Crying in Infants

Ronald G. Barr and Takeo Fujiwara

In the last 30 years, clinical and nonclinical studies, including both experimental and naturalistic observational ones, have provided a more complete understanding of the nature and functions of early crying and its clinical manifestations. This has led to a re-conceptualization of increased excessive crying and colic.1 Current evidence supports 2 concepts as important to our understanding of this behavior.

The first is that early increased crying in the first 4 months (including most cases of colic) is a manifestation of normal behavioral development rather than an indication of abnormalities in either the infant or their caregivers.2 Essential to this concept is that all infants manifest a similar pattern and similar forms of distress along a spectrum of quantity and intensity, from fussiness to inconsolable crying, or colic. Those infants at the higher end of the spectrum are more likely to present due to a clinical concern.2,3 Since virtually any illness will increase crying, a small number of infants (probably less than 5%) that present with crying complaints are also found to have abnormal cries and/or pathogenetic processes associated with this crying.3-5 However, these abnormalities are superimposed on a normal developmental increase in crying common to all infants. The vast majority (over 95%) of infants with increased crying and colic are healthy infants with normal behavioral development.

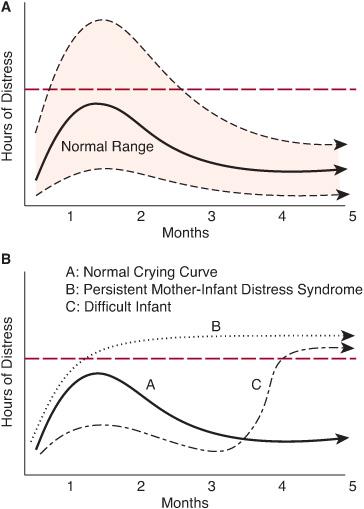

The second concept is that, developmentally, there are 3 primary age-related patterns of early increased crying (see Figure 83-1). The typical and most well-known pattern includes an increase in overall distress (fussiness, crying, and inconsolable crying together) that begins at about 2 weeks of age, peaks sometime in the second month, and then decreases by 3 to 5 months to lower and more stable levels. This pattern is typical of all normal infants, and the amounts vary widely among infants.2,6,7 However, in those in whom some defined threshold is exceeded (often called the Wessel criteria; crying for >3 hours per day, for >3 days per week, for >3 weeks2,8), this is most often referred to as typical colic. In the second pattern, crying increases into the second month but continues after 4 months at previously high levels, usually accompanied by loss of positive caregiver-infant interactions and continuing distress for both (see dotted line [B] in Fig. 83-1B). This pattern may occur in about 3% of infants.9,10 It has been referred to as persistent mother-infant distress syndrome to differentiate it from typical colic.9-11 In the third pattern, sustained crying increases begin after the first 4 months and persist into later months of the first year of life (see dotted line [C] in Fig. 83-1B). This pattern is usually typical of infants who are characterized as having “difficult temperaments”12,13 and may occur in about 3% of infants.13,14

Figure 83-1. A: Typical increase and then decrease pattern of distress in normal infants. Solid line represents modal pattern for the group; shaded area represents typical wide ranges of normal patterns. Horizontal red line represents typical arbitrary “cutoff” line for definitions of infants whose amounts of distress qualify them as infants with “colic” based upon Wessel’s criteria (crying for >3 hours per day, for >3 days per week, for >3 weeks). B: The modal pattern for normal infants is represented by solid line A; the typical pattern for infants with persistent mother-infant distress syndrome with dotted line B; and the typical pattern for infants with difficult temperament with dot-dash line C.

The distinction between typical colic in which the crying resolves and persistent crying after 4 months is not simply a question of age-related patterns. The evidence is now clear that in the absence of the possible consequences of infant abuse,15-17 the long-term prognosis for infants with typical colic is no different from the prognosis for those without.18,19 By contrast, for those with increased crying after 4 months of age, the risk of negative outcomes increases. Those outcomes include sleeping problems,19,20 eating disorders,20 parent-infant relationships,21 cognitive difficulties,22 and hyperactivity.23 The breadth of the negative outcomes suggests that early, persistent crying beyond 4 months may be a nonspecific index of later forms of dysfunction.

These 2 important concepts concerning the developmental patterns of early increased crying provide a framework on which a clinical approach to typical colic can be based.

CLINICAL DEFINITIONS AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Colic is best thought of as a syndrome comprising a cluster of behaviors presumed to represent a distinct condition. Clinical descriptions usually focus on 3 characteristic dimensions, parallel to crying in normal infants.18,25 First, crying usually clusters in the late afternoon or evening, peaks in the second month, and resolves by 3 to 4 months of age. Second, there are associated motor behaviors (eg, legs over abdomen, clenched fists), an atypical facial expression (eg, pain facies), gastrointestinal symptoms (eg, distention, gas, regurgitation), and lack of response to soothing (including lack of quieting with feeding). Third, the prolonged crying bouts are “paroxysmal,” beginning and ending without warning, and unrelated to events in the environment. Colic is variably defined,54 but the most widely used definition is the Wessel “rule of 3s”: crying more than 3 hours per day for more than 3 days per week for more than 3 weeks.8,25 Such quantitative definitions capture neither the quality nor the overlap with normal crying. They are helpful, but not sufficient, for clinical evaluation.

To reflect the range of crying complaints, it is more helpful to consider a spectrum of behavioral clusters for which a clear etiology may be demonstrable only for “organic” cases.18,25 Based on controlled studies, this spectrum could include the following:

1. Organic, crying with clear evidence for disease.

2. Wessel-plus crying, excessive crying that meets Wessel criteria is also accompanied by physical signs of hypertonia (eg, arched back, clenched fists, hypertonic arms/legs), crying bouts perceived as particularly intense or high pitched, or painlike behavioral signs of distress.

3. Wessel crying, crying that meets Wessel criteria for quantity with a typical diurnal rhythm, unsoothable bouts, and occasional pain facies and sometimes qualitatively different cries in infants who are otherwise normal;

4. Non-Wessel crying, crying that does not meet quantitative criteria for excessive crying in infants who may have qualitatively different (eg, sick-sounding) cries.

5. Normal concern, crying in which the pattern is typical, and the complaint results wholly from lack of information about typical crying characteristics at this age.

Estimated incidence varies by site (primary or referral), but all complaints together could include 40% to 50% of infants. Wessel and Wessel-plus crying together account for approximately one third of all complaints. Organic causes are demonstrated in 5% or less of all complaints 4,5,55

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The most basic concept for understanding early crying is that of the organization of infant behavior as a set of discontinuous and distinct modes, or states.2,56,57 Behavioral states have the following features:

1. Being self-organizing; that is, the characteristic behavioral clusters (eg, vocalizations, respirations, facial and motor activity) are constrained to occur together because of the organizational relations among the components.

2. Being stable over time (minutes rather than seconds).

3. Having qualitatively distinct reactions to stimuli depending on behavioral state (ie, the responses are state-specific and nonlinear).

During transitions between states, the organism is less well organized and less stable. In the Wolff classification of infant behavior,56 crying and awake activity represent behavioral states, and fussing represents a transition. Thus, intermittent crying vocalizations (fussing) can become incorporated into a state of the organism that is prolonged, self-sustaining, and resistant to soothing (crying), consistent with a colic bout in otherwise healthy infants. This may explain the resistance to soothing, because a soothing maneuver that is otherwise successful for unsustained whimpering or fussiness can fail if initiated during the crying state.2

Both internal and external stimuli (ie, physiological or behavioral) can act alone or together to enhance the stability of states or transitions to different states. Consequently, the typical characteristics of colic do not require that we posit etiologies that implicate pathophysiologic processes. As a result, cry/colic syndromes can and do occur in well infants in optimal caregiving contexts. It is more accurate to consider determinants of prolonged crying states rather than specific etiologies. These are briefly reviewed below.

MATURATION

MATURATION

Rapid growth and differentiation of the central nervous system is reflected in the reorganization of crying, waking, and sleeping behavioral states in the first 3 months after birth. Noncry wakefulness becomes increasingly stable, less disrupted by internal and external stimuli, and more responsive to psychologically significant stimuli such as human voice and face.2,57 These changes are reflected in longer, crying bouts in the first 2 to 3 months, after which noncry wakefulness becomes more stable.

NUTRIENTS AND GUT HORMONES

NUTRIENTS AND GUT HORMONES

Nutrients can both exacerbate and reduce crying. More than 20 potentially antigenic cow-milk proteins may be passed through formula or breast milk, may stimulate gastrointestinal hypersensitivity reactions, and may contribute to increased crying.3 However, results of controlled diet trials are mixed, especially among breast-fed infants; positive results are more likely in small, highly select samples of Wessel-plus infants who manifest additional gastrointestinal symptoms.3 Incomplete carbohydrate (especially lactose) absorption contributes to gas symptoms, but evidence that this affects crying is limited.3 Some have hypothesized that developmental changes in gut hormones and motility could contribute to prolonged crying.61

CAREGIVING BEHAVIORS

CAREGIVING BEHAVIORS

Behaviors such as carrying, frequent feeding, use of a pacifier, car rides, and close mother-infant proximity—all involving postural change, repetition, constancy, and/or rhythmicity—tend to maintain a noncrying state.3,57 Controlled evidence about infant massage does not support its usefulness.63 Behavioral modifications have mixed results when used as treatment in infants with well-established colic.3,64

DISEASES AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

DISEASES AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Almost any disease or illness, from minor to severe, provokes acute crying in infants. However, few infants before 4 months of age present with nonfebrile, nonacute coliclike syndrome due to organic disease. Although rare, there is good evidence that cow-milk protein intolerance, isolated fructose intolerance, maternal fluoxetine hydrochloride (Prozac) via breast milk, infantile migraine, and anomalous left coronary artery can present with a coliclike syndrome.3 Evidence for reflux esophagitis is weak (see Chapter 394).3 Of particular concern are those syndromes that may have no other symptoms or visible signs, such as shaken baby syndrome.65

ETIOLOGIC MYTHS

There are no differences in crying or colic incidence in breast-fed versus formula-fed infants,66-69 or in firstborn versus later-born infants.26 Changing from breast-feeding to formula-feeding does not reduce crying or colic.3 Wet diapers are not a cause of infant crying.57 There is no evidence that crying or colic is caused by responsive parenting. With the possible exception of clinically depressed parents, there is little justification for attributing increased crying to parental distress or personality.70

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

In the clinical setting, colic refers to crying problems that are presented as complaints and to a syndrome in which crying is the cardinal symptom. Regardless of etiology, colic complaints are a product of both infant behavior and parental tolerance. Prolonged crying with a tolerant parent will not present as colic, while mild crying with a less tolerant parent will.69 Predispositions that lower parental tolerance are

• Expectations of a happy infant and the reality of a crying one.

• Lack of explanation for the peak, unsoothability, and paroxysmal character of crying.

• Social pressure from spouses, parents, and friends.

• The postpartum tendency toward maternal emotional lability and depression.

• Fatigue accompanying sleep disruption.

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

The presentation of a crying complaint must be taken seriously regardless of the quantity of crying, because there are always 2 problems: the infant’s behavior and the parent’s tolerance for it. Crying has negative consequences for the infant if caregiver frustration exceeds the caregiver’s tolerance, the most important of which is shaken baby syndrome or abusive head trauma.1,15,16 The crying may indicate none to severe organic, behavioral, or psychological illness in the infant. Neglect of the complaint could lead to severe consequences such as abuse or even death.

There are 3 important tasks for the clinician presented with a crying complaint: (1) detecting organic disease if present, (2) managing the crying and the caregiver’s concern, and (3) providing appropriate follow-up. eFigure 83.1  presents an algorithm incorporating important decision points regarding these tasks. Acute presentation and/or febrile infants require an investigation for organic disease. Nonfebrile infants with persistent crying who are older than 4 months do not have colic syndrome. If they do not have organic disease, they may have persistent mother-infant distress syndrome, seen in high-risk infants in high-risk families where normal intuitive parenting has broken down (B in Fig. 83-1B); they may be temperamentally “difficult” infants (C in Fig. 83-1B); or they may meet criteria for dysregulated infants with generalized problems with crying, feeding, and sleeping.12

presents an algorithm incorporating important decision points regarding these tasks. Acute presentation and/or febrile infants require an investigation for organic disease. Nonfebrile infants with persistent crying who are older than 4 months do not have colic syndrome. If they do not have organic disease, they may have persistent mother-infant distress syndrome, seen in high-risk infants in high-risk families where normal intuitive parenting has broken down (B in Fig. 83-1B); they may be temperamentally “difficult” infants (C in Fig. 83-1B); or they may meet criteria for dysregulated infants with generalized problems with crying, feeding, and sleeping.12

If infants do present with coliclike syndrome, there are 5 warning clues that are more common, although not diagnostic, in infants with organic etiologies:71

• A cry described as “high pitched” from an infant who regularly arches his or her back (even during fussing bouts) and whose crying does not manifest a diurnal pattern (more in the afternoon and evening).

• Crying is not the only symptom or sign following a complete history and physical.

• A late onset of crying (ie, it begins in the third month), especially following a switch from breast-feeding to formula-feeding (suggesting cow-milk protein intolerance).

• Unusual and excessive crying persisting beyond 4 months (suggesting an organic cause).

• A diurnal rhythm and weight gain make disease less likely.

Infants who do not have organic clues but meet Wessel-plus criteria (< 10%) are candidates for a therapeutic diet trial (formula change to protein hydrolysate, or elimination of cow milk from mother’s diet). There is no indication to switch from breast-feeding to formula. This practice increases maternal perception of the “vulnerability” of the infant.72

A diet trial usually reduces but will not eliminate crying in infants less than 3 months of age. Infants should be followed until crying resolves. In those infants where a diet trial fails, an evaluation for other disorders that may cause distress is indicated. It is less important to diagnose colic than to assess its functional significance for the infant and the parents. This can be facilitated by sensitive interviewing, and assessment on more than one occasion. All caregivers should be asked whether

• the frustration is too great.

• they are no longer attracted to their infant because of the crying.

• they have depressive symptoms.

Diary recording of the infant’s behavior (including crying and fussing), feeding, and weight by the parents is helpful for both parents and clinicians. If symptoms are atypical of normal colic and crying, organic etiologies should be considered, but as discussed above, an organic etiology is found in < 5% of crying infants.

MANAGEMENT

Information should be provided to parents about the typical pattern and properties of early increased crying, lack of responsivity to soothing, and the excellent outcome.

Focusing parental anxiety is usually accomplished by discussing and ruling out other potential disease processes, involving parents in data gathering (eg, maintaining a diary), and removing the guilt of “bad parenting.”

Counseling the parents by discussing and modeling behaviors that encourage a state of alert wakefulness rather than crying is helpful. These include carrying or rocking the baby, responding promptly to signals from the infant, decreasing feeding intervals, and using a pacifier. The more frequently these measures are provided, the more likely they are to be effective. The use of swaddling for crying is not as effective as its use for sleeping.73

All parents should be instructed never to shake the infant when frustrated. Instead, parents should be encouraged to put the baby down in a safe place, walk away, calm themselves, and then return every 15 minutes to make sure their baby is well.

Environmental modifications capitalize on the responsiveness of infants to constant, rhythmic stimulation. The best modification is increased time and contact with the infant. Alternatives include music, car or stroller rides, and devices that produce a rhythmic motion. The practice of using washer or dryer vibrations requires secure placement of the infant seat to prevent injury to the infant from falling off the appliance. It is possible, though not yet demonstrated, that decreased exposure to tobacco smoke might reduce crying amounts.62 Short and predictable periods of respite for the primary caretaker are essential.

The only medication consistently demonstrated to be effective in randomized trials is dicyclomine hydrochloride.74,75 However, colic has been removed as an indication for its use because respiratory distress and apnea have been reported with its use.76 Antireflux medication for persistent crying is not shown to be effective.77 Cisapride has also been discontinued as a treatment because of cardiac arrhythmias.78 Similarly, despite widespread use,79 there is essentially no empirical support for the use of proton pump inhibitors in infants with typical colic.80 Simethicone, an antigas medication, has not been proven to have any effect on crying in appropriate multicenter trials.81 Although there is some interest in the possibility that probiotics might be useful, the evidence to date is only suggestive82 and does not generalize widely.83

NATURAL HISTORY AND PROGNOSIS

In most infants, the condition resolves by 3 months of age, but in about 30% of infants, it persists to 4, and occasionally 5, months of age. If it does not resolve, organic causes should be reconsidered. To date, there is no evidence of growth, developmental, health, or temperament sequelae in infants with typical colic.18 However, parents’ perception of their infants as “difficult” or of themselves as less effective caregivers is increased.67,72,84 Unresolved crying is more likely in families who are themselves at risk and who have an infant with colic (a “double hit”).11,18 In the absence of infant or parental illness, the outcome, including mother-infant interaction, is excellent.18

REFERENCES

See references on DVD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree