Gastroschisis and Omphalocele

INTRODUCTION

Gastroschisis and omphalocele (also referred to as exomphalos) are 2 of the most common abdominal wall defects requiring neonatal intensive care. Their similarities, most notably evisceration of abdominal structures through a defect at or near the umbilicus, misled generations of physicians and surgeons to inaccurately diagnose them as a single common disease. The pathologic differences between these 2 entities were formally realized when, in 1953, Thomas Moore and George Stokes defined gastroschisis as a large extraumbilical evisceration of intestines without a covering sac. They distinguished this from omphalocele, which was defined as the herniation of viscera into the base of the umbilical cord with a protective membranous sac.1 The establishment of gastroschisis and omphalocele as 2 distinct pathologies with their own specific anatomic features and associated anomalies provides the basis for our management of these defects today.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Historically, omphalocele was observed nearly twice as commonly as gastroschisis. More recent literature shows an increase in the incidence of gastroschisis,2–4 suggesting that the actual relationship is approximately 1:1. This phenomenon remains unexplained but is probably related to a combination of improved diagnostic coding (prior to the incorporation of Moore and Stokes’s definition, gastroschisis was commonly referred to as omphalocele) and the environmental factors noted in the discussion that follows. The approximate incidence is 1–3 per 10,000 live births for both gastroschisis and omphalocele.4

Population studies have found associations between a number of environmental factors and gastroschisis. Young maternal age (<20 years) reproducibly correlates with gastroschisis, while individual studies have found gastroschisis to be associated with low economic status, maternal use of over-the-counter vasoactive medications or salicylates, maternal smoking, alcohol consumption, and illicit substance use.2,5–8 Omphalocele, on the other hand, is associated with advanced maternal age and karyotype abnormalities.5,7,9

GENETICS

The genetic basis for gastroschisis is poorly understood. Gastroschisis is most frequently sporadic, but there are rare familial cases documented in the literature, suggesting an underlying genetic component. Such case reports include concordance for gastroschisis in monozygotic twins,10,11 dizygotic twins,12 and distant relatives.13

Genotype analysis of patients with gastroschisis has led to the identification of associated single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at the genes encoding endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NOS3/eNOS; odds ratio [OR] 1.9, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1–3.4); intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1; OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.1–3.4); and atrial natriuretic peptide precursor α (NPPA; OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.0–3.4).14 Both ICAM and NOS3/eNOS are intimately involved in the molecular cascades of angiogenesis.15 Although inconclusive, these studies lend some weight to the vasculogenic theories of pathogenesis discussed in the following section. Interestingly, when these polymorphisms were analyzed in mothers who smoked during pregnancy, the odds ratio for developing gastroschisis increased substantially (NOS3/eNOS OR 5.2, 95% CI 2.4–11.4; ICAM1 OR 5.2, 95% CI 2.1–12.7; NPPA OR 6.4, CI 2.8–14.6), providing evidence for a gene-environment interaction.14

Omphalocele, in comparison, is associated with significant chromosomal abnormalities in approximately 30% of cases.4 Trisomy 13, 18, and 21 are the most common karyotype abnormalities. Other genes have been implicated, including pituitary homeobox 2 (PITX2), a gene mutated frequently in Reiger syndrome16; insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1C (CDKN1C), both associated with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome17; and MTHFR, 677C-T, a polymorphism in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene.18 Whether a causal relationship exists between these specific mutations and omphalocele remains to be defined.

EMBRYOLOGY

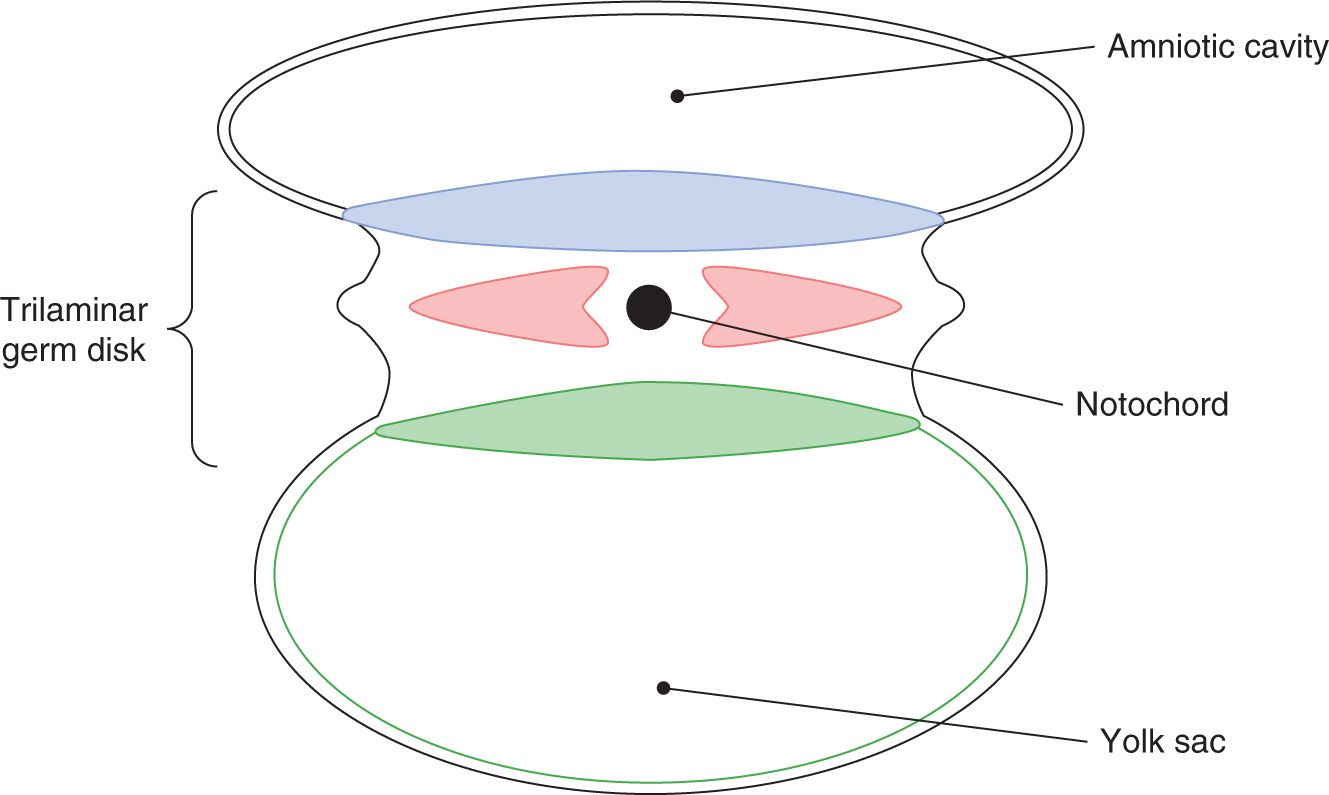

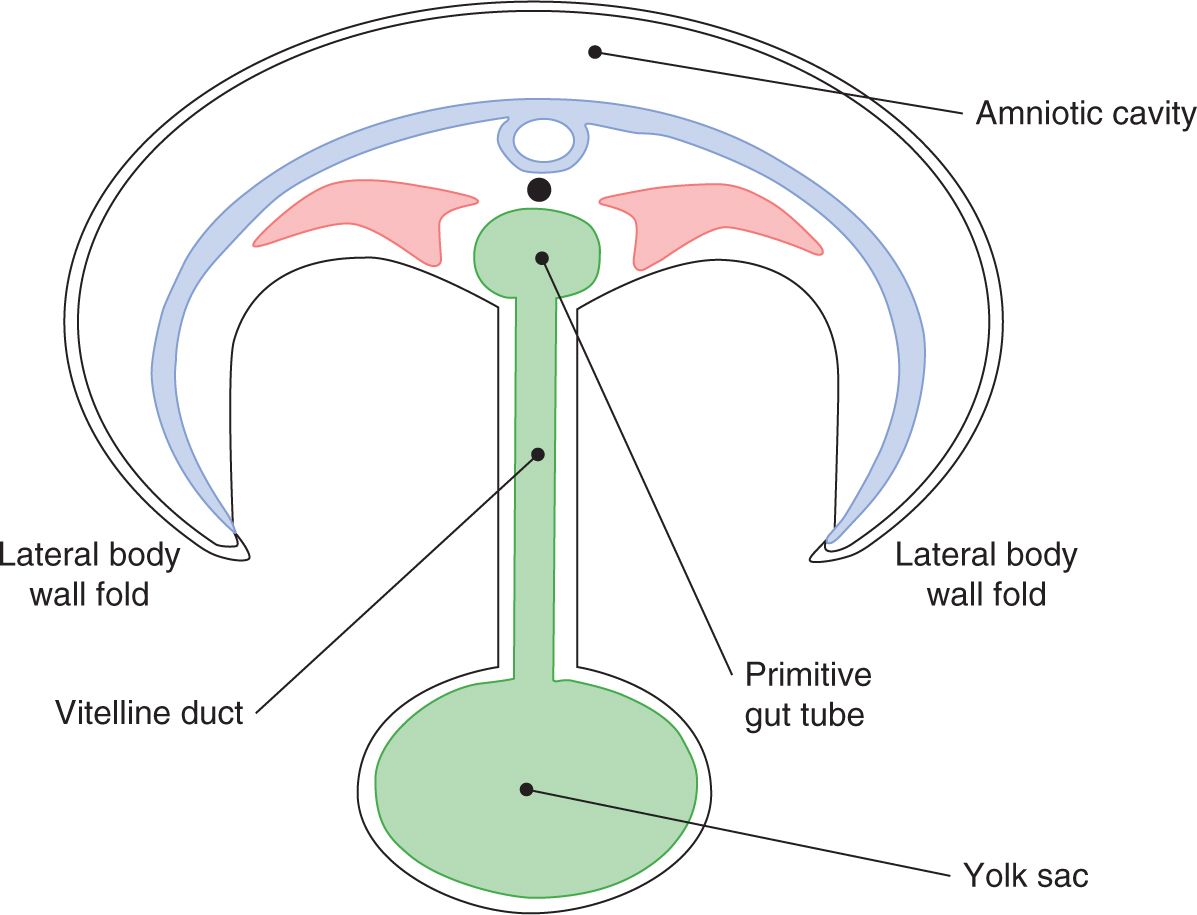

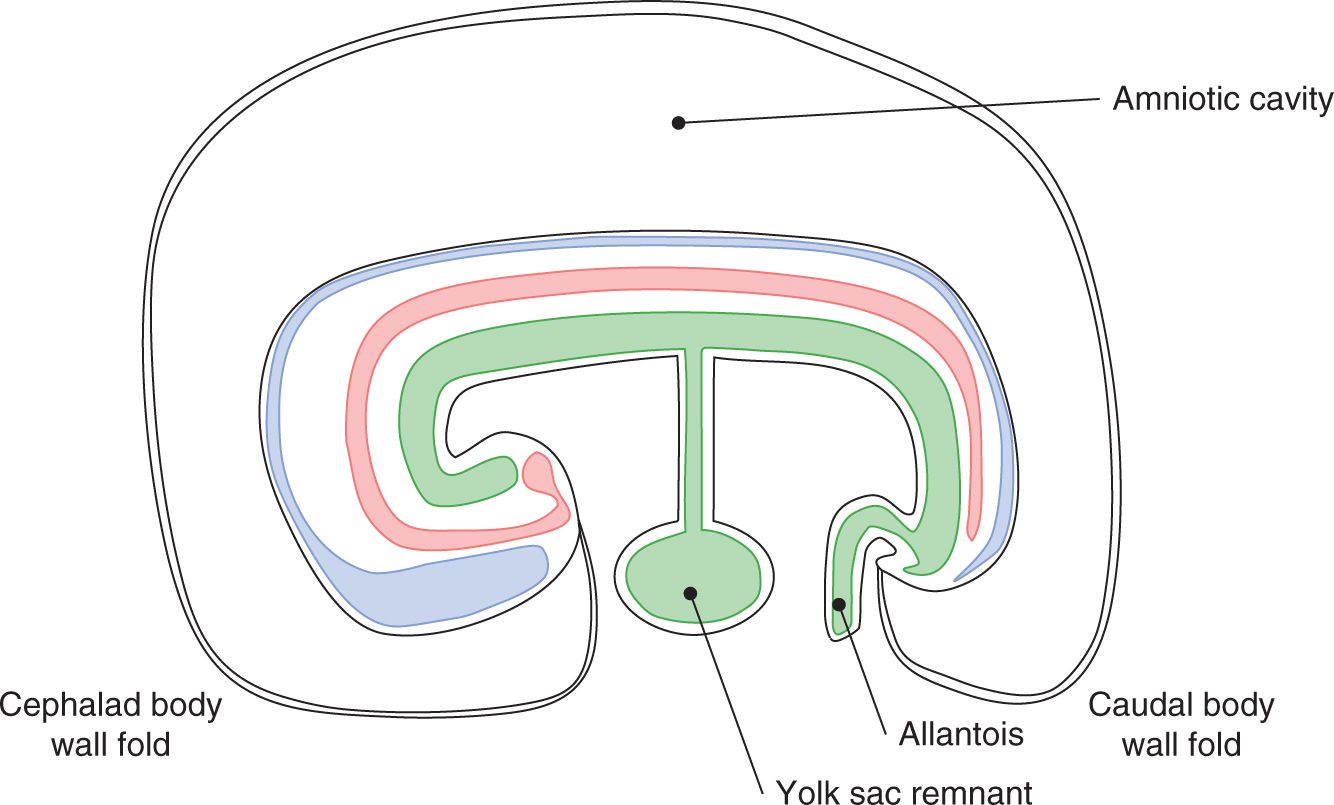

A sound understanding of the basic embryology of the ventral body wall is important for comprehending the pathology and management of abdominal wall defects. During the third week of gestation, the process of gastrulation leads to the formation of a trilaminar germ disk with an identifiable mesoderm sandwiched between the primitive ectoderm and endoderm (Figure 35-1). The subsequent rapid growth of the ectoderm and the mesoderm causes ventral folding of the embryo. The 4 body folds (cranial, caudal, and 2 lateral folds) approximate in the middle of the ventral surface to form the umbilicus (Figures 35-2 and 35-3).

FIGURE 35-1 Formation of a trilaminar germ disk.

FIGURE 35-2 Beginning of umbilicus formation.

FIGURE 35-3 Approximation of the body folds to form the umbilicus.

During the sixth week of gestation, the rapid growth of the midgut leads to physiologic herniation at the base of the umbilicus. As the fetus grows, the intestine rotates 270° in the counterclockwise direction and returns to the peritoneal cavity spontaneously by the 10th week of gestation. Omphalocele is believed to arise from incomplete folding of the lateral body wall folds and failure of the intestines to return to the peritoneal cavity following this physiologic herniation.19,20 As a result, intestinal nonrotation is almost always observed in infants with omphalocele. Importantly, the umbilical stalk persists as a broad-based protective sac and is composed of peritoneum and amnion with an intervening layer of Wharton’s jelly.

Variants of omphalocele occur in the epigastrium and the infraumbilical region. The embryopathology of epigastric omphalocele is related to failure of the cranial body wall-folding process. This defect is often seen in combination with sternal cleft, ectopia cordis/cardiac defects, pericardial defects, and diaphragmatic hernia. When present concurrently, these defects are known as the pentalogy of Cantrell.21 Infraumbilical omphalocele is thought to arise from a deficit in caudal body wall folding and is frequently associated with bladder or cloacal exstrophy.

Following successful ventral body wall folding, the early umbilical contents consist of the yolk stalk and its associated vitelline vessels, the umbilical vessels, and the allantois. The yolk sac maintains its connection to the embryonic intestine through the vitelline duct. It receives its blood supply from the vitelline arteries, which are a network of arteries originating from the dorsal aorta. As the yolk sac atrophies and the nutritional requirements of the fetus are supplied by the placenta and maternal circulation, the vitelline arteries regress. The proximal arterial segments persist as the celiac, superior mesenteric, and inferior mesenteric arteries, supplying the foregut, midgut, and hindgut, respectively.

The umbilical vessels supply the maternal-fetal circulation. The umbilical arteries are paired branches originating at the fetal iliac arteries and carry deoxygenated blood back to the maternal circulation through the umbilical cord. Postnatally, the umbilical arteries regress and become the medial umbilical ligaments, while the closely associated urachus (conduit from the fetal bladder to the allantois) fibroses to become the median umbilical ligament. The umbilical veins, on the other hand, carry oxygenated maternal blood to the fetus. The right umbilical vein regresses early in development; the left umbilical vein persists as the conduit from the placenta to the fetal central venous system. Postnatally, the left umbilical vein atrophies to become the ligamentum teres, the intrahepatic portion of which is known as the ligamentum venosum.

While the exact embryologic etiology of gastroschisis remains much more controversial than that of omphalocele, a number of leading theories have emerged from the last half century, including the following:

1. Similar to omphalocele, failed reduction of the herniated bowel at the 10th week of gestation followed by rupture of the membrane at the base of the umbilical cord lead to the unprotected evisceration characteristic of gastroschisis.22

2. Early teratogen exposure interferes with mesenchymal differentiation, leading to an area of weakness just lateral to the umbilicus.23

3. Incomplete body wall folding leads to failed fusion of the yolk sac with the umbilical stalk, leaving the yolk sac as a lead point for herniation.24

4. Untimely involution or disruption of the vitelline artery leads to body wall ischemia and necrosis.25

5. Abnormal involution of the right umbilical vein leads to an area of weakness and extended apoptosis in the surrounding mesenchyme, resulting in resorption of the body wall at this location.26

While these theories are thought provoking, definitive evidence is lacking in each case. The first theory does not explain the differences in environmental risk factors, maternal characteristics, or associated anomalies observed between gastroschisis and omphalocele. The second and third theories struggle to explain the right-sided predilection of the abdominal wall defect. In contradiction to the fourth theory is the fact that the abdominal wall receives the majority of its circulation from segmental perforating vessels originating at the aorta, not from the vitelline arteries. The umbilical vein theory, put forth by deVries in 1980, has been favored as it both explains the right-sided preponderance of the defect and fits with the genetic associations suggesting a vasculogenic etiology. This theory has also been supported by rare cases of left-sided gastroschisis found to have resorption of the left umbilical vein.27

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Gastroschisis

Gastroschisis is a congenital malformation resulting in a lateral abdominal wall defect almost always 1 to 2 cm to the right of the umbilicus (Figure 35-4). The eviscerated structures do not have a protective sac and are in direct contact with the amniotic fluid, leading to the characteristic edematous, foreshortened, fibrinous peel-covered small bowel. In the absence of significant gastrointestinal morbidity, the long-term outcomes are generally good.

FIGURE 35-4 Gastroschisis is a congenital lateral abdominal wall defect.

Gastroschisis tends to occur as an isolated malformation. Comorbidities in the neonatal period are almost always directly related to the gastrointestinal tract and include intestinal atresia, stenosis, and nonrotation. Approximately 10% of infants born with gastroschisis will have a concurrent intestinal atresia.28,29 The exact etiology of this phenomenon is unknown, but it is thought to be related to an in utero vascular accident, either volvulus or compression of the bowel at the abdominal wall defect. Like omphalocele, intestinal nonrotation is frequently encountered in affected individuals. In nonrotation, the small bowel occupies the right abdomen, the large bowel occupies the left abdomen, and there is a relatively wide mesentery; thus, the risk of volvulus is negligible. In fact, a Ladd procedure for rotational anomalies that is designed to prevent volvulus leaves the bowel in a nonrotated configuration.

Gastroschisis is almost ubiquitously associated with delayed initiation of enteral feeding and intestinal hypomotility. There is evidence to suggest that this is directly related to the damaging effects of in utero intestinal exposure to amniotic fluid and constriction of the intestines at the body wall.30 Supporting this theory are animal studies in which removal of allantoic fluid (ie, urine) from the amniotic cavity31 or complete amniotic fluid replacement32 prevented the development of the characteristic edematous, fibrinous peel-covered intestine.

Prematurity is frequently associated with gastroschisis, with up to 28% of affected individuals delivered spontaneously at less than 37 weeks’ gestation.33 The complications frequent to prematurity and low birth weight are also observed in the setting of gastroschisis. Most notably, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) occurs in these individuals with a predilection for infants weighing less than 2500 kg at birth.34 Furthermore, NEC can emerge as a complication following abdominal closure and the initiation of enteral feeds in these patients, regardless of gestational age.

Omphalocele

Omphalocele is a congenital malformation that results in a midline abdominal wall defect at the umbilicus (Figure 35-5). Less-common variants occur in the epigastrium or infraumbilical region. The eviscerated contents are contained within a protective sac and are not in contact with the amniotic fluid. The eviscerated structures almost always include small bowel and colon; solid organs, most frequently liver, are often involved. Omphalocele is associated with other anomalies approximately 50%–70% of the time, with 30%–50% of affected infants having significant congenital cardiac disease.4 Long-term outcomes are dependent on the severity of the associated anomalies.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree