Diagnostic Imaging in Abnormal Placentation

Kimberly Vickers

Erin H. Burnett

INTRODUCTION AND RESEARCH

Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) and abnormally invasive placenta (AIP) are the general terms used for placenta accreta. The varying forms of placenta accreta (Figure 5-1) range from a mild form known as accreta, to a more invasive form known as increta, and finally to the most invasive form known as percreta.1 Accreta occurs when the placental villi attach to the myometrium rather than the decidua. In placenta increta, the villi penetrate into the myometrium. Percreta is characterized by chorionic villi attaching through the myometrium and possibly to adjacent structures. The most common site of attachment is the bladder. It may also attach to the rectum and occasionally to the bowel, although this is rare.

Two studies conducted in 1997 and 2005 included a total of 138 histologically confirmed abnormally implanted placentas. Based on the hysterectomy specimens, the types and frequency were accreta 79%, increta 14%, and percreta 7% (Figure 5-1).1,2,3

The exact pathogenesis for placenta accreta is not exactly known, but it is largely believed that many of the cases are a result of postoperative scarring. Theories for this have been supported by the observations that 80% of cases were associated with a history of previous cesarean delivery, curettage, and/or myomectomy.4 The most common theories for the pathogenesis are related to abnormal vascularization resulting from the scarring process following surgery. Localized hypoxia in this scarred area may lead to both defective decidualization and excessive trophoblastic invasion. As a result, the placenta attaches directly to the myometrium.

In cases of partial or complete dehiscence of the uterine scar, the extravillous trophoblasts have access to the deeper parts of the myometrium, bladder serosa, and potentially beyond resulting in increta and percreta.

INCIDENCE

The incidence of PAS has increased significantly through the years. In the 1950s, abnormal placental attachment was 1 in 30,000 deliveries in the United States and only 1 in 10,000 deliveries in the 1960s. The current overall incidence of placenta accreta is 3 in 1000 deliveries. There has been a considerable increase over the past several decades, mainly due to the increased numbers of cesarean deliveries and multiple repeat cesareans.

FIGURE 5-1 Types of placentation. A, Normal placentation. B, Accreta. C, Increta. D, Percreta.1 |

The rates of cesarean deliveries in the United States have increased from 2% in the 1950s to 5.8% in the 1970s. The rate from 2017 in the United States ranges from 22.5% to 37.8% across the country based on numbers from the National Center for Health Statistics.5

The rates of cesarean section vary widely per country. In 2016, the World Health Organization addressed the high rates of cesarean sections in Greece stating that over half of the deliveries in that country are by cesarean. This is between 50% and 70% with a large rate disparity between the public and private hospitals.6 In Brazil, the cesarean rate is 55.6%. The country is currently trying to reverse the growing numbers. The United States is also trying to reduce the number of cesarean sections. The lowest rate of elective cesarean deliveries is in Finland with a rate of 6.6%, which is well below the World Health Organization’s recommendation of 10% to 15%.7

ASSESSING FOR ABNORMAL PLACENTATION

Assessing for abnormally adherent placenta is similar to putting the pieces of a puzzle together. Assessment requires thorough medical history, maternal serum screening, and ultrasound. If the ultrasound shows sign of accreta, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be considered as a possible adjunctive tool, although, no single modality determines accreta with 100% accuracy. The final diagnosis of accreta is based on the results of a histology of specimen (Figures 5-2, 5-3 and 5-4).

RISK FACTORS FOR PAS AND SCREENING TO PREDICT WHO MAY BE AT RISK

A multitude of risk factors for accreta exist. Thorough documentation of all factors is important.

The biggest risk factor is a history of uterine surgery, to include but not limited to, cesarean section, myomectomy, intrauterine adhesion removal, dilation and curettage, ectopic pregnancy, cornual resection, and endometrial ablation.

Other risk factors include pelvic irradiation, advanced maternal age, Asherman syndrome, grand multiparity, hypertensive disorders, and smoking.

In vitro fertilization (IVF) procedures also contribute to accretas. This is related to the IVF stimulation protocols. Studies have shown that IVF induces morphological and structural changes and can disrupt the expression of relevant genes in the endometrium. These changes could contribute to abnormal implantation.8

The most important concerning combination of risk factors for accreta is placenta previa with a history of prior cesarean section (Table 5-1). In a prospective study, the frequency of accreta increased in proportion with the growing number of cesarean deliveries. Previa at the time of their first cesarean, the risk was 3%, but this risk dramatically increases. Current previa with current cesarean being their third increases the risk of accrete to 40% and a mother having her five or more cesarean has a 67% risk of accreta.9

Serum screening used to assess for aneuploidy risk in pregnancy has been associated with adverse outcomes, such as preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. Both of these are thought to be diseases of abnormal trophoblastic invasion. Studies have shown an association between placenta accreta and elevated msAFP and fbHCG in second trimester maternal serum screening.10,11 If placenta accreta develops in the first trimester and there is a disruption of the maternal-placental barrier, it would correlate with an alteration of PAPP-A levels.

Mothers who have had an elevated msAFP of >2 or 2.5 MoM have also been associated with AIP. An elevated msAFP can support an ultrasound-based diagnosis of accreta. The elevated msAFP alone is an inconsistent finding and is not useful by itself for diagnosis. In addition, a normal msAFP does not exclude the diagnosis of accreta.

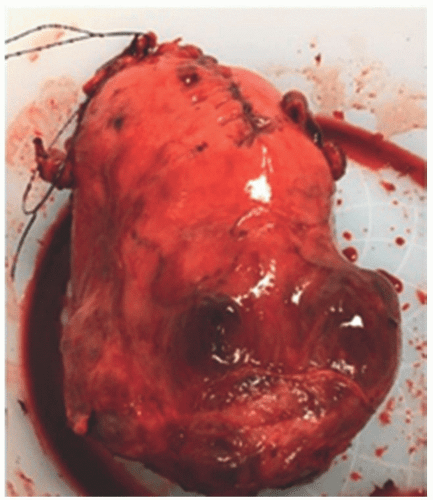

FIGURE 5-2 Uterus after cesarean hysterectomy performed at 34 weeks. Specimen includes uterus with placenta percreta, which had bladder invasion. |

The most important concerning combination of risk factors for accreta is placenta previa with a history of prior cesarean section.

FIGURE 5-3 Uterus after cesarean hysterectomy performed at 29 weeks due to preeclampsia with severe features and vaginal bleeding. Noted to have placenta increta. |

TABLE 5-1 Risk of Accreta Based on Presence or Absence of Placenta Previa and the Number of Cesareans | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

ULTRASOUND: PRIMARY DIAGNOSTIC TOOL

In pregnancy, ultrasound is the primary modality of choice to assess not only the fetus, but the placenta as well. This method is inexpensive and noninvasive. There are multiple uses of ultrasound to further assess in the diagnosis of abnormally adherent placenta. In conjunction with normal 2D ultrasound, color flow Doppler and 3D power Doppler with multislice viewing can add additional layers to help increase the confidence in the diagnosis.

The best imaging method is high-frequency transvaginal ultrasound because it improves the near-field resolution interface between the placenta and lower uterine segment. This is especially helpful in cases of placenta previa or posterior placenta. Ideally, placenta accreta is first suspected because of findings on ultrasound when the patient is asymptomatic.

Authors reported that ultrasound is a useful tool to diagnosis accreta with a 77% to 93% sensitivity and a 71% to 98% specificity.12 Studies have also shown that the prevalence of ultrasound findings suggestive of accrete changes throughout the pregnancy.

Assessment of the Site of Implantation

First-Trimester Ultrasound

First-trimester ultrasound is important, especially in mothers with a history of a previous cesarean. An early first-ultrasound at 6 to 9 weeks gestational age allows for early assessment of implantation to evaluate for normal (Figure 5-5A) versus low implantation/cesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) (Figure 5-5B). Timor-Tritsch developed a measurement system to assist in diagnosis of CSPs (Table 5-2).13 He used transvaginal ultrasound to obtain a sagittal view of the uterus. Then he measured the uterine size by drawing a straight longitudinal line from the external cervical os to the fundus of the uterus. The midpoint of the line was determined and this original line was transected by a perpendicular line, marking the middle of the uterine size. He then measured the distance from the external cervical os to the center of the gestational sac and the most distal point of the gestational sac and he found significant differences in these measurements.

First-trimester ultrasound is important, especially in mothers with a history of a previous cesarean. An early first-ultrasound at 6 to 9 weeks gestational age allows for early assessment of implantation to evaluate for normal versus low implantation/cesarean scar pregnancy

A panoramic, longitudinal, sagittal scan can be used to determine the location of the gestational sac. Divide the uterus in half with an imaginary line. If the gestational sac is above the line, it is most likely a normal implantation. If the gestational sac is below it, suspect a CSP or a cervical pregnancy and hence high risk of accreta.

It is hypothesized that cesarean scar pregnancy and accreta are not separate entities but a continuum of the same condition. A cesarean scar pregnancy is a precursor to accreta.13

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree