Craniofacial Disorders

Carrie Lyn Heike and Michael L. Cunningham

Malformations of the face and skull represent a large portion of structural malformations in humans. These malformations can carry significant morbidity and often require surgical management within the first few months of life. Many children with craniofacial malformations are managed by multidisciplinary teams that often include an audiologist, dietician, geneticist, neurosurgeon, nurse coordinator, pediatrician, oral and maxillofacial surgeon, orthodontist, otolaryngologist, plastic/reconstructive surgeon, social worker, and speech pathologist. This chapter presents the major types of craniofacial malformations, their classification, heredity, and suggested management.

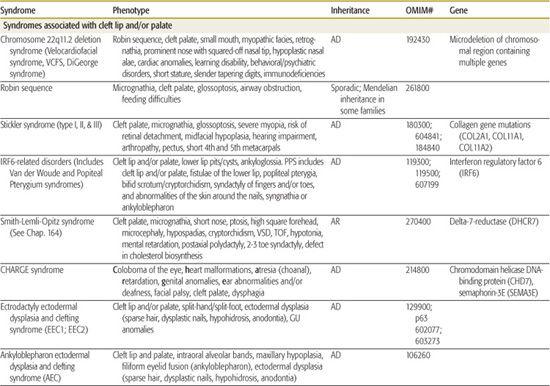

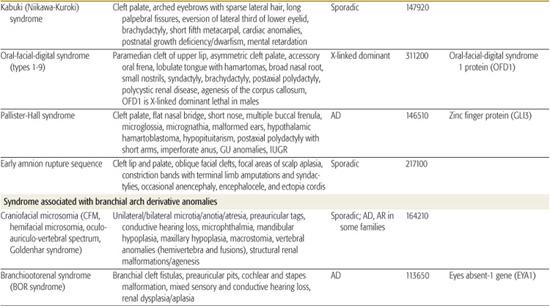

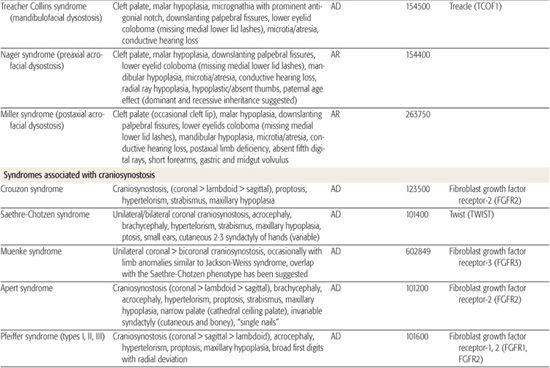

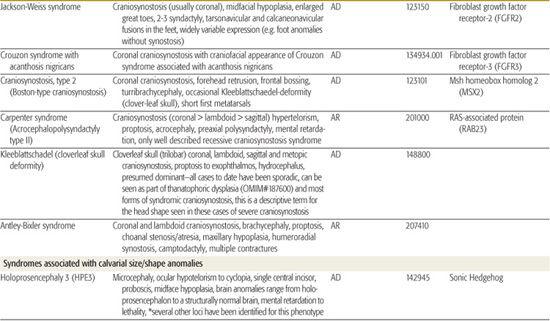

All children born with structural malformations of the face and/or skull require a careful physical examination, as many (20%) have associated anomalies that can involve multiple systems. When approaching the examination of a child with a craniofacial malformation, one needs to examine the entire child. The malformations of craniofacial structures can be so dramatic that the examiner overlooks other associated anomalies that deserve attention and may be associated with a unifying diagnosis. One approach is to leave the examination of the skull and face until the rest of the exam is complete. This allows the examiner to be sure that the other portions of the exam are normal. A list of common syndromes associated with each malformation type is presented in Table 177.1.

OROFACIAL CLEFTS

In this section, we focus on the most common forms of clefting, which include unilateral and bilateral clefts of the lip and/or palate.

CLEFT LIP AND PALATE

CLEFT LIP AND PALATE

Cleft lip and/or palate (CLP) represents one of the most common structural malformations in humans. The incidence of CLP varies depending on race (1/250 births in some Native American tribes, 1/350 Asian Americans, 1/700 Caucasian Americans, and 1/3000 in African Americans)1; however, these may be over estimations.2 Cleft lip and palate in combination is the most common form of orofacial clefting, with isolated cleft lip and isolated cleft palate having the relative following frequencies: 1:1.2:2.5 (CL:CP:CLP).

Inheritance of Cleft Lip and Palate

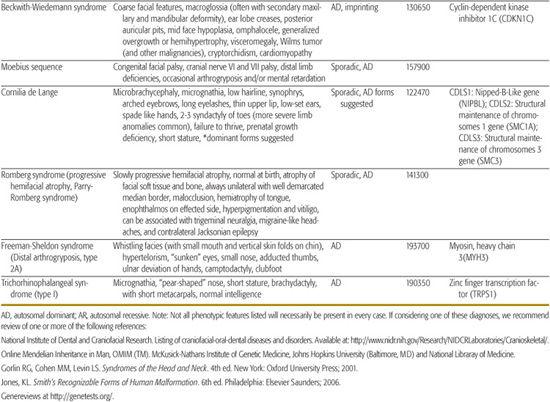

Although most cases of CLP represent sporadic (stochastic) events, recurrence in families with isolated CLP is well documented (Fig. 177-1). It is widely accepted that CLP is a multifactorial disorder that can have a hereditary component.3 If the first-born child of an unaffected couple has a CLP, the risk of the next child having a CLP is 3% to 4%. The recurrence risk for subsequent pregnancies is increased with the birth of additional children with orofacial clefts and family history (parents or grandparents) of clefting.2 In most cases we cannot discern sporadic from inherited forms of isolated CLP and thus statistically based risk estimates are used for genetic counseling. Peri-conceptual folate supplementation may reduce the risk of CLP in these “at risk” families, and some centers recommend folate supplementation for this reason. Isolated cleft lip and palate has been found to be associated with mutations in interferon regulatory factor 6 (IRF6)4 and Msx2, among other less commonly identified causes.5

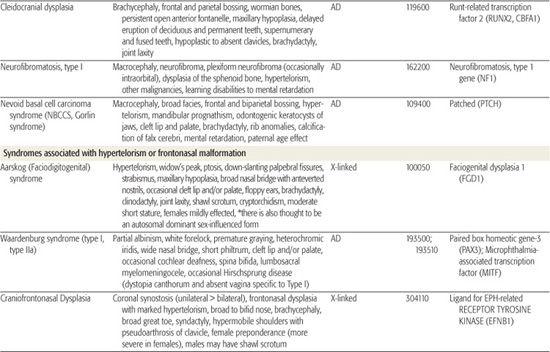

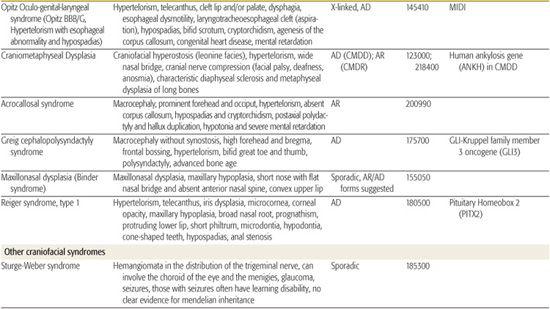

Table 177-1. Common Malformations and Syndromes Involving Craniofacial Structures

FIGURE 177-1. Hereditary cleft lip and palate. Variable expression of cleft lip and palate in two children born to different unaffected fathers. Their mother (far left) shows no manifestation of orofacial clefting.

Although the majority of children with CLP have this condition as an isolated malformation, there are over 462 associated syndromes associated with clefting.6,7 Relatively common syndromic forms of orofacial clefting include: Stickler syndrome, 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (also known as velocardiofacial syndrome), Van der Woude syndrome, and ectodermal dysplasia ectrodactyly and clefting (EEC) syndrome (Table 177.1). A greater percentage of syndromic forms are associated with cleft palate rather than cleft lip and palate. The number of syndromes associated with CLP underscores the importance of a careful physical exam and the need for multidisciplinary team management. Typically, clefts of the lip (primary palate) extend toward or into the floor of the nostril. Midline (median) clefts are commonly associated with frontonasal dysplasia, holoprosencephaly, or other disruptions in frontonasal development. For these reasons, infants with midline clefts of the lip require careful examination that should include CT or MRI imaging of the central nervous system.

Management

Management of children with CLP varies between centers of care, though the American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association (ACPA) has developed a set of practice guidelines for minimum standard of care for children with orofacial clefts.8 We briefly discuss some of the management recommendations below, and refer the reader to the ACPA Web site (http://www.acpa-cpf.org/) and “Critical Elements of Care for a Child with Cleft Lip and/or Palate” for additional detail.9

Airway The first issue to be addressed in an infant with an orofacial cleft is airway management. Although children with cleft palate (without cleft lip) are more prone to airway difficulties, children with CLP can also have upper-airway obstruction. Infants with Robin sequence are at highest risk of airway compromise. Robin Sequence is the association of micrognathia (small mandible) and glossoptosis (posteriorly placed tongue), with a cleft of the secondary palate. Although the pathogenesis of Robin sequence has not been proven, it is generally accepted that micrognathia leads to cleft palate about the sixth week of gestation because of the superior displacement of the tongue into the nasopharynx, preventing fusion of the palatal shelves. The combination of micrognathia and a palatal cleft often results in glossoptosis, and subsequent upper-airway obstruction. This phenomenon requires urgent care ranging from prone positioning to emergent tracheostomy. Some centers use other surgical and non-surgical means of treatment for more severe obstruction (eg nasopharyngeal intubation or neonatal mandible distraction). Craniofacial providers routinely use prone positioning as the first line of treatment to alleviate mild to moderate airway compromise associated with Robin malformation.10

Feeding Ensuring adequate caloric intake is the second most important issue in the management of children with CLP. Children with cleft palates cannot solely breast feed. This is because an intact palate is necessary to generate the negative pressure required for suckling. For this reason, a number of specialized feeding techniques (eg, squeeze bottles) have been devised11 (eFig. 177.1  ). Any child with nonsyndromic cleft palate should be expected to have normal weight gain. A general rule of thumb is that the neonate should take approximately 2.5 ounces/pound/day to have good growth (30 grams/day in the first 2 months, dropping to 15 grams/day by 6 months of age). Adequate weight gain is imperative in infants who will require surgical interventions in the first year of life. Infants with cleft palate may have minor swallowing difficulties and/or gastroesophageal reflux (particularly in infants with Robin sequence and syndromic forms of clefting, eg, 22q11.2 deletion syndrome). This should be taken into consideration during their management.

). Any child with nonsyndromic cleft palate should be expected to have normal weight gain. A general rule of thumb is that the neonate should take approximately 2.5 ounces/pound/day to have good growth (30 grams/day in the first 2 months, dropping to 15 grams/day by 6 months of age). Adequate weight gain is imperative in infants who will require surgical interventions in the first year of life. Infants with cleft palate may have minor swallowing difficulties and/or gastroesophageal reflux (particularly in infants with Robin sequence and syndromic forms of clefting, eg, 22q11.2 deletion syndrome). This should be taken into consideration during their management.

Surgery The timing and nature of surgical management for children with CLP differs among cleft centers. In general, closure of the lip occurs within the first 5 months of life and the palate is repaired by age 12 months. The timing of palatal closure by age 1 year is suggested to optimize speech and language development, but early palate closure (< 6 months) may impede normal midfacial development. Special attention needs to be given to the child with isolated cleft palate associated with respiratory difficulties (particularly in children with Robin sequence). Closure of the palate may exacerbate airway compromise in these patients. Thus, clinicians must individualize the treatment plan for timing of palatal closure for infants with a history of airway compromise. In addition to the need for surgical management of the cleft, children with cleft palate have an increased risk of persistent middle ear effusions (MEE) and chronic, recurrent otitis media (OM). Children with palatal clefts are predisposed to MEE and OM as a result of abnormal function of the distal eustachian tube. Because children with CLP are also predisposed to speech difficulties because of their clefts, it is imperative to optimize hearing. Most children with cleft palate require the placement of tympanostomy tubes in the first year of life. Additional surgeries that may be necessary in this population include bone grafting of the alveolar cleft(s), pharyngeal surgeries for improvement of speech, and midfacial advancement for children and teenagers with midfacial hypoplasia.

BRANCHIAL ARCH DERIVATIVE ANOMALIES

Several human malformation syndromes and sporadic conditions are associated with abnormalities in the development of the derivatives of the first and second branchial arches. These conditions share common symptoms and treatments and thus are discussed here together.

CRANIOFACIAL MICROSOMIA (HEMIFACIAL MICROSOMIA, OCULOAURICULOVERTEBRAL DYSPLASIA)

CRANIOFACIAL MICROSOMIA (HEMIFACIAL MICROSOMIA, OCULOAURICULOVERTEBRAL DYSPLASIA)

The association of external ear anomalies (microtia, anotia, canal atresia, and/or preauricular tags) with maxillary and mandibular hypoplasia is the second most common craniofacial malformation in humans, 1 in every 3000 to 5000 live births (eFig. 177.2  ). This condition, referred to as craniofacial microsomia (CFM) (also known as hemifacial microsomia, oculoauriculovertebral dysplasia, lateral face dysplasia, or first and second branchial arch syndrome), can present with a wide degree of severity. CFM can present as an isolated malformation of craniofacial structures or can represent a component of a multiple malformation complex (eg, Goldenhar syndrome, CHARGE, VATER). Some children with apparently isolated microtia may have other extracranial anomalies associated with CFM, and others may develop facial asymmetry over time.12,13 Therefore, we consider microtia to be a forme fruste of CFM. Because approximately 10% to 30% of cases of HFM are bilateral, most clinicians prefer the term craniofacial microsomia for this disorder.

). This condition, referred to as craniofacial microsomia (CFM) (also known as hemifacial microsomia, oculoauriculovertebral dysplasia, lateral face dysplasia, or first and second branchial arch syndrome), can present with a wide degree of severity. CFM can present as an isolated malformation of craniofacial structures or can represent a component of a multiple malformation complex (eg, Goldenhar syndrome, CHARGE, VATER). Some children with apparently isolated microtia may have other extracranial anomalies associated with CFM, and others may develop facial asymmetry over time.12,13 Therefore, we consider microtia to be a forme fruste of CFM. Because approximately 10% to 30% of cases of HFM are bilateral, most clinicians prefer the term craniofacial microsomia for this disorder.

Inheritance of Craniofacial Microsomia

Although the etiology of CFM is unknown, there is evidence for genetic contribution. Investigators suggest that CFM is secondary to abnormal development of the first and second branchial arches at sixth week of pregnancy. Although the recurrence risk for most parents that have one child with CFM is relatively low (2–3%), in some families there is an autosomal pattern of inheritance and the recurrence risk is 50%.14 Results from recent epidemiologic studies also support an association between CFM and vasoactive and environmental exposures in utero.15

Management

Children with CFM require multidisciplinary surgical and medical care. As with neonates with CLP, the most critical issues to address in newborns with CFM involve airway and feeding difficulties. Patients with severe CFM can have airway obstruction because of mandibular and maxillary hypoplasia. The management of upper-airway obstruction may require prone or side lying positioning, early mandibular surgery, or tracheostomy. Severe mandibular and/or maxillary deficiency can negatively impact oral feeding in the first months of life. Temporary nasogastric, and less commonly gastrostomy, feeding may be necessary.

In addition to the craniofacial manifestations, there is a relatively high incidence of associated renal and vertebral anomalies. Infants with CFM should have a renal ultrasound to rule out renal malformations (10–15% estimated to have some renal or collecting system anomaly). In addition, between 25% to 30% of children with “isolated” CFM have vertebral anomalies. Structural malformations of the spine rarely have functional significance until later childhood, and spine films can be delayed until age three to allow more complete ossification and improve the quality of the study. Children age 5 and older with CFM who participate in activities that put the cervical spine in jeopardy should have full cervical spine radiographs (including flexion/extension views to rule out cervical instability) and careful exam to assess for scoliosis. Providers should have a low threshold for obtaining thoracic/lumbar radiographs for children with signs of spinal curvature. All children with CFM should have an audiologic evaluation (brainstem auditory evoked response, or other accepted means). Even in apparently unilateral cases there is a high likelihood of bilateral hearing loss. This is often a conductive hearing loss (the result of malformations of the middle ear ossicles) but a mixed sensory and conductive deficit may be present (particularly in syndromic forms, see Table 177.1).

The most important health care issues for older children with CFM are related to (1) hearing, (2) functional reconstruction of the maxilla and mandible, (3) orthodontic issues, and (4) external ear reconstruction.16-18 Each child has unique needs and requires tailored care by a qualified multidisciplinary team.

Goldenhar syndrome is considered to represent the severe end of the CFM clinical spectrum, and includes epibulbar lipodermoids (fibro-fatty masses on the globe of the eye, usually lateral and/or inferior), vertebral defects (fusions and/or hemivertebrae of the cervical-lumbar vertebrae), cardiac malformations (from VSD to out-flow tract malformations), and structural kidney malformations.

BOR SYNDROME

BOR SYNDROME

Branchio-oto-renal dysplasia (BOR syndrome) is an autosomal-dominant condition that shares many features with CFM. Children with BOR rarely have severe maxillary or mandibular deficiency. The syndrome is characterized by the presence of external ear malformations (“lop” ear), preauricular pits and occasional tags, branchial cleft fistulae of the neck (sometimes extending into the pharynx), mixed sensory and conductive hearing loss associated with cochlear and ossicular chain malformations, renal dysplasia or aplasia, and occasional pulmonary hypoplasia. Recently, a mutation of EYA1 has been identified as the cause of some cases of BOR syndrome (Table 177.1).

TREACHER COLLINS SYNDROME (MANDIBULOFACIAL DYSOSTOSIS TYPE I)

TREACHER COLLINS SYNDROME (MANDIBULOFACIAL DYSOSTOSIS TYPE I)

Treacher Collins syndrome is an autosomal-dominant craniofacial malformation syndrome that shares some phenotypic features with CFM. It is caused by a mutation in the treacle gene (TCOF1) and can have significant phenotypic variability between or within affected families. The disorder is characterized by mandibular and maxillary hypoplasia; zygomatic arch clefts; and variable microtia, anotia, and atresia. Facial features are significant for downward-sloping palpebral fissures (because of lateral orbital clefts), and colobomata of the lower eyelids. Cleft palate occurs in a minority of patients (Fig. 177-2). The hypoplastic mandible usually has a characteristic exaggeration of the antegonial notch (eFig. 177.3  ). Cognition is usually normal and other malformations (eg, cardiac) are rare. Treacher Collins syndrome is usually associated with conductive hearing loss. The clinical management for children with Treacher Collins syndrome is very similar to that of children with bilateral CFM (respiratory, feeding, mandibular/maxillary surgery, external ear reconstruction). Two more rare forms of recessive mandibulofacial dysostosis include Nager and Miller syndrome (see Table 177.1).

). Cognition is usually normal and other malformations (eg, cardiac) are rare. Treacher Collins syndrome is usually associated with conductive hearing loss. The clinical management for children with Treacher Collins syndrome is very similar to that of children with bilateral CFM (respiratory, feeding, mandibular/maxillary surgery, external ear reconstruction). Two more rare forms of recessive mandibulofacial dysostosis include Nager and Miller syndrome (see Table 177.1).

ABNORMAL HEAD SHAPE

Abnormalities of head shape are common in infancy. In this section we will describe and distinguish between the most common forms of primary and acquired head shape abnormalities.

POSITIONAL PLAGIOCEPHALY

POSITIONAL PLAGIOCEPHALY

Positional plagiocephaly is a postnatal deformation of the skull because of the positional preference of the infant. Persistent pressure on one aspect of the skull leads most commonly to flattening of the occipitoparietal area. This flattening can be of sufficient severity that it leads to secondary changes, including ipsilateral frontal prominence and anterior displacement of the ipsilateral ear. Infants with plagiocephaly frequently also have torticollis. The natural history of positional plagiocephaly is as follows: (1) normal head contour at birth (unless in utero deformation is present), (2) occipital flattening noted by age 1 to 2 months (infant usually demonstrating a sleep position preference and/or torticollis at this time), (3) increasing severity until 4 to 5 months, (4) improvement in head contour between 4 and 7 months, and (5) static head deformation after 7 months. The final head shape can be improved by reducing supine positioning while child is awake. It is also important to initiate early therapy by a qualified occupational or physical therapist to increase the neck range of motion for infants with torticollis. Ophthalmologic and cervical spine anomalies should be ruled out, when indicated, based on history and exam. The incidence of this postnatal deformation has increased with the supine sleep position recommended to reduce the incidence of SIDS.19 The most dramatic aspect of the deformation is the occipital skull flattening, often leading to the misdiagnosis of unilateral lambdoid synostosis. Positional plagiocephaly can be distinguished from lambdoid synostosis by physical exam (Table 177.2; eFig. 177.4) and skull radiography (sclerosis of lambdoid suture can be seen on plain films or preferable CT scan).20

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree