Bailer UF, Kaye WH: A review of neuropeptide and neuroendocrine dysregulation in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Curr Drug Target CNS Neurol Disord 2003;2:53 [PMID: 12769812].

Bulik CM, Slof-Op’t Landt MC, van Furth EF, Sullivan PF: The genetics of anorexia nervosa. Annu Rev Nutr 2007a;27:263–275.

Campbell IC, Mill J, Uher R, Schmidt U: Eating disorders, gene-environment interaction, and epigentics. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2011;35:784–793 [PMID: 20888360].

Disanto G et al: Season of birth and anorexia nervosa. Brit J Psych 2011;198(5):404–407 [PMID: 21415047].

Germain N et al: Ghrelin/obestatin ratio in two populations with low bodyweight: constitutional thinness and anorexia nervosa. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009;34(3):413–419 [PMID: 18995969].

Mercader JM et al: Association of NTRK3 and its interaction with NGF suggest an altered cross-regulation of the neurotrophin signaling pathway in eating disorders. Hum Mol Genet 2008;17(9):1234–1244.

Procopio M, Marriott P: Intrauterine hormonal environment and risk of developing anorexia nervosa. Arch Gen Psych 2007; 64(12):1402 [PMID: 18056548].

Strober M et al: Males with anorexia nervosa: a controlled study of eating disorders in first-degree relatives. Int J Eat Disord 2001;29:263 [PMID: 11262504].

Warren MP: Endocrine manifestations of eating disorders. J Clinical Endocrin Metabolism 2011;96(2):333 [PMID: 21159848].

INCIDENCE

AN is the third most common chronic illness of adolescent girls in the United States. The incidence has been increasing steadily in the United States since the 1930s. Although ascertaining exact incidence is difficult, most studies show that 1%–2% of teenagers develop AN and 2%–4% develop BN. Adolescents outnumber adults 5 to 1, although the number of adults with eating disorders is rising. Incidence is also increasing among younger children. Prepubertal patients often have associated psychiatric diagnoses. Males comprise about 10% of patients with EDs, though this prevalence appears to be increasing as well, associated with the increased media emphasis on muscular, chiseled appearance as the male ideal.

Literature on preadolescents with EDs suggests that patients younger than 13 years are more likely to be male compared to teenagers and more likely to have EDNOS. Younger patients are less likely to engage in behaviors characteristic of BN. They present with more rapid weight loss and lower percentile body weight than adolescents.

Teenagers’ self-reported prevalence of ED behavior is much higher than the official incidence of AN or BN. In the most recent Youth Risk Behavior Survey of US teenagers (2011), 61% of females and 32% of males had attempted to lose weight during the preceding 30 days. Twelve percent had fasted for more than 24 hours to lose weight, and 5% had used medications to lose weight (5.9% of girls and 4.2% of boys). Self-induced vomiting or laxative use was reported by 6% of females and 2.5% of males. Forty-six percent of females and 30% of males reported at least one binge episode during their lifetime. Although the number of youth with full-spectrum eating disorders is low, it is alarming that so many youth experiment with unhealthy weight control habits. These behaviors may be precursors to the development of eating disorders, and clinicians should explore these practices with all adolescent patients.

Eaton DK et al: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance: United States 2011. MMWR Surveill Summ June 8 2012;61(SS-4) [PMID: 22673000]. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss6104.pdf.

Halmi KA: Anorexia nervosa: an increasing problem in children and adolescents. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2009;11(1):100–103 [PMID: 19432392].

Peebles R et al: How do children with eating disorders differ from adolescents with eating disorders at initial evaluation? J Adolesc Health 2006;39:800 [PMID: 17116508].

PREDISPOSING FACTORS & CLINICAL PROFILES

Children involved in gymnastics, figure skating, and ballet—activities that emphasize thin bodies—are at higher risk for AN than are children in sports that do not emphasize body image. Adolescents who believe that being thin represents the ideal frame for a female, those who are dissatisfied with their bodies, and those with a history of dieting are at increased risk for eating disorders. Sudden changes in dietary habits, such as becoming vegetarian, may be a first sign of anorexia, especially if the change is abrupt and without good reason.

The typical bulimic patient tends to be impulsive and to engage in risk-taking behavior such as alcohol use, drug use, and sexual experimentation. Bulimic patients are often an appropriate weight for height or slightly overweight. They have average academic performance. Youth with diabetes have an increased risk of BN. In males, wrestling predisposes to BN, and homosexual orientation is associated with binge eating.

Shaw H et al: Body image and eating disturbances across ethnic groups: more similarities than differences. Psychol Addict Behav 2004;18:8 [PMID: 15008651].

Striegel-Moore RH, Bulik CM: Risk factors for eating disorders. Am Psychol 2007;62:181 [PMID: 17469897].

ANOREXIA NERVOSA

Table 6–1 lists the diagnostic criteria for AN, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V). The new DSM-V contains significant changes to the diagnosis of AN, including the elimination of amenorrhea as a criterion as well as specific weight criteria, which used to be 85% of expected weight based on 50th percentile body mass index (BMI). These changes will significantly increase the number of youth receiving AN as a diagnosis.

There are two forms of AN. In the restricting type, patients do not regularly engage in binge eating or purging. In the binge-purge type, AN is combined with binge eating or purging behavior, or both. Distinguishing between the two is important as they carry different implications for prognosis and treatment. Although patients may not demonstrate all features of AN, they may still exhibit the deleterious symptoms associated with AN.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Clinicians should recognize the early symptoms and signs of AN because early intervention may prevent the full-blown syndrome from developing. Patients may show some of the behaviors and psychology of AN, such as reduction in dietary fat and intense concern with body image, even before weight loss or amenorrhea occurs.

Table 6–1. Diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa.

1. Restriction of energy intake relative to requirements, leading to a significantly low body weight in the context of age, sex, development trajectory, and physical health. Significantly low weight is defined as a weight that is less than minimally normal or, for children and adolescents, less than that minimally expected. 2. Intense fear of gaining weight or of becoming fat, or persistent behavior that interferes with weight gain, even though at a significantly low weight. 3. Disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or persistent lack of recognition of the seriousness of the current low body weight. |

Specify whether: Restricting type: During the last 3 months, the individual has not engaged in recurrent episodes of binge eating or purging behavior (ie, self-induced vomiting or the misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas). This subtype describes presentations in which weight loss is accomplished primarily through dieting, fasting, and/or excessive exercise. Binge-eating/purging type: During the last 3 months, the individual has engaged in recurrent episodes of binge eating or purging behavior (ie, self-induced vomiting or the misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas). |

Reprinted, with permission, from American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed, Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Making the diagnosis of AN can be challenging because adolescents may try to conceal their illness. Assessing the patient’s body image is essential to determining the diagnosis. Table 6–2 lists screening questions that help tease out a teenager’s perceptions of body image. Other diagnostic screening tools (eg, Eating Disorders Inventory) assess a range of eating and dieting behaviors. Parental observations are critical in determining whether a patient has expressed dissatisfaction over body habitus and which weight loss techniques the child has used. If the teenager is unwilling to share his or her concerns about body image, the clinician may find clues to the diagnosis by carefully considering other presenting symptoms or signs. Weight loss from a baseline of normal body weight is an obvious red flag for the presence of an eating disorder. Additionally, AN should be considered in any girl with secondary amenorrhea who has lost weight.

Table 6–2. Screening questions to help diagnose anorexia and bulimia nervosa.

How do you feel about your body? Are there parts of your body you might change? When you look at yourself in the mirror, do you see yourself as overweight, underweight, or satisfactory? If overweight, how much do you want to weigh? If your weight is satisfactory, has there been a time when you were worried about being overweight? If overweight (underweight), what would you change? Have you ever been on a diet? What have you done to help yourself lose weight? Do you count calories or fat grams? Do you keep your intake to a certain number of calories? Have you ever used nutritional supplements, diet pills, or laxatives to help you lose weight? Have you ever made yourself vomit to get rid of food or lose weight? |

Physical symptoms and signs are usually secondary to weight loss and proportional to the degree of malnutrition. The body effectively goes into hibernation, becoming functionally hypothyroid (euthyroid sick) to save energy. Body temperature decreases, and patients report being cold. Bradycardia develops, especially in the supine position. Dizziness, light-headedness, and syncope may occur as a result of orthostasis and hypotension secondary to impaired cardiac function. Left ventricular mass is decreased (as is the mass of all striated muscle), stroke volume is compromised, and peripheral resistance is increased, contributing to left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Patients can develop prolonged QTc syndrome and increased QT dispersion (irregular QT intervals), putting them at risk for cardiac arrhythmias. Peripheral circulation is reduced. Hands and feet may be blue and cool. Hair thins, nails become brittle, and skin becomes dry. Lanugo develops as a primitive response to starvation. The gastrointestinal (GI) tract may be affected; inability to take in normal quantities of food, early satiety, and gastroesophageal reflux can develop as the body adapts to reduced intake. The normal gastrocolic reflex may be lost due to lack of stimulation by food, causing bloating and constipation. Delayed gastric emptying may be present in restricting type and purging type AN. Nutritional rehabilitation improves gastric emptying and dyspeptic symptoms in AN restricting type, but not in those who vomit. Neurologically, patients may experience decreased cognition, inability to concentrate, increased irritability, and depression, which may be related to structural brain changes and decreased cerebral blood flow.

Nutritional assessment is vital. Often, patients eliminate fat from their diets and may eat as few as 100–200 kcal/d. A gown-only weight after urination is the most accurate way to assess weight. Patients tend to wear bulky clothes and may hide weights in their pockets or drink excessive fluid (water-loading) to trick the practitioner. Assessing BMI is the standard approach to interpreting the degree of malnutrition. BMI below the 25th percentile indicates risk for malnutrition, and below 5th percentile indicates significant malnutrition. Median body weight (MBW) should be calculated as it serves both as the denominator in determining what percent weight an individual is, as well as to provide a general goal weight during recovery. MBW for height is calculated by using the 50th percentile of BMI for age.

A combination of malnutrition and stress causes hypothalamic hypogonadism. The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis shuts down as the body struggles to survive, directing finite energy resources to vital functions. This may be mediated by the effect of low serum leptin levels on the hypothalamic-pituitary axis. Pubertal development and skeletal growth may be interrupted, and adolescents may experience decreased libido.

Amenorrhea will continue to be an important clinical sign that the body is malnourished. Amenorrhea occurs for two reasons. The hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis shuts down under stress, causing hypothalamic amenorrhea. In addition, adipose tissue is needed to convert estrogen to its activated form. When weight loss is significant, there is not enough substrate to activate estrogen. Resumption of menses occurs only when both body weight and body fat increase. Approximately, 73% of postmenarchal girls resume menstruating if they reach 90% of MBW. An adolescent female needs about 17% body fat to restart menses and 22% body fat to initiate menses if she has primary amenorrhea. Some evidence suggests that target weight gain for return of menses is approximately 1 kg higher than the weight at which menses ceased.

B. Laboratory Findings

All organ systems may suffer some degree of damage in the anorexic patient, related both to severity and duration of illness (Table 6–3). Initial screening should include complete blood count with differential; serum levels of electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, phosphorus, calcium, magnesium, and thyroid-stimulating hormone; liver function tests; and urinalysis. Increase in lipids, likely due to abnormal liver function, is seen in 18% of those with AN, with subsequent return to normal once weight is restored. An electrocardiogram (ECG) should be performed, because significant electrocardiographic abnormalities may be present, most importantly prolonged QTc syndrome. Bone densitometry should be done if illness persists for 6 months, as patients begin to accumulate risk for osteoporosis.

Table 6–3. Laboratory findings: anorexia nervosa.

Increased blood urea nitrogen and creatinine secondary to renal insufficiency Decreased white blood cells, platelets, and less commonly red blood cells and hematocrit secondary to bone marrow suppression or fat atrophy of the bone marrow Increased AST and ALT secondary to malnutrition Increased cholesterol, thought to be related to altered fatty acid metabolism Decreased alkaline phosphatase secondary to zinc deficiency Low- to low-normal thyroid-stimulating hormone and thyroxine Decreased follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, estradiol, and testosterone secondary to shutdown of hypothalamic pituitary-gonadal axis Abnormal electrolytes related to hydration status Decreased phosphorus Decreased insulin-like growth factor Increased cortisol Decreased urine specific gravity in cases of intentional water intoxication |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

If the diagnosis is unclear (ie, the patient has lost a significant amount of weight but does not have typical body image distortion or fat phobia), the clinician must consider the differential diagnosis for weight loss in adolescents. This includes inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, hyperthyroidism, malignancy, depression, and chronic infectious disease such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Less common diagnoses include adrenal insufficiency and malabsorption syndromes such as celiac disease. The history and physical examination should direct specific laboratory and radiologic evaluation.

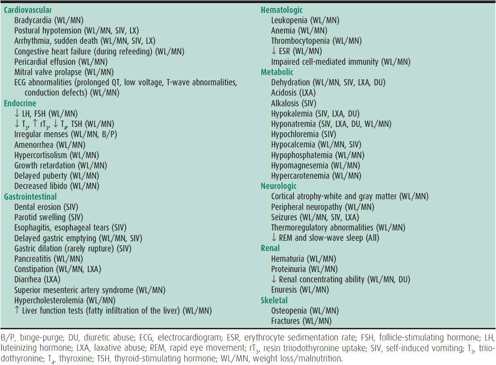

Complications (Table 6–4)

Complications (Table 6–4)

A. Short-Term Complications

1. Early satiety— Patients may have difficulty tolerating even modest quantities of food when intake increases; this usually resolves after the patients adjust to larger meals. Gastric emptying is poor. Pancreatic and biliary secretion is diminished.

2. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome— As patients become malnourished, the fat pad between the superior mesenteric artery and the duodenum shrinks and compression of the transverse duodenum may cause obstruction and vomiting, especially with solid foods. The upper GI series shows to-and-fro movement of barium in the descending and transverse duodenum proximal to the obstruction. Treatment involves a liquid diet or nasoduodenal feedings until restoration of the fat pad has occurred, coincident with weight gain.

Table 6–4. Complications of anorexia and bulimia nervosa, by mechanism.

3. Constipation— Patients may be very constipated. Two mechanisms contribute—loss of the gastrocolic reflex and loss of colonic muscle tone. Typically stool softeners are not effective because the colon has decreased peristaltic amplitude. Agents that induce peristalsis, such as bisacodyl, as well as osmotic agents, such as polyethylene glycol-electrolyte solution (MiraLax), are helpful. Constipation can persist for up to 6–8 weeks after refeeding. Occasionally enemas are required.

4. Refeeding syndrome— This syndrome is described in the Treatment section.

5. Pericardial effusion— The degree of malnutrition correlates with increasing prevalence of pericardial effusion. One study demonstrated that 22% of those with AN had silent pericardial effusions, with 88% of effusions resolving after weight restoration.

B. Long-Term Complications

1. Osteoporosis—Approximately 50% of females with AN have reduced bone mass at one or more sites. The lumbar spine has the most rapid turnover and is the area likely to be affected first. Teenagers are particularly at risk as they accrue 40% of their bone mineral during adolescence. Low body weight is most predictive of bone loss. The causes of osteopenia and osteoporosis are multiple. Estrogen and testosterone are essential to potentiate bone development. Bone minerals begin to resorb without estrogen. Elevated cortisol levels and decreased insulin-like growth factor-1 also contribute to bone resorption. Amenorrhea is highly correlated with osteoporosis. Studies show that as few as 6 months of amenorrhea is associated with osteopenia or osteoporosis. Males may also develop osteoporosis due to decreased testosterone and elevated cortisol.

Until recently, the only proven treatment for bone loss in girls with AN has been regaining sufficient weight and body fat to restart the menstrual cycle. Studies did not support use of hormone replacement therapy delivered orally to improve bone recovery; however, a recent randomized controlled trial demonstrated that physiologic doses of estrogen, delivered transdermally, over 18 months did improve bone density. Clinicians may consider transdermal estrogen treatment if patients are recalcitrant to intervention and do not restore weight in a timely manner. Bisphosphonates, used to treat postmenopausal osteoporosis, are currently being studied in adolescents. Two small randomized controlled trials have shown small positive effects on bone density with alendronate and risedronate, although clinical effectiveness has not yet been determined. Newer treatments with possible effectiveness, including recombinant insulin-like growth factor-1 injection and dehydroepiandrosterone, are under investigation.

2. Brain changes—As malnutrition becomes pronounced, brain tissue—both white and gray matter—is lost, with a compensatory increase in cerebrospinal fluid in the sulci and ventricles. Follow-up studies of weight-recovered anorexic patients show a persistent loss of gray matter, although white matter returns to normal. Functionally, there does not seem to be a direct relationship between cognition and brain tissue loss, although studies have shown a decrease in cognitive ability and decreased cerebral blood flow in very malnourished patients. Making patients and family aware that brain tissue can be lost may improve their perception of the seriousness of this disorder. There is a burgeoning literature on functional brain imaging. Neurochemical changes, including changes related to serotonin and dopamine systems, occur as a result of starvation and lead to altered metabolism in frontal, cingulate, temporal, and parietal regions (for a detailed review, see Kaye et al, 2009).

3. Effects on future children—This area has just recently been studied. Findings suggest that there may be feeding issues for infants who are born to mothers who have a history of either AN or BN. Infants born to mothers with a history of AN have more feeding difficulties at 0 and 6 months and tend to be lower weight (30th percentile on average). Infants born to mothers with current or past BN are more likely to be overweight and have faster growth rates than controls. Pediatricians should ascertain an eating disorder history from mothers of patients who are having feeding issues.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree