Disorders Causing Airway Obstruction

INSPIRATORY AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION

Shean J. Aujla

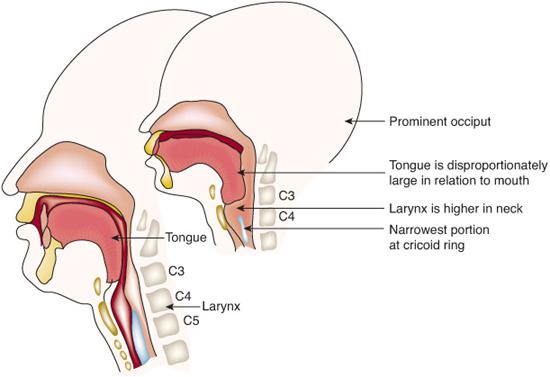

It is important to recognize the differences between the pediatric and adult upper airway to fully understand why even a relatively minor obstruction can cause significant airway compromise in children (Fig. 510-1). The pediatric airway is shorter and narrower and the larynx is placed more anterior than in adults.1 The narrowest portion of the pediatric airway is the subglottis, which is below the vocal cords. Therefore, mild edema in this region can result in a large reduction in the cross-sectional area of the airway. The resistance is inversely proportional to the fourth power of the radius of the airway (see Chapter 503). Therefore, even a small decrease in airway diameter leads to a much larger increase in resistance. Young children, and infants especially, have a large tongue in relation to the small oropharynx.1 They also have a larger epiglottis.1 Signs of partial inspiratory obstruction include stridor (a high-pitched sound heard on inhalation), hoarseness, and increased work of breathing (suprasternal and intercostal retractions).2 Stridor can be inspiratory or expiratory, depending on whether the obstruction is supraglottic or subglottic respectively. If the obstruction is severe or near-complete, worsening agitation, cyanosis, and respiratory failure will likely occur. Although acute stridor is usually infectious in etiology, other disorders may be present, especially when symptoms are severe or persistent. This chapter discusses inspiratory airway obstruction of infectious or noninfectious origin.

FIGURE 510-1. Differences between the adult (left) and pediatric (right) upper airway. (Finucane BT: Principles of Airway Management. Philadelphia, FA Davis, 1988.)

NONINFECTIOUS CAUSES OF UPPER AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION

LARYNGEAL ANOMALIES

LARYNGEAL ANOMALIES

Disorders of the upper airway are also discussed in Chapter 371.

Laryngomalacia is the most common cause of noninfectious, persistent stridor in infants. It is characterized by a long, curved epiglottis that folds into an omega shape, with varying degrees of prolapse of the arytenoids during inspiration.3 The inspiratory noise can begin in the first 2 months after birth, and it commonly presents as stridor that worsens with crying and activity; improvement occurs when the infant is placed in the prone position. Diagnosis is usually based on the history and physical examination; however, airway endoscopy is also helpful. The condition usually resolves spontaneously by 12 to 24 months. In more severe cases, surgery (supraglottoplasty) may be necessary.4 Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), has been linked to laryngomalacia, and the possibility of concurrent reflux should be considered and treated.5

Laryngeal cysts, webs, laryngoceles, and saccular cysts are much less common conditions that can cause airway obstruction.4 Laryngeal cysts can present with hoarseness and stridor. Saccular cysts are caused by obstruction of the laryngeal saccule opening.4 Diagnosis is made via airway endoscopy, and treatment requires marsupialization or surgical excision. Laryngoceles are another abnormality of the laryngeal saccule. Laryngeal webs are rare congenital anomalies that can present in the newborn period if the web is large and cause significant respiratory distress and stridor. Treatment includes surgical approaches such as laryngotracheal reconstruction.

SUBGLOTTIC LESIONS

SUBGLOTTIC LESIONS

Congenital subglottic stenosis consists of narrowing of the airway lumen at the cricoid region, not thought to be secondary to intubation, trauma, or other acquired causes.4 Depending on the severity, it is commonly diagnosed in the first few months of life. Common presentations include inspiratory or biphasic stridor (stridor that is both inspiratory and expiratory) and recurrent croup. Airway endoscopy is necessary to evaluate the severity of the stenosis and confirm the diagnosis. Surgical intervention may be necessary for extremely severe cases, but in most children, the symptoms improve as the larynx grows.4

Subglottic hemangiomas (congenital vascular lesions) are rare but can be life threatening because of their location and size. Symptoms can include recurrent croup, stridor, hoarseness, and cough. Half of these children will also have hemangiomas on their skin.4 Infants will often present prior to 6 months of age, and females are more commonly affected. Diagnosis is confirmed by rigid airway endoscopy.2 Corticosteroids are helpful in some, but not all, to hasten regression of the lesion; however, they are not without several side effects.  Surgical resection may be required for large lesions.4

Surgical resection may be required for large lesions.4

TUMORS OF THE UPPER AIRWAY

TUMORS OF THE UPPER AIRWAY

Mass lesions and tumors of the upper airway are rare in childhood. Malignancies that affect the head and neck (including the oropharynx) include non-Hodgkin lymphoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, and teratoma.2 Management is specific to the tumor type and may include a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy.2

GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE

GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE

GERD is associated with or can exacerbate several upper respiratory conditions, including apnea, laryngospasm, spasmodic croup, hoarseness, throat clearing, chronic cough, and stridor.5 Reflux of gastric contents into the laryngopharyngeal region can lead to chronic inflammation and edema. GERD often occurs in conjunction with laryngomalacia, and stridor may improve with antireflux medication.5 Apneic episodes in infants should be investigated for the possibility that re-flux has a role.5 Animal models have shown that GERD, along with trauma and infection, can lead to subglottic stenosis, and studies in children suggest at least an association between GERD and subglottic stenosis.5 No studies have proven a response to aggressive acid inhibitory therapy but this is often prescribed. Diagnostic testing for GERD may include a pH probe, gastric scintiscan, and esophageal biopsy6 as well as management, are discussed in Chapters 394 and 511.

VOCAL CORD ABNORMALITIES

VOCAL CORD ABNORMALITIES

Vocal Cord Dysfunction

Vocal cord dysfunction (VCD), also known as paradoxical vocal fold motion (PVFM), has gained recognition recently as a cause of upper airway obstruction as a result of paradoxical closure of the true vocal folds during inspiration.7 It is most commonly seen in females and historically was thought to be related only to psychiatric or psychogenic disorders.7 This has since been shown not to be the case. VCD can occur over wide range of ages from childhood to adulthood; however, in children, it usually presents in early adolescence.8 A wide spectrum of symptoms can occur, including throat tightness, chest tightness and pain, hoarseness, difficulty getting air “in,” cough, inspiratory stridor, dysphonia, dyspnea, and air hunger.7,8 Patients may experience anxiety and panic during these acute episodes. Triggers are numerous, including emotional stressors, reflux, and exercise.7 Asthma and GERD exist as comorbid conditions with VCD and should be considered and treated if necessary. VCD may be mismanaged, with a false diagnosis of asthma, and patients are placed on unnecessary medications such as corticosteroids. Exposure to irritants, such as cleaning solutions, perfumes, or chlorine in swimming pools has also been associated with VCD.7 Careful history and physical examination, spirometry with inspiratory loops, and documentation of normal oxygen saturation during episodes are the keys to diagnosis of VCD.7,8 Spirometry may reveal attenuation of inspiratory flow, indicating extrathoracic airway obstruction, whereas asthma causes intrathoracic airway obstruction. Laryngoscopy after exercise challenge can also document paradoxical vocal cord motion in those patients whose symptoms are related to activity. Treatment of VCD is best carried out via a multidisciplinary approach. It involves the patient’s physician as well as a speech therapist who can focus on breathing exercises.8 Patient education and their understanding of the condition are also extremely important.

Vocal Cord Paralysis

Causes of vocal fold paralysis are further discussed in Chapter 371 and are shown in Table 371-5. Neonates can present with stridor caused by unilateral (often with a hoarse cry) or bilateral (often with a normal or high-pitched cry) vocal cord paralysis. This can be secondary to birth trauma, neurological disease, or following heart or thoracic surgery (eg, patent ductus arteriosus surgery), and it can also be idiopathic.2 Congenital vocal cord paralysis usually presents in the first month of life, and the possibility of other congenital anomalies should be investigated. Central neurologic disease, such as brainstem compression with an Arnold-Chiari malformation, can cause bilateral vocal cord paralysis.2 Airway obstruction, apnea, and cyanosis are more severe with bilateral paralysis, and many of these infants need tracheotomy. Diagnosis is confirmed with airway endoscopy to observe the motion and position of the vocal cords. Over time, paralysis may resolve spontaneously, but until then, the infant is at risk for aspiration with feeding.2 A modified barium swallow with a feeding evaluation is helpful in assessing aspiration and swallowing problems in these patients. Surgical intervention, such as arytenoidectomy, may also be necessary.

Recurrent Respiratory Papillomatosis

Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP), caused by human papilloma virus (HPV), commonly affects the vocal folds. HPV types 6 and 11 may cause these lesions, but HPV type 11 causes more aggressive disease in children.9 Patients can present with hoarseness, dysphagia, a weak or hoarse cry, and with advanced lesions, stridor, and shortness of breath. The virus can be transmitted to the infant from the mother with genital HPV infection during vaginal delivery. Risk factors for the juvenile onset of RRP include being the firstborn child, being born by vaginal delivery, and being born to a teenage mother.9 Evaluation includes history and physical examination, followed by nasopharyngolaryngoscopy or direct laryngoscopy for visualization. The diagnosis is made on gross appearance of the lesions as well as pathology.9 Treatment includes surgical therapies such as carbon dioxide laser ablation, pulsed dye laser ablation, as well as adjuvant treatments such as cidofovir and α-interferon.9 Unfortunately, papillomas commonly recur, and some patients require multiple procedures over their lifetime. There is a very low risk of malignant transformation, but progression to squamous cell carcinoma has been reported.2

FOREIGN BODIES IN THE THROAT

FOREIGN BODIES IN THE THROAT

Foreign body aspiration is discussed in detail in Chapter 118. Foreign bodies may lodge just below the vocal cords or in the upper esophagus and produce symptoms similar to croup or asthma. There is often not a witnessed choking episode or clear history of foreign body aspiration. Physicians should have a high suspicion (of foreign body) in a toddler, for example, who presents with sudden onset of stridor, cough, and hoarseness without other signs of an upper respiratory tract infection (such as fever, rhinorrhea, or other viral prodrome). Common foreign bodies include seeds, bones, coins, and pieces of plastic.10

Upper airway and chest radiography is recommended when there is an abrupt onset of symptoms of upper airway obstruction. Radiography of the neck/upper airway can be helpful if the inhaled object is radiopaque (coins, batteries) but not if the object is radiolucent.11 Endoscopic inspection and removal of the foreign body in the upper airway is performed by otolaryngology.

BURN INJURY

BURN INJURY

Airway management is the first concern in a child who has sustained a burn injury. Scald burns can affect the airway if there is significant face and/or neck involvement. Inhalation injuries should be considered after a child has been exposed to a flame injury, especially in a closed space.12 Clinical signs include singed nasal or facial hairs, stridor, wheezing, respiratory distress, hoarseness, oral blisters, as well as edema and blisters of the tongue.12 Flexible bronchoscopy can be used to evaluate the extent of airway involvement. Smoke inhalation can also lead to acute lung injury, affecting lung parenchyma and also result in carbon monoxide intoxication.12 Endotracheal intubation in the acute setting may be necessary, since worsening airway edema may progress rapidly and complicate airway management.12 Management includes obtaining appropriate control of the airway, fluid resuscitation, and other supportive measures of care.12

ANGIOEDEMA AND ANGIONEUROTIC EDEMA

ANGIOEDEMA AND ANGIONEUROTIC EDEMA

Angioedema and hereditary angioedema are discussed further in Chapters 189 and 193. Angioedema consists of localized swelling that is distinct from urticaria, which can occur to several triggers, and most commonly is seen in vascular areas of the body such as the face, eyes, mouth, and oropharynx. Angioedema occurs in tissues deeper than the dermis and lasts for 24 to 48 hours, while urticaria occurs in the dermis and usually lasts for shorter periods.13 Both entities can coexist in patients. Angioedema can be allergic and can be seen with anaphylaxis (immunoglobulin E [IgE] mediated to foods, insects, or certain medications). It can also be nonallergic, such as is seen when angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and aspirin cause angioedema (non-IgE mediated).13 It can occur in autoimmune and lymphoproliferative diseases as well as in trauma and certain infections. It can affect the upper airway, causing obstruction with symptoms of stridor and respiratory distress. Acute management involves use of subcutaneous epinephrine and airway control as necessary. Antihistamines and steroids may be necessary for long-term management.

Hereditary angioneurotic edema is a disorder secondary to low levels of, or defective, C1 inhibitor,14 a protein that inactivates targets (such as C1 esterase) specifically in the complement system as well as in the clotting and kinin pathways. Unchecked activation of these mediators leads to edema formation (via vascular permeability). It is inherited via an autosomal dominant pattern, although there have been cases of de novo mutations in patients whose parents do not have hereditary angioneurotic edema.14 The clinical manifestations are subcutaneous edema, abdominal/intestinal edema, and laryngeal edema. Episodes of larynx edema are rare but extremely concerning because of its serious consequences. Symptoms include stridor, hoarseness, a feeling that something is stuck in the throat (globus sensation), and respiratory distress.14 Acute management includes control of the airway with intubation if necessary and replacement with intravenous C1-inhibitor concentrate. Prophylactic, long-term treatment involves avoiding known triggers and using antifibrinolytics and attenuated androgens.14

AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION IN CHILDREN WITH DOWN SYNDROME

AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION IN CHILDREN WITH DOWN SYNDROME

Children with Down syndrome are particularly at risk for upper airway obstruction secondary to anatomical abnormalities in addition to hypotonia. They have macroglossia and midface hypoplasia combined with a softer supraglottis.15 As a result, there is a higher prevalence of laryngomalacia in these infants.16 GERD is commonly seen alongside laryngomalacia. Obstructive sleep apnea has been found more frequently in children with Down syndrome than in the general population.15 This is also secondary to hypotonia, mandibular hypoplasia, and large adenoids, which all lead to collapse of the upper airway at inspiration while asleep.

AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION IN CHILDREN WITH CHARGE SYNDROME

AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION IN CHILDREN WITH CHARGE SYNDROME

CHARGE syndrome represents the following associated malformations: C, coloboma; H, heart defects; A, atresia of choanae; R, retardation of growth and/or development; G, genital anomalies; and E, ear abnormalities.17 It is extremely common for these infants to suffer from laryngopharyngeal airway obstruction, and some require tracheotomy.17 Studies have shown that contributing factors include laryngomalacia and supraglottic obstruction due to hypotonia of this region. Infants with CHARGE syndrome can also have swallowing problems and general laryngeal dyscoordination due to cranial neuropathies (cranial nerves VII, IX, X).17 There tends to be a high frequency of GERD in these infants.

INFECTIOUS CAUSES OF UPPER AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION

CROUP (LARYNGOTRACHEOBRONCHITIS)

CROUP (LARYNGOTRACHEOBRONCHITIS)

Croup is the most common infectious cause of acute stridor and upper airway obstruction seen in children (see also Chapter 241).18 It is seen in the early fall and winter months, when viral upper respiratory tract infections reach their peak. The age group most frequently affected is between 6 months and 4 years of age, and it is seen in males more than in females.18 Several viruses can cause croup; however, parainfluenza type I is the most common organism. Parainfluenza types II and III, respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, and influenza can also cause croup. Mycoplasma pneumoniae has also been implicated in croup.19 Many children have a 1- to 3-day history of viral prodrome consisting of nasal symptoms such as congestion or rhinorrhea and possibly fever.20 Subsequently, there is development of a harsh, barky cough that is often described to be similar to “a barking seal or dog.” They may also have inspiratory stridor as well as respiratory distress indicated by nasal flaring and suprasternal and subcostal retractions. Stridor is often worsened with activity, crying, and increased anxiety or agitation. Typically, the course of illness lasts for no more than 1 week.18 The viral infection causes inflammation and edema of the airway, especially in the subglottic region.20 Croup is diagnosed clinically by history and physical examination.18 An x-ray of the upper airway can be useful to distinguish croup from other entities such as a retropharyngeal abscess or foreign body. In croup, a “steeple sign,” which is the tapering of the subglottic airway, may be seen, but many patients will also have normal x-rays.19 The differential diagnosis of croup includes retropharyngeal abscess, epiglottis, foreign body, angioedema, and structural abnormalities such as laryngomalacia or subglottic stenosis. Obtaining a thorough and careful history greatly helps to differentiate croup from these other conditions. Children who have recurrent croup should be investigated for other problems beyond simply recurring viral infections, such as anatomic abnormalities or GERD.

Most children with croup do not require hospitalization; however, many will need to be evaluated in an acute care setting if they are having worsening stridor and respiratory distress. Some physicians continue to recommend treatments such as mist therapy (air humidification), but current studies available do not show evidence that this is effective.20 Exposing children to steam from hot showers or baths at home can put them at risk for scald injuries.20 Fever reduction and avoidance of agitation are useful, both at home and in the hospital setting. Obtaining blood work such as blood gas measurements is rarely necessary and can certainly lead to further agitation, increasing a child’s stridor and dyspnea. Oxygenation should be monitored by pulse oximetry.

Corticosteroids continue to be one mainstay of therapy, even for more mild cases of croup. Dexamethasone, either oral or intramuscular, is effective in decreasing symptom severity, decreasing hospitalization rates, and increasing symptom resolution.1819 The standard use of dexamethasone is a 1-time dose of 0.6 mg/kg; however, smaller doses have been shown to be effective.20 Prednisolone has also been shown to be efficacious compared with placebo for treatment of croup, as is nebulized budesonide at a dose of 2 mg.1819 Nebulized racemic epinephrine is often used to acutely relieve upper airway obstruction by decreasing edema via vasoconstriction and possibly preventing further progression and need for intubation.18 It will not alter the course of the illness as corticosteroids do. It is classically used in patients with more moderate to severe croup. Heliox, which is a helium and oxygen mixture (eg, 80:20) and therefore a gas of much lower density than air (but similar viscosity to air), can improve air flow in severe croup (as well as in asthma and bronchiolitis).20 It is used when a child is in severe respiratory distress and there is concern of potential respiratory failure.

SPASMODIC CROUP

SPASMODIC CROUP

Spasmodic croup consists of episodes of inspira-tory stridor that occur mostly at night, without the classic viral prodrome.21 The child may have had symptoms of a mild upper respiratory infection, but fever is usually absent. The symptoms present quite suddenly, in a well appearing child. Children are older than those who have viral croup, and their symptoms usually resolve within 24 to 48 hours.20 The child awakens with a barking, harsh cough and inspiratory stridor. Many will have recurrent episodes. The etiology is not completely known, but both viral illness and atopic disease is associated with spasmodic croup.20 Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) has also been associated with recurrent croup.21 Parents can attempt supportive care at home, such as exposure to cool night air to improve symptoms. Treatment with racemic epinephrine and steroids is helpful, as in viral croup. If symptoms are frequent and recurrent, structural abnormalities of the airway should also be considered.

ACUTE EPIGLOTTITIS

ACUTE EPIGLOTTITIS

Acute epiglottitis (also known as supraglottitis) is an infection leading to inflammation and swelling of the epiglottis, which can progress quickly to becoming a life-threatening emergency (see also Chapters 240, 241). Prior to the standard use of Haemophilus influenzae b (Hib) vaccine, this organism was the most common cause of epiglottitis. Currently, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and group A β-hemolytic streptococci are among the most common pathogens that cause this infection.19 It is now rarely seen in childhood but must be considered when an ill-appearing child presents with acute-onset of stridor. There have still been cases of epiglottitis caused by Hib in immunized children, indicating the possibility of vaccination failure.19 Children affected are usually between 2 and 8 years old, although most recently the age appears to be increasing. It presents quite suddenly (over 6–24 hours) with high fever, irritability, throat pain, stridor, and what is known as a “hot potato” or muffled voice.18 Unlike croup, there is usually no preceding viral prodrome or cough, and the child has an extremely ill appearance. The child will prefer to sit in the “tripod” position, leaning forward and extending the neck to open the airway and increase air entry.18 Eventually it becomes hard for the patient to handle secretions and saliva, and therefore drooling will occur.18 Cyanosis, stridor, and drooling all point to advanced, severe airway swelling and impending respiratory failure due to airway obstruction.

Airway management is the first priority if epiglottitis is suspected. Therefore, obtaining blood work and aggressive attempts at visualization of the oropharynx should be avoided. Only in a child who appears stable should a cautious examination of the posterior pharynx (without the use of a tongue depressor) be attempted.18 Manipulating or touching the oropharynx with a tongue depressor can cause complete obstruction. The examination may reveal a grossly swollen, erythematous epiglottis, projecting beyond the base of the tongue.18 A definitive diagnosis of epiglottitis should occur in a controlled situation (such as the operating room) with appropriate personnel (anesthesiologist and otolaryngologist) who are trained to manage difficult airways and are able to secure the airway surgically if necessary. A lateral neck radiograph can be helpful but should not delay treatment. A “thumbprint sign,” which describes a round and thickened epiglottis, can be seen on the x-ray.19 Once the child has a secured airway and is out of danger of progressing to total airway obstruction, a complete blood count (CBC) and blood culture can be done and intravenous antibiotics can be started. Patients will often have positive blood cultures. High-dose, broad-spectrum antibiotics such as ceftriaxone or ampicillin-sulbactam should be used.1819 Complications seen with epiglottitis can include complete airway obstruction, pulmonary edema postintubation, pulmonary infiltrates and pneumonia, and respiratory arrest.18

BACTERIAL TRACHEITIS (PSEUDOMEMBRANOUS CROUP OR BACTERIAL CROUP)

BACTERIAL TRACHEITIS (PSEUDOMEMBRANOUS CROUP OR BACTERIAL CROUP)

Bacterial tracheitis is an uncommon entity but an important cause of severe upper airway obstruction. It is commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus; however, Moraxella catarrhalis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and H influenzae are also seen (see also Chapter 240).18 Children present with symptoms similar to epiglottitis and croup. After this initial presentation, they can progress to having respiratory distress with high fever and become very ill appearing. Lateral neck radiographs can show subglottic narrowing (steeple sign, as can be seen in viral croup) and irregularity of the tracheal air column (indicating sloughing of pseudomembranous material from the tracheal wall).18 They can also develop pulmonary infiltrates consistent with pneumonia. Airway endoscopy reveals large amounts of mucopurulent secretions and subglottic edema. These secretions are thick and can occlude the airway. They should be suctioned and sent for Gram stain and culture. Treatment includes appropriate intravenous antibiotics as well as airway management such as endotracheal intubation if necessary.18

RETROPHARYNGEAL AND PERITONSILLAR ABSCESS

RETROPHARYNGEAL AND PERITONSILLAR ABSCESS

The retropharyngeal space refers to the area between the anterior cervical vertebrae and the posterior pharyngeal region.2 A retropharyngeal abscess occurs in this space either by spread of an upper respiratory tract infection (such as pharyngitis) to the retropharyngeal lymph nodes or by a penetrating oropharyngeal injury. Group A Streptococcus, anaerobic organisms, and Staphylococcus aureus commonly cause this disease.18 This infection is not common, but it needs to be diagnosed correctly and treated without delay. It is mostly seen in children under 6 years of age, especially in toddlers. This is explained by the fact that the lymphatics that drain the retropharyngeal space atrophy by this age.19 Clinical presentation includes fever, dysphagia, drooling, neck stiffness, and pain. As the infection progresses and pus collects, forming the abscess, stridor and respiratory distress can develop from compression of the pharynx. The differential diagnosis includes meningitis, epiglottitis, and croup. Physical examination can reveal bulging of the posterior wall of the pharynx. Obtaining a lateral neck radiograph is helpful in these cases in order to specifically examine the retropharyngeal space for soft tissue swelling. Widening of this potential space (> 7 mm at the level of the second cervical vertebrae) may indicate a retropharyngeal abnormality.18 Computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck is necessary to distinguish between a true abscess and cellulitis and is often used in evaluation of this deep neck infection.18 Treatment requires the use of appropriate intravenous antibiotics; however, surgical drainage is performed in those cases in which medical management fails. Complications can include respiratory failure, aspiration pneumonia (from abscess rupture), and spread of infection to other areas in the deep neck.19

Peritonsillar infections and abscesses occur as a result of spread from an infection in the tonsils. They are most common in adolescents who have recurrent tonsillitis.19 Fever, throat pain, decreased oral intake, and drooling are some of the symptoms seen. Both anaerobic and aerobic organisms cause this infection. Physical examination can reveal displacement of the uvula.19 CT scan is often used to aid in the diagnosis of abscess.19 Treatment includes intravenous antibiotics and may include surgical drainage. Airway obstruction is a potential complication of peritonsillar abscess.19

EXPIRATORY AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION

Jonathan E. Spahr

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree