Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes affects 1 in 400–500 children and adolescents. It is defined as persistent hyperglycaemia (fasting blood glucose >7 mmol/L). The diagnosis has a major impact on the child and the family in terms of their daily life; the risk of serious illness such as diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and the risk of long-term complications such as retinopathy, renal failure, cardiovascular disease and neuropathy.

Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes in children is usually insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (type 1) due to autoimmune destruction of the beta cells in the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas, resulting in a lack of insulin. The lack of insulin means that glucose cannot be utilized, resulting in hyperglycaemia. The high glucose concentration in the blood spills over into the urine, causing an osmotic diuresis with polyuria and dehydration. This leads to excessive thirst, and weight loss. Because the cells cannot utilize glucose they switch to metabolizing fats, leading to the production of ketones, resulting in acidosis.

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

In this form of diabetes the pancreas is able to secrete insulin but there is peripheral insulin resistance. Until recently type 2 diabetes was rare in childhood, but the incidence is increasing, probably related to increased calorie intake and reduced exercise. Management is dietary control of carbohydrate and oral hypoglycaemic agents (e.g. sulphonylureas). In some cases the need to produce high levels of insulin leads the pancreas to ‘burn out’, such that insulin therapy becomes necessary.

Other Types of Diabetes Mellitus

It is increasingly recognized that there are genetic forms of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus which present in childhood. They are often due to impaired secretion of insulin from the pancreatic beta cells. In other cases the diabetes is caused by drugs (e.g. corticosteroids following transplantation) or by disease processes (e.g. cystic fibrosis or pancreatitis) or is associated with genetic syndromes.

Initial Presentation of Type 1 Diabetes

Children usually present with a short (2–3 week) history of lethargy, weight loss, polyuria and thirst. The polyuria may cause a recurrence of bedwetting. If the symptoms are not recognized the child may develop signs of diabetic ketoacidosis with abdominal pain, vomiting and eventually coma. Newly diagnosed children who are ketoacidotic will need admission to hospital to correct dehydration and commence intravenous insulin.

Intensive education of the child and family is needed undertaken by diabetic nurse specialist, paediatric diabetologist and specialist dietician. The child and family are taught how to inject the insulin, monitor blood glucose, test for ketones, and recognize the signs of hypoglycaemia. Children are encouraged to wear a Medic-Alert bracelet, giving details of their condition in case of sudden hypoglycaemic collapse. Education should be structured so that every child has access to the full support available and their progress in building expert knowledge can be verified.

Growing Up with Diabetes

The education given to families at the time of diagnosis is crucial in developing the right approach to their child’s diabetes. As the child gets older they can gradually take on more of the responsibility themselves, including injecting insulin and monitoring blood glucose levels. Normal healthy diet should be encouraged to ease blood sugar regulation.

Managing any chronic condition places an added difficulty on emotional well-being particularly through times when it is normal to show rebellious defiant behaviour such as at adolescence. Diabetes increases the risk of psychological problems (such as eating disorder) linked to poor compliance. The diabetes team need specialist skills in engaging and motivational interviewing of adolescents to help manage these problems.

Insulin Therapy (Type 1 Diabetes)

Many children go through a ‘honeymoon’ period soon after diagnosis where they need very little insulin, as they still produce some endogenous insulin. More insulin is often required as they go through the pubertal growth spurt. Insulin is usually delivered by an injection pen. Various insulin regimens are used.

- Twice daily regimen: the insulin is given as a mixture of rapid-acting insulin (peak at 2–4 hours) and intermediate-acting isophane insulin (peak at 4–12 hours). This is administered subcutaneously in the arms, thighs, buttocks or abdomen, before breakfast and before the evening meal.

- Basal bolus regimen: this provides a long-acting insulin at night and rapid-acting insulin given before each meal, based on the calculated carbohydrate intake.

An alternative to these regimens is continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) of rapid acting insulin via a pump, with the ability to increase the rate (bolus) during mealtimes. The insulin is infused through a cannula, which is changed every third day. This system can give better glycaemic control and fewer hypoglycaemic episodes.

Monitoring

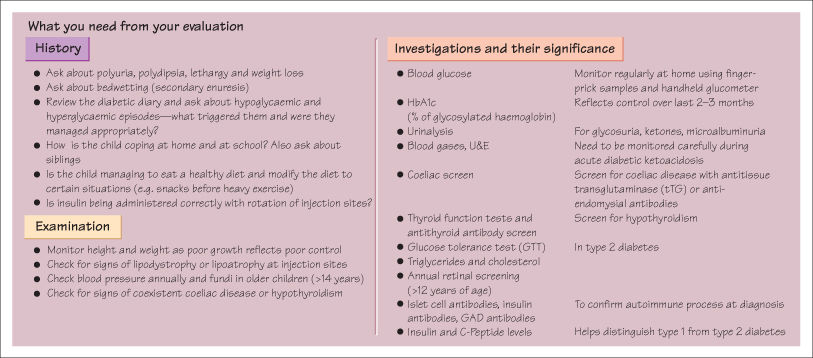

Control is assessed by keeping a blood sugar diary and measuring HbA1c levels, which measures glycaemic control in the preceding few months. The family need to be warned of the symptoms of hypoglycaemia (see opposite) and have carbohydrate available (dextrose tablets) at all times. Screening for complications and associated conditions (thyroid disease, coeliac disease) is performed regularly.

KEY POINTS

- Diabetes is very common: it occurs in 1 in 500 children.

- Presentation is with a short history of weight loss, polyuria and polydipsia.

- DKA can be life-threatening and needs high-dependency treatment

- Insulin is given subcutaneously in a number of different regimen to best suit the child.

- Patients must be able to recognize and treat hypoglycaemia.

- Type 2 diabetes is becoming more common in children.