Differential and Management of Limb Anomalies

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT OF THE FLAIL UPPER EXTREMITY

The differential diagnosis for a flail, or nonmoving, upper extremity is fairly short and includes neonatal brachial plexus palsy (NBPP), fracture, distal humeral transphyseal separation, and bone or joint infection. The history and physical are usually adequate to make the diagnosis, although imaging and laboratory examinations can help.

Clinical Findings

History should focus on the infant’s delivery and perinatal events. Both brachial plexus palsy and fractures sustained during birth are associated with difficult deliveries, shoulder dystocia, and larger infants; it is important to remember that a patient may have a fracture concomitant with a brachial plexus palsy. For both NBPP and fracture, the lack of movement will have been present since birth as opposed to a patient with infection, who likely had a period, however short, of normal movement of the limb with subsequent pseudoparalysis developing over time. If an infant sustained a fracture after the neonatal period, he or she will also have had a period of normal movement of the limb. Infections may be characterized by increased fussiness or other general manifestations of malaise, but frequently the pseudoparalytic limb may be the only finding.

The physical examination should focus on inspection for any erythema or swelling, which can be seen not only in infection but also in fractures and transphyseal separations, and palpation for any crepitus, which would suggest fracture. Pain with palpation or movement of the limb would be seen in fracture, transphyseal separation, and infection but not in NBPP. In addition, reflex testing should be done. Because fractures, transphyseal separations, and infections are painful, the lack of movement of the limb is because of pain inhibition rather than true paralysis. Therefore, on physical examination, any movement with reflex testing (eg, Moro) is supportive of infection or fracture; patients with NBPP will have no movement, even with reflex testing, because of a true paralysis of the limb. Occasionally, patients with arthrogryposis that affects the upper extremities preferentially will have a similar “waiter’s tip” appearance as NBPP; the difference will be that, early on, patients with brachial plexus palsy will have normal passive range of motion, whereas arthrogrypotic patients will be stiff from the very beginning. In addition, NBPP is almost universally unilateral, whereas arthrogryposis will affect both upper extremities, although involvement may be asymmetric.

Confirmatory Tests

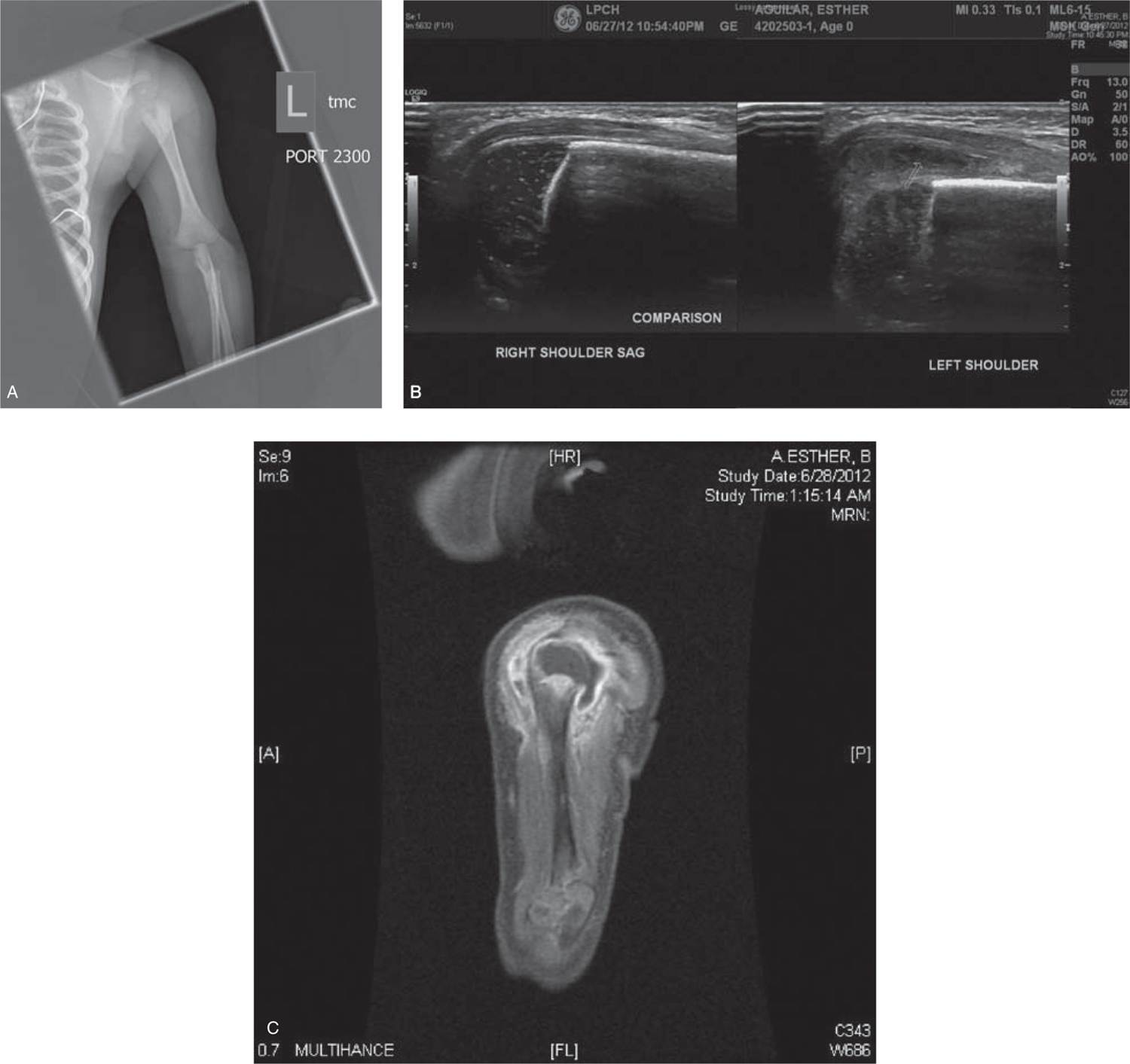

In brachial plexus palsy, x-ray and ultrasound evaluations will be negative (unless the infant has an associated fracture) and are not routinely ordered because the diagnosis can usually be made by history and physical alone. However, imaging, including x-rays and ultrasound, can be helpful in distinguishing between trauma (fracture or transphyseal separation) and infection. Evaluation should include x-rays of the clavicle and arm; fractures will most likely be of the clavicle or humeral shaft. If the elbow looks dislocated on x-ray, it is most likely a transphyseal separation; in a neonate, the elbow joint is completely cartilaginous and therefore difficult to see on plain x-ray. True elbow dislocations do not really occur in neonates, but fractures through the growth plate of the distal humerus, or transphyseal separations, do. The displacement of the nonossified epiphysis will look like a dislocation on x-ray; the diagnosis can be made based on the knowledge that transphyseal separation is much more likely than an elbow dislocation and can be confirmed by ultrasonography, which will show the normally articulated joint but separated physis. X-ray findings may be absent or variable in infections; joints, especially the shoulder (or the hip in the lower extremity), may appear subluxed because of a purulent fluid collection. In addition, if the infection has been present long enough, bony changes from ongoing osteomyelitis may be seen (Figure 120-1). Ultrasound can be helpful to evaluate for any joint effusion, which would be suggestive of infection; occasionally, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used to fully characterize the extent of the infection. It is not routinely used to make the diagnosis in a flail extremity. Laboratory studies are not routinely helpful in ruling out an infection because white blood cell counts and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) can be unreliable in neonates.1 The C-reactive protein (CRP) value is more helpful; if it is normal, it has a 95% negative predictive value for infection.2 All laboratory values should be normal in NBPP, fracture, and transphyseal separation; however, they may also be normal in neonatal infection.

FIGURE 120-1 A, Anteroposterior x-ray of left shoulder in 3-week-old with 2-day history of decreased movement of left arm; B, ultrasound of affected and unaffected side demonstrating fluid collection concerning for septic arthritis; C, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirming septic arthritis and associated osteomyelitis.

Treatment

Treatment depends on the cause of the flail extremity. If the patient is diagnosed with brachial plexus palsy based on history and physical examination, initial treatment is stretching of the arm, which begins usually 1 week after birth; the goal is maintenance of range of motion while the patient’s neurologic function recovers. Fracture and transphyseal separation treatment is usually supportive. Given the almost-infinite bony remodeling capability of the neonate, fractures usually do not need to be reduced or realigned as any angulation will resolve over time. It is incredibly difficult to splint or cast the upper extremity of a neonate—immobilization to make the infant more comfortable can be achieved with pinning the sleeve to the shirt or with a custom-made stockinette sling. Fractures and transphyseal separations heal incredibly rapidly in infants, and usually patients are asymptomatic within 2–3 weeks of a clavicular or humeral shaft fracture. Treatment of osteomyelitis or septic arthritis varies widely, and the details that go into decision making are beyond the scope of this chapter. In general, however, osteomyelitis is more frequently initially treated with antibiotics; septic arthritis may more commonly be treated with surgery because of the chondrotoxicity associated with bacterial joint infections. It is important to remember that many physes are intra-articular in neonates, so osteomyelitis can rapidly spread to an adjoining joint. A high index of suspicion is required when evaluating and treating bone and joint infections in neonates.

Follow-up

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree