolated GHD) or in conjunction with overt deficiency of one or more other pituitary hormones (the term panhypopituitarism refers to multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies). Although there are exceptions, patients with multiple pituitary hormonal deficiencies tend to have more severe GHD.

GROWTH HORMONE DEFICIENCY (HYPOPITUITARISM)

EPIDEMIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The best estimate of incidence of GHD in the US population is often cited as being about 1:3480. However, acquired, idiopathic, isolated GHD may be overdiagnosed. Growth hormone (GH)-treated patients with GHD (as defined by a stimulated GH level of < 10 ng/mL) account for about 60% of all treated patients of whom 78% have “idiopathic” GHD and 22% have “acquired” or “organic” (neoplasms, trauma, inflammation, miscellaneous) causes of GHD.

Around 300 patients with inherited abnormalities of the GH receptor have been identified. Potentially, a larger group of individuals with heterozygous abnormalities of the GH receptor will be added to this group with abnormalities such as defects of GH receptor signaling (JAK-STAT) and defects of the insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) gene.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF GROWTH HORMONE DEFICIENCY (HYPOPITUITARISM)

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF GROWTH HORMONE DEFICIENCY (HYPOPITUITARISM)

The causes of hypopituitarism include disorders of the pituitary gland and hypothalamic disorders that impair the release of growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH), as listed in Table 523-1.

Hypothalamic Dysfunction

Idiopathic hypopituitarism with growth failure due to growth hormone deficiency (GHD) may appear at the end of the first year after birth. This disorder has been postulated to be due to brith complications because as many as 70% of children with idiopathic hypopituitarism have histories of some form of perinatal insult, such as hypoxia from maternal bleeding, breech delivery, or asphyxia during the birth process. However, in at least 30% of these patients, abnormalities of the pituitary stalk, an ectopic posterior pituitary gland, or anterior pituitary hypoplasia are demonstrated with imaging studies. Therefore, it seems more likely that the perinatal difficulties in GHD children are a consequence, rather than a cause, of the hypopituitarism. These children are able to secrete growth hormone (GH) in response to the injection of growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH), and can secrete thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) in response to thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH). Deficiency of GH may also be associated with a variety of midline central nervous system and facial developmental defects, including holoprosencephaly, cleft lip, and cleft palate. Hypopituitarism also can occur in association with hypotelorism or single upper central incisor.

Septooptic dysplasia is a form of midfacial central nervous system hypoplasia in which GH deficiency and other pituitary hormone deficiencies are associated with small optic disc, nystagmus, blindness, and often absence or underdevelopment of the septum pellucidum. There is an increased incidence in offspring of young mothers, in first-born children, in areas of high unemployment, and in babies exposed to intrauterine medications, smoking, alcohol, and diabetes. Mutations of HESX1, a paired-like homeodomain gene expressed early in pituitary and forebrain development, are associated with familial forms of septooptic dysplasia.

Table 523-1. Causes of Growth Hormone Deficiency Leading to Insulin-like Growth Factor Type I Deficiency Syndrome

Hypothalamic Disorders: Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone Deficiency |

Developmental abnormalities |

Infundibular dysgenesis (anterior pituitary hypoplasia, stalk attenuation or absence, ectopic posterior pituitary); often associated with birth trauma and other forms of perinatal insult |

Midline central nervous system and facial developmental defects: septooptic dysplasia, holoprosencephaly, cleft lip or palate, single upper central incisor |

Infection |

Histiocytosis |

Hypothalamic tumor |

Craniopharyngioma |

Hamartoma |

Neurofibroma |

Glioma |

Germinoma |

Psychosocial dwarfism |

Idiopathic disorder |

Disorders of the Pituitary Gland |

Aplasia, hypoplasia |

Genetic syndromes: deletion of the growth hormone gene, familial panhypopituitarism and familial isolated growth hormone deficiency |

Intrasellar tumor: craniopharyngioma, adenoma |

Nontumorous destruction: Infarction associated with trauma, infection, or irradiation of the head |

Genetic Causes of Growth Hormone Deficiency

Inherited genetic defects are associated with growth hormone deficiency (GHD) and hypopituitarism (Table 523-2); as many as 3% to 30% of children with GHD have an affected parent, sibling, or child. A variety of coding defects for transcription factors led to a failure of development of the pituitary cells.

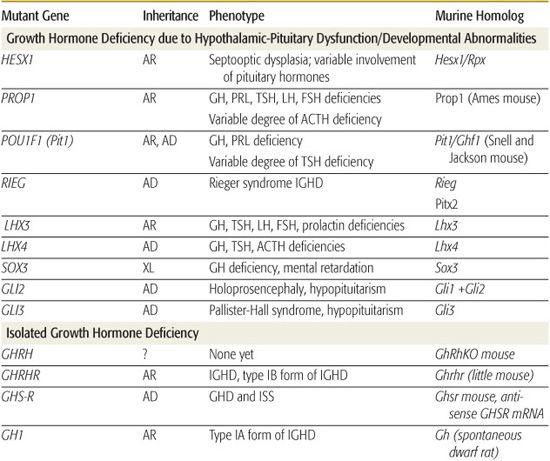

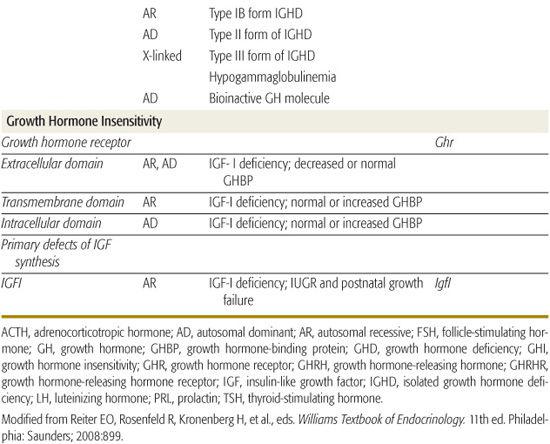

Table 523-2. Genetic Defects of the Growth Hormone-Insulin-like Growth Factor Axis Resulting in Insulin-like Growth Factor Deficiency

Abnormalities of human PROP1 result in multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies (MPHDs), characterized by variable and often age-dependent degrees of deficiency of growth hormone (GH), prolactin, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), leuteinizing hormone (LH), and, occasionally, adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH). Gonadotropin abnormalities are particularly variable such that approximately 30% of patients have spontaneous pubertal development, including menarche, before ultimately developing hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Pituitary size varies among patients and through life so that it may be very large and then involute leaving an empty sella. ACTH deficiency may not develop until the fourth or fifth decade of life.  Large-scale screening of patients with MPHDs has found 54% with PROP1 mutations, but there appears to be substantial geographic variation in associated genetic defects.

Large-scale screening of patients with MPHDs has found 54% with PROP1 mutations, but there appears to be substantial geographic variation in associated genetic defects.

Specific mutations, especially deletions, in the gene encoding GH, some with abnormalities that produce a bioinactive GH, have been described. No examples of mutations of the gene encoding growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) have been identified, but multiple kindreds with homozygous mutations of the GHRH-receptor gene have been identified; these patients have marked short stature, but lack other features of GHD, such as microphallus, truncal obesity, and hypoglycemia.

Cranial Irradiation

There are as many as 4000 pediatric cancer survivors who have growth hormone deficiency (GHD) resulting from a broad range of cancer treatments. Following cranial irradiation, GHD may evolve over years; thus, diagnosis may require serial testing. Some patients with auxology suggestive of GHD may have insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and/or insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 (IGFBP-3) levels below the normal range on repeated tests, but growth hormone (GH) responses in provocation tests remain above the “cut-off” level. Such children do not have classical GHD, but nonetheless may have an abnormality of the GH/IGF axis and may benefit from GH treatment.

Radiation may impair both hypothalamic and pituitary function; however, in the dosing range usually given to children with malignancy, hypothalamic damage is more common. Low doses typically cause isolated GHD, and higher doses may cause multiple pituitary deficiencies. The majority of long-term survivors develop GHD with the adverse effect of radiotherapy directly related to the biologically effective dose to the hypothalamus. Within 5 years of radiation, nearly 100% of children receiving ≥ 30 Gy over 3 weeks to the hypothalamic-pituitary axis have subnormal GH responses to provocative tests, whereas GHD may not become apparent for a decade or more after lower doses (18-24 Gy). Even when serum GH responses to provocative testing are normal, spontaneous GH secretion may be blunted at x-ray doses as low as 18 to 24 GY.

Poor linear growth from decreased GH secretion may be exacerbated by the impact of radiation itself, with inadequate pubertal acceleration of spinal growth. Surprisingly, cranial radiation can also result in precocious puberty, especially in children irradiated at young ages, causing early epiphyseal fusion. Sexual precocity appears to occur more frequently with low doses of radiation, and gonadotropin deficiency is likely at high doses. Treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogs may be necessary to suppress the hypothalamic-pituitary gonadal axis in an attempt to attain normal final height.

Bone marrow transplantation (BMT) for patients with inborn errors of metabolism, aplastic anemias, and malignancies requires preparative regimens that include total lymphoid or total body radiation, often with chemotherapy, and sometimes including cranial radiation. In children who had cranial radiation followed by high-dose chemotherapy and total body radiation as preparative regimens, growth failure is almost inevitable 2 to 5 years after BMT.

Neoplasms

Craniopharyngiomas are the most common neoplastic cause of pituitary insufficiency in children. This tumor is a congenital malformation present at birth and gradually grows over the ensuing years. About 75% of craniopharyngiomas arise in the suprasellar region, the remainder resembling pituitary adenomas. Most often, symptoms of headaches, vomiting, visual disturbances, symptoms of diabetes insipidus, and a change in sensorium result from the central nervous system involvement by the tumor. Fifty percent to 80% of patients have abnormalities of at least one anterior pituitary hormone at diagnosis. Many children or adolescents have evidence of growth arrest that may have begun near infancy and/or pubertal delay.  Hypothalamic gliomas, often associated with neurofibromatosis, and germinomas can cause pituitary insufficiency and many of the neurologic signs of craniopharyngioma. Microadenoma of the pituitary can occur with Cushing syndrome (see Chapter 535) and can cause hypopituitarism by compressing adjacent normal pituitary tissue. Following transsphenoidal resection, those with a macroadenoma have about a 50% incidence of hypopituitarism, whereas those with microadenomas have normal pituitary function; long-term cure rates are 55% to 65% for both tumor sizes.

Hypothalamic gliomas, often associated with neurofibromatosis, and germinomas can cause pituitary insufficiency and many of the neurologic signs of craniopharyngioma. Microadenoma of the pituitary can occur with Cushing syndrome (see Chapter 535) and can cause hypopituitarism by compressing adjacent normal pituitary tissue. Following transsphenoidal resection, those with a macroadenoma have about a 50% incidence of hypopituitarism, whereas those with microadenomas have normal pituitary function; long-term cure rates are 55% to 65% for both tumor sizes.

Other Acquired Conditions

Decreased growth and impaired pubertal maturation may be seen in up to 60% of children and adolescents who have suffered mild to severe head injury. Growth hormone (GH) secretory defects are seen in psychosocial dwarfism, and extreme form of “failure to thrive” due to emotional deprivation. After the children spend a brief period in a supportive environment, pituitary function improves remarkably, and linear growth is accelerated. Empty sella syndrome is an uncommon disorder among children. It occurs when the diaphragma sellae does not surround the pituitary stalk tightly. The result is herniation of the arachnoid into the pituitary fossa and compression of normal pituitary tissue onto the walls of the sella turcica. The sella turcica can be expanded, and intrasellar hypodensity may be apparent by CT. Many patients with empty sella syndrome have no symptoms or signs of pituitary dysfunction but some do have associated pituitary hypofunction. The prevalence of empty sella syndrome increases among patients with pituitary adenoma. Localized (hypothalamus, pituitary) or generalized proliferation of mononuclear macrophages (histiocytes) characterizes Langerhans cell histiocytosis, a diverse disorder occurring at all ages, with peak incidence at ages 1 to 4 years (see Chapter 463). Approximately 50% to 75% of patients with one of these disorders, Hand-Schüller-Christian, have diabetes insipidus, But growth hormone deficiency (GHD) is rare.

Table 523-3. Clinical Features of Growth Hormone Deficiency or Growth Hormone Insensitivity