Otitis Externa

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Acute otitis media (AOM) with tympanic membrane (TM) rupture, furunculosis of the ear canal, and mastoiditis.

Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

Otitis externa (OE) is a cellulitis of the soft tissues of the EAC, which can extend to surrounding structures such as the pinna, tragus, and lymph nodes. Also known as “swimmer’s ear,” humidity, heat, and moisture in the ear are known to contribute to the development of OE, along with localized trauma to the ear canal skin. Sources of trauma may include digital trauma, earplugs, ear irrigations, and the use of cotton-tipped swabs to clean or scratch the ear canal. Keeping the ear “too clean” can also contribute to the development of OE, since cerumen actually serves as a protective barrier to the underlying skin and its acidic pH inhibits bacterial and fungal growth. The most common organisms in OE are Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

Symptoms include pain, aural fullness, decreased hearing, and sometimes itching in the ear. Manipulation of the pinna or tragus causes considerable pain. Discharge may start out as clear then become purulent. It may also cause secondary eczema of the auricle. The ear canal is typically swollen and narrowed, and the patient may resist any attempt to insert an otoscope. Debris is present in the canal and it is usually very difficult to visualize the TM due to canal edema.

Complications

Complications

If untreated, facial cellulitis may result. Immunocompromised individuals can develop malignant OE, which is a spread of the infection to the skull base with resultant osteomyelitis. This is a life-threatening condition.

Treatment

Treatment

Management includes pain control, removal of debris from the canal, topical antimicrobial therapy, and avoidance of causative factors. Fluoroquinolone eardrops are first-line therapy for OE. In the absence of systemic symptoms, children with OE should be treated with antibiotic eardrops only. The topical therapy chosen must be nonototoxic because a perforation or patent tube may be present; if the TM cannot be visualized, then a perforation should be presumed to exist. If the ear canal is too edematous to allow entry of the eardrops, a Pope ear wick (expandable sponge) should be placed to ensure antibiotic delivery. Oral antibiotics are indicated for any signs of invasive infection, such as fever, cellulitis of the face or auricle, or tender periauricular or cervical lymphadenopathy. In such cases, in addition to the ototopical therapy, cultures of the ear canal discharge should be sent, and an antistaphylococcal antibiotic prescribed while awaiting culture results. The ear should be kept dry until the infection has cleared.

Children with intact TMs who are predisposed to external otitis may be prophylaxed with two to three drops of a 1:1 solution of white vinegar and 70% ethyl alcohol in the ears before and after swimming.

Kaushik V, Malik T, Saeed SR: Interventions for acute otitis externa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD004740, 2010 [PMID: 20091565].

Rosenfeld RM et al: Clinical practice guideline: acute otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006 Apr;134(4 Suppl):S4–S23 [PMID: 1668473].

Waitzman AA, et al: Otitis externa, http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/994550-overview. Accessed January 11, 2014.

Bullous Myringitis

Bullous myringitis (BM) is inflammation of the TM with hemorrhagic or serous bullae, and has been associated with viral upper respiratory infections and Streptococcus pneumoniae. It is often very painful and may be associated with otorrhea and decreased hearing. BM is treated with antibiotics, analgesics, anti-inflammatories, and occasionally steroids.

Acute Otitis Media

Acute otitis media (AOM) is the most common reason why antibiotics are prescribed for children in the United States. It is an acute infection of the middle ear space associated with inflammation, effusion, or, if a patent tympanostomy tube or perforation is present, otorrhea (ear drainage).

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Otitis media with effusion (OME), BM, acute mastoiditis, and middle ear mass.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

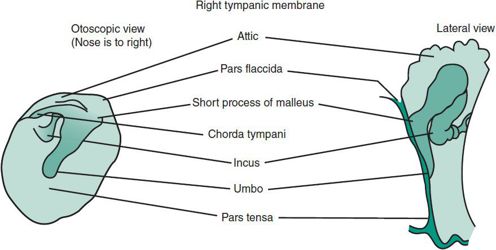

Two findings are critical in establishing a diagnosis of AOM: a bulging TM and a MEE. The presence of MEE is best determined by visual examination and either pneumatic otoscopy or tympanometry (Figure 18–1). In order to distinguish AOM from OME, signs and symptoms of middle ear inflammation and acute infection must be present. Otoscopic findings specific for AOM include a bulging TM, impaired visibility of ossicular landmarks, yellow or white effusion (pus), an opacified and inflamed eardrum, and sometimes squamous exudate or bullae on the eardrum.

Figure 18–1. Tympanic membrane.

Figure 18–1. Tympanic membrane.

A. Pathophysiology and Predisposing Factors

1. Eustachian tube dysfunction (ETD)—The eustachian tube regulates middle ear pressure and allows for drainage of the middle ear. It must periodically open to prevent the development of negative pressure and effusion in the middle ear space. If this does not occur, negative pressure leads to transudation of cellular fluid into the middle ear, as well as influx of fluids and pathogens from the nasopharynx and adenoids. Middle ear fluid may then become infected, resulting in AOM. The eustachian tube of infants and young children is more prone to dysfunction because it is shorter, floppier, wider, and more horizontal than in adults. Infants with craniofacial disorders, such as Down syndrome or cleft palate, may be particularly susceptible to ETD.

2. Bacterial colonization—Nasopharyngeal colonization with S pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, or Moraxella catarrhalis increases the risk of AOM, whereas colonization with normal flora such as viridans streptococci may prevent AOM by inhibiting growth of these pathogens.

3. Viral upper respiratory infections (URI)—URIs increase colonization of the nasopharynx with otitis pathogens. They impair eustachian tube function by causing adenoid hypertrophy and edema of the eustachian tube itself.

4. Smoke exposure—Passive smoking increases the risk of persistent MEE by enhancing colonization, prolonging the inflammatory response, and impeding drainage of the middle ear through the eustachian tube. For infants aged 12–18 months, cigarette exposure is associated with an 11% per pack increase in the duration of MEE.

5. Impaired host immune defenses—Immunocompromised children such as those with selective IgA deficiency usually experience recurrent AOM, rhinosinusitis, and pneumonia. However, most children who experience recurrent or persistent otitis only have selective impairments of immune defenses against specific otitis pathogens.

6. Bottle feeding—Breast-feeding reduces the incidence of acute respiratory infections, provides immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies that reduce colonization with otitis pathogens, and decreases the aspiration of contaminated secretions into the middle ear space which can occur when a bottle is propped in the crib.

7. Time of year—The incidence of AOM correlates with the activity of respiratory viruses, accounting for the annual surge in otitis media cases during the winter months in temperate climates.

8. Daycare attendance—Children exposed to large groups of children have more respiratory infections and OM. The increased number of children in daycare over the past three decades has undoubtedly played a major role in the increase in AOM in the United States.

9. Genetic susceptibility—Although AOM is known to be multifactorial, and no gene for susceptibility has yet been identified, recent studies of twins and triplets suggest that as much as 70% of the risk is genetically determined.

B. Microbiology of Acute Otitis Media

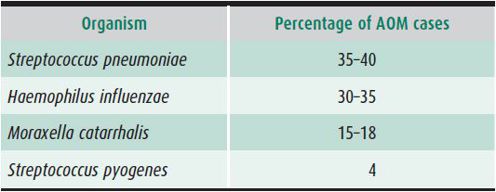

Bacterial or viral pathogens can be detected in up to 96% of middle ear fluid samples from patients with AOM if sensitive and comprehensive microbiologic methods are used. S pneumoniae and H influenzae account for 35%–40% and 30%–35% of isolates, respectively. With widespread use of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine starting in 2000, the incidence of AOM caused by H influenzae rose while that of the S pneumoniae vaccine serotypes declined. However, there has been an increase in disease caused by S pneumoniae serotypes not covered by the vaccine. The third most common pathogen cited is M catarrhalis, which causes up to 15%–25% of AOM cases in the United States (Table 18–1). The fourth most common organism in AOM is Streptococcus pyogenes, which is found more frequently in school-aged children than in infants. S pyogenes and S pneumoniae are the predominant causes of mastoiditis.

Table 18–1. Microbiology of acute otitis media (AOM).

Drug-resistant S pneumoniae is a common pathogen in AOM and strains may be resistant to only one drug class (eg, penicillins or macrolides) or to multiple classes. Children with resistant strains tend to be younger and to have had more unresponsive infections. Antibiotic treatment in the preceding 3 months also increases the risk of harboring resistant pathogens. The prevalence of resistant strains no longer varies significantly among geographic areas within the United States, but it does vary worldwide. Lower incidences are found in countries with less antibiotic use. β-Lactamase resistance is seen in 34%–45% of H influenzae, while M catarrhalis approaches 100%.

C. Examination Techniques and Procedures

1. Pneumatic otoscopy—AOM is overdiagnosed, leading to inappropriate antibiotic therapy, unnecessary surgical referrals and significant associated costs. Contributing to errors in diagnosis is the temptation to accept the diagnosis without removing enough cerumen to adequately visualize the TM, and the mistaken belief that a red TM establishes the diagnosis. Redness of the TM is often a vascular flush caused by fever or crying.

A pneumatic otoscope with a rubber suction bulb and tube is used to assess TM mobility. When used correctly, pneumatic otoscopy can improve diagnostic ability by 15%–25%. The largest possible speculum should be used to provide an airtight seal and maximize the field of view. When the rubber bulb is squeezed, the TM should move freely with a snapping motion; if fluid is present in the middle ear space, the mobility of the TM will be absent or resemble a fluid wave. The ability to assess mobility is compromised by failure to achieve an adequate seal with the otoscope, poor visualization due to low light intensity, and mistaking the ear canal wall for the membrane. The bulb should be slightly compressed when placing the speculum to allow gentle retraction of the TM and avoid discomfort. The tip of the speculum should not be advanced past the cartilaginous EAC to avoid pressure on the bony canal, which is painful. Light, rapid squeezes of the bulb should be undertaken to maximize visualization and minimize pain.

2. Cerumen removal—Cerumen (ear wax) removal is an essential skill for anyone who cares for children. Impacted cerumen pushed against the TM can cause itching, pain, or hearing loss. Parents should be advised that cerumen actually protects the ear and usually comes out by itself through the natural sloughing and migration of the skin of the ear canal. Parents should never put anything into the ear canal to remove wax.

Cerumen may be safely removed under direct visualization through the operating head of an otoscope, provided two adults are present to hold the child. A size 0 plastic disposable ear curette may be used. Irrigation can also be used to remove hard or flaky cerumen. Wax can be softened with 1% sodium docusate solution, carbamyl peroxide solutions, or mineral oil before irrigation is attempted. Irrigation with a soft bulb syringe is performed with water warmed to 35–38°C to prevent vertigo. A commercial jet tooth cleanser (eg, Water Pik) can be used, but it is important to set it at low power to prevent damage to the TM. A perforated TM or patent tympanostomy tube is a contraindication to any form of irrigation.

A home remedy for recurrent cerumen impaction is a few drops of oil such as mineral or olive oil a couple of times a week, warmed to body temperature to prevent dizziness. Droppers are available at pharmacies.

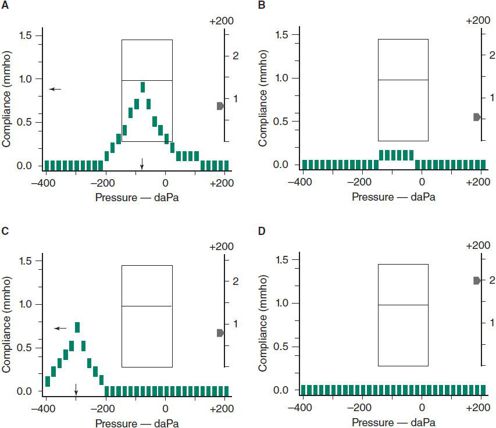

3. Tympanometry—Tympanometry can be helpful in assessing middle ear status, particularly when pneumatic otoscopy is inconclusive or difficult to perform. Tympanometry can reveal the presence or absence of a MEE but cannot differentiate between acutely infected fluid (AOM) and a chronic effusion (OME).

Tympanometry measures TM compliance and displays it in graphic form. It also measures the volume of the ear canal, which can help differentiate between an intact and perforated TM. Standard 226-Hz tympanometry is not reliable in infants younger than 6 months. A high-frequency (1000 Hz) probe is used in this age group.

Tympanograms can be classified into four major patterns, as shown in Figure 18–2. The pattern shown in Figure 18–2A, characterized by maximum compliance at normal atmospheric pressure, indicates a normal TM, good eustachian tube function, and absence of effusion. Figure 18–2B identifies a nonmobile TM with normal volume, which indicates MEE. Figure 18–2C indicates an intact, mobile TM with excessively negative middle ear pressure (greater than –150 daPa), indicative of poor eustachian tube function. Figure 18–2D shows a flat tracing with a large middle ear volume, indicative of a patent tube or TM perforation.

Figure 18–2. Four types of tympanograms obtained with Welch-Allyn MicroTymp 2. A: Normal middle ear. B: Otitis media with effusion or acute otitis media. C: Negative middle ear pressure due to eustachian tube dysfunction. D: Patent tympanostomy tube or perforation in the tympanic membrane. Same as B except for a very large middle ear volume.

Figure 18–2. Four types of tympanograms obtained with Welch-Allyn MicroTymp 2. A: Normal middle ear. B: Otitis media with effusion or acute otitis media. C: Negative middle ear pressure due to eustachian tube dysfunction. D: Patent tympanostomy tube or perforation in the tympanic membrane. Same as B except for a very large middle ear volume.

Treatment

Treatment

A. Pain Management

Pain is the primary symptom of AOM, and the 2013 clinical practice guidelines emphasize the importance of addressing this symptom. As it may take 1–3 days before antibiotic therapy leads to a reduction in pain, mild to moderate pain should be treated with ibuprofen or acetaminophen. Severe pain should be treated with narcotics, but careful and close observation is required to address possible respiratory depression, altered mental status, gastrointestinal upset and constipation. Topical analgesics have a very short duration and studies do not support efficacy in children younger than 5 years.

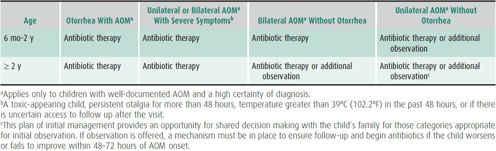

B. The Observation Option

Since the release of clinical practice guidelines in 2004, watchful waiting with close observation has been recommended in certain groups of children with AOM. The updated 2013 guidelines modify the initial recommendations, including the laterality of infection and otorrhea as criteria (Table 18–2). The choice to observe is an option in otherwise healthy children without other underlying conditions such as cleft palate, craniofacial abnormalities, immune deficiencies, cochlear implants, or tympanostomy tubes. The decision should be made in conjunction with the parents, and a mechanism must be in place to provide antibiotic therapy if there is worsening of symptoms or lack of improvement within 48–72 hours. For infants younger than 6 months, antibiotics are always recommended on the first visit, regardless of diagnostic certainty.

Table 18–2. Recommendations for initial management of uncomplicated AOM.a

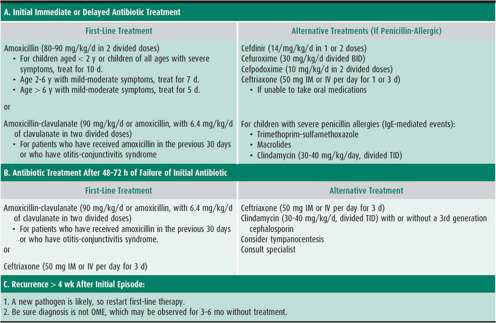

C. Antibiotic Therapy

High-dose amoxicillin remains the first-line antibiotic for treating AOM, even with a high prevalence of drug-resistant S pneumoniae, because data show that isolates of the bacteria remain susceptible to the drug 83%–87% of the time. Amoxicillin is generally considered safe, low-cost, palatable, and has a narrow microbiologic spectrum.

Amoxicillin-clavulanate enhanced strength (ES), with 90 mg/kg/d of amoxicillin dosing (14:1 ratio of amoxicillin:clavulanate), is an appropriate choice when a child has had amoxicillin in the last 30 days, or is clinically failing after 48–72 hours on amoxicillin (Table 18–3). The regular strength formulations of amoxicillin-clavulanate (7:1 ratio) should not be doubled in dosage to achieve 90 mg/kg/d of amoxicillin, because the increased amount of clavulanate will cause diarrhea.

Table 18–3. Antibiotic therapies for acute otitis media.

Three oral cephalosporins (cefuroxime, cefpodoxime, and cefdinir) are more β-lactamase–stable and are alternative choices in children who develop a papular rash with amoxicillin (see Table 18–3). Unfortunately, coverage of highly penicillin-resistant pneumococci with these agents is poor and only the intermediate-resistance classes are covered. Of these drugs, cefdinir suspension is most palatable; the other two have a bitter after-taste which is difficult to conceal. Newer flavoring agents may be helpful here.

A second-line antibiotic is indicated when a child experiences symptomatic infection within 1 month of finishing amoxicillin; however, repeat use of high-dose amoxicillin is indicated if more than 4 weeks have passed without symptoms. Macrolides such as azithromycin and clarithromycin are not recommended as second-line agents because S pneumoniae is resistant to macrolides in approximately 30% in respiratory isolates, and because virtually all strains of H influenzae have an intrinsic macrolide efflux pump, which pumps antibiotic out of the bacterial cell.

Reasons for failure to eradicate a sensitive pathogen include drug noncompliance, poor drug absorption, or vomiting of the drug. If a child remains symptomatic for longer than 3 days while taking a second-line agent, a tympanocentesis is useful to identify the causative pathogen. If a highly resistant pneumococcus is found or if tympanocentesis is not feasible, intramuscular ceftriaxone at 50 mg/kg/dose for 3 consecutive days is recommended. If a child has experienced a severe reaction, such as anaphylaxis, to amoxicillin, cephalosporins should not be substituted. Otherwise, the risk of cross-sensitivity is less than 0.1%. Multi-drug resistant S pneumoniae poses a treatment dilemma and newer antibiotics may need to be employed such as fluoroquinolones or linezolid. However, these drugs are not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of AOM in children.

In patients with tympanostomy tubes with uncomplicated acute otorrhea, ototopical antibiotics (fluoroquinolone eardrops) are first-line therapy. The eardrops serve two purposes: (1) They treat the infection and (2) they physically “rinse” drainage from the tube which helps prevent plugging of the tube. Oral antibiotics are not indicated in the absence of systemic symptoms.

D. Tympanocentesis

Tympanocentesis is performed by placing a needle through the TM and aspirating the middle ear fluid. The fluid is sent for culture and sensitivity. Indications for tympanocentesis are (1) AOM in an immunocompromised patient, (2) research studies, (3) evaluation for presumed sepsis or meningitis, such as in a neonate, (4) unresponsive otitis media despite courses of two appropriate antibiotics, and (5) acute mastoiditis or other suppurative complications. Tympanocentesis can be performed with an open-headed operating otoscope or a binocular microscope with either a spinal needle and 3-mL syringe, or if available, an Alden-Senturia trap (Storz Instrument Co., St. Louis, MO) or the Tymp-Tap aspirator (Xomed Surgical Products, Jackson, FL) (Figure 18–3).

Figure 18–3. Operating head and Alden-Senturia trap for tympanocentesis. Eighteen-gauge spinal needle is attached and bent.

Figure 18–3. Operating head and Alden-Senturia trap for tympanocentesis. Eighteen-gauge spinal needle is attached and bent.

E. Prevention of Acute Otitis Media

1. Antibiotic prophylaxis—Strongly discouraged. Antibiotic resistance is a concern and studies have shown poor efficacy.

2. Lifestyle modifications—Parental education plays a major role in decreasing AOM. These are some items to consider in children with RAOM:

• Smoking is a risk factor both for upper respiratory infection and AOM. Primary care physicians can provide information on smoking cessation programs and measures.

• Breast-feeding protects children from AOM. Clinicians should encourage exclusive breast-feeding for 6 months.

• Bottle-propping in the crib should be avoided. It increases AOM risk due to the reflux of milk into the eustachian tubes.

• Pacifiers are controversial. In Finland, removing pacifiers from infants was shown to reduce AOM episodes by about one-third compared to a control group. The mechanism is uncertain but likely to be related to effects on the eustachian tube. However, the benefit of pacifier use in reducing sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS)–related deaths is also important to consider. Currently, the recommendation from the American Academy of Family Physicians is to wean a pacifier if used after 6 months of age to reduce the risk of AOM.

• Day care is a risk factor for AOM, but working parents may have few alternatives. Possible alternatives include care by relatives or child care in a setting with fewer children.

3. Surgery—Tympanostomy tubes are effective in the treatment of recurrent AOM as well as OME.

4. Immunologic evaluation and allergy testing—While immunoglobulin subclass deficiencies may be more common in children with recurrent AOM, there is no practical immune therapy available. More serious immunodeficiencies, such as selective IgA deficiency, should be considered in children who suffer from a combination of recurrent AOM, rhinosinusitis, and pneumonia. In the school-aged child or preschooler with an atopic background, skin testing may be beneficial in identifying allergens that can predispose to AOM.

5. Vaccines—The pneumococcal conjugate and influenza vaccines are recommended. The seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) has been used in the United States since 2000, and the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) was introduced in 2010. PCV7 was found to produce a 29% reduction in AOM resulting from the seven serotypes found in the vaccine, and overall, PCV7 reduced AOM by 6%–7%, according to a 2009 Cochrane database review. Data are not yet available regarding the effect of PCV13 on AOM at this time. In recent studies, intranasal influenza vaccine reduced the number of influenza-associated cases of AOM by 30%–55%.

Jones WH, Kaleida PH: How helpful is pneumatic otoscopy in improving diagnostic accuracy? Pediatrics 2003;112;510 [PMID: 12949275].

Lieberthal AS, et al: The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics 2013; 131:e964-e999 [PMID: 23439909].

Wald E: Acute otitis media and acute bacterial sinusitis. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52(S4):S277–S283 [PMID: 21460285].

Sexton S, Natale R: Risks and benefits of pacifiers. Am Fam Physician 2009 Apr 15;79(8):681–685 [PMID: 19405412].

Stockmann C et al: Seasonality of acute otitis media and the role of respiratory viral activity in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2012 Dec 17; 314-319 [PMID: 23249910].

Web Resources

http://www.entnet.org/HealthInformation/. Accessed January 11, 2014.

http://www.entnet.org/EducationAndResearch/upload/AAO-PGS-9-4-2.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2014.

http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/. Accessed January 11, 2014.

Otitis Media With Effusion

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

Otitis media with effusion (OME) is the presence of fluid in the middle ear space without signs or symptoms of acute inflammation. There may be some discomfort, but acute pain is not characteristic. A retracted or neutral TM with decreased mobility is seen on pneumatic otoscopy. The TM may be opacified or may have a whitish or amber discoloration.

Children with OME can develop AOM if the middle ear fluid should become infected. OME often follows an episode of AOM. After AOM, fluid can remain in the ear for several weeks, with 60%–70% of children still having MEE 2 weeks after successful treatment. This drops to 40% at 1 month and 10%–25% at 3 months after treatment. It is important to distinguish OME from AOM because the former does not benefit from treatment with antibiotics.

Management

Management

An audiology evaluation should be performed after approximately 3 months of continuous bilateral effusion in children younger than 3 years and those at risk of language delay due to socioeconomic circumstances, craniofacial anomalies, or other risk factors. Children with hearing loss or speech delay should be referred to an otolaryngologist for possible tympanostomy tube placement. Antibiotics, antihistamines and steroids have not been shown to be useful in the treatment of OME

Traditionally, OME was observed for 3 months in uncomplicated cases prior to consideration for tympanostomy tube placement. More recent studies have found that longer periods of observation do not necessarily have significant negative effects on literacy, attention, academic achievement, and social skills. Longer periods of observation may be acceptable in children with normal or very mild hearing loss on audiogram, no risk factors for speech and language issues, and no structural changes to the TM. Absolute indications for tympanostomy tubes include hearing loss greater than 40 dB, TM retraction pockets, ossicular erosion, adhesive atelectasis, and cholesteatoma. If a patient clears a persistent MEE, the physician should follow the patient monthly.

Prognosis & Sequelae

Prognosis & Sequelae

Prognosis is variable based on age of presentation. Infants who are very young at the time of first otitis media are more likely to need surgical intervention. Other factors that decrease the likelihood of resolution are onset of OME in the summer or fall, history of prior tympanostomy tubes, presence of adenoids, and hearing loss greater than 30 dB.

The presence of biofilms has been found to explain the “sterile” effusion sometimes present when culturing middle ear fluid in OME. On electron microscopy, biofilms have been found to cover the middle ear mucosa and adenoids in up to 80% of patients with OME. Currently, work is being done to find ways to eradicate biofilms, including physical disruption, reduction, and eradication.

Paradise JL et al; Tympanostomy tubes and developmental outcomes at 9 to 11 years of age. New Eng J Med 2007;356:3 [PMID: 17229952].

Rosenfeld RM et al: Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004;130:S95 [PMID: 15138413].

Smith A, Buchinsky FJ, Post JC: Eradicating chronic ear, nose, and throat infections: a systematically conducted literature review of advances in biofilm treatment. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2011 Mar;144(3):338–347 [Review] [PMID: 21493193].

Complications of Otitis Media

Complications of Otitis Media

A. Tympanosclerosis, Retraction Pockets, Adhesive Otitis

Tympanosclerosis is an acquired disorder of calcification and scarring of the TM and middle ear structures from inflammation. The term myringosclerosis applies to calcification of the TM only, and is a fairly common sequela of OME and AOM. Myringosclerosis may also develop at the site of a previous tympanostomy tube; tympanosclerosis is not a common sequela of tube placement. If tympanosclerosis involves the ossicles, a conductive hearing loss may result. Myringosclerosis rarely causes a hearing loss, unless the entire TM is involved (“porcelain eardrum”). Myringosclerosis may be confused with a middle ear mass. However, use of pneumatic otoscopy can often help in differentiation, as the plaque will move with the TM during insufflation.

The appearance of a small defect or invagination of the pars tensa or pars flaccida of the TM suggests a retraction pocket. Retraction pockets occur when chronic inflammation and negative pressure in the middle ear space produce atrophy and atelectasis of the TM.

Continued inflammation can cause adhesions to form between the retracted TM and the ossicles. This condition, referred to as adhesive otitis, predisposes one to formation of a cholesteatoma or fixation and erosion of the ossicles.

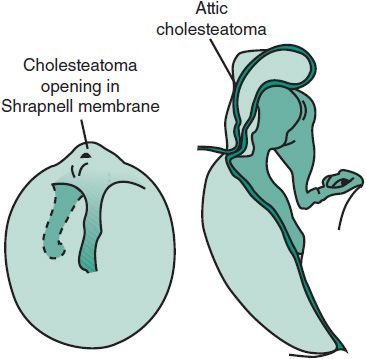

B. Cholesteatoma

A greasy-looking mass or pearly white mass seen in a retraction pocket or perforation suggests a cholesteatoma (Figure 18–4). If infection is superimposed, serous or purulent drainage will be seen, and the middle ear cavity may contain granulation tissue or even polyps. Persistent, recurrent, or foul smelling otorrhea following appropriate medical management should make one suspect a cholesteatoma.

Figure 18–4. Attic cholesteatoma, formed from an in-drawing of an attic retraction pocket.

Figure 18–4. Attic cholesteatoma, formed from an in-drawing of an attic retraction pocket.

C. Tympanic Membrane Perforation

Occasionally, an episode of AOM may result in rupture of the TM. Discharge from the ear is seen, and often there is rapid relief of pain. Perforations due to AOM usually heal spontaneously within a couple of weeks. Ototopical antibiotics are recommended for a 10- to 14-day course and patients should be referred to an otolaryngologist 2–3 weeks after the rupture for examination and hearing evaluation.

When perforations fail to heal after 3–6 months, surgical repair may be needed. TM repair is generally delayed until the child is older and eustachian tube function has improved. Procedures include paper patch myringoplasty, fat myringoplasty, and tympanoplasty. Tympanoplasty is generally deferred until around 7 years of age, which is approximately when the eustachian tube reaches adult orientation. In otherwise healthy children, some surgeons perform a repair earlier if the contralateral, nonperforated ear remains free of infection and effusion for 1 year.

In the presence of a perforation, water activities should be limited to surface swimming, preferably with the use of an ear mold.

D. Facial Nerve Paralysis

The facial nerve traverses the middle ear as it courses through the temporal bone to its exit at the stylomastoid foramen. Normally, the facial nerve is completely encased in bone, but occasionally bony dehiscence in the middle ear is present, exposing the nerve to infection and making it susceptible to inflammation during an episode of AOM. The acute onset of a facial nerve paralysis should not be deemed idiopathic Bell palsy until all other causes have been excluded. If middle ear fluid is present, prompt myringotomy and tube placement are indicated. CT is indicated if a cholesteatoma or mastoiditis is suspected.

E. Chronic Suppurative Otitis Media

Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) is present when persistent otorrhea occurs in a child with tympanostomy tubes or TM perforations. It starts with an acute infection that becomes chronic with mucosal edema, ulceration, and granulation tissue. The most common associated bacteria include P aeruginosa, S aureus, Proteus species, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and diphtheroids. Visualization of the TM, meticulous cleaning with culture of the drainage, and appropriate antimicrobial therapy, usually topical, are the keys to management.

Occasionally, CSOM may be a sign of cholesteatoma or other disease process such as foreign body, neoplasm, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, tuberculosis, granulomatosis, fungal infection, or petrositis. If CSOM is not responsive to culture-directed treatment, imaging and biopsy may be needed to rule out other possibilities. Patients with facial palsy, vertigo, or other CNS signs should be referred immediately to an otolaryngologist.

Roland PS, et al: Chronic suppurative otitis media. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/859501-overview. Accessed January 11, 2014.

F. Labyrinthitis

Suppurative infections of the middle ear can spread into the membranous labyrinth of the inner ear through the round window membrane or abnormal congenital communications. Symptoms include vertigo, hearing loss, fevers, and the child often appears extremely toxic. Intravenous antibiotic therapy is used, and intravenous steroids may also be used to help decrease inflammation. Sequelae can be serious, including a condition known as labyrinthitis ossificans, or bony obliteration of the inner ear including the cochlea, leading to profound hearing loss.

Mastoiditis

Mastoiditis

Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

Mastoiditis occurs when infection spreads from the middle ear space to the mastoid portion of the temporal bone, which lies just behind the ear and contains air-filled spaces. Mastoiditis can range in severity from inflammation of the mastoid periosteum to bony destruction of the mastoid air cells (coalescent mastoiditis) with abscess development. Mastoiditis can occur in any age group, but more than 60% of the patients are younger than 2 years. Many children do not have a prior history of recurrent AOM.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Patients with mastoiditis usually have postauricular pain, fever, and an outwardly displaced pinna. On examination, the mastoid area often appears indurated and red. With disease progression it may become swollen and fluctuant. The earliest finding is severe tenderness on mastoid palpation. AOM is almost always present. Late findings include a pinna that is pushed forward by postauricular swelling and an ear canal that is narrowed due to pressure on the posterosuperior wall from the mastoid abscess. In infants younger than 1 year, the swelling occurs superior to the ear and pushes the pinna downward rather than outward.

B. Imaging Studies

The best way to determine the extent of disease is by computed tomography (CT) scan. Early mastoiditis may be radiographically indistinguishable from AOM, with both showing opacification but no destruction of the mastoid air cells. With progression of mastoiditis, coalescence of the mastoid air cells is seen.

C. Microbiology

The most common pathogens are S pneumoniae followed by H influenzae and S pyogenes . Rarely, gram-negative bacilli and anaerobes are isolated. Antibiotics may decrease the incidence and morbidity of acute mastoiditis. However, acute mastoiditis still occurs in children who are treated with antibiotics for an acute ear infection. In the Netherlands, where only 31% of AOM patients receive antibiotics, the incidence of acute mastoiditis is 4.2 per 100,000 person-years. In the United States, where more than 96% of patients with AOM receive antibiotics, the incidence of acute mastoiditis is 2 per 100,000 person-years. Moreover, despite the routine use of antibiotics, the incidence of acute mastoiditis has been rising in some cities. The pattern change may be secondary to the emergence of resistant S pneumoniae.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Lymphadenitis, parotitis, trauma, tumor, histiocytosis, OE, and furuncle.

Complications

Complications

Meningitis can be a complication of acute mastoiditis and should be suspected when a child has associated high fever, stiff neck, severe headache, or other meningeal signs. Lumbar puncture should be performed for diagnosis. Brain abscess occurs in 2% of mastoiditis patients and may be associated with persistent headaches, recurring fever, or changes in sensorium. Facial palsy, sigmoid sinus thrombosis, epidural abscess, cavernous sinus thrombosis, and thrombophlebitis may also be encountered.

Treatment

Treatment

In the preantibiotic era, up to 20% of patients with AOM underwent mastoidectomy for mastoiditis. Now, the occurrence is 5 cases per 100,000 persons with AOM. Intravenous antibiotic treatment alone may be successful if there is no evidence of coalescence or abscess on CT. However, if there is no improvement within 24–48 hours, surgical intervention should be undertaken. Minimal surgical management starts with tympanostomy tube insertion, during which cultures are taken. If a subperiosteal abscess is present, incision and drainage is also performed, with or without a cortical mastoidectomy. Intracranial extension requires complete mastoidectomy with decompression of the involved area.

Antibiotic therapy (intravenous and topical ear drops) is instituted along with surgical management and relies on culture directed antibiotic therapy for 2–3 weeks. An antibiotic regimen should be chosen which is able to cross the blood-brain barrier. After significant clinical improvement is achieved with parenteral therapy, oral antibiotics are begun and should be continued for 2–3 weeks. A patent tympanostomy tube must also be maintained, with continued use of otic drops until drainage abates.

Prognosis

Prognosis

Prognosis for full recovery is good. Children that develop acute mastoiditis with abscess as their first ear infection are not necessarily prone to recurrent otitis media.

Bakhos D et al: Conservative management of acute mastoiditis in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2011 Apr;137(4):346–350 [PMID: 21502472].

Brook I: Pediatric mastoiditis. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/966099-overview. Accessed January 11, 2014.

ACUTE TRAUMA TO THE MIDDLE EAR

Head injuries, a blow to the ear canal, sudden impact with water, blast injuries, or the insertion of pointed objects into the ear canal can lead to perforation of the TM, ossicular disruption, and hematoma of the middle ear. One study reported that 50% of serious penetrating wounds of the TM were due to parental use of a cotton swab.

Treatment of middle ear trauma consists mainly of watchful waiting. An audiogram may show a conductive hearing loss. Antibiotics are not necessary unless signs of infection appear. The prognosis for normal hearing depends on whether the ossicles have been dislocated or fractured. The patient needs to be followed with audiometry or by an otolaryngologist until hearing has returned to normal, which is expected within 6–8 weeks. A CT scan may be needed to evaluate the middle ear structures. Occasionally, middle ear trauma can lead to a perilymphatic fistula (PLF) which is disruption of the barrier between the middle ear and inner ear, usually in the area of the oval window. PLF can occur from an acute blow to the ear, foreign body, or occasionally from more innocuous mechanisms such as Valsalva or sneezing. Symptoms include sudden hearing loss and vertigo. This requires emergent otolaryngology evaluation.

Traumatic TM perforations should be referred to an otolaryngologist for examination and hearing evaluation. Spontaneous healing may occur within 6 months of the perforation. If the perforation is clean and dry and there is no hearing change, there is no urgency for specialty evaluation. In the acute setting, antibiotic eardrops are often recommended to provide a moist environment which is thought to speed healing.

CERUMEN IMPACTION AND EAR CANAL FOREIGN BODY

Foreign bodies in the ear are common, whether intentional (self-placement, placement by another child) or accidental (eg, insect, broken-off cotton swab after cleaning attempt). Cerumen can also be obstructive, acting like a foreign body. If the cerumen or object is large or difficult to remove with available instruments, otolaryngology referral is recommended, as the child may be traumatized by further removal attempts, and trauma to the ear canal may cause edema, necessitating removal under general anesthesia. Vegetable matter should never be irrigated as it can swell causing increased pain and removal difficulty. An emergency condition exists if the foreign body is a disk-type battery, such as those used in clocks, watches, and hearing aids. An electric current is generated in the moist canal, and a severe burn can occur in less than 4 hours. If the TM cannot be visualized, assume a perforation and avoid irrigation or ototoxic medications.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree