KEY POINTS

• Ectopic pregnancy is common and can be life threatening.

• Clinical signs and symptoms are nonspecific and are frequently present in healthy pregnancy as well as ectopic pregnancy.

• Serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin levels and ultrasound are used to make early diagnosis.

• Medical or surgical treatment may be used, with similar long-term outcomes in terms of tubal function and future fertility.

BACKGROUND

Definition

An ectopic pregnancy is one in which the fertilized ovum implants at any site other than the endometrial cavity. The fallopian tube is the most common site, accounting for more than 95% of ectopic pregnancies, but other implantation sites include the cervix, abdominal cavity, and ovary (1).

Incidence

The incidence of ectopic pregnancy in the United States has nearly tripled over the past 30 years; whether this is due to increasing recognition because of sensitive diagnostic tools or a true increase is unclear. Currently, ectopic locations are diagnosed in approximately 2% of clinically recognized pregnancies (2). The prevalence of ectopic among women presenting with first-trimester bleeding and/or abdominal pain can be up to 18% (1). Ectopic pregnancy is the most common cause of nonpuerperal maternal mortality and is the leading cause of first-trimester maternal death (2).

Etiology

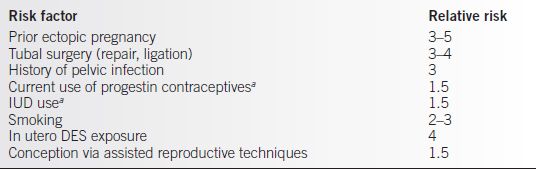

A number of risk factors for ectopic pregnancy have been identified (Table 7-1), including the following conditions (3):

• Salpingitis. Approximately 50% of ectopic pregnancies can be attributed to a history of salpingitis. Salpingitis has been shown to increase a woman’s risk for ectopic pregnancy sevenfold. Chlamydial salpingitis may pose a greater risk than gonorrheal infection.

• Prior ectopic pregnancy. In subsequent pregnancies, there is a 15% to 20% risk of recurrence, in either the same or opposite tube.

• Peritubal adhesions following postabortal or puerperal infections, appendicitis, or endometriosis.

• Tubal surgery, including tubal ligation, tubal reanastomosis, prior surgery for ectopic pregnancy, and tubal reconstruction for fertility.

• Intrauterine device. Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are highly effective at preventing intrauterine pregnancy. Thus, any pregnancy in an IUD user is more likely to be tubal.

• Progestin-only contraceptives. Users of progestin-only oral contraceptives as well as injectable progestins are at increased risk of ectopic pregnancy if pregnancy occurs, possibly because of altered tubal motility.

• History of infertility. Infertile couples have an increased proportion of ectopic pregnancies compared to the total number of pregnancies, regardless of the etiology of the infertility.

• Assisted reproductive techniques (ART):

• Women who have conceived via ART are at increased risk of ectopic pregnancy, regardless of the etiology of their infertility. Approximately 2% of pregnancies occurring as a result of in vitro fertilization, gamete intrafallopian tube transfer (GIFT), gonadotropin-stimulated superovulation, and other methods of assisted reproduction result in ectopic pregnancies (4).

• Heterotopic pregnancy (simultaneous ectopic and intrauterine pregnancies) occurs at a much higher rate in women treated with assisted reproductive technologies. Up to 2% of ectopic pregnancies in this population are heterotopic.

• Diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is more challenging in women receiving reproductive assistance. Women treated with assisted reproductive technologies are more likely to have abdominal pain and spotting early in pregnancy. Even when confronted by a probable ectopic pregnancy, both patients and clinicians are reluctant to interfere with technologically conceived pregnancies, which may result in delay in treatment.

• Developmental abnormalities of the tube, such as diverticula, accessory ostia, and hypoplasia. Women who have been exposed to diethylstilbestrol (DES) have a four to five times greater risk of ectopic pregnancy.

• Increased maternal age.

Table 7-1 Risk Factors and Relative Risk for Ectopic Pregnancy

aTotal number pregnancies decreased, but percentage of ectopic pregnancies increased. IUD, intrauterine device; DES, diethylstilbestrol.

Pathogenesis

• In tubal pregnancies, the fertilized ovum implants in the epithelium of the tube. The trophoblast invades the tubal muscularis and the maternal blood supply, resulting in bleeding and weakening of the tubal wall. Eventually, the pregnancy either extrudes out the fimbriated end of the tube (tubal abortion) or ruptures the wall of the tube. Either of these situations can cause intra-abdominal bleeding.

• Approximately 80% of tubal pregnancies implant in the ampullary portion of the tube, and 5% implant more distally on the fimbriae.

• Isthmic pregnancies, accounting for approximately 13% of ectopic pregnancies, rupture earlier than do ampullary pregnancies and may result in secondary broad ligament implantation.

• Interstitial pregnancies, although only 2% of ectopics, result in the greatest morbidity because they can grow large and can mimic an intrauterine pregnancy. When these pregnancies rupture, severe hemorrhage may ensue.

DIAGNOSIS

• Ectopic pregnancy should be suspected any time a woman presents with bleeding and/or pain in early pregnancy. While abnormal intrauterine pregnancy is more common than is ectopic pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy is more likely to be life threatening; therefore, it is critical to consider the diagnosis.

• The diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is not always obvious; initial diagnoses are often incorrect. Women may present with catastrophic intra-abdominal hemorrhage and shock; however, more frequently, they will have ill-defined abdominal pain and minimal vaginal bleeding.

• It is important to carefully evaluate all women of reproductive age with abdominal pain. Early diagnosis before rupture decreases morbidity and allows wider treatment options. More than half of women presenting with life-threatening intra-abdominal bleeding have had at least one visit to a health care provider before rupture.

Clinical Manifestations

• Signs and symptoms with a less catastrophic presentation:

• Abdominal pain is present in more than 95% of women with ectopic pregnancy. The pain often begins as intermittent, colicky discomfort in one lower quadrant, progressing to more constant, severe pain that generalizes throughout the lower abdomen. The degree of pain may be less than expected, even with a significant hemoperitoneum. Shoulder pain is present in 15% of women with a ruptured ectopic pregnancy as a result of blood irritating the diaphragm.

• Delayed menses is reported by 90% of women with ectopic pregnancy, varying from a few days to several weeks.

• Vaginal bleeding, often as spotting, is present in 80% to 90% of women in whom ectopic pregnancy is ultimately diagnosed. However, bleeding is present in about half of all pregnancies, even those with normal outcome. The abnormal bleeding results from low hormonal levels with resulting slough of the endometrium. Bleeding ranges from scant spotting to menstrual-like flow. Some women report passage of tissue, representing decidualized endometrium.

• Physical examination reveals abdominal tenderness, adnexal tenderness, especially unilateral, and cervical motion tenderness. Up to 10% of women present with intra-abdominal hemorrhage, in which case diffuse abdominal tenderness and rigidity, rebound tenderness, and hypovolemic shock may be present.

Abdominal tenderness is found in 80% to 90% of women with ectopic pregnancies varying from mild to severe tenderness, guarding, and rebound tenderness.

Abdominal tenderness is found in 80% to 90% of women with ectopic pregnancies varying from mild to severe tenderness, guarding, and rebound tenderness.

Adnexal tenderness on pelvic exam is present in nearly all women with ectopic pregnancies, and it may be associated with cervical motion tenderness.

Adnexal tenderness on pelvic exam is present in nearly all women with ectopic pregnancies, and it may be associated with cervical motion tenderness.

Adnexal mass or cul-de-sac mass may be palpable in 50% of women with ectopic pregnancy; however, it is contralateral to the pregnancy nearly half the time and is often a corpus luteum cyst rather than the gestation itself.

Adnexal mass or cul-de-sac mass may be palpable in 50% of women with ectopic pregnancy; however, it is contralateral to the pregnancy nearly half the time and is often a corpus luteum cyst rather than the gestation itself.

Uterine enlargement, often less than expected relative to the last menstrual period, is present in 25% and does not rule out ectopic pregnancy.

Uterine enlargement, often less than expected relative to the last menstrual period, is present in 25% and does not rule out ectopic pregnancy.

• Women with catastrophic presentation. Women with hemoperitoneum as a result of ruptured ectopic pregnancy will present with an acute abdomen and shock. Often there is a history of vague abdominal pain followed by sudden and worsening acute pain beginning in the lower quadrants and extending to the entire abdomen. Pelvic exam may reveal a doughy mass in the cul-de-sac caused by clotted blood. Assessment of the uterus and adnexa is usually impossible because of abdominal distention and rigidity.

Differential Diagnosis

• Other pregnancy-related conditions. Threatened, incomplete, or complete spontaneous abortion, septic abortion, and hydatidiform mole may be confused with ectopic gestations. A normal early intrauterine pregnancy with a bleeding corpus luteum cyst must also be considered. The combination of clinical findings, quantitative human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG), and ultrasound can usually help distinguish these conditions.

• Non–pregnancy-related conditions. Salpingitis, appendicitis, adnexal torsion, ruptured corpus luteum in the absence of pregnancy, and urinary tract disorders such as infection and stones must be considered. Generally, negative results of a sensitive urine or serum pregnancy test can eliminate ectopic pregnancy when these diagnoses are being considered.

• Intra-abdominal hemorrhage secondary to ruptured spleen or liver may present a diagnostic challenge in the pregnant patient; however, because patients presenting in this manner need urgent surgery, such difficulties in diagnosis may not be problematic.

EVALUATION

Laboratory Tests

• Pregnancy testing. Testing for β-hCG levels is of great value in evaluating a woman with suspected ectopic pregnancy, as virtually all ectopic pregnancies will be associated with detectable levels of β-hCG in blood or urine. These tests should be available in all facilities providing health care to women of reproductive age.

• Current urine pregnancy tests are sensitive to 20 to 25 IU β-hCG, which is the level excreted in the urine at or before the 1st day of expected menses. β-hCG is detectable in maternal serum within 8 days of ovulation. The β-hCG level rises rapidly, initially doubling in 1 to 1.5 days. By approximately 5 weeks’ gestation menstrual age (3 weeks postconception), β-hCG will normally double about every 48 hours. However, a 53% increase in β-hCG value in 48 hours is considered the lower limit of normal and defines a potentially viable intrauterine pregnancy (5).

• Ectopic pregnancies produce less β-hCG than do normal intrauterine pregnancies at the same gestational age because of a smaller volume of functional trophoblasts. Consequently, the rate of β-hCG rise is slower than in normal intrauterine pregnancies. The failure of serial β-hCG levels to rise at the proper rate can be used to distinguish ectopic pregnancy from normal pregnancy, but a normally rising β-hCG concentration does not exclude ectopic pregnancy (5).

• If the exact date of conception is known, a single β-hCG level can predict normal versus abnormal placentation; however, an error of even 48 hours in the date of conception can obviously lead to confusing results. Therefore, single β-hCG levels alone are of limited clinical usefulness.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree