Background

Paralytic ileus that develops after elective surgery is a common and uncomfortable complication and is considered inevitable after an intraperitoneal operation.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether coffee consumption accelerates the recovery of bowel function after complete staging surgery of gynecologic cancers.

Study Design

In this randomized controlled trial, 114 patients were allocated preoperatively to either postoperative coffee consumption with 3 times daily (n=58) or routine postoperative care without coffee consumption (n=56). Total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with systematic pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy were performed on all patients as part of complete staging surgery for endometrial, ovarian, cervical, or tubal cancer. The primary outcome measure was the time to the first passage of flatus after surgery. Secondary outcomes were the time to first defecation, time to first bowel movement, and time to tolerance of a solid diet.

Results

The mean time to flatus (30.2±8.0 vs 40.2±12.1 hours; P <.001), mean time to defecation (43.1±9.4 vs 58.5±17.0 hours; P <.001), and mean time to the ability to tolerate food (3.4±1.2 vs 4.7±1.6 days; P <.001) were reduced significantly in patients who consumed coffee compared with control subjects. Mild ileus symptoms were observed in 17 patients (30.4%) in the control group compared with 6 patients (10.3%) in the coffee group ( P =.01). Coffee consumption was well-tolerated and well-accepted by patients, and no intervention-related side-effects were observed.

Conclusion

Coffee consumption after total abdominal hysterectomy and systematic paraaortic lymphadenectomy expedites the time to bowel motility and the ability to tolerate food. This simple, cheap, and well-tolerated treatment should be added as an adjunct to the postoperative care of gynecologic oncology patients.

Postoperative paralytic ileus (POPI) that develops after elective abdominal surgery is a common and uncomfortable complication that is considered inevitable after an intraperitoneal operation. The incidence of POPI in patients who undergo pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy (PPL) to treat gynecologic malignancies is 10.6–50%. POPI contributes to patient discomfort, causes nausea, vomiting, and abdominal distension, and prolongs the hospital stay. This increases the risk for hospital-acquired infections, deep-vein thrombosis, and pulmonary compromise. POPI also increases hospital costs and the 30-day readmission rate.

Despite the high incidence of ileus, preventative therapeutic options remain limited. Many efforts that include the administration of prokinetic compounds (such as serotonin receptor antagonists, neostigmine, alvimopam, and ghrelin agonists ), early resumption of feeding, gum chewing, and adequate pain control have been made to prevent ileus. Unfortunately, none of these strategies has been completely successful.

Coffee is a popular drink worldwide and has various effects on medical conditions. Two reports have shown that coffee consumption after colectomy is both safe and associated with significantly faster resumption of intestinal motility. Another study on the same topic remains ongoing. However, no study has yet investigated the effects of coffee on gastrointestinal function in patients who have undergone surgery to treat gynecologic cancers, according to a systematic review of the literature (through PubMed, OvidSP, Google Scholar, and Scopus; Medline was searched from 1966 to July 2016 with the use of the following MeSH terms: ileus, coffee, gynecology). Thus, we explored the effects of coffee on postoperative bowel function in patients who had undergone either total or radical hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and systematic PPL to determine the stage of gynecologic cancers.

Materials and Methods

This randomized controlled study was conducted at the Tepecik Education and Research Hospital, Department of Gynecological Oncology, Izmir, Turkey, between November 2013 and February 2016. Ethical approval was obtained from the Istanbul Kanuni Sultan Suleyman Education and Research Hospital Ethics Committee (reference number: 10/2013). Additionally, the study was registered with clinicaltrials.gov (no. NCT01990482 ).

Patients who had received a diagnosis of cervical, endometrial, or ovarian cancer and scheduled for comprehensive staging surgery (abdominal hysterectomy and systematic PPL) were recruited. The exclusion criteria were any known hypersensitivity or allergy to caffeine/coffee, a thyroid disease, inflammatory bowel disease, compromised liver function, clinically significant cardiac arrhythmia, chronic constipation (defined as ≤2 bowel movements per week), a history of abdominal bowel surgery, previous abdominal irradiation, previous neoadjuvant chemotherapy or hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy, a need for intensive care for >24 hours postoperatively, a need for nasogastric tube drainage beyond the first postoperative morning, a bowel anastomosis, and the use of an upper abdominal multivisceral surgical approach for debulking surgery.

The study details were explained to all enrolled subjects. All participants gave written informed consent before inclusion in the trial. Randomization was performed when the patients were admitted to our gynecologic oncology clinic. Eligible patients were assigned randomly to 1 of 2 groups by a primary investigator (K.G.) who consecutively opened sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. Caffeine and nicotine consumptions were recorded. Envelope randomization was performed with the use of a computer-generated code running a blocked randomization protocol. Group A served as the control group and received no treatment; group B (the coffee group) drank 3 cups of caffeinated coffee daily (100 mL at 10:00 am , 3:00 pm , and 7:00 pm ), beginning on the morning after surgery. Patients were asked to drink the entire 150-mL amounts within 20 minutes under the supervision of a nurse or doctor. Patients were free to drink any amount of water but no more coffee, black tea, or other form of caffeine, such as soda. Coffee was prepared with a conventional coffee machine (Nescafe Alegria; 100 g caffeine; Nestlé. Gatwick, United Kingdom).

After enrollment, we implemented a standard clinical protocol. Before operations, all patients who were scheduled for comprehensive staging surgery ingested a clear liquid diet and underwent mechanical bowel preparation with 20 g MgO (Magnesi-Kalsine Toz; İstanbul İlaç, Istanbul, Turkey) and 28.5 g NaH 2 P with 10.5 g Na 2 HP (BT Enema; Yenisehir Laboratory, Ankara, Turkey), low-molecular-weight heparin, and prophylactic intravenous antibiotics at the time of induction of anesthesia. All patients underwent the same anesthetic protocol (in general, propofol and Tracrium were administered intravenously, and sevoflurane and nitrous oxide were administered by inhalation with epidural catheter analgesia).

All patients underwent total abdominal hysterectomy with systematic PPL as part of their staging procedures. All operations were performed by the same surgical team. Our postoperative care protocol featured the administration of the prokinetic agent metoclopramide (as an antiemetic), if required, and prophylaxis for stress-induced gastritis in the form of histamine H 2 blockers for 48 hours after surgery. All patients received steady oral paracetamol for 48 hours after operation, after removal of the epidural catheter. Additional nonsteroidal analgesia was provided when required, and its use was carefully documented. Antiemetic agents were prescribed for nausea, if required. No opioid antagonists were used postoperatively. Early ambulation was encouraged; all patients were mobilized after assuming a sitting position in bed for 10 minutes to prevent hypotension, starting from 24 hours after surgery; patients walked approximately 5–10 meters. The postoperative feeding regime was standardized; a liquid diet was begun on the first postoperative day and progressed to a regular diet within the next 24 hours, as tolerated.

The defined primary outcome measure was the time to the first passage of flatus after surgery. The secondary outcomes were the time to first defecation, time to first bowel movement, time to toleration of a solid diet, any potential side-effects of postoperative coffee intake, whether antiemetics were needed on the morning after surgery, whether analgesics in addition to those used in our clinic routine were required, POPI type and rate, and the length of hospital stay.

The time to tolerance of a solid diet was measured from the end of surgery (defined as when the patients woke up from anesthesia) until the patient tolerated the intake of solid food (any food that required chewing) without vomiting or experiencing significant nausea within 4 hours after the meal and without reversion to enteral fluids only. The time to the first bowel movement was defined as the time to the first audible bowel sound during routine postoperative treatment.

POPI was considered to be resolved after the first passage of flatus if abdominal distension and vomiting were both absent. The symptoms were categorized as mild if they resolved spontaneously within a few days with only observation and basic support, moderate if vomiting persisted and reinsertion of the nasogastric tube was clinically required, and severe if symptoms persisted for >2 days or resisted treatment.

The symptoms and signs of ileus were evaluated 3 times daily by an evaluator who was blinded to the study allocation. To monitor the recovery of bowel function precisely, patients were instructed to notify ward nurses or investigators immediately after the first occurrence of flatus, bowel movement, or defecation. We also checked all bowel sounds 6 times daily.

Unfortunately, complete blinding after the assignment of the interventions could not be achieved because of the nature of the study. The hospital discharge criteria were stable vital signs with no fever (defined as body temperature ≥38.5°C) for at least 24 hours, the ability to ambulate without assistance, the ability to tolerate solid food without vomiting, normal urination and defecation, and the absence of any complications after surgery.

At the start of the trial, all studies to date that had explored coffee intake had included only patients who had undergone colonic surgery. Thus, we ran a nonblinded pilot trial of 20 patients in each group (A and B) before the full trial. The mean time to flatus was 43.7±13.3 hours in group A and 31.7±6.9 hours in group B. Based on these data, we calculated that, to attain a study power of 90% with an α level of .05, 49 patients were required in each group. Assuming a 20% dropout rate, 118 patients were required.

Whether variables were distributed normally was examined with the use of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The χ 2 and Fisher’s tests were used to compare categoric variables; the Student t test was used to compare normally distributed continuous variables, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare variables that were not normally distributed. Odds ratios were estimated with the use of Cox’s proportional hazard modeling. Statistical analyses were performed with the use of Med Calc (version 16.4; Ostend, Belgium). We used an intention-to-treat protocol. A probability value of <.05 was considered significant.

Results

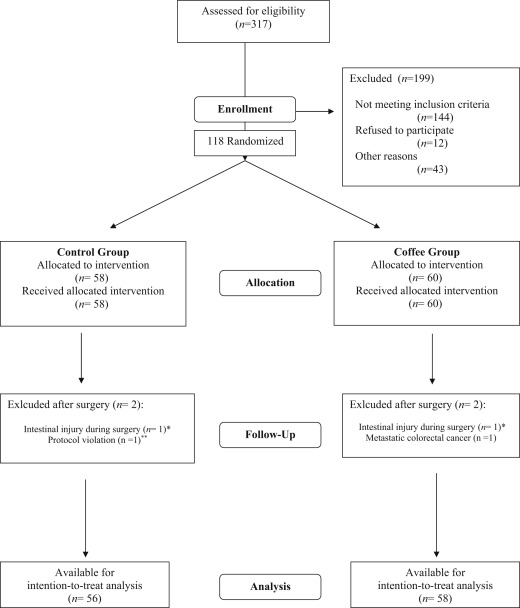

During the study period, in total, 118 patients were enrolled; 60 patients were assigned randomly to the coffee group, and 58 were assigned to the control group. Four patients (2 in the control group and 2 in the treatment group) were excluded after randomization because they no longer fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Ultimately, the conditions of 56 patients in the control group and 58 in the coffee group were analyzed. The reasons for exclusion before and after randomization are shown in the Figure . The patient characteristics of each group were comparable and are shown in Table 1 . In both groups, endometrial cancer (50.0% in the control vs 55.2% in the coffee group) was the most common indication for comprehensive staging surgery.

| Characteristic | Control group (n=56) | Coffee group (n=58) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y a | 53.1±11.4 | 56.6±10.1 | .09 |

| Body mass index, kg/m 2 a | 27.4±3.6 | 27.9±4.1 | .48 |

| Gravida a | 2.3±1.0 | 2.5±1.4 | .26 |

| Tobacco use, n (%) | 4 (7.1) | 6 (10.3) | .74 |

| Ethanol use, n (%) | 1 (1.8) | — | .49 |

| Coffee drinker, n (%) | 12 (21.4) | 14 (24.1) | .73 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 8 (14.3) | 12 (20.7) | .46 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 7 (12.5) | 9 (15.5) | .78 |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 2 (2.6) | 3 (5.2) | 1.00 |

| Other comorbid disease, n (%) | 5 (8.9) | 4 (6.9) | .74 |

| Indication for surgery, n (%) | .69 | ||

| Endometrial cancer | 28 (50.0) | 32 (55.2) | |

| Ovarian cancer | 24 (42.9) | 21 (36.2) | |

| Cervical cancer | 2 (3.6) | 4 (6.9) | |

| Fallopian tube cancer | 2 (3.6) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Previous abdominal surgery, n (%) | 9 (16.1) | 11 (19.0) | .80 |

The types of operative procedures for both the coffee and control groups are shown in Table 2 . Two patients (3.6%) in the control group and 4 patients (6.9%) in the coffee group underwent type III radical hysterectomy and systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy and paraaortic lymphadenectomy up to the inferior mesenteric artery to treat cervical carcinoma. The durations of operations were similar between the groups ( P =.63). Metoclopramide 10 mg was used by 15 patients (28.8%) patients in the control group and by 10 patients (17.2%) in the coffee group ( P =.15).

| Characteristic | Control group (n=56) | Coffee group (n=58) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hysterectomy type a , n (%) | .37 | ||

| I | 45 (80.4) | 49 (84.5) | |

| II | 9 (16.1) | 5 (8.6) | |

| III | 2 (3.6) | 4 (6.9) | |

| No. of removed lymph node b | |||

| Pelvic | 24.6±10.6 | 26.8±10.5 | .25 |

| Paraaortic | 21.3±9.8 | 20.6±7.7 | .69 |

| Omentectomy, n (%) | 40 (71.4) | 39 (67.2) | .62 |

| Peritonectomy, n (%) | 8 (14.3) | 10 (17.2) | .79 |

| Appendectomy, n (%) | 3 (5.4) | 5 (8.6) | .71 |

| Duration of operation, min b | 196.7±47.6 | 200.5±34.0 | .63 |

| Duration of anesthesia, min b | 218.4±47.1 | 222.6±35.2 | .58 |

| Blood transfusion, n (%) | 5 (8.9) | 4 (6.9) | .74 |

Coffee consumption was well-tolerated by all patients. Furthermore, no adverse events were observed in the context of coffee intake. The primary and secondary outcomes of the study are shown in Table 3 . The mean time to first flatus was shorter in the coffee group than in the control group (29.7±4.9 vs 41.6±10.9 hours; P <.001). In addition, the time to first defecation was significantly shorter in the coffee group (42.0±6.8 vs 59.8±14.6 hours; P <.001), as was the time until patients could tolerate food (3.5±1.2 vs 4.8±1.6 days; P <.001).

| Outcome | Control group (n=56) | Coffee group (n=58) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean time of first flatus, hr a | 41.6±10.9 | 29.7±4.9 | <.001 |

| Mean time of first bowel movement, hr a | 47.5±11.7 | 35.6±5.4 | <.001 |

| Mean time of first defecation, hr a | 59.8±14.6 | 42.0±6.8 | <.001 |

| Additional analgesic, n (%) | 10 (17.9) | 2 (3.4) | .01 |

| Additional antiemetic, n (%) | 9 (16.1) | 2 (3.4) | .02 |

| Ileus symptoms, n (%) | 29 (51.8) | 8 (13.8) | <.001 |

| Mild | 17 (30.4) | 6 (10.3) | .01 |

| Moderate | 9 (16.1) | 2 (3.4) | .02 |

| Severe | 3 (5.4) | — | .11 |

| Time to tolerate diet, d a | 4.8±1.6 | 3.5±1.2 | <.001 |

| Length of hospital stay, d a | 7.4±2.9 | 6.1±1.1 | .003 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree