Core Competencies

Theodore C. Sectish

In 1910, Flexner issued to the Carnegie Foundation a report on the state of medical education1 that transformed the training of physicians in the United States. Residency training, modeled on the Flexner report, was an apprenticeship in hospitals. Residency training evolved to include structured curricula and specified clinical experiences designed to develop knowledge, skills, and behaviors of physicians within each specialty and general discipline. Over time, the context of training programs changed rapidly as teaching hospitals accomplished their missions of patient care, research, and education while attempting to stay financially solvent in an increasingly competitive medical marketplace. The increasing complexity of patient care and that of the medical care system imposed additional challenges to the environment in which residents were trained.

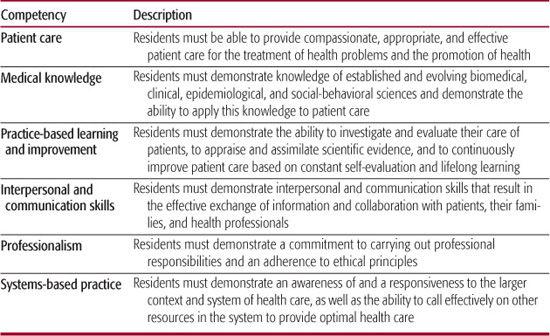

The evolution of individual training programs and the graduate medical education enterprise in general did not keep pace with these changes.2 During this same time period, despite enormous advances in medical science and achievements in altering the natural history of disease, the medical profession failed to stay focused on the quality of care, as reported by the Institute of Medicine in 2000.3 As a result, public trust in the medical profession has eroded in the United States. One response within organized medicine was to examine the training of physicians and focus on the outcomes of training rather than merely on the structure and process of training, a shift that represents a huge transformation in graduate medical education to competency-based training. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) incorporated the following six competencies into the training requirements for all accredited residency training programs: patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice.4 These competencies have been embraced throughout organized medicine. The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) adopted the competencies for maintenance of certification for specialists, and the Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) suggests that medical staffs incorporate the assessment of competence into credentialing practices.5,6 The assessment of competence along the continuum of professional development is directly linked to the intended outcome of improving quality of care. Although this chapter examines the competencies in pediatrics from the perspective of residency training, measurement of achievement of these same competencies for certification will eventually be applied throughout the profession of pediatrics.

COMPETENCE: DEFINITION AND STAGES

Epstein and Hundert define professional competence as “the habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of the individual and community being served.”7 The attainment of competence occurs gradually over time in a developmental progression. Dreyfus and Dreyfus observed this progression in other realms, but their model may be applied to the development of professional competence in medicine, from medical school through residency and into later professional life.8 The stages they describe are novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient, expert, and master.

A simplified description of the stages is useful in understanding the application to medicine. Progression from novice to advanced beginner occurs in medical school, starting with the understanding, memorization, and application of medical knowledge. Novices learn clinical rules in the lecture hall and in the context of patient care. Aspects of doctoring include knowing facts, learning skills, and developing reasoning techniques. As medical students progress toward the advanced beginner stage, their experiences in clinical medicine coupled with basic knowledge of medical science allow them to integrate their knowledge and develop a more intricate understanding of context and common situations. In the process, they begin to employ cognitive shortcuts to approach ambiguous clinical scenarios. In residency training, the intense exposure to patients and a broad array of diseases facilitates a deeper level of understanding and new approaches to clinical problem solving. The goal of graduate medical education is for residents to attain the competent stage in which physicians plan multiple approaches to solve individual clinical problems in an effort to reduce ambiguity and uncertainty. After residency, proficient physicians develop routines that make their medical practices efficient. As physicians become expert in their practices, they navigate swiftly through uncertainty, often by relying on pattern recognition and by identifying key clues to solve clinical problems. Not all physicians achieve the master stage of competence in which their level of expertise is widely recognized within a field of medicine. Medicine is more complex in its day-to-day practice than this model would imply. Even experts who use pattern recognition and key clues to make inductive leaps must rely on skills acquired at earlier developmental stages when faced with uncertainty and will rely on deductive reasoning at times to solve clinical problems.

COMMON PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS

The ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Pediatrics incorporate the general competencies that are required for all residency training programs (see Table 6-1).9 When the competencies were first introduced in graduate medical education, program directors felt comfortable that their programs facilitated attainment of competence in many of the core competencies. Two competencies, practice-based learning and improvement and systems-based practice, required attention in most pediatric training programs. Elements of practice-based learning and improvement include developing the skills of self-assessment and lifelong learning, understanding quality improvement, utilizing information technology and incorporating evidence-based medicine into clinical practice, and participating in educational activities for patients and colleagues. Competence in systems-based practice includes developing an understanding of the variety of health care delivery systems, coordinating clinical care in complex patients, advocating for patients navigating the health care system, and identifying and addressing medical errors. These competencies relate to the needs of physicians who must update their knowledge to remain current in practice and the needs of the health care system to have physicians intimately involved in quality improvement.

Table 6-1. Core Competencies Statements

IMPLEMENTING THE COMPETENCIES INTO RESIDENCY PROGRAMS

In this era of competency-based graduate medical education, residency programs incorporate the competencies into the curriculum and establish methods of assessment to measure the attainment of competence in each area. In the past, training requirements were structure-and-process–based: Residents experienced a series of structured rotations with specified curricular goals and objectives over a 1-month period of time in specific curricular areas. For example, every pediatric resident must have 5 to 6 months of intensive-care training time with 3 to 4 months of neonatal intensive care and 2 months of pediatric critical care. In the structure-and-process approach, completion of this training requirement was attained by the resident successfully completing the requisite time on block rotations in neonatal and pediatric critical care units. Assessment methods used to evaluate successful completion of rotations were subjective, most often as global assessments of performance.

In a competency-based training model, goals and objectives of curricular components must be competency based. The ACGME Program Requirements further defines the competencies for their application to pediatrics residency by specifying elements under each general competency. eTable 6.1  illustrates examples of elements under each competency domain and examples of assessment methods. Once competency-based goals and objectives are specified, the next step is to determine educational strategies to meet the curricular goals and objectives. At present, most residency programs continue to design the curriculum around time-based experiences rather than attainment of competence. The major difference in competency-based training is in the approach to evaluation. In the companion document that accompanies the ACGME Program Requirements, methods of assessment are suggested for each competency to measure the attainment of competence within residency programs (see eTable 6.1

illustrates examples of elements under each competency domain and examples of assessment methods. Once competency-based goals and objectives are specified, the next step is to determine educational strategies to meet the curricular goals and objectives. At present, most residency programs continue to design the curriculum around time-based experiences rather than attainment of competence. The major difference in competency-based training is in the approach to evaluation. In the companion document that accompanies the ACGME Program Requirements, methods of assessment are suggested for each competency to measure the attainment of competence within residency programs (see eTable 6.1  ).

).

Assessment of competence requires methods of assessment beyond global evaluations. An array of assessment methods are suggested by the ACGME:

1. Direct observation of residents in interactions with patients, presenting on rounds, or conducting a teaching session.

2. Multisource feedback and evaluation from patients and families, colleagues, and other professional staff.

3. Self-assessment and reflective narratives.

4. Simulation training experiences, such as crisis resource management or delivering bad news to patients and families.

5. Observed structured clinical examinations with or without standardized patients.

6. Record reviews.

7. Knowledge tests.

8. Case logs.

The Association of Pediatric Program Directors (APPD) launched a project to share assessment tools called the Share Warehouse for members of APPD.10

Assembling multiple methods of assessment from a variety of clinical experiences and from multiple sources in addition to faculty provides evidence that an individual attains the overarching goal of becoming competent. When coupled with reflection and self-assessment, these formative and summative evaluations form the basis of a learning portfolio. The ACGME maintains an Internet-based learning portfolio in an effort to develop portfolio components for individual specialties and to test the electronic platform.11 It is conceivable that this Internet-based portfolio approach may be applied beyond residency and serve as a basis for continuous professional development. Promoting reflection in residency training may facilitate development of lifelong learning skills. Ultimately, these skills lead to reflective practice in which the individual makes an ongoing effort to update patterns of practice and improve patient care.

SUMMARY

The transition to competency-based training has been described as a journey to authenticity as doctors and as a profession.12 The core competencies have changed the conceptual model of residency programs by placing the outcome of training as the end goal. Assessment of competencies brings an enhanced focus to fostering the professional development of individual residents along the competence continuum. Authentic assessment has the potential to measure what is most relevant to the practice of medicine and those aspects of doctoring that matter most to patients and families. As we look beyond residency training to the future of maintenance of certification for all ABMS specialty fields, physicians will soon complete a 4-part process: (1) holding a valid, unrestricted license; (2) participating in lifelong learning and self-assessment; (3) demonstrating cognitive expertise within the specialty field; and (4) systematically analyzing practice with the intent of improvement. Thus, the focus on these core competencies in residency training programs has laid the foundation for the continuous professional development of physicians. Despite the ever-increasing complexity of the practice of medicine, the focus on the competencies and the attainment of competence are now core features of physician training and will remain central to continuous professional development and improvement in the quality of patient care.

REFERENCES

See references on DVD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree