Disorders of Sex Development

Disorders of Sex Development

Ari J. Wassner

Norman P. Spack

I. DEFINITION AND NOMENCLATURE.

The term

disorders of sex development (DSD) is preferred over older terms such as

ambiguous genitalia, pseudohermaphroditism, and

intersex to denote atypical development of genetic, gonadal, and phenotypic sex (see

Table 61.1). Examples of DSD presenting in the newborn period include infants with the following findings:

A penis and bilaterally nonpalpable testes.

Unilateral cryptorchidism with hypospadias.

Penoscrotal or perineoscrotal hypospadias, with or without microphallus, even if the testes are descended.

Apparently female appearance with enlarged clitoris or inguinal hernia.

Overtly abnormal genital development such as cloacal exstrophy.

Asymmetry of labioscrotal folds, with or without cryptorchidism.

Discordance of external genitalia with prenatal karyotype. Since internal genital anatomy, karyotype, and sex assignment cannot be determined from a baby’s external appearance, a thorough evaluation is required. The evaluation must be expedited because of conditions such as salt-wasting congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) that could be life threatening within the first weeks of life.

II. IMMEDIATE POSTNATAL CONSIDERATIONS PRIOR TO SEX ASSIGNMENT.

While the rapid determination of sex assignment is essential for the parents’ peace of mind, care must be taken to avoid drawing premature conclusions. Prompt consultation with a pediatric endocrinologist will facilitate the evaluation, and most causes of DSD can be clarified in 2 to 4 days, although some cases may take 1 to 2 weeks or longer. Sex assignment depends on anatomy, functional prenatal and postnatal endocrinology, and the potential for sexual functioning and fertility, which may be independent of genetic sex. Until a sex assignment is made, gender-specific names or references should be withheld. The physician should examine the infant’s genitalia in the presence of the parents and then discuss with them the process of genital differentiation; that their child’s genitalia are incompletely or variably formed; and that further tests will be required before a decision can be made regarding the infant’s sex. Circumcision is contraindicated until a determination is made concerning the need for surgical reconstruction.

III. NORMAL SEXUAL DEVELOPMENT.

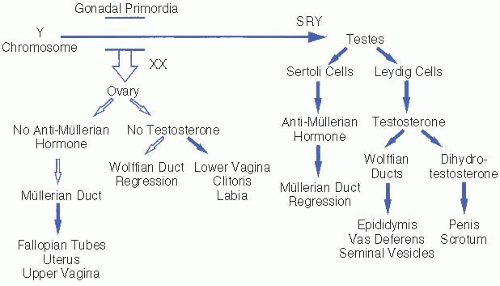

The process of gonadal and genital differentiation is depicted in

Figure 61.1. Sex determination progresses in stages. In general, early undifferentiated structures will develop down the normal female pathway by default, unless specific factors are present that direct differentiation down the male pathway.

Genetic sex is determined by the chromosomal complement of the zygote and the presence or absence of specific genes necessary for normal sexual development.

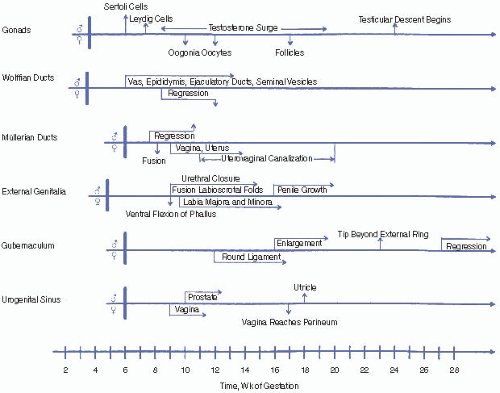

Gonadal sex. Undifferentiated gonads develop in the bilateral genital ridges around 6 weeks of gestation and begin to differentiate by 7 weeks. SRY, which encodes the primary testis-determining factor on the short arm of the Y chromosome, causes the undifferentiated gonads to develop into testes. Specific ovariandetermining genes have also been identified. Most 46,XX males and 46,XY females result from aberrant interchange between the X and Y chromosomes during paternal meiosis.

Phenotypic sex refers to the appearance of the genitalia. The fetal testis secretes two hormones critical for male genital formation: anti-müllerian hormone (AMH) is produced by Sertoli cells, and testosterone is produced by Leydig cells.

Internal genitalia. AMH causes regression of the müllerian ducts that would otherwise become the uterus, fallopian tubes, and upper vagina. Testosterone stabilizes the wolffian ducts and promotes their development into the vas deferens,

seminal vesicles, and epididymis. Müllerian duct regression and wolffian duct development require high

local concentrations of AMH and testosterone, respectively. Failure of a testis to develop on one side may result in ipsilateral retention of müllerian structures and regression of wolffian structures.

External genitalia. The enzyme 5α-reductase, present in high concentration in genital skin, converts testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT). DHT is the primary hormone responsible for masculinizing the external genitalia, including the genital tubercle and labioscrotal folds, which form the penis and scrotum, respectively. In the absence of DHT, these undifferentiated structures develop into the clitoris and labia. Testicular descent into the scrotum requires testosterone and generally occurs in the last 6 weeks of gestation.

Finally, formation of normal male internal and external genitalia under the influence of testosterone and DHT requires functional androgen receptors in the target tissues.

First trimester. Testicular synthesis of testosterone is stimulated by placental human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) due to its activation of the luteinizing hormone (LH) receptor. The first trimester is the only period during which the labioscrotal folds are susceptible to fusion. If a female fetus is exposed to excess androgens during the first trimester, her clitoris and labioscrotal folds will virilize and may appear indistinguishable from a normal male penis and scrotum, although the latter will be empty.

Second and third trimesters. Testicular androgens are stimulated by gonadotropins (primarily LH) from the fetal pituitary and are responsible for increase in penile size, scrotal maturation, and testicular descent. In a female fetus, exposure to excess androgens during the second or third trimester may lead to clitoral enlargement and darkening and rugation of the labioscrotal folds but not to labial fusion. Growth hormone also contributes to penile growth. High intrauterine concentrations of testosterone may influence brain development, possibly affecting later behavior and the formation of gender identity.

IV. NURSERY EVALUATION OF A NEWBORN WITH SUSPECTED DSD

A. History

Family history of CAH, hypospadias, cryptorchidism, infertility, pubertal delay, corrective genital surgery, genetic syndromes, or consanguinity.

Neonatal death. Death of a male sibling from vomiting or dehydration in early infancy may suggest undiagnosed CAH.

Maternal drug exposure during pregnancy, such as to androgens (e.g., testosterone, Danazol), antiandrogens (e.g., finasteride, spironolactone), estrogens, progestins, or antiseizure medications (e.g., phenytoin, trimethadione).

Maternal virilization during pregnancy due to maternal CAH, virilizing adrenal or ovarian tumor, or placental aromatase deficiency.

Placental insufficiency. First-trimester synthesis of testosterone in the fetal testis is dependent on placental hCG due to its activation of the LH receptor.

Prenatal findings suggesting associated conditions such as oligohydramnios or renal anomalies (genitourinary malformations) or skeletal abnormalities (campomelic dysplasia).

Physical examination

External genitalia. The examiner should note the stretched penile length, width of the corpora, engorgement, presence of chordee, position of the urethral orifice, presence of a vaginal opening, and pigmentation and symmetry of the scrotum or labioscrotal folds. The normal full-term male infant has a penile length of at least 2.5 cm, measured stretched from the pubic ramus to the tip of the glans (see

Fig. 61.3). The normal full-term female infant has a clitoris <1 cm in length. Posterior fusion of the labioscrotal folds is defined as an increased

anogenital ratio, which is the distance between the anus and the posterior fourchette divided by the distance between the anus and the base of the clitoris. An anogenital ratio >0.5 is indicative of first-trimester androgen exposure.

Gonadal size, position, and descent should be carefully noted. A gonad below the inguinal ligament is usually a testis, but an ovotestis or a uterus may present as an inguinal hernia. Abnormal genital development with clitoromegaly, or an apparently well-formed penis with an empty scrotum, should raise immediate concern that the infant is a female virilized by CAH.

Bimanual rectal examination may reveal müllerian structures (e.g., a cervix or uterus palpable in the midline).

Associated anomalies should be noted. Dysmorphic features suggest a more generalized disorder. Denys-Drash syndrome (Wilms tumor and nephropathy) or WAGR (Wilms tumor, Aniridia, Genitourinary anomalies, and mental Retardation) syndrome, both due to the mutations of

WT1 (11p13), can cause DSD in both 46,XY and 46,XX infants. Other conditions associated

with disorders of sex development include Smith-Lemli-Opitz, Robinow, and Goldenhar syndromes; campomelic dysplasia; and trisomy 13.

Diagnostic tests

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access