Chapter 28 Disorders of menstruation

Menstruation is normal if it occurs at intervals of 22–35 days (from day 1 of menstruation to the onset of the next menstrual period), as mentioned in Chapter 1; if the duration of the bleeding is less than 7 days; and if the menstrual blood loss is less than 80 mL. It was also noted that menstrual discharge consists of tissue fluid (20–40% of the total discharge), blood (50–80%), and fragments of the endometrium. However, to the woman menstrual discharge looks like blood and is so reported.

DEFINITIONS

AMENORRHOEA AND OLIGOMENORRHOEA

Primary amenorrhoea

In many cases, however, no abnormality is found and the young woman may be expected to menstruate in time. Some of these women have an eating disorder or exercise excessively. If an adolescent girl has not started menstruating by the age of 17, investigations should be made as described on page 321.

Secondary amenorrhoea

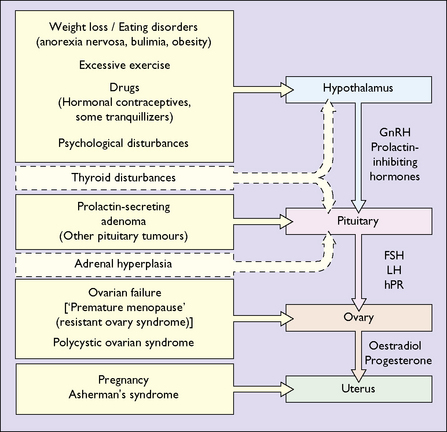

The most common cause of secondary amenorrhoea is pregnancy, but the condition may occur during the reproductive years for a variety of reasons. Figure 28.1 and Table 28.1 show the most common causes of amenorrhoea and their frequency. Only these causes will be discussed in this chapter.

Table 28.1 Causes of secondary amenorrhea

| Cause | Incidence (%) |

|---|---|

| Weight loss, low body weight, exercise | 20–40 |

| Polycystic ovarian syndrome | 15–30 |

| Pituitary insensitivity (post-pill) | 10–20 |

| Hyperprolactinaemia | 10–20 |

| Primary ovarian failure | 5–10 |

| Asherman’s syndrome | 1–2 |

| Hypothyroidism | 1–2 |

As noted in Chapter 1, normal menstruation depends on a normal uterus and vagina, and on the reciprocal interaction between hormones released from the hypothalamus (gonadotrophin-releasing hormones), the pituitary (the gonadotrophins – follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH)) and the ovaries (oestrogen and progesterone).

Investigation of secondary amenorrhoea

The purpose of the investigations is to exclude organic disease (for example a prolactin-secreting microadenoma or hypothyroidism) and to treat anovulation as a cause of infertility. If organic disease is not detected and infertility is not a problem, amenorrhoea does not represent a danger to the woman, but because low oestrogen levels may lead to bone loss, after 6 months of amenorrhoea hormone replacement treatment (see p. 325) should be advised.

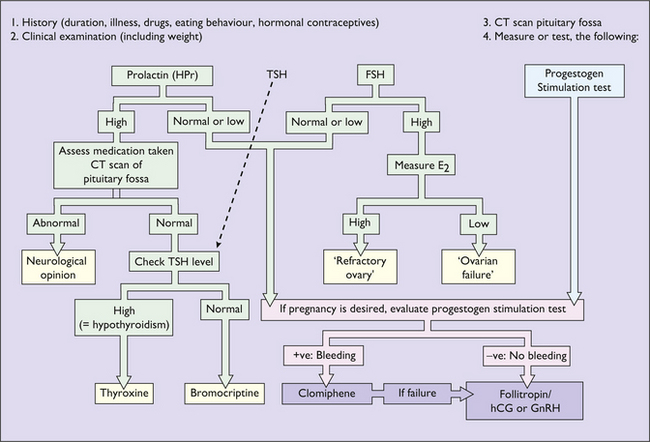

The sequence of investigations is shown in Figure 28.2.