Early Pregnancy Loss

T. Flint Porter

D. Ware Branch

James R. Scott

Miscarriage, also termed spontaneous abortion, is most commonly used to describe first-trimester loss, although it has also been used to describe loss before 20 weeks. These arbitrary time limits have become less useful with advances in developmental biology and diagnostic sonography. Early pregnancy loss is more precisely defined as preembryonic (conception through the first 5 weeks of pregnancy from the first day of the last menstrual period), embryonic (6 to 9 weeks gestation), or fetal (10 weeks until delivery).

Epidemiology

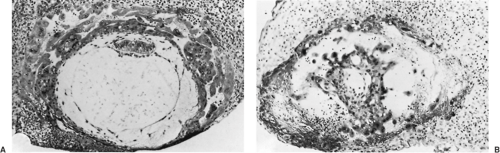

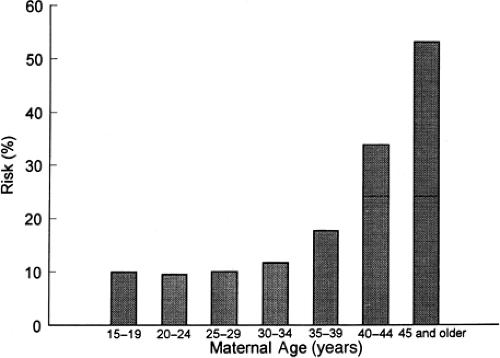

Miscarriage is the most common complication of pregnancy, occurring in at least 15% of clinically recognized pregnancies. Histologically defective ova found in hysterectomy specimens (Fig. 4.1) and data on early pregnancies detected with sensitive β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) assays indicate that the rate is two to three times higher in early, unrecognized pregnancies. Miscarriage rates also vary with maternal age, ranging from 12% in women younger than 20 years of age to over 50% in women older than 45 years of age (Fig. 4.2). The likelihood of miscarriage is heavily dependent on past obstetric history, being higher among women with prior miscarriages and lower among women whose past pregnancy or pregnancies ended in live births.

Embryology

Successful pregnancy is dependent on integration of several complex processes involving genetic, hormonal, immunologic, and cellular events, all working together in perfect order to achieve fertilization, implantation, and embryonic development. It is not surprising that early pregnancy loss can occur because of a number of embryonic and parental factors.

Embryonic Factors

Most single, sporadic miscarriages are caused by nonrepetitive intrinsic defects in the developing conceptus, such as abnormal germ cells, chromosomal abnormalities in the conceptus, defective implantation, defects in the developing placenta or embryo, accidental injuries to the fetus, and probably other causes as yet unrecognized. Fifty percent of women presenting with spotting or cramping already have a nonviable conceptus by sonogram, and many of these embryos are morphologically abnormal. About one third of abortus specimens from losses occurring before 9 weeks gestation are anembryonic. Some cases of empty gestational sacs or “blighted ova” actually represent pregnancy failures with subsequent embryonic resorption. The high proportion of abnormal aborted concepti is apparently the result of a selective process that eliminates about 95% of morphologic and cytogenetic errors.

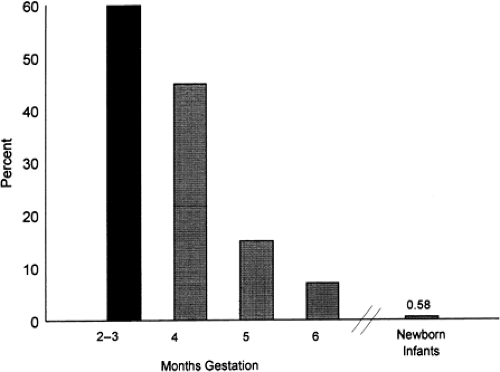

The frequency of chromosomally abnormal spontaneously aborted products of conception in the first trimester is approximately 60%, decreasing to 7% by the end of the 24th week (Fig. 4.3). The rate of genetic abnormalities is higher in anembryonic miscarriages. Autosomal trisomies are the most common (51.9%), arising de novo as a result of meiotic nondisjunction during gametogenesis in parents with normal karyotypes. The relative frequency of each type of trisomy differs considerably. Trisomy 16, which accounts for about one third of all trisomic abortions, has not been reported in live-born infants and is therefore uniformly lethal. Trisomy 22 and 21 follow in frequency. The next most common chromosomal abnormalities, in decreasing order, are monosomy 45,X (the single most common karyotypic abnormality), triploidy, tetraploidy, translocations, and mosaicism.

Media publicity tends to give the impression that a variety of agents such as infections, video display terminals, cigarette smoking, coffee, ethanol, chemical agents, and drugs markedly increase the risk of miscarriage. In reality, there is little credible supportive evidence.

Pathology

Most miscarriages occur within a few weeks after the death of the embryo or rudimentary analog. Initially, there is hemorrhage into the decidua basalis, with necrosis and inflammation in the region of implantation. The gestational sac is partially or entirely detached. Subsequent uterine contractions and dilation of the cervix eventually result in expulsion of most or all of the products of conception. When the sac is opened, fluid is often found surrounding a small macerated embryo, although no visible embryo may be present. Histologically, hydropic degeneration of the placental villi caused by retention of tissue fluid is common.

Clinical Features and Treatment

An unrecognized pregnancy should always be considered in any woman of reproductive age with abnormal bleeding or pain. Likewise, a patient with known pregnancy should notify her physician promptly about vaginal bleeding or uterine cramps. Since management depends on several clinical factors, it is useful to consider miscarriage under the following subgroups.

Threatened Miscarriage

Any bloody vaginal discharge or uterine bleeding that occurs during the first half of pregnancy has traditionally been assumed to be a threatened miscarriage. Spotting or bleeding during the early months of gestation occurs quite commonly, in as many as 25% of pregnant women. Bleeding is typically scanty, varying from a brownish discharge to bright red bleeding. It may occur repeatedly over the course of many days and usually precedes uterine cramping or low backache. On pelvic examination, the cervix is closed and uneffaced, and no tissue has passed. The differential diagnosis includes ectopic pregnancy, molar pregnancy, vaginal ulcerations, cervicitis with bleeding, cervical erosions, polyps, and carcinoma.

Women presenting with threatened miscarriage should receive an ultrasound examination to determine location, viability, and gestational age. Accurate knowledge of gestational age is necessary for proper interpretation, as a sonographically empty uterus may imply an abnormal intrauterine or ectopic pregnancy when it actually represents a normal early gestation. Serial testing of β-hCG measurements is a useful adjunct if the diagnosis remains uncertain, along with a follow-up sonogram a few days later.

A viable conceptus can be detected with modern ultrasound as early as 5.5 weeks gestation. It is possible to visualize the yolk sac and gestational sac starting at 5 to 6 weeks by using transvaginal ultrasound, with cardiac activity seen thereafter. Ultrasound findings suggesting impending pregnancy loss include an abnormally sized or shaped gestational sac and yolk sac, an embryo small for dates, and slow embryonic heart rate. In the absence of signs of miscarriage, more than 95% of pregnancies continue if a live embryo is demonstrated sonographically at 8 weeks gestation. Even in the setting of uterine bleeding, more than two thirds survive as long as ultrasound demonstrates an appropriately sized embryo with a normal cardiac rate. The subsequent pregnancy loss rate is only 1% if a live fetus is seen at 14 to 16 weeks gestation.

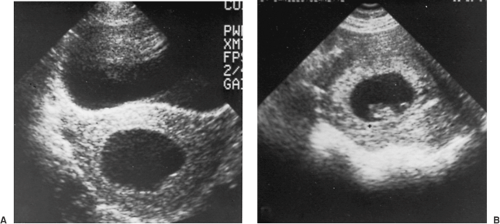

Although there is no convincing evidence that any treatment favorably influences the course of threatened miscarriage, a sympathetic attitude by the physician along with continuing support and follow-up are important to patients. This includes a tactful explanation about the pathologic process and favorable prognosis when the pregnancy is viable. An optimistic but cautious approach is prudent, since a few of these women will have a later embryonic or fetal death. It is reasonable to advise patients to remain available to medical care until it can be determined whether the symptoms will persist or cease. Continued observation is indicated as long as bleeding and cramping are mild, the cervix remains closed, quantitative β-hCG levels are increasing normally, and a normal embryo or fetus is evident on follow-up sonogram. If the bleeding and cramping progressively increase, the prognosis becomes worse. An unfavorable outcome is also associated with negative or falling β-hCG values, sonographic evidence of an embryo or fetus decreasing in size (Fig. 4.4), a slow heart rate, and a uterus that is not increasing in size on pelvic examination.

Inevitable and Incomplete Miscarriage

Miscarriage is considered inevitable when bleeding and cramping is accompanied by gross rupture of the membranes or cervical dilation. The miscarriage is incomplete when the products of conception have partially passed from the uterine cavity, are protruding from the external os, or are in the vagina with persistent bleeding and cramping. There is no viable conceptus in most instances of inevitable or incomplete miscarriages. Rarely, a single twin may survive and continue to term after miscarriage of the other conceptus.

Women with incomplete or inevitable miscarriage typically present with bleeding that can be profuse occasionally and produce hemodynamic instability. A careful pelvic examination is usually sufficient to establish the diagnosis, although ultrasound examination is often performed. Evacuation of the uterus is advisable to prevent further maternal hemorrhage or infection. Clinically stable patients can be treated as outpatients by either medical or surgical means. However, patients with uncontrolled bleeding should be transferred to the operating room for an examination under anesthesia and immediate surgical evacuation of the uterus. They should be observed postoperatively for several hours and discharged when considered stable.

Figure 4.4 Ultrasonic comparison of (A) an anembryonic pregnancy with no fetal tissue that is destined to abort with (B) a normal gestational sac with a transonic area, echogenic rim, and fetal pole. |

Suction curettage can be performed promptly and safely in an inpatient or outpatient setting by using analgesia, a paracervical block, and an intravenous infusion of normal saline containing 10 to 20 U of oxytocin. The cervix is sometimes dilated, and ring forceps can be used to remove products of conception from the cervical canal and lower uterine segment, thereby facilitating uterine contractions and hemostasis. Suction curettage with a plastic curette and vacuum pressure is used to remove the remaining tissue. The curette is rotated 360 degrees clockwise as it is withdrawn, and the procedure is repeated in a counterclockwise direction. When a grating sensation is noted and no more tissue is obtained, the endometrial cavity has been emptied. The tissue obtained should be examined to confirm the presence of products of conception and rule out the possibility of ectopic pregnancy.

Problems that can occur include allergic reactions to medication, uterine atony, uterine perforation, seizure, or cardiac arrest. A complete blood count level should be obtained, and blood replacement may be necessary if hemorrhage occurs. Rh-negative women should receive 50 g (in the first trimester) or the standard 300-g (in the second trimester) dose of Rh immune globulin to prevent Rh immunization.

Medical management of incomplete miscarriage has been studied in well-designed trials and may be used instead of surgical evacuation in clinically stable patients, although uterine curettage may eventually be required. In one randomized, controlled trial, an 80% complete abortion rate was achieved by using 800 mg of misoprostol (four 200-mg tablets) per vagina every 4 hours. Most patients responded to the first dose. Curettage was necessary in 28% of patients. When successful, misoprostol treatment of incomplete miscarriage is associated with lower rates of short- and long-term complications compared with surgical evacuation. Combinations of misoprostol with methotrexate or RU-486 appear promising but are not available for clinical use.

Complete Miscarriage

Patients followed for a threatened miscarriage should be instructed to save all tissue passed for later inspection. When the entire products of conception have passed, pain and bleeding soon cease. If the diagnosis is certain, no further therapy is necessary. In questionable cases, ultrasound is useful to confirm an empty uterus. In some cases, curettage may be necessary to be sure that the uterus is completely evacuated. Removal of remaining necrotic decidua decreases the incidence of bleeding and shortens the recovery time.

Missed Miscarriage

The reason that expulsion of a dead conceptus does not occur despite a prolonged period is uncertain. The patient’s symptoms of pregnancy typically regress, quantitative β-hCG levels fall, and no fetal heart motion is detected by ultrasound. While most patients eventually abort spontaneously, and coagulation defects due to retention of the conceptus are rare, expectant management is emotionally trying, and many women prefer to have the uterus evacuated. Either medical or surgical evacuation of uterine contents is acceptable.

In the second trimester, the uterus can be emptied by dilation and evacuation (D&E) or induction of labor with intravaginal prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) or misoprostol. D&E is an extension of the traditional dilation and curettage (D&C) and vacuum curettage. It is especially appropriate at 13 to 16 weeks gestation, although many proponents use

this procedure through 20 weeks. The cervix is usually first prepared by using misoprostol or passively dilated with laminaria to avoid trauma, and the fetus and placenta are mechanically removed with suction and instruments.

this procedure through 20 weeks. The cervix is usually first prepared by using misoprostol or passively dilated with laminaria to avoid trauma, and the fetus and placenta are mechanically removed with suction and instruments.

If induction of labor is chosen, vaginal PGE2 may be used; one 20-mg suppository is placed high in the posterior vaginal vault every 4 hours until the fetus and placenta are expelled. Between 2.5 and 5.0 mg of diphenoxylate given orally and 10 mg of prochlorperazine given intramuscularly can control diarrhea and nausea, and narcotics or epidural anesthesia can be used to control pain. In this situation, a retained placenta is relatively common and may require manual removal and uterine curettage.

Misoprostol has become more commonly used in recent years because of its equal efficacy and markedly lower incidence of unpleasant side effects; 200-mg tablets are placed high in the vagina every 4 hours until delivery of the fetus and placenta. Medical treatment of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and fever are rarely necessary, although retained placenta is not uncommon.