Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

INTRODUCTION FOR THE NEONATOLOGIST

The term developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) indicates a spectrum of pathologies from stable acetabular dysplasia (femoral head stable in hip socket but socket is shallow) to “located” hips that are unstable (femoral head can be moved in and out of the confines of the acetabulum), to frankly dislocated hips in which there is a complete loss of contact between the femoral head and acetabulum. Congruent reduction and stability of the femoral head are necessary for normal growth and development of the hip joint. The natural history of DDH is variable: Acetabular dysplasia often resolves spontaneously. Unstable or dislocated hips may reduce spontaneously, but some will require treatment to normalize.

Whether dysplastic, dislocatable, or completely dislocated, DDH in the newborn period is pain free and asymptomatic. However, failure to diagnose this entity can have drastic results. In cases that have persistent dysplasia or untreated dislocation, infants have a significantly increased risk of developing precocious arthritis with moderate-to-severe hip pain as young adults.1,2 This pain can be debilitating. Early detection and treatment of DDH are therefore important in avoiding the devastating sequelae of a late diagnosis. Given the complexity and acuity of patients in the neonatal intensive care unit and the silent nature of this disorder, DDH can easily be overlooked in this patient population. Fortunately, the diagnosis of DDH requires only modest vigilance to detect in the majority of cases.

INCIDENCE AND ETIOLOGY

Developmental dysplasia of the hip occurs in 11.5 of 1000 infants, with 1–2/1000 having frank dislocations.3,4 Although all children should be screened for DDH by physical examination, there exist particular risk factors for DDH that warrant closer scrutiny. These risk factors include a positive family history (boys, 9.4/1000; girls, 44/1000); breech presentation (boys, 26/1000; girls, 120/1000); and the presence of an unstable hip examination at birth. The left hip alone is affected in 60%, the right hip in 20%, and both hips in 20% of infants.4

Despite newborn screening programs, 1 in 5000 children will have a dislocated hip detected at 18 months of age or older.5 It is important to appreciate that not all dislocated hips are present at birth, and not all hips dislocated at birth are detectable in the newborn period.

Dislocations can be divided into two groups: syndromic and typical. Syndromic dislocations are most frequently associated with neuromuscular conditions such as myelodysplasia and arthrogryposis or with dysmorphic syndromes such as Larsen syndrome. These abnormalities probably occur between week 12 and week 18 of gestation.3 Typical dislocations occur in otherwise-healthy infants in the third trimester or postnatal period. Syndromic dislocations are often fixed and nonreducible and require orthopedic referral. The rest of this chapter deals only with typical dislocation.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

There are no pathognomonic signs of a dislocated hip. The physical examination requires patience on the part of the examiner and a quiet, calm infant/patient. This may be facilitated by having the baby feed from a bottle and dimming the room light. Evaluation for asymmetry of hip movement is an important key to the evaluation for DDH, although asymmetry may not be evident in bilateral dislocations. The presence of asymmetric thigh folds may be indicative of dislocatable hip but is often present in unaffected children and can be seen in up to 20% of normal infants. Asymmetric thigh folds in the absence of other physical examination findings should be considered a nonspecific finding and does not require further imaging or workup. Presence of asymmetric flexed hip abduction is suggestive of a dislocation, as is a Galeazzi sign (Figure 63-1). The Galeazzi sign is elicited with the baby placed supine on an examining table so that the pelvis is level, and the hips and knees are flexed to 90°. With the baby’s hips in neutral abduction, the examiner determines if the knees are at the same height. If one femur appears shorter, the hip may be dislocated posteriorly. Limited hip abduction in babies older than 12 weeks is the most reliable examination finding suggestive of DDH. Adduction of 30° and abduction of 75° should be possible in most newborns. Hip abduction is performed with the hip in flexion. Side-to-side variations should be noted. Each of these signs, individually or in combination, may serve to increase the index of suspicion of the examiner and lower the threshold for further diagnostic studies or referral to a pediatric orthopedist.

FIGURE 63-1 The Galeazzi sign. The left femur appears shorter than the right. This is an indication that the left hip may be dislocated. (Reproduced with permission from the Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy, edited by Robert Porter. Copyright 2012 by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co, Inc, Whitehouse Station, NJ. Available at http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/. Accessed December, 2014.)

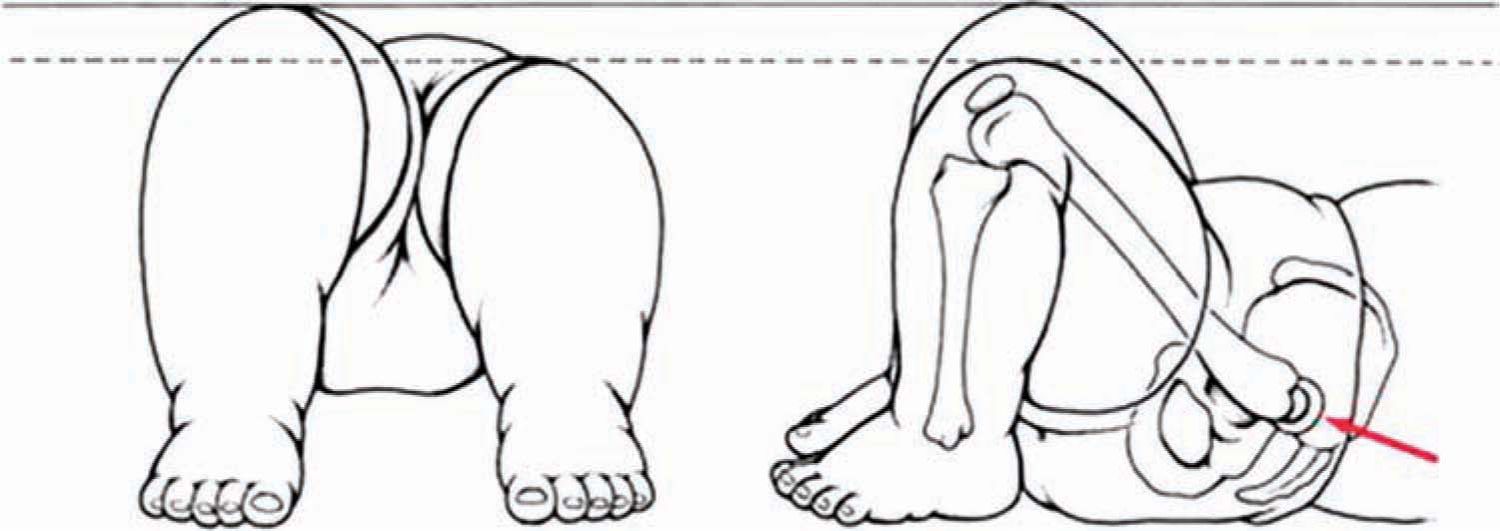

There are two common ways of assessing hip stability in the newborn. The Ortolani test (Figure 63-2) is performed, one leg at a time, with the calm newborn supine on the examining table. The index and middle fingers of the examiner are placed along the greater trochanter; the thumb is placed on the medial aspect of the thigh. The pelvis is stabilized by placing the thumb and ring or long finger of the opposite hand on top of both anterior iliac crests simultaneously. Alternatively, the opposite thigh may be held in the same manner as the examined side while the hip is held in abduction. The hip is flexed to 90° and gently abducted while the leg is lifted with the hip in neutral external/internal rotation. A palpable “clunk” is felt as the dislocated femoral head reduces into the acetabulum. This finding is reported as the Ortolani sign (positive result on the Ortolani test).

FIGURE 63-2 The Ortolani sign. With the hip flexed to 90° and the leg gently abducted, if the hip is dislocated initially, reduction of the hip with abduction will produce a palpable clunk. (Reproduced with permission from Guille JT, Pizzutillo PD, MacEwen GD. Development dysplasia of the hip from birth to six months. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8(4):232–242.)

The Barlow test (Figure 63-3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree