Diagnosis of Congenital Toxoplasmosis

INTRODUCTION

Abundant and convincing evidence demonstrates that medicines block transmission of Toxoplasma gondii from the pregnant woman to her fetus, kill tachyzoites, reduce or eliminate parasite burden, reduce or eliminate eye disease, reduce or eliminate brain disease, reduce severity of disease, eliminate meningitis, treat meningoencephalitis, and lower immune markers of infection.1–4 Earlier, there was some controversy in the literature (discussed in Reference 4), but currently, review of data from in vitro and experimental animal studies, attention to older publications of studies that were performed meticulously (reviewed in References 1–4), and several recent studies have clarified the efficacy and benefits of proper, early, and rapid diagnosis and medical treatment.5,6 The recent data demonstrate how important it is to establish such diagnosis and treatment as the standard for medical care to prevent the loss of productive lives to this disease. The time when the acute infection is diagnosed and treated is critical.1–5 The earlier the infection is treated, the better the outcomes will be for fetus, infant, and congenitally infected person.5,6 For this reason, the focus of this chapter is to make clear how diagnosis and treatment of the fetus and infant can be optimized and how this is carried out practically.

PREVENTION WITH EDUCATION DURING GESTATION

The approach to diagnose, prevent, and treat infections of the fetus is summarized in Tables 116-1 to 116-8 and Figures 116-1 to 116-4. The pregnant woman with acute acquired T. gondii infection and the mother of a congenitally infected infant may have retinal disease caused by the parasite and should have a retinal examination. Simple instructions concerning avoiding means of acquisition of the parasite provide an opportunity to prevent some fetal infections in the pregnant woman. An educational pamphlet is provided in Chapter 57, Figure 57-3. This may be downloaded from the Internet without charge or copyright (http://www.toxoplasmosis.org/pamphlet.pdf) so it can be provided to pregnant patients or those considering becoming pregnant. However, environmental contamination by oocysts is common and often unrecognized. Risk cannot be eliminated entirely by education. Infection may occur in persons with no recognized risk factors.

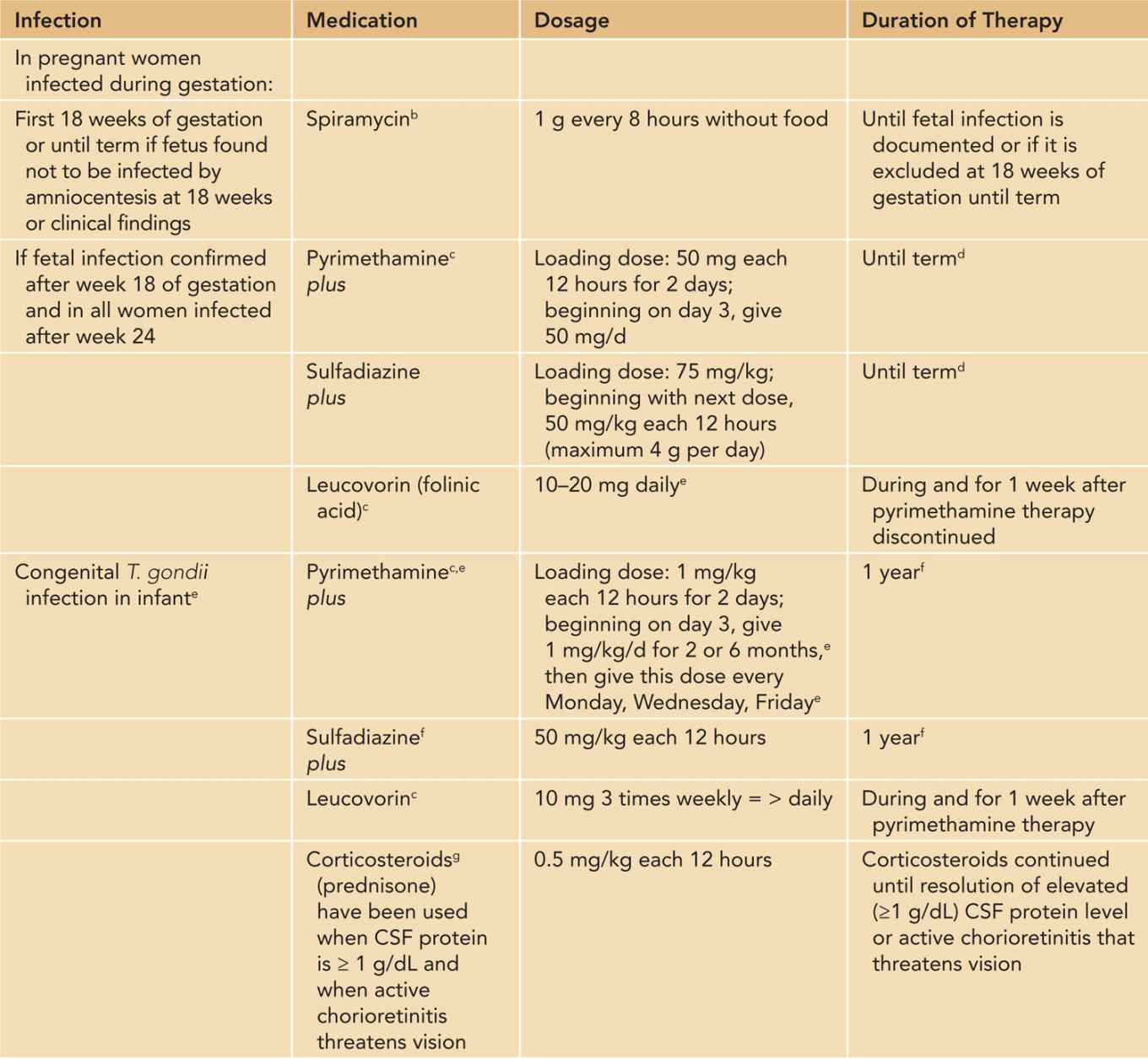

Table 116-1 Guidelines for Treatment of Toxoplasma gondii Infection in the Pregnant Woman and Congenital Toxoplasma Infection in the Fetus, Infant, and Older Childrena

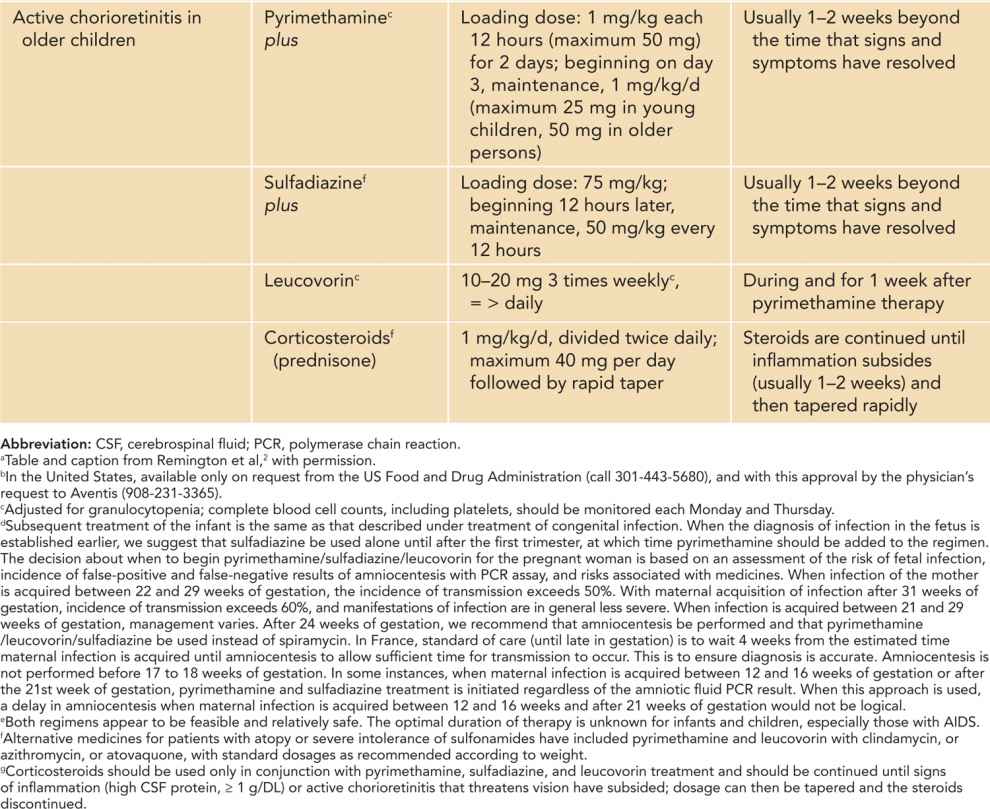

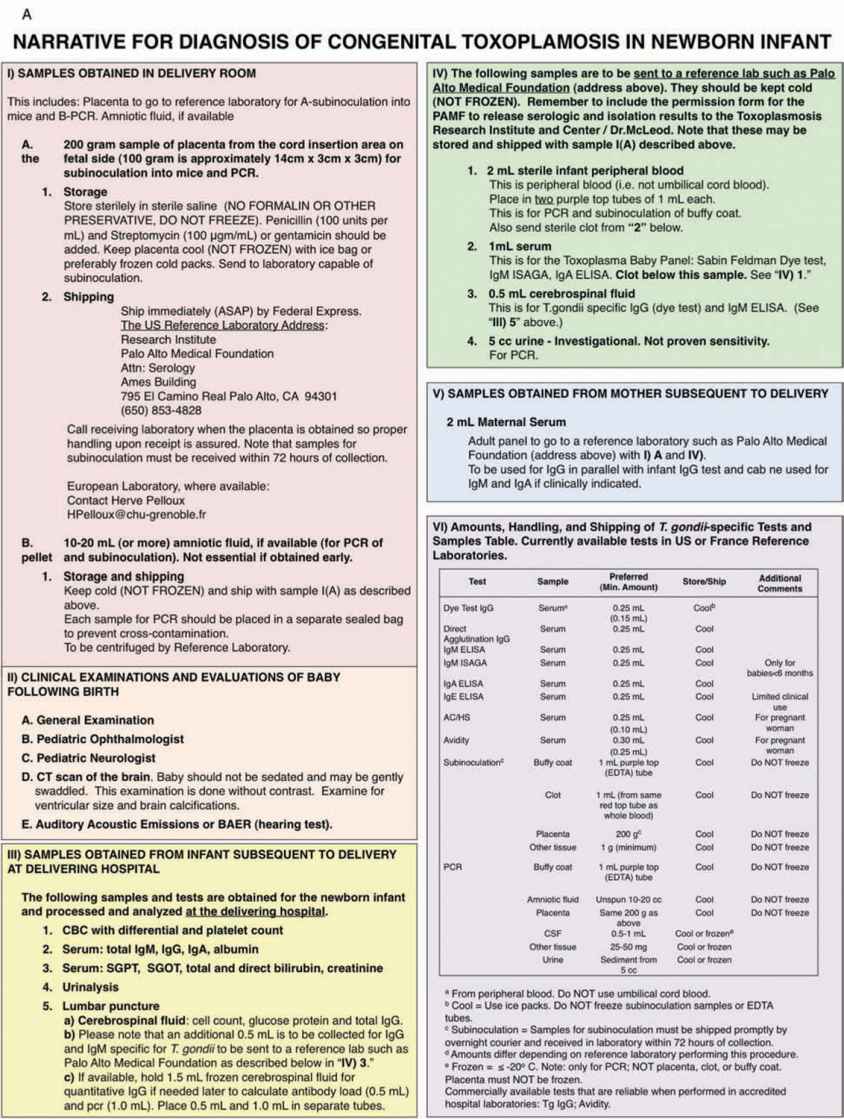

Table 116-2 Samples Obtained in Delivery Room

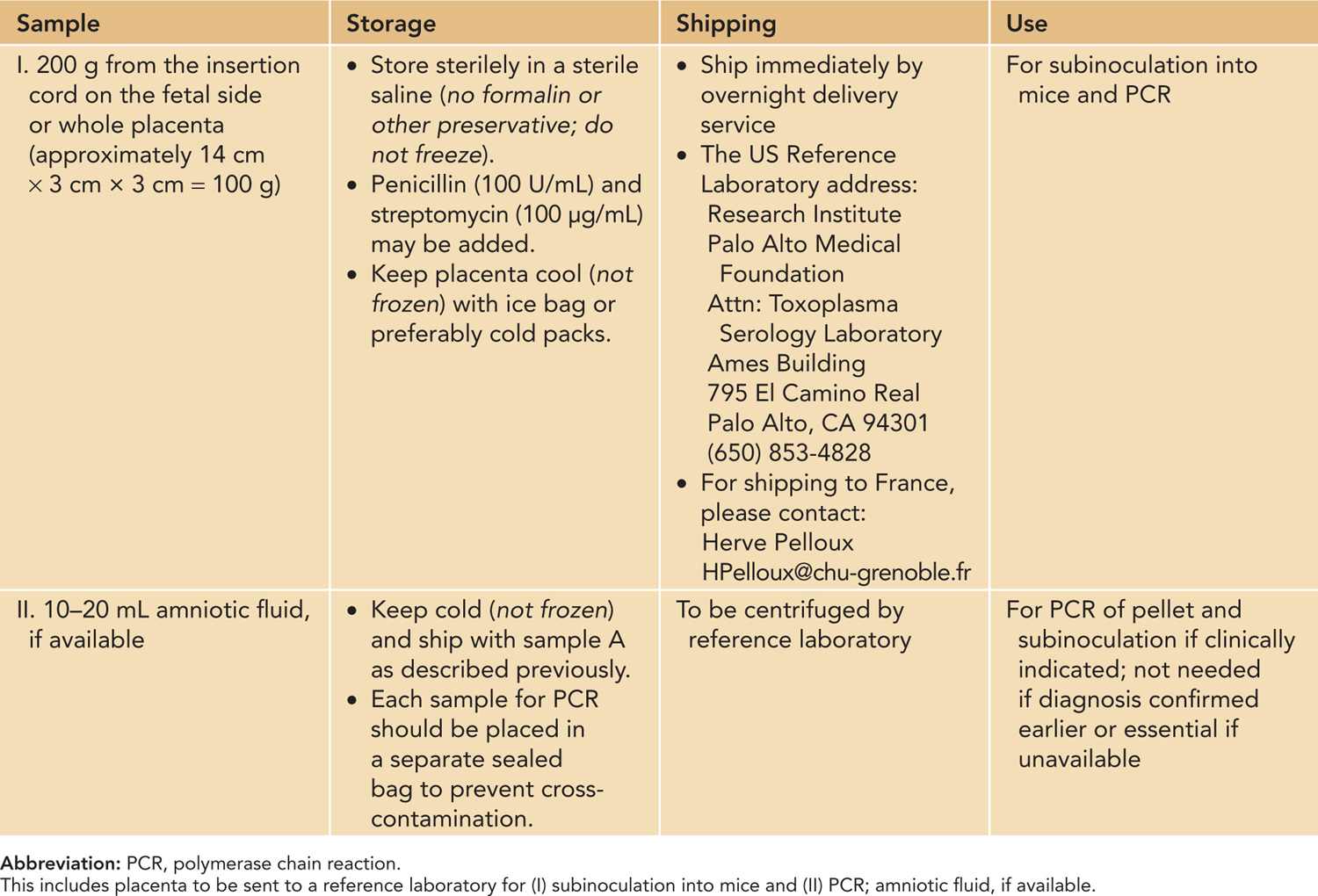

Table 116-3 Samples Obtained From Infant Subsequent to Delivery

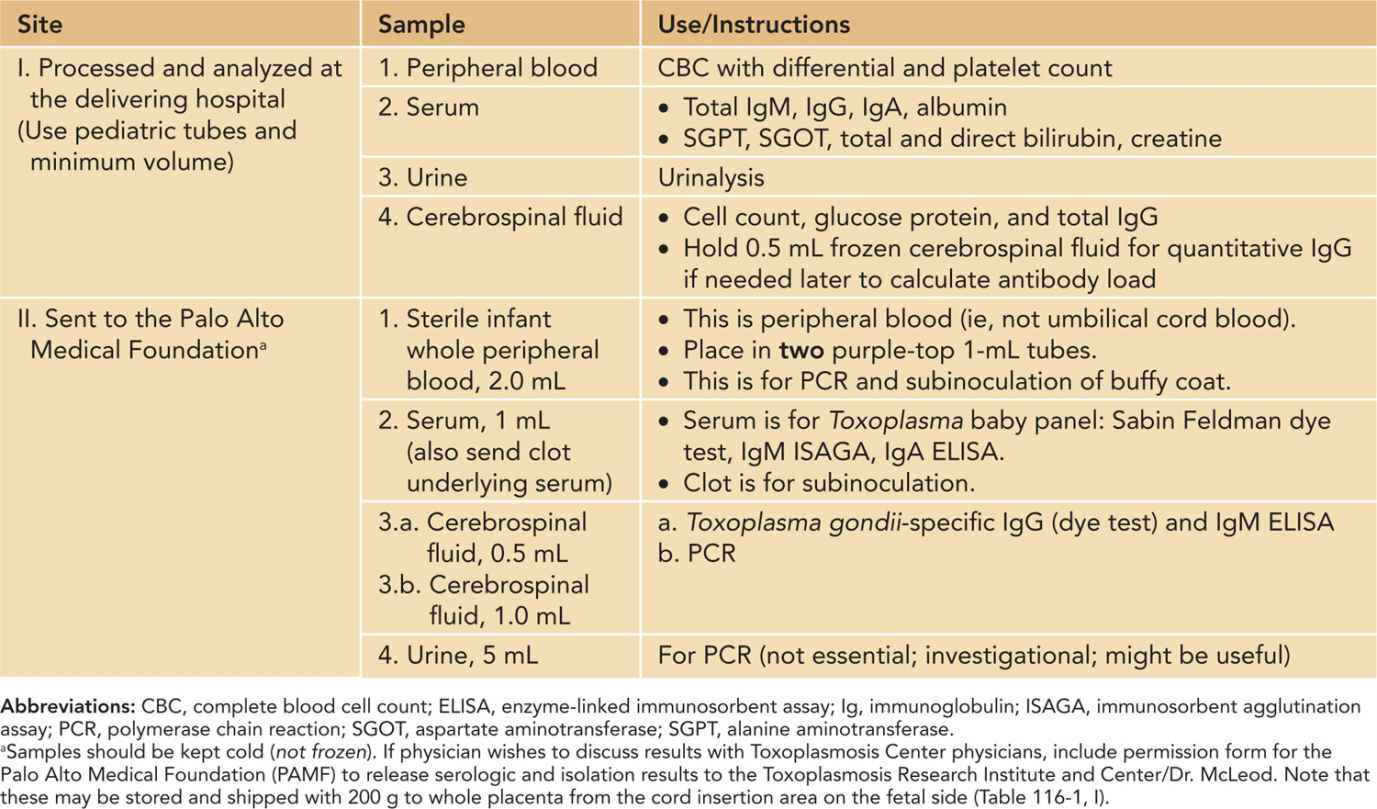

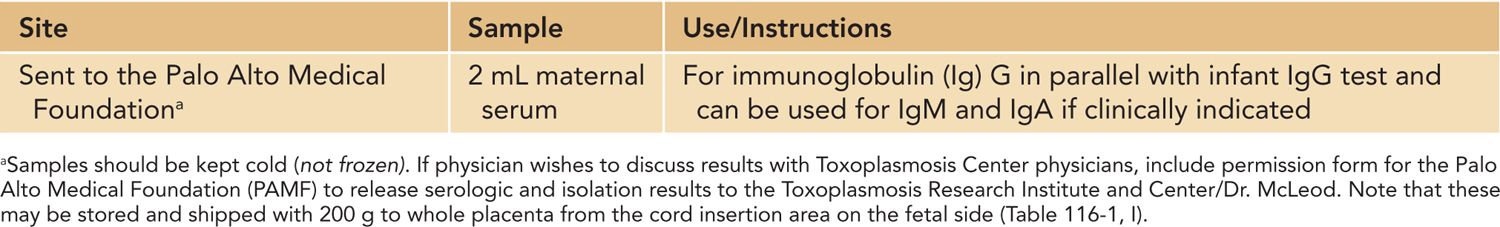

Table 116-4 Samples Obtained From Mother Subsequent to Delivery

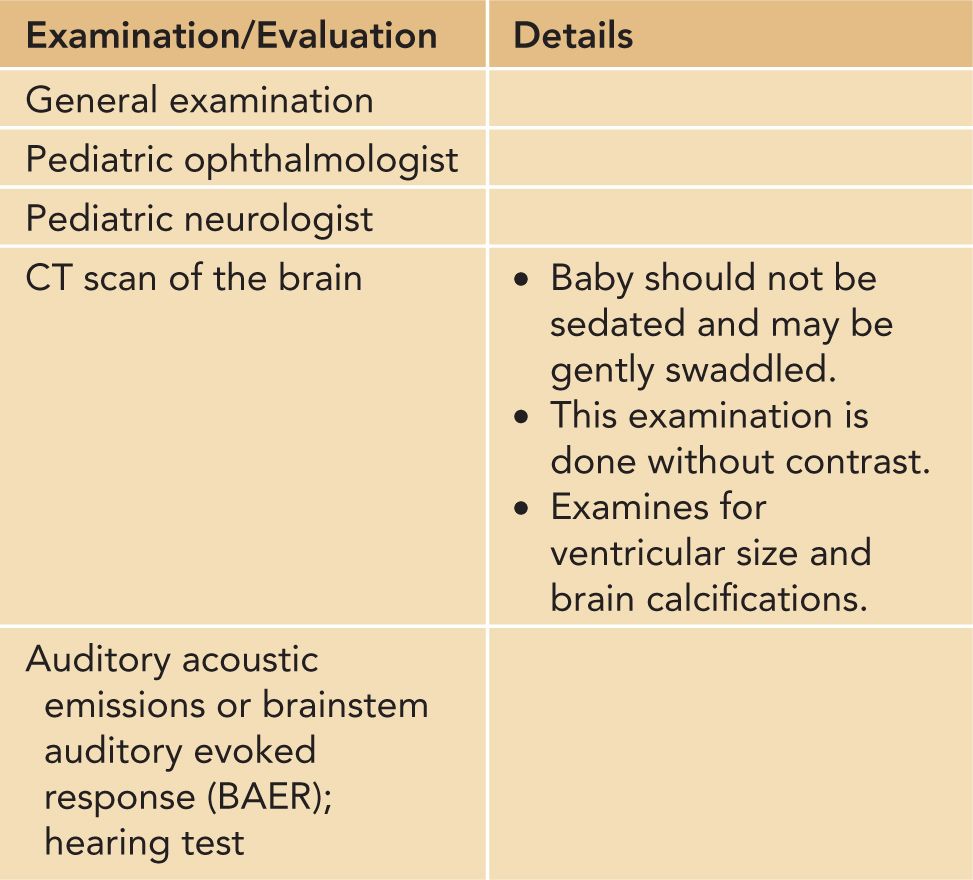

Table 116-5 Examinations and Evaluations of Baby Following Birth

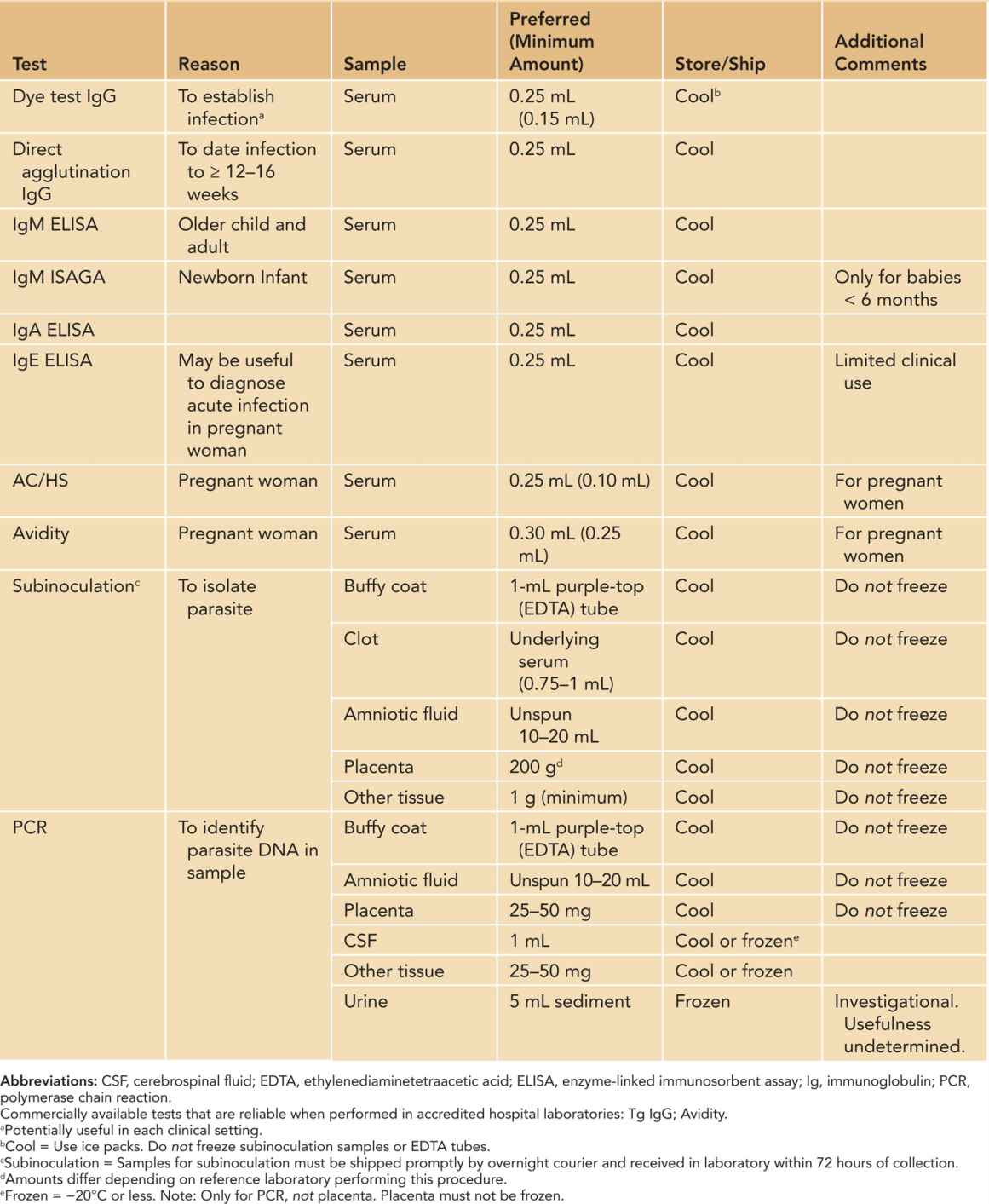

Table 116-6 Amounts, Handling, and Shipping of Samples (Currently Available Tests in United States or France Reference Laboratories)

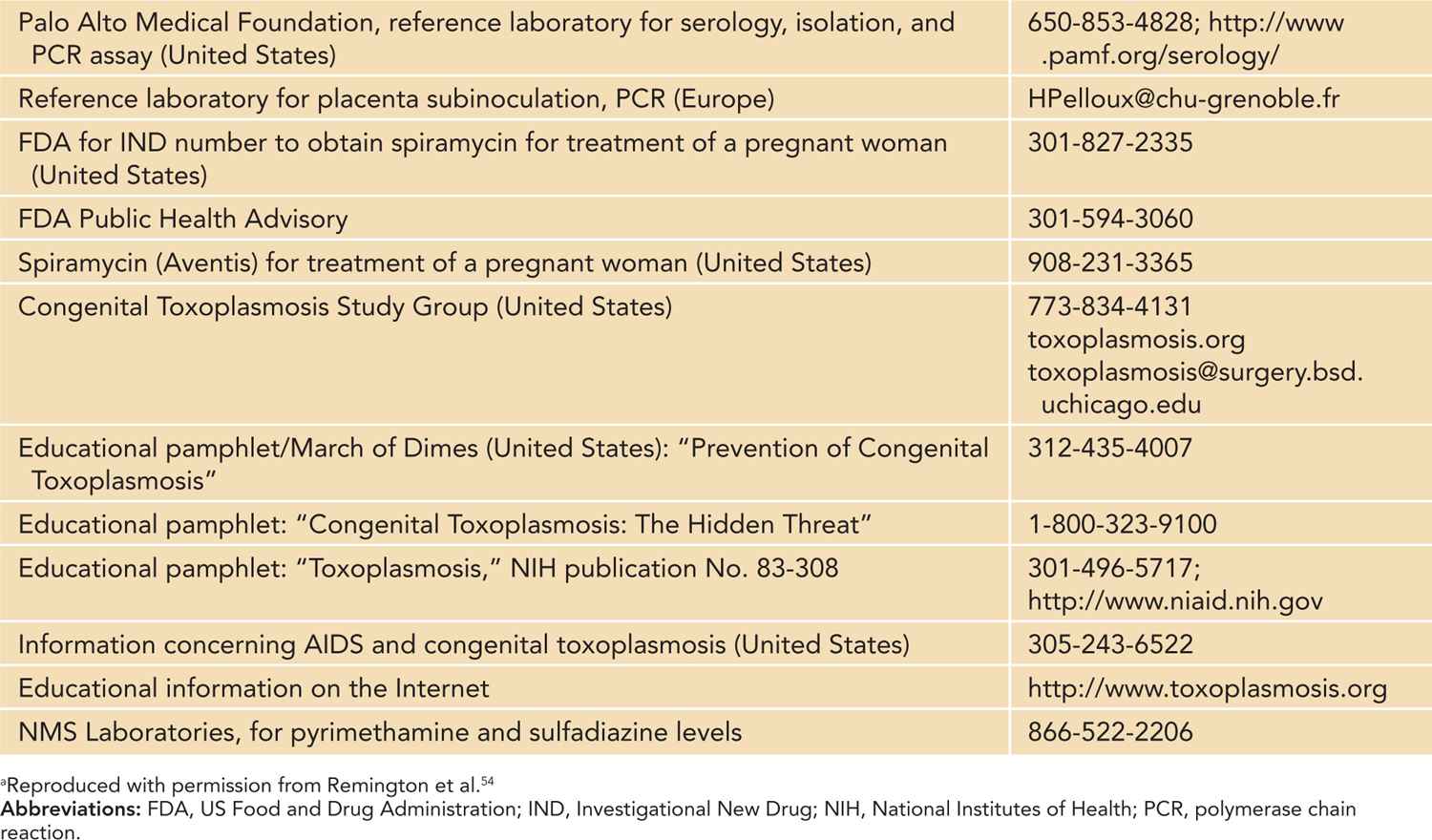

Table 116-7 Contact Information for Reference Laboratories and Programsa

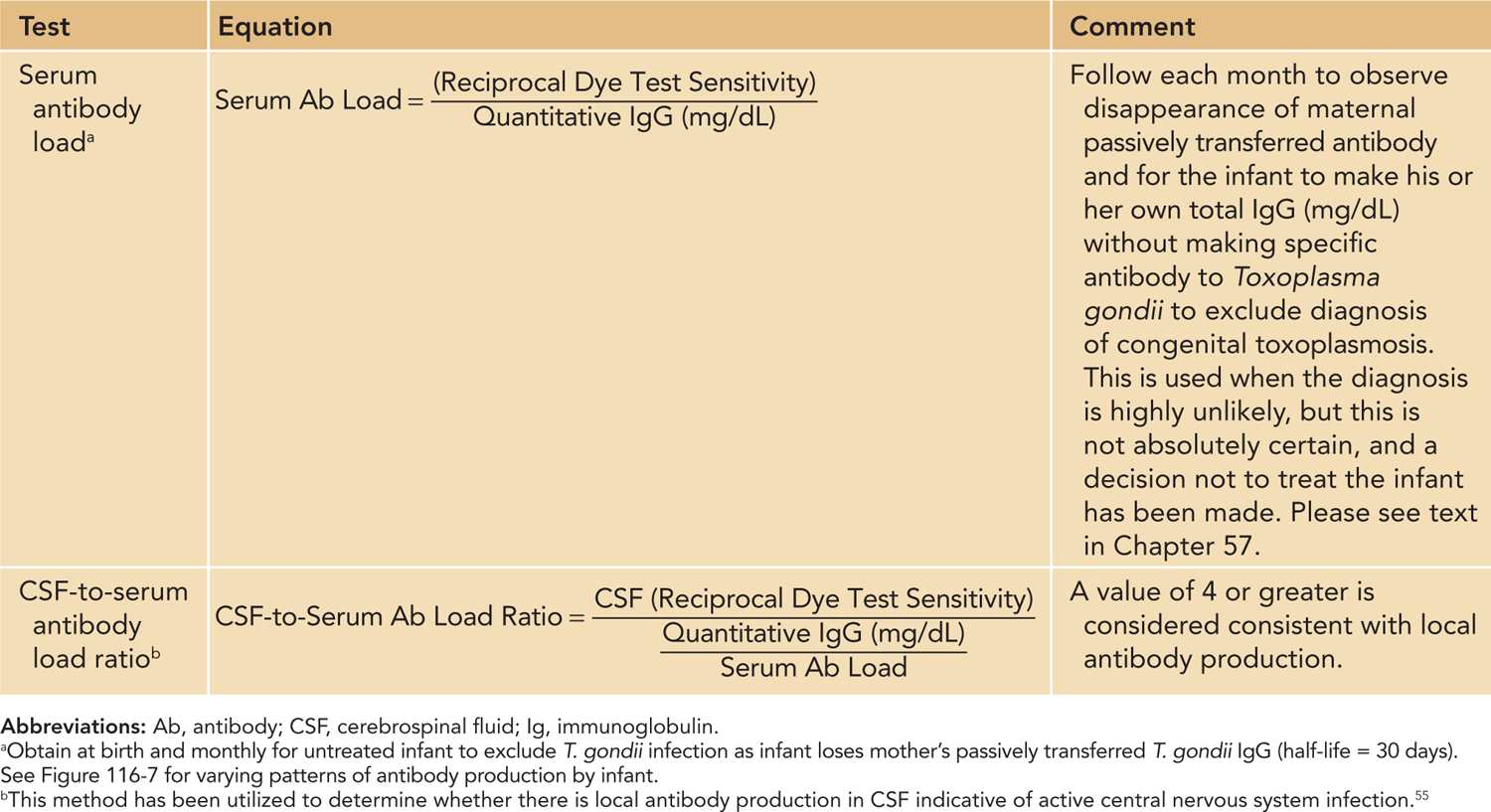

Table 116-8 Calculations of Antibody Load

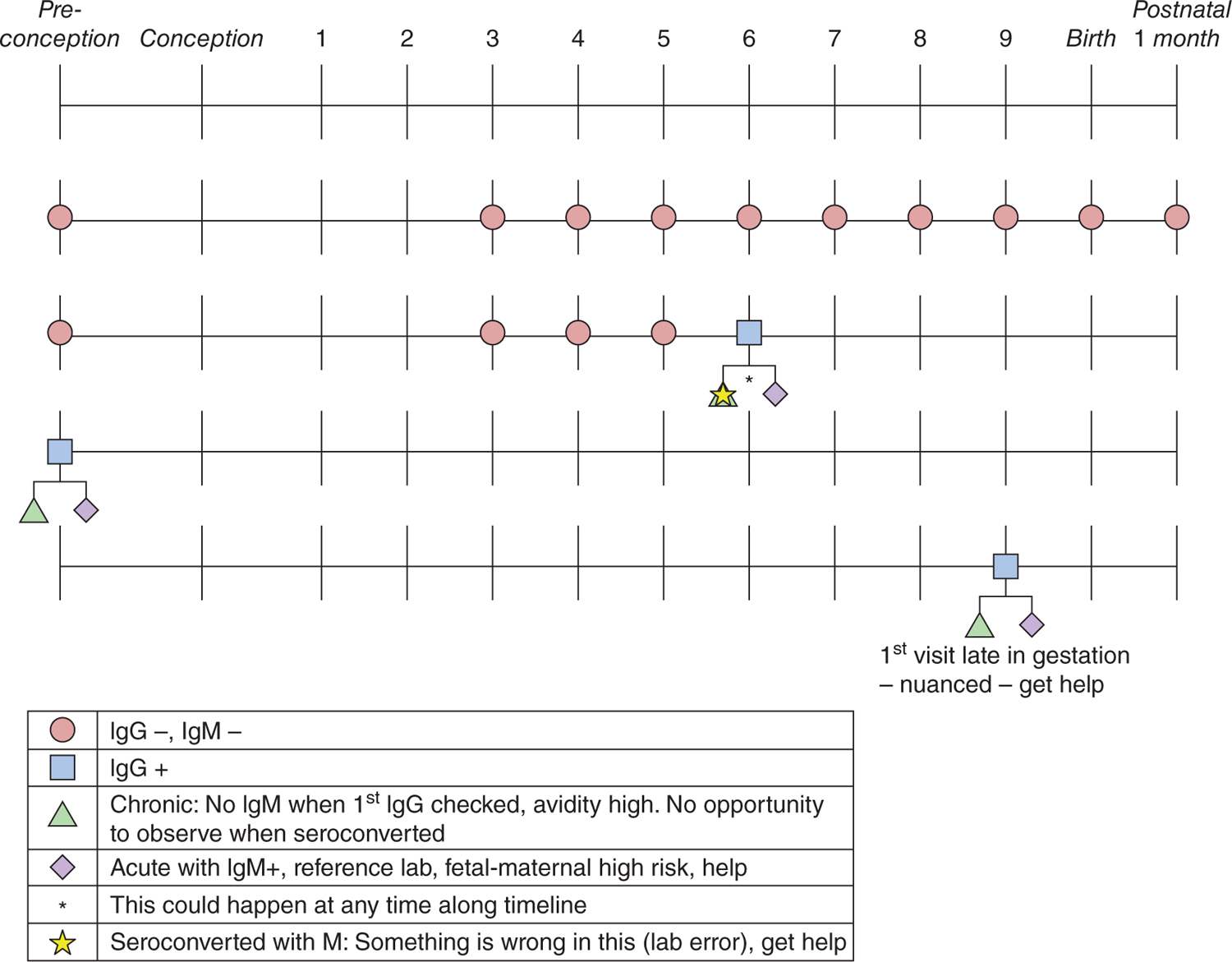

FIGURE 116-1 Algorithm for screening for acquisition of primary Toxoplasma infection during gestation. Ig, immunoglobulin.

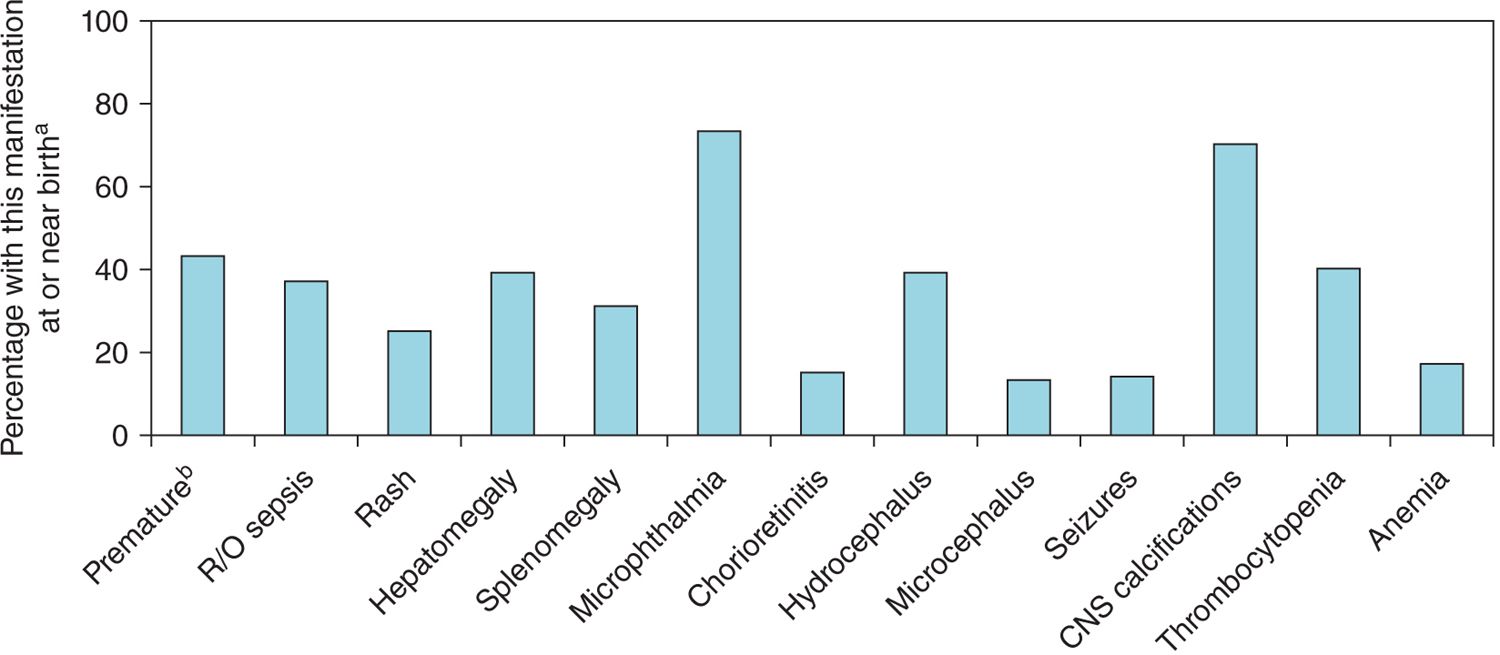

FIGURE 116-2 Manifestations at presentation, National Collaborative Chicago-based Congenital Toxoplasmosis Study (NCCCTS; 1981–2009). aInfants diagnosed with congenital toxoplasmosis in the newborn period and referred to the NCCCTS in the first year of life. bLess than 37 weeks’ gestation. CNS, central nervous system; R/O, rule out.

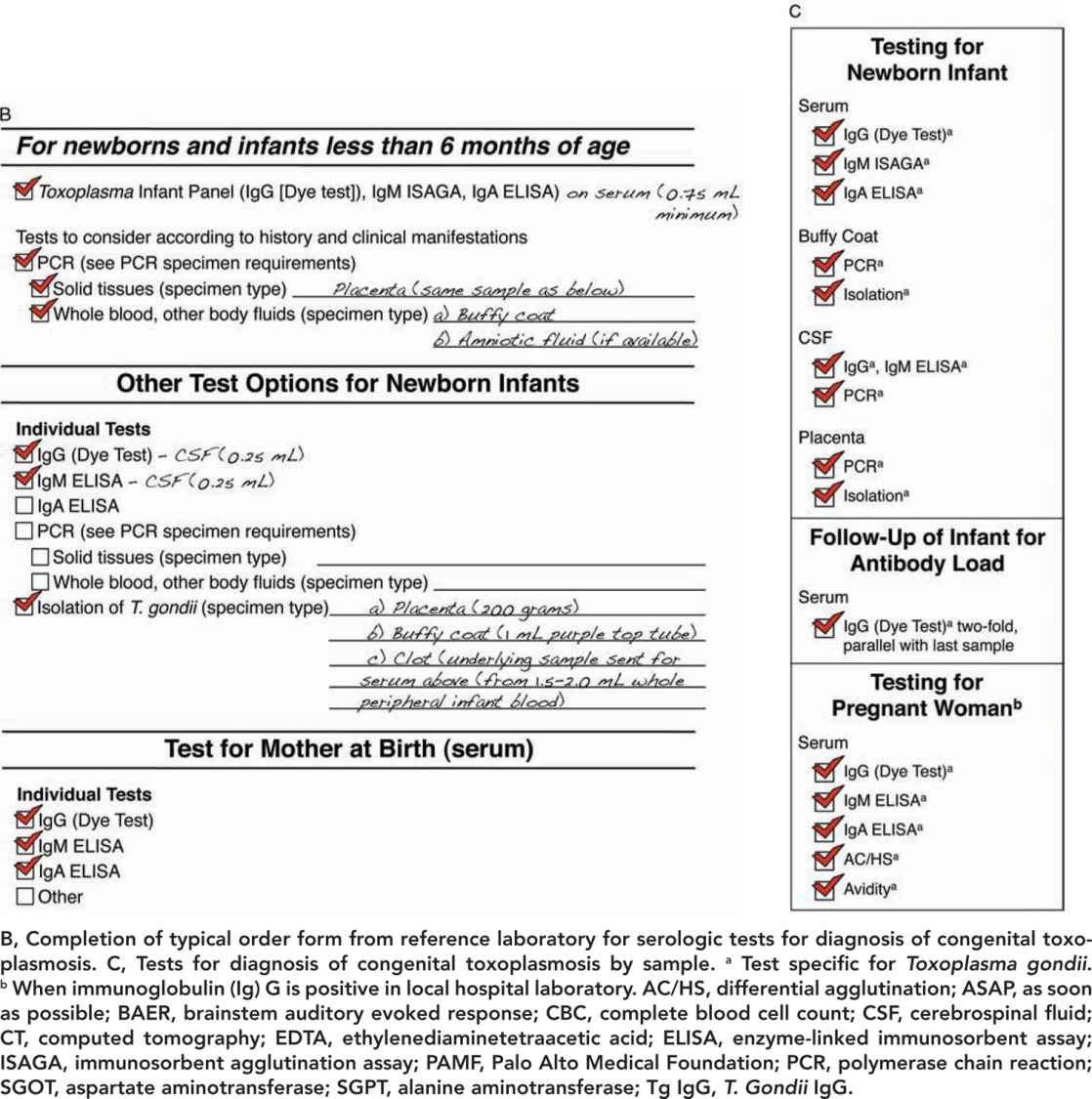

FIGURE 116-3 A, Approach for tests to diagnose congenital toxoplasmosis in the newborn infant.

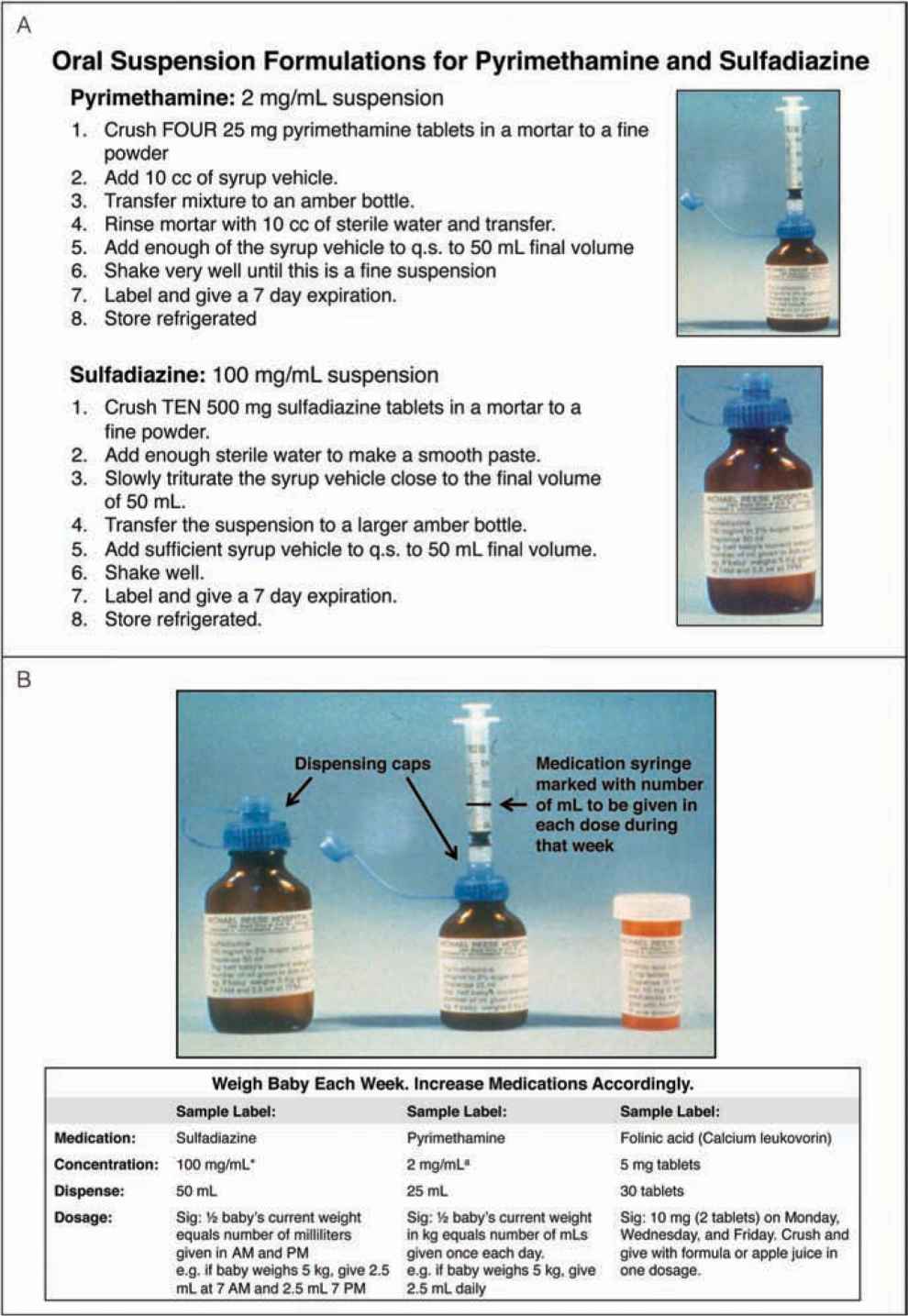

FIGURE 116-4 A, Method of compounding oral suspension formulations for pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine. B, Method of administering medications used to treat congenital toxoplasmosis. aSuspended in 2% sugar solution. Suspension at usual concentration must be made up each week. Store refrigerated. First loading dose for 2 days is 1 mg/kg twice daily. Third-day dose is 1 mg/kg/d. With in utero treatment, no loading dose postnatally is used. q.s., quantity sufficient. (A, reproduced with permission from Remington et al2; B, reproduced with permission from McAuley et al24.)

GESTATIONAL SCREENING: DIAGNOSIS, PREVENTION, AND TREATMENT OF THE ACUTELY INFECTED PREGNANT WOMAN AND FETUS

Figure 116-1 and Figure 57-23 in Chapter 57 summarizes an approach used universally in France, where it successfully detects seroconversion during gestation to prevent transmission to the fetus and to identify infection in the fetus. This allows treatment without delay. In this approach,1–21 currently utilized in some of the best obstetrical practices in the United States, serologic screening for T. gondii specific antibody to immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin M (IgM) is performed once a month during gestation for all pregnant women who are seronegative and is initiated by the 11th week of gestation. Ideally, such screening would, and sometimes does, begin immediately before or early in gestation at the time pregnancy is noted, even when this is earlier than 11 weeks’ gestation. Screening is continued monthly through the time the infant is born and is performed at birth and when the infant is 1 month old to detect infections acquired late in gestation. This approach presents the opportunity to confirm when a pregnant woman seroconverts (ie, newly develops specific IgG antibody to T. gondii). This is done so that acute acquired infection can be proven by more specialized testing. In the United States, this specialized testing is performed in a reference laboratory (Table 116-7). This then enables the physician to prevent transmission from the newly infected pregnant woman to her fetus through treatment of the mother with spiramycin early in gestation (Table 116-1). Fetal ultrasounds are obtained every 2 weeks until term for mothers who seroconvert. It is then possible to diagnose infection in the fetus by ultrasound or amniocentesis. It enables treatment of the infected fetus when diagnosed by amniocentesis with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of the amniotic fluid for T. gondii DNA or via ultrasound. The infected fetus can then be treated by treatment of the mother with pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine (with leucovorin, folinic acid). Clindamycin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin are second-line medicines used for pregnant women with significant hypersensitivity to sulfadiazine, but there are no data concerning their efficacy. Treatment of the infant continues after birth as described in Chapter 57 and here (Table 116-1; Figure 116-4).

BIRTH: PLACENTA SAMPLES OBTAINED IN THE DELIVERY ROOM

Table 116-2 outlines how the placenta should be processed in the delivery room and afterward.2

CLINICAL EVALUATION OF THE INFANT

Clinical evaluation of the infant is summarized in Table 116-5. Figures 116-2 and 57-8 and Tables 57-4 to 57-8 include common manifestations of this infection,1–45 which should lead to prompt diagnostic evaluation. This highlights the importance of recognition by neonatologists and others caring for such an infant that these findings are manifestations of congenital toxoplasmosis. Details of diagnostic evaluation of the infant to exclude or establish manifestations of this disease are in Tables 116-2 to 116-6 along with some comments about evaluation of the mother and other family members.2,40,42–47 The tables and figures in Chapter 57 also differently illustrate manifestations of this infection and diagnostic approaches.

SAMPLE AMOUNTS NEEDED FOR SPECIALIZED TESTING AND USEFUL CONTACT INFORMATION

One of the areas of confusion sometimes is which samples and how much of them should be obtained for particular tests. Therefore, Tables 116-2 to 116-4 and 116-6 provide this information. Table 116-7 provides contact information helpful for diagnosis and treatment and counseling pregnant women and their families and families for whom this diagnosis is suspected or proven.

ANTIBODY LOAD IN SERUM AND CEREBROSPINAL FLUID

In certain circumstances (eg, birth of an infant who is completely normal with a low likelihood of transmission from an acutely infected mother, had negative amniotic fluid PCR for T. gondii infection in a reference laboratory, and had no manifestations at birth consistent with infection), a decision is made with the parents not to treat the infant but rather to follow serum antibody load. This is measured as shown in Tables 116-8 and 57-25 (Chapter 57). In this case, a physician monitors the measurement of IgG antibody specific for T. gondii each month. Serum is diluted 2-fold in parallel with the previous month’s sample and sensitivity of the dye test noted. Passively transferred maternal T. gondii-specific IgG will fall by 50% because the half-life of IgG is 30 days. At the same time, the physician monitors that and when the infant begins making his or her own IgG (quantitative immunoglobulin milligrams per deciliter measured in the local hospital’s laboratory; also see discussion in Chapter 57).

A similar equation can be used to calculate antibody load in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to demonstrate local production of antibody to T. gondii

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree