Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

David A. Podeszwa

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is a spectrum of disorders of the developing hip. DDH evolves over time and presents in different forms at different ages. DDH may not be detectable at birth, and hence, the preferred term developmental and not congenital. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) defines DDH as a condition in which the femoral head has an abnormal relationship to the acetabulum.1 Dislocation is defined as complete displacement of a joint, with no contact between the original articular surfaces. Subluxation is defined as displacement of a joint with some contact remaining between the articular surfaces. Dysplasia refers to abnormal or deficient development of the acetabulum. A teratologic dislocation is a distinct condition that occurs before birth, is generally nonreducible on physical exam, and causes the hip to be stiff. Teratologic dislocations are frequently associated with neuromuscular conditions, particularly arthrogryposis and myelodysplasia, and treatment depends on the underlying condition.

The incidence of DDH varies based on the condition studied, method of study (clinical exam vs. radiologic exam), race, and geography. Classically, the overall incidence of some form of hip instability has been reported at 1 per 1000.2 The reported rate of hip dislocation ranges from 1 to 1.5 cases per 1000 live births. Clinical instability has been documented in approximately 2.3 cases per 100 live births, and an ultrasound abnormality has been documented in approximately 8 cases per 100 live births. Bilateral DDH occurs in 20% of all patients with this disorder.

As breech positioning can be considered a “packaging” issue (intrauterine crowding) predisposing to DDH, torticollis, metatarsus adductus, and oligohydramnios are other packaging-related conditions strongly associated with DDH. A child with torticollis has a 14% to 20% risk of also having DDH.3 Although clubfoot has not been strongly associated with DDH, up to 10% of children with metatarsus adductus will also have DDH.4 DDH is more common in females and first-born children, and most frequently affects the left hip. Family history also strongly influences the risk of DDH. The risk of a subsequent child having DDH is 6% if there are healthy parents and an affected child, 12% with an affected parent, and 35% with an affected parent and an affected child.

ETIOLOGY

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of DDH is multifactorial, but a number of predisposing factors have been identified, including ligamentous laxity, breech positioning, and postnatal positioning. The maternal relaxin hormone, which allows the maternal pelvis to expand, crosses the placenta and can induce laxity in the child, an effect known to be stronger in females than in males. The footling breech presentation (both hips flexed) is associated with a 2% risk of DDH, and the frank breech position (one or both knees extended) is associated with a 20% risk of DDH.5 Newborn babies wrapped in a hip-extended position, common in the Native American culture, also have a higher incidence of DDH.

CLINICAL FEATURES

CLINICAL FEATURES

The clinical evaluation and diagnosis of DDH can be difficult and can change over time. Thus, close follow-up and documentation of the physical exam are critical. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends a hip exam at 2 weeks, 2 months, 4 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 1 year. The physical exam findings will vary depending on the age of the child and the severity of the condition. The stability of the hip in the neonate is clinically diagnosed by performing the Barlow and Ortolani maneuvers. In the neonatal period, these maneuvers are generally the only physical exam finding suggestive of DDH. These maneuvers are best performed with the child placed supine on a warm, firm surface. The child and examiner must be as relaxed as possible. Dimming the room lights or feeding the child a bottle will often help. If the child is fussy or the examiner is impatient, the exam will be inaccurate.

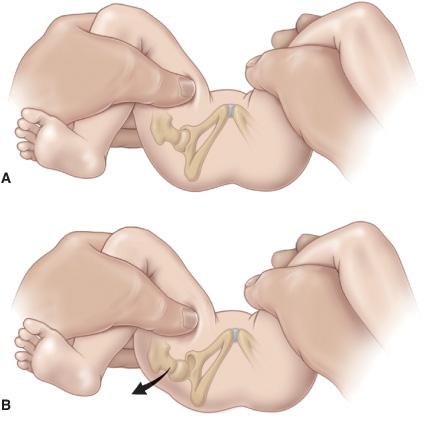

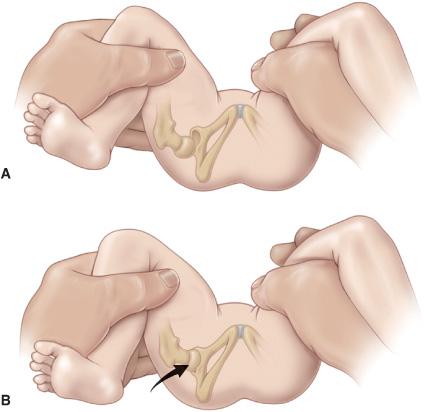

The examiner holds the child’s knees, one in each hand, with the fingers of the examiner over the greater trochanter and the thumb placed along the inner thigh. The hips are examined one at a time. The Barlow test (Fig. 215-1) is an attempt to dislocate the femoral head from within the acetabulum. With the hip flexed 90° with neutral rotation, the hip is adducted and pressure is applied in a posterior direction as an attempt to slide the hip posteriorly out of the acetabulum. With a positive test, the hip will slide posteriorly out of the acetabulum and will be felt to slip back as the posterior pressure is relaxed. The Ortolani test (Fig. 215-2) is an attempt to reduce a dislocated femoral head back into the acetabulum (the opposite of the Barlow maneuver). With the hip flexed 90° and in neutral rotation, the hip is abducted while simultaneously the ring and small fingers are used to gently lift the greater trochanter. When the test is positive, a “clunk” will be felt as the femoral head slides back into the acetabulum. Both of these maneuvers should be repeated multiple times as a smooth arc of motion before proceeding to the opposite hip.

FIGURE 215-1. The Barlow test for developmental dislocation of the hip in a neonate. A: With the infant supine, the examiner holds both of the child’s knees and gently adducts one hip and pushes posteriorly. B: When the examination is positive, the examiner will feel the femoral head make a small jump (arrow) out of the acetabulum (Barlow’s sign). When the pressure is released, the head is felt to slip back into place. (Reprinted with permission from Tachdjian’s Pediatric Orthopaedics, 4th Edition, edited by John A. Herring.)

FIGURE 215-2. The Ortolani test for developmental dislocation of the hip in a neonate. A: The examiner holds the infant’s knees and gently abducts the hip while lifting up on the greater trochanter with two fingers. B: When the test is positive, the dislocated femoral head will fall back into the acetabulum (arrow) with a palpable (but not audible) “clunk” as the hip is abducted (Ortolani’s sign). When the hip is adducted, the examiner will feel the head redislocate posteriorly. (Reprinted with permission from Tachdjian’s Pediatric Orthopaedics, 4th Edition, edited by John A. Herring.)

In the infant (greater than 3 months of age), more specific physical exam findings of the dislocated hip will appear, such as limited hip abduction and a more proximal location of the greater trochanter. The Galeazzi sign, highly suggestive of developmental dysplasia of the hip, is a relative shortening of the thigh when comparing the height of the knees with both hips flexed 90°. With a unilateral dislocation, the thigh will be foreshortened, resulting in additional thigh folds on the affected side. However, extra thigh folds are a normal variant and do not necessarily indicate a hip dislocation. Limitation of abduction, the most reliable sign of a dislocated hip, is best appreciated by abducting both hips simultaneously with the child on a firm surface. The dislocated side will have a distinct reduction in abduction as compared to the healthy side.

The evaluation of the infant with bilateral hip dislocations can be difficult. There may be symmetric abduction and similar thigh lengths with the Galeazzi test. The Klisic test is performed by placing the middle finger on the greater tro-chanter and the index finger on the anterior superior iliac spine. Normally, an imaginary line drawn between the two fingers will point at the umbilicus. If the hip is dislocated, the line will point between the umbilicus and the pubis.

The physical findings in a child of walking age with a unilateral dislocated hip may include decreased abduction of the affected hip, a positive Klisic test, a positive Galeazzi sign, a limp, and a leg length discrepancy. A walking patient with bilateral hip dislocations often presents only with a complaint of increased lumbar lordosis (sway back) secondary to bilateral hip flexion contractures but may also have a lurching gait on both sides.

The neonate’s femoral head and acetabulum are primarily cartilaginous, making conventional radiographs difficult to interpret. Ultra-sonography visualizes the soft tissue structures of the hip and the relationship of the femoral head and acetabulum very well.6 The AAP recommends ultrasonography for female infants either carried breech or with a positive family history for developmental dysplasia of the hip.1 An infant with a positive Ortolani or Barlow sign does not require an immediate ultrasound but should be referred to a pediatric orthopedic surgeon for treatment. Plain radiographs become useful at 3 to 6 months of age when the femoral head begins to ossify.

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

The Pavlik harness (Fig. 215-3) is the first choice of treatment for patients less than 6 months with an unstable hip or hip dislocation.7 The harness should hold the hip in more than 90° of flexion. If the hip cannot be placed into this position, the treatment will fail. The hip, however, does not have to be reducible at the time of the examination to be successfully treated with the harness. The child should be evaluated weekly with clinical and ultrasound exams to document the reduction of the femoral head. If the femoral head is not reduced within 3 to 4 weeks, the harness is abandoned. If the hip successfully reduces, the harness is continued for an additional 6 to 12 weeks.

For the child between 6 months and 2 years of age who presents with a dislocated hip or who has failed initial harness treatment, the goal of treatment is to obtain and maintain a concentric reduction of the hip without damaging the femoral head. This is most often done with an adductor tenotomy, closed reduction and application of a spica cast in the “human position,” or by an open reduction of the hip. The child who presents over 2 years of age with a dislocated hip usually requires an open reduction, a femoral shortening osteotomy, and a pelvic osteotomy to correct the persistent femoral and acetabular bony deformities. Follow-up to skeletal maturity is essential as persistent acetabular dysplasia may be present despite the perfect execution of prior treatments at any age. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head is the most significant complication associated with the treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip and can occur as the result of any nonoperative or operative treatments.

LEGG-CALVÉPERTHES DISEASE

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease (LCPD), a common cause of avascular necrosis of the femoral head in children, is a condition in which the vascular supply to part or all of the femoral head is disrupted leading to the cessation of femoral head growth and increased femoral head density. The dense bone is subsequently resorbed and replaced by new bone. However, during this process the mechanical properties of the femoral head are altered, typically resulting in enlargement and flattening of the femoral head. Despite being recognized as a distinct entity a century ago, the exact etiology of LCPD is still unknown and is probably multifactorial. Factors that have been associated with the etiology of LCPD include coagulopathy, trauma, hereditary influences, hyperactivity or attention deficit disorder, and environmental factors, including exposure to cigarette smoke. These may work in combination in a “predisposed child” with certain growth and developmental abnormalities.8-12 Low birth weight, short stature for age, and delayed bone age relative to chronological age early in the disease process are common findings. However, how these findings relate to the pathogenesis of the disease is still uncertain.

LCPD can be diagnosed between 18 months of age and skeletal maturity but is most prevalent between 4 and 12 years of age. The disease is 4 to 5 times more likely to develop in boys than girls, more common in whites and those of Asian descent, and rare in African Americans and Native Americans. African Americans presenting with clinical and radiographic signs of LCPD should undergo evaluation for an underlying hemoglobinopathy. Bilateral disease occurs in 10% to 12% of patients but is typically not symmetric or concurrent. A patient with bilateral, symmetric avascular necrosis should be evaluated for other systemic conditions such as hypothyroidism, an epiphyseal dysplasia, Gaucher disease, sickle cell disease, and steroid medication use.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree