CHAPTER 5 Diagnosis

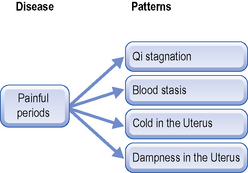

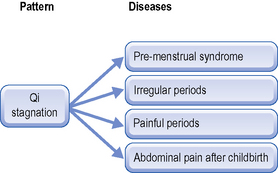

Thus, for each Chinese ‘disease’ there are several patterns. For example, the disease of ‘Painful Periods’ may manifest with several patterns such as Liver-Qi stagnation, Liver-Blood stasis, Cold in the Uterus, Damp-Heat in the Uterus (Fig. 5.1). On the other hand, each pattern may be found in many different diseases and the important point is that, although the pattern is the same, its treatment will differ somewhat according to the disease with which it is manifesting. For example, the pattern of Liver-Blood stasis may be found in many different gynecological diseases such as ‘Heavy Periods’, ‘Flooding and Trickling’, ‘Painful Periods’, ‘Bleeding between Periods’, ‘Abdominal Masses’, etc. and its treatment will differ in each case (Fig. 5.2).

The discussion of diagnosis in gynecology will be carried out according to the following topics:

Interrogation

The main areas of questioning are:

Menstruation

Menarche

Cycle

It should be borne in mind that for approximately the first 2 years from menarche, the menstrual cycle may be somewhat irregular: this is quite normal. To have an idea as to how the periods were in the beginning, I therefore always ask how they were about 2 years after menarche. The Golden Mirror of Medicine says: “When periods come early, it is due to Heat, when late, it is due to Blood stasis.”1

Colour

The Golden Mirror of Medicine says:

When the colour [of menstrual blood] is pale and amount scanty, it is due to Deficiency, the period is not usually painful; if the colour is dark and the amount heavy and there is pain, it is due to Fullness.2

Pain

Pre-menstrual symptoms

Pre-menstrual irritability with insomnia and thirst may be due to Liver-Fire and/or Heart-Fire.

Pain

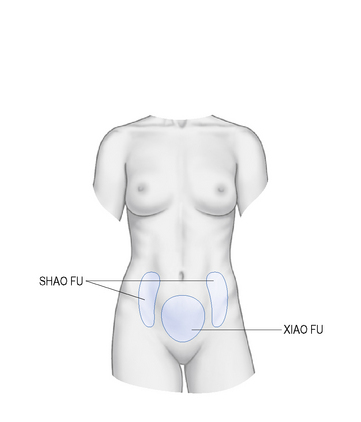

As for the significance of the area of pain, the central area of the lower abdomen below the umbilicus is called xiao fu, i.e. ‘small abdomen’, whereas the lateral sides of the abdomen are called shao fu, i.e. ‘lesser abdomen’ (Fig. 5.3). Pain in the central area of the lower abdomen (the ‘small abdomen’) is usually related to the Kidneys and the Directing Vessel. Pain in the lateral sides of the abdomen (the ‘lesser abdomen’) is usually related to the Liver channel and the Penetrating Vessel.

The following are therefore the main areas of interrogation with regard to abdominal pain: