Desquamating and Hyperkeratotic Disorders in the Neonatal Period

INTRODUCTION

In the neonatal period, disorders may sometimes present with hyperkeratosis and desquamation of the skin. The differential diagnosis for hyperkeratosis and desquamation in the neonatal period is broad and includes infectious, genetic, inflammatory, immunodeficiency, and metabolic causes. Rarely, these disorders may also present with erythroderma, or generalized skin erythema affecting at least 90% of the body surface.1 Scaling is a commonly associated symptom of erythroderma. Although the frequency of hyperkeratotic and desquamating disorders in the newborn period is unknown, the incidence of neonatal erythroderma has been estimated2 to be 0.11%.

These skin changes are nonspecific and do not indicate any particular diagnosis; thus, this constellation of findings may prove to be challenging both diagnostically and therapeutically. Clinical clues and diagnostic testing can be of great importance in reaching a diagnosis. Management can be extremely challenging, as often these neonates are quite ill. Both general management principles and treatments aimed at the specific disorder are vital to the care of these babies. Despite advanced care, the mortality rate3 in these patients, particularly those with erythroderma, can approach 15%. Factors contributing to this high mortality rate are large ratio of surface area to body mass with subsequent increased transepidermal fluid loss and increased susceptibility to infection.

INFECTIOUS CAUSES

Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS), which has also been called pemphigus neonatorum, is a toxinmediated blistering condition of the skin that primarily affects infants and young children. Neonatal SSSS and outbreaks in neonatal intensive care units are also known to occur.4 The more localized form of the disease is called bullous impetigo; the more widespread counterpart with generalized involvement is called SSSS.

The initiating staphylococcal infection may start with impetigo that is localized, most commonly in the nares, eyes, or umbilicus in neonates. Toxins produced by the Staphylococcus aureus bacteria, exfoliative toxins A and B, are released by the bacteria. These toxins target desmoglein 1, which is a protein vital in epidermal cell-to-cell adhesion.5 Infants and young children are most susceptible because of a lack of protective antibodies and immature renal clearance of these toxins. Clinical manifestations are that of initial facial and perioral erythema followed by superficial blisters that may progress rapidly to generalized erythroderma and the appearance of “wrinkled” skin. This is often more noticeable around the mouth and in skin folds.4 Affected infants are usually fussy.

Other disorders that may be considered in the differential diagnosis are few, although it may be mistaken for Kawasaki disease, viral exanthema, drug eruption, or toxic epidermal necrolysis. Many of these do not usually occur in the neonatal period.

Often, SSSS is a clinical diagnosis. Any cultures taken from the bullae are expected to be sterile as blisters are directly caused by the toxin and not the bacteria itself. Biopsy can be performed but is rarely required. Histopathology will show an intraepidermal split above or below the granular layer with minimal inflammation.5

Management of SSSS is with antistaphylococcal intravenous antibiotics. Supportive care for pain control, careful handling of the patient’s skin, and prevention of secondary infection is often required. Bland emollients such as Aquaphor or white petrolatum should be used to areas of denuded skin. Close attention to fluid balance and body temperature is critical, particularly in the neonatal period.

Overall prognosis for SSSS is quite good. The most common complications are rare and include cellulitis, sepsis, and pneumonia, with a 3% mortality rate.5 The skin will usually heal rapidly within 2–3 weeks without scarring. Desquamation of the palms and soles can continue for an additional 2–3 weeks after the initial disease. Long-term follow-up is usually not needed.

Congenital Cutaneous Candidiasis

Congenital cutaneous candidiasis is a rare condition. Less than 100 cases have been reported in the literature.6 Although 20%–25% of pregnancies are complicated by vaginal candidiasis, less than 1% of these will proceed to ascending infections involving the placenta and amnion.6 Preterm infants are more susceptible to the presence of the disease, with increased risk of disease severity, in large part because of immature keratinization of the skin.

When congenital candidal infection occurs, small erythematous macules, papules, and pustules erupt within the first week of life. These may then become confluent and progress to exfoliative erythroderma.7 Nail dystrophy may be present.8 The oral cavity and diaper area can be spared. There can be severe systemic involvement, especially in premature or small-for-gestational-age neonates.

Other infectious skin diseases may present similarly, including SSSS, herpes simplex virus infection, varicella zoster virus infection, and syphilis. Neonatal blistering skin conditions such as epidermolysis bullosa, congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma (CIE), and incontinentia pigmenti may also be considered. Additional benign considerations include neonatal pustular melanosis and miliaria. However, neonatal candidiasis is usually acquired from the birth canal, develops after the first week of life, and tends to involve the intertriginous areas, including the diaper area. Erythroderma is not typical of neonatal candidiasis.

Diagnosis of congenital cutaneous candidiasis can be made at the bedside by demonstrating spores and pseudohyphae on skin scraping of a pustule. Biopsy of the skin may also be performed, demonstrating fungal elements in the stratum corneum, but is often unnecessary.9

Any neonate who has signs of systemic candidiasis should be pan cultured. Full-term infants without systemic disease can usually be treated successfully with topical antifungal therapy. Neonates who are preterm and those who are systemically ill will require parenteral antifungal therapy.

Neonates with congenital candidiasis limited to the skin and without systemic symptoms do well with quick resolution of skin findings without sequelae. Neonates with systemic infection have a much more guarded prognosis, particularly those who are less than 1 kg. These infants have a high mortality rate6 of up to 40%. Otherwise, follow-up is not necessary after the infection is cleared and the skin normalizes.

ICHTHYOSES

Nonsyndromic Ichthyoses

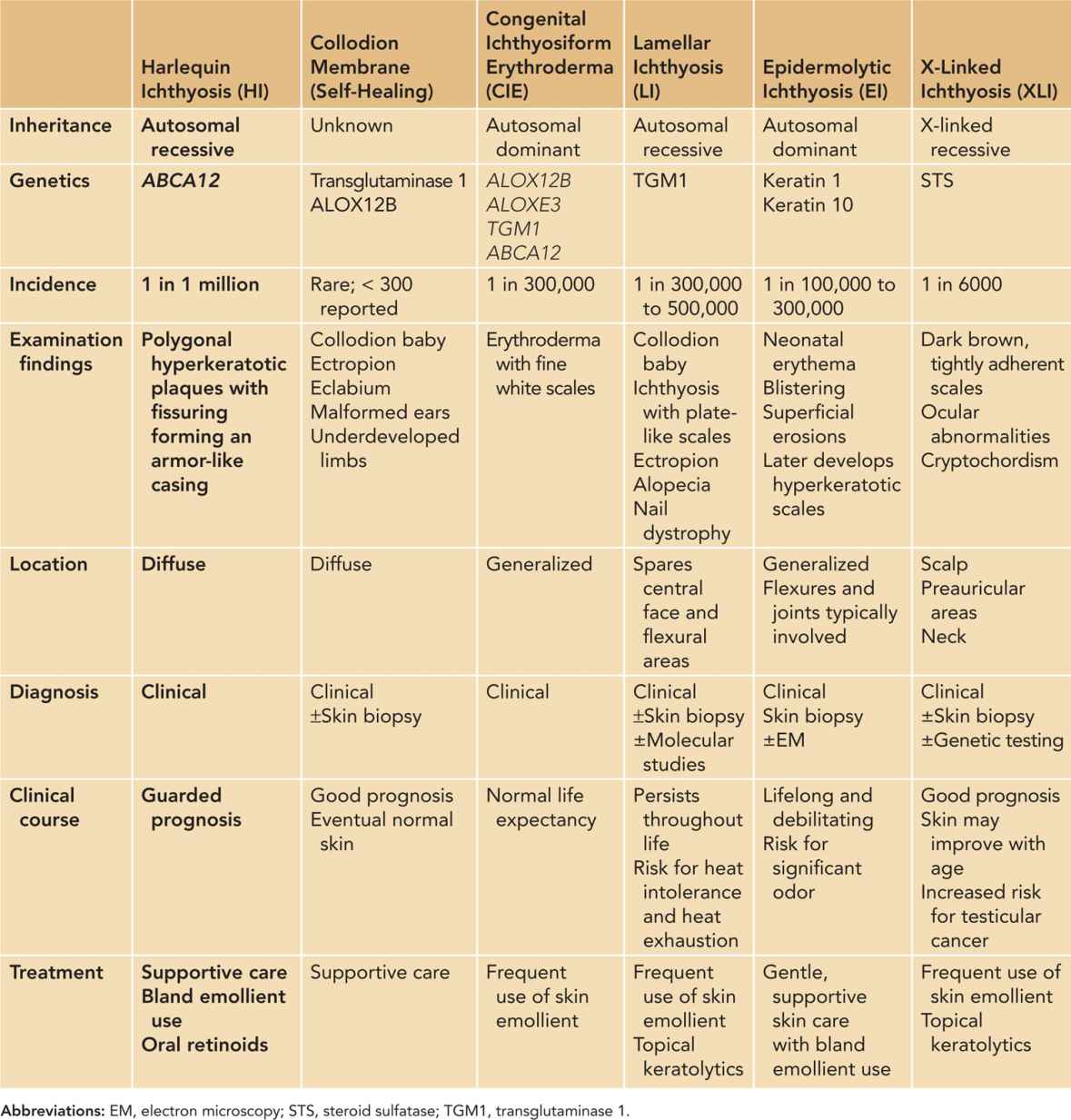

The ichthyoses (Table 66-1) are a heterogeneous group of disorders of abnormal cornification that results in scaly skin. Many of these disorders present in the neonatal period or early childhood. The nonsyndromic ichthyoses are diseases that are primarily limited to the skin and do not have significant systemic involvement.

Self-Healing Collodion Membrane

Rarely, a neonate may be born with a collodion membrane. The condition generally cannot be detected in utero, and diagnosis is therefore usually made at birth. A collodion baby has a “membrane” covering the entire body that is smooth and taut with a shiny surface. The skin is thick and inelastic with frequent contractures of the joints and eversion of the mouth and eyelids. This sign can signify the presence of a significant underlying skin disorder but may also be seen in a neonate who will not go on to develop a skin disorder, thus termed a “self-healing” collodion baby. The presence of a collodion membrane is rare, with approximately 300 cases reported in the literature (Figure 66-1). Approximately 10%–20% of these babies end up with clear skin.10

FIGURE 66-1 Self-healing collodion membrane baby. On presentation, collodion membrane is seen with eventual skin desquamation.

The pathogenesis of the self-healing collodion baby has yet to be fully understood. Several genes, including the transglutaminase 1 (TGM1) gene and ALOX12B, have been implicated but not definitively linked.

The differential diagnosis for the underlying cause of a collodion baby also includes the various types of congenital ichthyoses, namely, CIE, lamellar ichthyosis (LI), epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EHK), and Sjogren-Larsson syndrome (SLS).

Skin biopsy can aid with diagnosis of an underlying congenital ichthyosis; however, no diagnostic tests are necessary in diagnosing a self-healing collodion baby. Self-healing collodion baby is a diagnosis that is made with clinical observation.

Collodion babies are at high risk for increased transepidermal water loss, electrolyte imbalance, temperature instability, and infection.5 Supportive care with specific attention to maintaining hydration and fluid and electrolyte balance, controlling temperature, and vigilance for infection is important. Keratolytic agents should never be used. Light emollients and wet compresses can aid in peeling of the membrane skin. Ophthalmologic care should be sought to manage eversion of the eyelids. Oral retinoids can be considered for severe collodion babies whose shedding is delayed beyond 3 weeks.

Self-healing collodion babies have a good prognosis with essentially normal skin after the neonatal period. Shedding of the collodion membrane is usually complete within 3 weeks but can sometimes take longer.11 Follow-up is not necessary after skin normalization.

Congenital Autosomal Recessive Ichthyosis

Autosomal recessive (AR) ichthyosis is an umbrella term that encompasses CIE, LI, and harlequin ichthyosis (HI).12

Congenital Ichthyosiform Erythroderma

Congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma is also a frequent cause of collodion membrane; in fact, nearly 50% of collodion membrane babies go on to develop features consistent with CIE.11 Although the true incidence of CIE is unknown, it is likely underreported as the features can be mild and subtle in some patients.

The most common mutations involved in the development of CIE are in the ALOX12B and ALOXE3 genes. Also involved, but less commonly, are mutations in tissue TGM1 and ABCA12. At times, a genetic mutation cannot be found. If a collodion membrane is present at birth, on shedding of the membrane, erythroderma with fine white scales in a generalized distribution is noted. If there is no collodion membrane, the erythroderma and fine white scales usually develop in the first few weeks of life. Patients’ disease ranges in severity.

Lamellar ichthyosis and other congenital ichthyoses can be considered in the differential diagnosis. Diagnosis is usually made on clinical grounds. Skin biopsy may be minimally helpful as findings are not specific. Genetic testing is usually not indicated but useful.

Hydration of the skin is necessary, with regular bathing followed by a good skin moisturization regimen. Petrolatum-based emollients should be used. There may be increased absorption of ingredients that may be added to moisturizers; thus, caution must be used when selecting an emollient. Referral to the Foundation for Ichthyosis and Related Skin Types (FIRST) can be a helpful resource for families.13

The prognosis for patients with CIE may vary depending on phenotype. Minimally affected patients may be able to live as “normal” children, while more severely affected patients will need intensive care of their skin on a daily basis. Life expectancy is normal. Periodic monitoring by a dermatologist may be necessary depending on the severity of disease.

Lamellar Ichthyosis

Lamellar ichthyosis is felt to be on a clinical spectrum with CIE. It has an incidence12 of 1 in 300,000 to 500,000. Approximately 20% of collodion babies have underlying LI.11

Lamellar ichthyosis is most often caused by mutations in TGM1, which encodes an enzyme responsible for the integrity and function of the stratum corneum. Patients with LI have thick plate-like scales covering much of the cutaneous surface, most pronounced on the face and lower legs.5 Blockage of the eccrine glands by hyperkeratosis of the skin leads to subsequent diminished ability to sweat and resulting heat intolerance and hyperthermia. Scalp alopecia and ectropion of the eyelids are common features. Nail dystrophy can be present.

The scaling of X-linked ichthyosis (XLI) may be similar in appearance but it is seen in males and should not have associated features of alopecia, with ichthyosis usually sparing the central face and flexural areas.

The diagnosis of classical LI is primarily clinical. Biopsy results from skin are nonspecific, and genetic testing is usually not necessary.

Hydration and moisturization of the skin are necessary in all patients. Topical retinoids can be helpful in reducing scaling, as can other keratolytics, but these should not be used in the neonatal period. Low-dose oral retinoids may also be used in some patients as oral retinoids have been shown to upregulate TGM1 activity. Careful attention must be paid to the eyes, with continued corneal lubrication and involvement by ophthalmology.5 Counseling should be provided to families to educate and prevent heat exhaustion, particularly those that live in hot and humid climates. Referral to FIRST can be helpful for families.13

Most patients have significant difficulty with the thickness of scale on their skin and are often limited in their physical activity. There are also significant psychosocial implications and morbidity. Close follow-up with a dermatologist should be maintained.

Harlequin Ichthyosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree