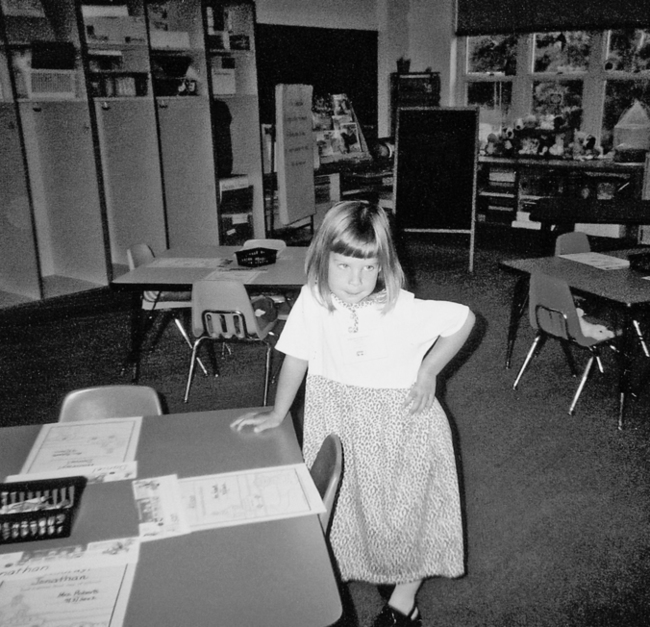

4 After studying this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following: • Identify the federal laws that govern the provision of educational services to children with disabilities. • Explain the formation and function of an individual educational program team. • Explain the process involved in an individual educational program. • Compare and contrast the roles of the occupational therapist and the occupational therapy assistant in the school setting. • Distinguish between the medical and educational models for occupational therapy service delivery. • Describe the techniques for working with teachers and parents in schools. • Differentiate between direct, monitoring, and consultation levels of occupational therapy service delivery. One third to one half of occupational therapy (OT) practitioners work with children; public school systems are the second largest employers.4 Despite these statistics, OT practitioners in public schools often find that they work alone, with a limited support network. This is especially true in rural areas, where one practitioner may provide therapy services to several small school districts or a cooperative educational service area. Being a member of an educational team requires that practitioners broaden their focus on the ways children function in their families, communities, and schools. This mode of thinking contrasts with the traditional medical model of “evaluate and treat,” with its focus on the disabilities or limitations of children.7 As part of a multidisciplinary educational team, OT practitioners working in school systems interact with a variety of people. They must therefore possess specialized technical skills and have knowledge of the educational system, current special education laws, and regulations.3,8 OT practitioners must apply their knowledge and intervention skills in the context of a school setting while communicating effectively with parents* and educators. Occupational therapists working in the public school setting collaborate with teachers and special educators. They work with the student in the classroom whenever possible. Sometimes taking the student to a separate room might be the optimal learning situation for the student (Figure 4-1). OT practitioners develop strategies to facilitate educational goals. Strategies and suggestions may be provided to the teacher to better enhance the student’s learning. Pediatric OT services are mandated by law.4 Box 4-1 summarizes the laws that have an impact on OT services in public school systems. Education is an important occupation of children. As such, OT clinicians working in school systems have the opportunity to directly impact the child’s occupation. They are afforded the luxury of seeing the results of their interventions daily within the context for which it is intended. Their role is to improve the child’s ability to function within that environment; they must become skillful in advocating the needs of the children within the contexts of the setting and the laws. In 1975, the U.S. Congress passed the Education of the Handicapped Act (EHA) (Public Law 94-142) requiring schools to provide free appropriate public education (FAPE) to all children from 5 to 21 years of age.5,8,9 Children with special needs have the right to have their educational programs geared toward their unique needs, regardless of the nature, extent, or severity of their disabilities. In 1986, the law was amended so that public schools could be responsible for providing educational services to children at 3 years of age. The right to be educated in the LRE allows a student who has special needs to be educated in a regular classroom whenever possible.4,9 He or she is entitled to interact with peers who do not have disabilities. Before this law was enacted, students with disabilities were placed in special schools with other students who had disabilities, or they were placed in self-contained classrooms in a separate school building with no opportunity to interact with typically developing peers. The LRE guidelines provided the impetus for the development of mainstreaming and inclusion models (i.e., models in which children with disabilities are able to spend time in regular classrooms). School personnel determine whether a student who has a disability can receive an appropriate education in a regular classroom with the aid of support services and necessary modifications. The team considers whether the child can benefit from any time in a regular classroom. The spirit of the EHA requires that schools provide an entire continuum of services to those students with special needs.2,6,9 For some students, this may mean placement in a regular classroom that has been modified to meet their needs (e.g., one that has been equipped with positioning devices). For other students, it may mean placement in a regular classroom that allows them to go to a resource room for assistance from a special education or resource teacher. Some students need specialized instruction from a special education teacher, and they spend most of the day in the self-contained classroom but are integrated into a regular classroom for certain classes or activities. Students who have difficulty transitioning from one area to another can benefit from reverse mainstreaming, where the regular education students come into the special education classroom during certain courses. According to the EHA, schools are required to provide special, or related, services as necessary for the student to benefit from the educational program. These services include transportation, physical therapy (PT), OT, speech therapy (ST), assistive technology services, psychological services, school health services, social work services, and parent counseling and training.5,9 Except for ST, these services are available only to a student classified as a special education student. ST is a “stand-alone” service, which means that a student who does not receive special education services may receive speech therapy. The educational rights of children with disabilities are protected by two additional federal laws: Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act (1973) and the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA)(1990).2,9 Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act stipulates that any recipient of federal aid (including a school) cannot discriminate when offering services to people with disabilities. The ADA prohibits discriminatory practices in areas related to employment, transportation, accessibility, and telecommunications. A student with a disability who is not eligible for special education services but requires reasonable accommodation in his or her regular educational program may be eligible to receive related services under these laws. To be eligible, the student must have a condition that “substantially limits one or more major life activities,” with learning being a major life activity.2 1. He must complete 50% of his work in class; other work will be sent home. 2. He will have extra class time to complete work whenever possible. 3. Classroom supplies will be readily available and placed in front of him before a task begins. 4. OT will be provided to increase strength and endurance for academic functions. 5. A peer or an adult will accompany him when he leaves the classroom. The EHA was renamed the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) in 1990; it was revised in 1997 and is now known as IDEA-R. This act encourages OT practitioners to work with children in their classroom environment (inclusion) and provide support to the regular education teacher (integration). It also encourages schools to allow students with disabilities to work toward meeting the same educational standards as their peers. IDEA-R changed the process for the identification, evaluation, and implementation of IEPs. Table 4-1 contains a comparison of the IDEA and the IDEA-R. For example, the occupational therapist and the occupational therapy assistant (OTA) can assist in the evaluation of the student to determine the need for the acquisition of a device that allows the child to remain in a regular classroom. The practitioner may consult with others on positioning, train team members, and consult with others on strategies to increase the likelihood of success in the classroom. The role of the occupational therapist under IDEA-R is to assist children with special needs so that they can participate in educational activities. TABLE 4-1 The No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) was enacted in 2001 in order to improve teaching standards and the student’s learning results. NCLB supports the use of scientifically based practices by professionals working in the educational setting. Therefore, educators and OT practitioners are required to consider research when selecting instructional or interventional practices. Schools must report adequate yearly progress through a single accountability system that applies the same standards to all students. These standards are based on each state’s academic achievement standards. Teacher quality and paraprofessional competencies are also parts of this Act, yet it does not specifically address the competencies of related services such as OT.10 OT practitioners need to collaborate and consult with the team to prioritize the student’s needs. Therapy is integrated into the classroom and provides consistent follow-through. Student-centered Individualized Educational Plan (IEP) goals and objectives enhance success in the educational environment (Figure 4-2).10 The IDEA-R outlines several procedural safeguards for children with disabilities and for their parents. These procedures are detailed in the United States Code of Federal Regulations, Title 34, Subtitle B, Chapter III, Part 300. To summarize, the safeguards include notifying parents of all proposed actions, obtaining consent to evaluate, allowing parents to attend IEP team meetings, and providing the right to an independent evaluation and the right to appeal school decisions in front of an impartial hearing officer.9 The IDEA-R requires that school districts inform parents of their rights in a written format. After a referral for OT services is received and parental consent is obtained, an evaluation can be initiated. (Some state and Medicaid conditions require a physician’s order as a prerequisite to initiating these services.) Evaluations measure the student’s abilities at that particular time. Therefore, it is important to consider the viewpoint of everyone involved with the student, including teachers and parents. Knowledge of the student’s strengths and needs may be gained from consultation with the teacher, parent, child, and staff. Standardized tests and clinical observations provide important information. State, local, and school policies may dictate what type of assessment will be used. However, clinicians must consider the child’s needs in choosing an assessment. Observation of the child in the classroom, cafeteria, playground, and bathroom provides information about his or her functional skills.1 Many children are able to perform certain activities in a quiet one-on-one situation but have difficulty generalizing or modulating them in a busy classroom. Students may also perform better when they are not aware that someone is watching or observing. Consultation with the teacher is key in identifying the specific problems and needs of the student. A questionnaire or referral form completed by the teacher is helpful to the team. The occupational therapist is responsible for completing the evaluation (with input from the OTA), interpreting the information, and presenting the report to the IEP team. The skills of the student should be reassessed before different objectives are formulated for a new IEP. Students are re-evaluated as needed or if requested by the parents, teachers, or team members. They must be re-evaluated at least every 3 years. The IEP team determines the student’s eligibility once all evaluations are completed. Eligibility for services in public schools is based on exceptional educational need (EEN). The IEP team must consider all of the information obtained through the evaluations in order to determine whether the disability or condition interferes with the student’s ability to participate in an educational program and whether the student needs related services to benefit from an educational program.5,9 The presence of a disability does not necessarily mean that a student cannot participate in the regular educational program; nor does it mean that the student has an EEN.

Educational system

Practice settings

Federal laws

Education of the handicapped act (public law 94-142)

Least restrictive environment

Related services

Rehabilitation act and americans with disabilities act

Case study

Individuals with disabilities education act

FORMER IDEA

IDEA-R

TEAM NAMES

M-team (multidisciplinary team)

IEP team

REGULAR EDUCATION TEACHERS

Works with students other than those with learning disabilities; not involved with special education students

Participation on IEP team

MEETINGS

Numerous meetings

Two meetings: (1) an M-team meeting to determine eligibility, and (2) a separate IEP and placement meeting to determine services and program

One meeting

Placement meeting

Possible parental involvement

Required parental involvement

REPORTS

M-team summary with minority report; if a member of the team disagrees with the eligibility findings, that member can submit a dissenting report

Single report of IEP team’s determination of eligibility; no minority report

CONSENT

Not required for re-evaluation

Parental consent for re-evaluation

MEDIATION

Not available

Mediation (a voluntary process in which an impartial person helps schools and families reach agreement on issues related to the identification, evaluation, and educational placement of the child and provision of a free, appropriate public education without going through a due process hearing)

SPECIAL NEEDS TERMINOLOGY

Handicapping condition, or handicap

Disability

PARENTS’ RIGHTS

Sent six times

Sent three times

No child left behind act

Rights of parents and children

Evaluation

Eligibility

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree