Disorders of Arousal

Introduction

Parasomnias represent a broad group of sleep disorders that are defined as undesirable phenomena occurring predominantly during sleep, first described by Broughton.1 These sleep disorders are of great interest to sleep specialists, primary care providers, and patients (and their parents) because this group comprises some of the most common and bizarre sleep problems seen in children. Disorders of arousal are the most common of the parasomnias seen in children. Disorders of arousal are defined similarly by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-V)2 and the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd edition (ICSD-3).3 Both classification schema define subtypes: sleepwalking, confusional arousals and sleep terrors.

Clinical Description

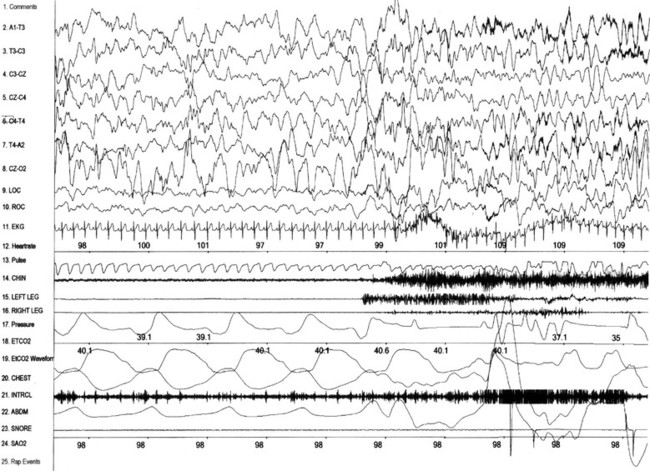

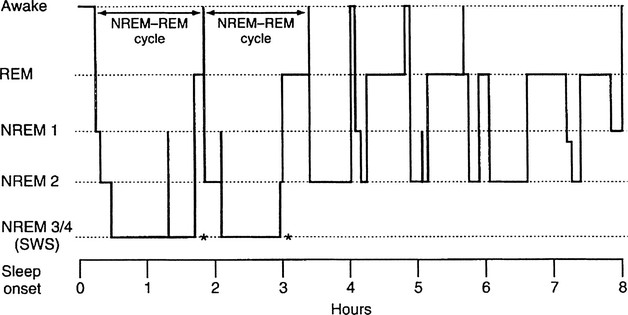

The clinical features common to most children experiencing any of the disorders of arousal include the timing during the nighttime sleep cycle, misperception of and unresponsiveness to the environment, automatic behavior, a high arousal threshold, varying levels of autonomic arousal, and (on waking after an event or in the morning) variable retrograde amnesia. The disorders of arousal typically begin abruptly at the transition from the first period of the deepest phase of non-REM (NREM) sleep (slow-wave sleep, stage N3) of the night (Figures 39.1 and 39.2), which accounts for the typical timing 60 to 90 minutes after sleep onset at the end of the first sleep cycle. The duration of each event can vary from less than 1 minute to over 30 minutes. In most cases, the arousal terminates with the child returning to sleep without ever fully awakening. Although only a single event usually occurs on a given night, some children may have multiple ones. When there are multiple events, they often will recur at 60- to 90-minute intervals during the night, corresponding to subsequent transitions out of slow-wave sleep at the end of each subsequent ultradian sleep cycle, though the arousals may occur at any time during the night. Successive events on the same night tend to be progressively milder.

Figure 39-1 Polysomnogram of a disorder of arousal that occurred precipitously out of slow-wave sleep(NREM 3).

Figure 39-2 Idealized sleep hypnogram showing ultradian rhythm through the night. NREM–REM cycles are approximately 90 minutes; the majority of SWS occurs early in the sleep period, and the majority of REM sleep occurs late in the sleep period. Disorders of arousal generally occur during the transition out of SWS (asterisks). NREM, non-REM; REM, rapid eye movement; SWS, short-wave sleep. Rosen GM, Ferber R, Mahowald MW: Evaluation of parasomnias in children. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am 1996;5:601–616.

Sleepwalking

Sleepwalking is common in children, as documented in two large, population-based studies by Klackenberg4 in Sweden, and Laberge and Petit5,6 in Quebec. Klackenberg studied a group of 212 randomly selected children in Stockholm, longitudinally from ages 6 to 16 years. The prevalence of quiet sleepwalking (occurring at least once during the 10-year data collection period in this group) was 40%. The yearly incidence varied from 6% to 17%, although only 3% had more than one episode per month. In Klackenberg’s study, the sleepwalking persisted for 5 years in 33% of children and for over 10 years in 12%.

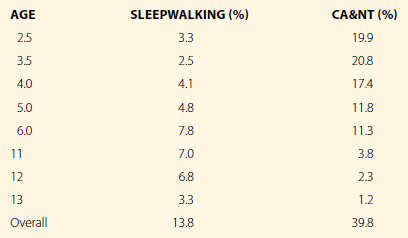

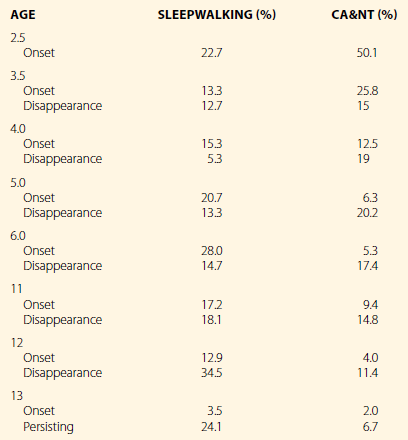

Laberge5 and Petit et al.6 studied 2675 randomly selected children in Quebec who were part of the Québec Longitudinal Study of Child Development conducted by the Québec Institute of Statistics . The parents completed a yearly sleep questionnaire regarding the presence of parasomnias in their children from 2.5 to 13 years of age. Occasional or frequent sleepwalking was present in 14% of the children at some time during that period. The yearly incidence of sleepwalking, as shown in Table 39.1, varied from 2.5% to 7.5%. Table 39.2 describes the ages of onset and offset of sleepwalking and confusional arousals/night terrors . In the majority of these children, the sleepwalking began and ended between the ages of 3 and 13 years. At 13 years of age 3% of the children were still sleepwalking. There was no gender difference in sleepwalking prevalence. In the studies of Laberge, Petit and Klackenburg, sleepwalking was frequently seen in those children who had confusional arousals at a younger age.

Table 39.1

Prevalence of Parasomnias at Various Ages in the Same Children

CA&NT, confusional arousals and night terrors.

Modified with permission from Laberge L, Tremblay RE, Vitaro F, Montplasir J: Development of parasomnias from childhood to early adolescence. Pediatrics 2000;106:67–74; Petit D, Touchette E, Tremblay R, Boivin M, Montplaisir J: Dysomnias and parasomnias in early childhood. Pediatrics 2007;119:e1016–1025.

Table 39.2

Age of Onset and Disappearance of Parasomnias at Various Ages in the Same Children

CA&NT, confusional arousals and night terrors.

Modified with permission from Laberge L, Tremblay RE, Vitaro F, Montplasir J: Development of parasomnias from childhood to early adolescence. Pediatrics 2000;106:67–74; Petit D, Touchette E, Tremblay R, Boivin M, Montplaisir J: Dysomnias and parasomnias in early childhood. Pediatrics 2007;119:e1016–1025.

Confusional Arousals/Sleep Terrors

In the studies of Laberge5 and Petit,6 there was no distinction between confusional arousals, sleep terrors, and night terrors. However, from the age distribution and the description of the events, the current nomenclature would characterize these as confusional arousals. In the Laberge and Petit studies, the prevalence of confusional arousals between the ages of 2.5 and 6 years was 39.8% (see Table 39.1). The yearly incidence was 19.9% at age 2.5 years, 11.3% at age 6 years, 3.8% at 11 years of age, and 1.2% at 13 years of age . In 85% of the children the confusional arousals first appeared between the ages of 3 and 10 years, and in the majority of these children, they disappeared before the age of 10 years (see Table 39.2). The confusional arousals persisted beyond 13 years of age in 6.7% of the children.

Pathophysiology of Disorders of Arousal

Disorders of arousal are best understood as a dissociated state during which elements of wakefulness, and NREM sleep occur simultaneously resulting in behavior that is neither fully awake or fully asleep. This concept, first put forward by Mahowald7,8 is consistent with the current understanding of sleep neurophysiology. During the disorders of arousal, some facets of wakefulness appear during the transition out of slow-wave sleep. This usually occurs at the end of the first sleep cycle. As a consequence, the transition out of slow-wave sleep, which is usually behaviorally inapparent, can be dramatic. The child appears caught between deep NREM sleep and wakefulness. The child’s behavior at this time has elements that we associate with wakefulness (walking, talking, crying, running) complex motor behaviors) and sleeping (misperception of and unresponsiveness to the environment, high arousal threshold, amnesia, automatic behavior) occurring simultaneously. The EEG during these arousals from sleep is typically characterized by a mixture of waking and sleeping rhythms with the simultaneous occurrence of alpha, theta, and delta frequencies, and suggests that different areas of the brain are in different states simultaneously. This dissociated state is inherently unstable, and eventually one state is fully declared. In most cases, the child appears to simply return to quiet sleep. Alternatively, the child may awaken totally but will have no recall of the arousal and will usually rapidly return to sleep.

The causes of the disorders of arousal are multifactorial. Genetic predisposition, homeostatic drive, sleep–wake cycling and synchronization, and behavioral and emotional states all seem to play some role in the clinical appearance of the disorders of arousal. Of these factors, genetic predisposition is probably the most important, though the mechanism is unknown. Sleep–wake cycling and synchronization are affected by age, homeostatic factors, circadian factors, hormones, and drugs. Affective disorders, anxiety, and environmental stress have all been identified as important factors in the appearance of the disorders of arousal in clinical studies,9,10 although the mechanisms by which these factors lead to the arousal is not known.

Genetics of Disorders of Arousal

A familial predisposition toward the disorders of arousal has been recognized since these disorders were first described. The genetics of the disorders of arousal has been explored by Hublin et al.11,12 and Nguyen et al.13 (in population-based twin studies) and also by Lecendreux.14 In Hublin’s retrospective study of adults the phenotypic variance of sleepwalking was attributable to genetic factors at 65%, which he believed was the result of many genes, each with minor effects. In Nguyen’s study, environmental information was gathered in an attempt to understand the relative contribution of genetic, shared environmental, and non-shared environmental factors leading to confusional arousals in children. They concluded that the best explanation was a two-component model with 44% of the variance explained by genetic factors and 56% of the variance explained by non-shared environmental factors. These results are consistent with the results of Lecendreux, who looked at human leukocyte antigens and sleepwalking. The familial predisposition to disorders of arousal may be secondary to the familial aggregation of restless leg syndrome or sleep-disordered breathing, which are recognized as triggers for disorders of arousal.18 A positive family history of a first-degree relative with a disorder of arousal is present in 60% of the children with a disorder of arousal compared with 30% in children without disorders of arousal.

Sleep Homeostasis and Disorders of Arousal

There is good theoretical support and some experimental evidence that the familial predisposition toward the disorders of arousal is mediated by the genetic control of the of the sleep homeostatic process. This process has been shown to be under strong genetic control in animal studies.16 Studies in mice have demonstrated that sleep loss leads to an increase in homeostatic drive, with a change in slow-wave sleep activity as measured by delta power, in a dose–response fashion that varies with the duration of prior wakefulness and is different in different genotypes. A quantitative trait–loci analysis revealed that this trait is the product of multiple genes. Human EEG studies have also shown that slow-wave sleep and EEG slow-wave activity are markers for measuring homeostatic drive.17–19 Increases in slow-wave sleep and slow-wave activity occur after sleep deprivation and decline after sleep. The synchronization of the homeostatic and circadian processes optimizes the quality of sleep and wakefulness. This interaction is described in a comprehensive article by Dijk and Lockley.18 Adequate sleep duration occurs only when the circadian and homeostatic systems are fully synchronized. The clinical implication of this observation is that a child with an irregular and/or chaotic sleep–wake schedule will simply not be able to have optimum synchronization of the homeostatic and circadian systems; this inevitably leads to sleep disruption and sleep deprivation, which may lead to a clinical event in a child who may be predisposed to the disorders of arousal.