Dental Occlusion and Its Management

Richard Bruun and Sivabalan Vasudavan

Dental occlusion is the term used to describe the relationship of the maxillary and mandibular teeth to each other when in contact and the relationship of the teeth to one another within each jaw. The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry “recognizes the importance of managing the developing dentition and occlusion and its effect on the well-being of children, adolescents, and adults.” Such management requires the appropriate and timely diagnosis of any developing malocclusion and the ability to either provide the proper treatment or to refer the patient to the appropriate specialist for treatment, with the ultimate goal of obtaining a stable, functional, and esthetically pleasing occlusion in the permanent dentition.1

The pediatrician is uniquely positioned to clinically detect many malocclusions in the course of his or her routine medical practice. This chapter covers the stages of dental development and normal occlusion and provides basic knowledge regarding the most common types of malocclusions seen in children. A more detailed description of relevant oral and dental anatomy is provided on the textbook DVD and in eFigure 376.1  .

.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE DENTITION

The normal sequence of tooth formation is outlined in eTable 376.1  . The earliest sign of tooth formation is seen at about the sixth week of embryonic life. The tooth buds of the primary teeth develop at 10 specific sites in the developing maxilla and mandible. The 20 succedaneous permanent teeth develop beneath the primary teeth while the permanent molars develop distally in sequential order. Calcification of the primary teeth begins at about 4 months in utero, and the enamel of all crowns is completed by 10 months after birth. The permanent teeth begin to calcify with the first molar around the time of birth, and the process is complete for all the teeth, with the exception of the third molars, by the seventh to eighth year of life.

. The earliest sign of tooth formation is seen at about the sixth week of embryonic life. The tooth buds of the primary teeth develop at 10 specific sites in the developing maxilla and mandible. The 20 succedaneous permanent teeth develop beneath the primary teeth while the permanent molars develop distally in sequential order. Calcification of the primary teeth begins at about 4 months in utero, and the enamel of all crowns is completed by 10 months after birth. The permanent teeth begin to calcify with the first molar around the time of birth, and the process is complete for all the teeth, with the exception of the third molars, by the seventh to eighth year of life.

In both the primary and permanent dentitions, the process of tooth eruption correlates with root development. When the crown emerges through the gingiva, the root usually comprises one half to two thirds of its final length. Eruption continues until the antagonist in the opposing jaw is contacted in occlusion. As tooth wear occurs throughout life, eruption continues but at a much reduced rate, keeping the teeth in occlusion. The primary cause of tooth eruption has not been definitively identified.

Exfoliation of the primary teeth is a normal physiological process that takes place as root development occurs in the permanent successors beneath them. The eruptive process stimulates the formation of osteoclasts, which results in the resorption of the roots of the primary teeth and their subsequent loss. Girls generally precede boys in the eruption of their permanent teeth.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE DENTAL ARCHES AND THE OCCLUSION

THE PRIMARY DENTITION

THE PRIMARY DENTITION

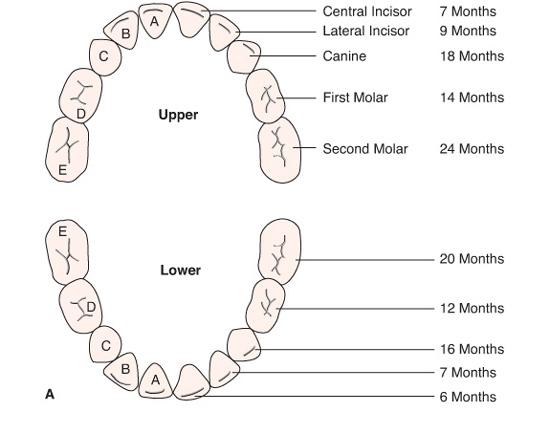

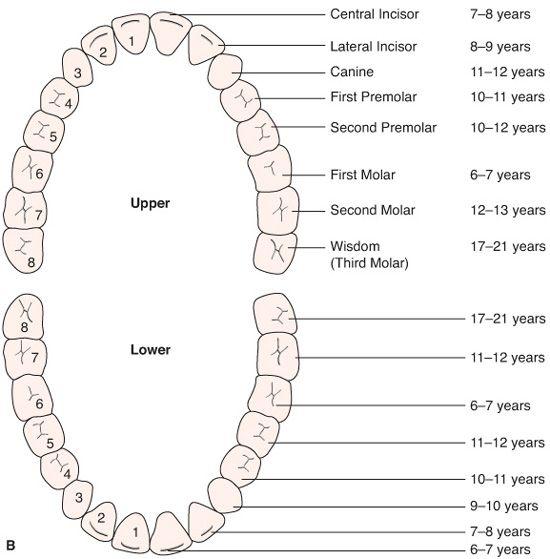

The primary (deciduous) dentition is comprised of 20 teeth, which begin to erupt at approximately 6 months of age and usually complete their eruption before the age of 3 years1 (Fig. 376-1A). In each quadrant, from anterior to posterior, there is a central incisor, a lateral incisor, a canine, and first and second molars. The timing of eruption varies considerably from child to child, but the sequence of eruption is usually as follows: central incisor, lateral incisor, first molar, canine, and second molar with the mandibular teeth erupting somewhat earlier than the maxillary teeth and bilateral symmetry usually the case. Ideally there should be spacing present between all of the teeth, although any space present between the posterior teeth usually closes prior to the eruption of the first permanent molar. Absence of spacing in the primary dentition suggests a greater than 50% probability of crowding in later stages of the dentition.2

Normal occlusion is characterized by maxillary and mandibular teeth that are related properly to each other in the sagittal, transverse, and vertical dimensions. The maxillary incisors and canines are positioned slightly forward of the mandibular incisors (normal overjet with no anterior crossbite), and the maxillary molars are positioned so that their buccal cusps occlude slightly to the outside of the mandibular molars and their palatal cusps occlude onto the center of the biting surface of the mandibular molars (normal buccal overjet with no posterior crossbite). Furthermore, there should be only a mild to moderate amount of vertical overlap of the maxillary and mandibular incisors (normal overbite). The midlines of the maxillary and mandibular dentitions should be approximately coincident with each other and with the facial mid-line (as approximated by the center of the philtrum), and there should be no significant shifting of the mandible laterally or anteriorly as the teeth come into contact (Fig. 376-2).

The relative position of the jaws, and therefore the occlusion, is reflected in the profile, which is also affected by the position of the teeth and by the soft tissues themselves. It is normal for the profile to be convex during the primary dentition stage of dental development, with this convexity usually decreasing during the subsequent stages as a result of greater forward growth of the mandible when compared with the maxilla (consistent with the overall cephalocaudal growth gradient).3

THE MIXED DENTITION

THE MIXED DENTITION

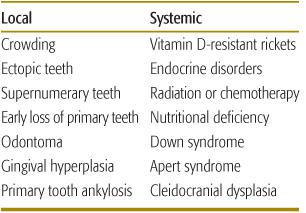

The mixed dentition is characterized by the presence of both primary and secondary teeth (eFig. 376.2  ), beginning with the eruption of the permanent incisors and molars between 6 and 7 years of age (Fig. 376-1B). The central incisors usually erupt prior to the lateral incisors, with the mandibular teeth erupting before the maxillary teeth. If any tooth has erupted normally and the contralateral tooth is delayed in eruption by greater than 6 months’ time, the patient should be referred for evaluation. Delayed tooth eruption is the most commonly encountered deviation from normal eruption time and may indicate systemic problems such as endocrine disorders or Down syndrome. Most frequently, delayed tooth eruption is the result of local factors such as the presence of a supernumerary tooth or ectopic eruption4 (Table 376-1).

), beginning with the eruption of the permanent incisors and molars between 6 and 7 years of age (Fig. 376-1B). The central incisors usually erupt prior to the lateral incisors, with the mandibular teeth erupting before the maxillary teeth. If any tooth has erupted normally and the contralateral tooth is delayed in eruption by greater than 6 months’ time, the patient should be referred for evaluation. Delayed tooth eruption is the most commonly encountered deviation from normal eruption time and may indicate systemic problems such as endocrine disorders or Down syndrome. Most frequently, delayed tooth eruption is the result of local factors such as the presence of a supernumerary tooth or ectopic eruption4 (Table 376-1).

FIGURE 376-1. A: Schematic of the primary dentition with eruption times. B: Schematic of the permanent dentition with eruption times.

Once the permanent incisors and molars have completely erupted, there is usually a period of 2 to 3 years when no exfoliation of deciduous teeth or eruption of secondary teeth is observed. The transition to the permanent dentition begins between 9 and 11 years of age and continues to approximately age 14. The sequence of eruption is different in the mandible and the maxilla. In the mandible, the pattern is usually canine, first premolar, second premolar (premolars or bicuspids replace the primary molars), and second molar. In the maxilla, the sequence is usually first premolar, canine, second premolar, and second molar. It is during this stage of development that one or both maxillary canine teeth may encounter difficulty in erupting. Ectopic maxillary canines occur in 1% to 3% of the population and can cause the resorption of the roots of the neighboring permanent teeth (usually the lateral incisors), possibly even resulting in the complete loss of a tooth or teeth6 (eFig. 376.3  ).

).

FIGURE 376-2. Normal primary dentition.

The spaces between the anterior teeth that may have been present in the primary dentition are largely consumed when the larger permanent incisors erupt (“incisor liability”). Space may remain between the maxillary central incisors, where a thick labial frenum (Fig. 376-3) can persist and help to prevent its normal closure (83% of the patients with a diastema at 9 years of age do not have one at age 16).7,8 Importantly, the space available to accommodate the teeth from first permanent molar to first permanent molar (arch circumference) increases only marginally in the maxilla and actually decreases in the mandible during the mixed and permanent dentitions. Skeletal growth does not result in more space for the teeth in this region but does help to accommodate teeth posterior to the first permanent molars.9 The permanent canines and premolars are usually slightly smaller in size than the primary teeth that they replace (leeway space). Managing this space in the late mixed dentition may be important in the treatment of crowding and the ability to treat such crowding without extracting permanent teeth.10

Table 376-1. Common Factors and Conditions Associated with Delayed Tooth Eruption

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree