Constipation and Fecal Incontinence

Manu R. Sood

Constipation is a common problem in children and is often associated with maladaptive behavior triggered by a painful or otherwise unpleasant defecation. There is no universally accepted definition of constipation, although the term is generally describes infrequent or painful bowel movement due to stool that is too large or hard to pass.1,2 The Rome Committee, consisting of a group of pediatric gastroenterologist from Europe and North America, defined constipation as 2 or more of the following symptoms in a child with a developmental age of at least 4 years: 2 or fewer defecations in the toilet per week, at least 1 episode of fecal incontinence per week, history of retentive posturing or excessive volitional stool retention, history of painful or hard bowel movements, presence of a large fecal mass in the rectum, and history of large-diameter stools that may obstruct the toilet.3,4

EPIDEMIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The incidence of constipation in 5 to 21 year olds is estimated to be 3.9 per 1000 person-years. The prevalence of constipation in children ranges from 0.7% to 29.6% (median 8.9%).5,6 About 3% of children experience constipation in the first year of life and about 10% in the second year of life.7 Constipation accounts for almost 3% of general pediatric outpatient clinic visits and 10% to 25% of visits to a pediatric gastroenterology clinic. Most cases of functional constipation present between ages 2 and 4 years. The incidence of constipation in children younger than 13 years is similar between genders, but in older children, girls seek medical help more often than boys. In school-aged children, fecal soiling is 3 times more common in boys than in girls. The incidence increases when a parent, sibling, or twin has constipation. Monozygotic twins are 4 times more likely than dizygotic twins to have constipation.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

A normal pattern of defecation requires the removal of water from the liquid chyme that enters the cecum and propulsion of soft, formed colonic contents through the colon to the rectum, which stores stool until defecation. Sensation of the need to pass stool by rectal smooth muscle contraction and reflexive partial inhibition of the internal anal sphincter allows stool to impinge on the sensory area of the mucosa of the upper anal canal. To achieve continence, the child must be able to perceive this urge to defecate, and then, if in the appropriate setting, the child must plan to find a lavatory depending on the urgency. This is not an innate ability but requires learning in a supportive environment. If the child has learned that stooling is painful, or if appropriate access to a socially acceptable location for passing stool is unavailable, the child withholds the stool by external anal sphincter and pelvic floor contraction. The expulsion of the stool requires an increase in intra-abdominal pressure by bearing down.

Constipation results from either slow transit of the stool through the colon due to an underlying neuromuscular disorder or from outlet obstruction due to mechanical obstruction (tumors, stricture), abnormal defecation (dysnergia), or stool-withholding behavior. Whatever the cause of stool retention, fluid absorption desiccates the stool, resulting in increased hardness. Causes of incontinence other than function fecal retention are discussed further in this chapter.

CLINICAL FEATURES AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

CLINICAL FEATURES AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

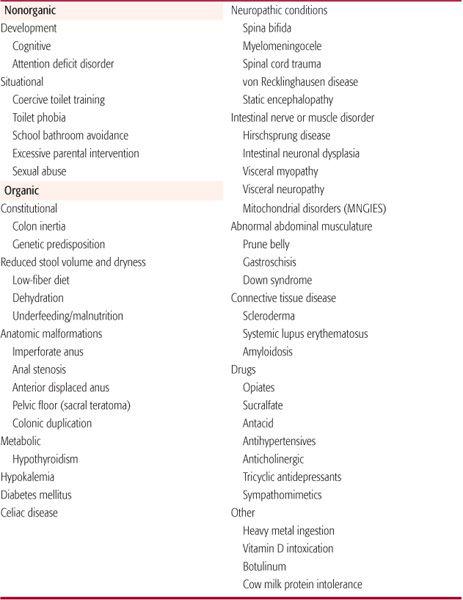

Constipation is a symptom, not a disease, and can be associated with a number of disorders (Table 386-1). The majority of children with chronic constipation have no clearly identifiable disorder, and their condition is therefore labeled functional or idiopathic constipation. Passage of a large-diameter or hard stool is painful. Repeated painful experiences can scare the child and prompt stool-avoidance behavior. Almost 75% of children with functional constipation have experienced painful bowel movements, and 97% have a fear of defecation. Therefore, prompt treatment of constipation is important to prevent further difficulties.8,9

Some children can withhold stool for up to 2 to 3 weeks. They adopt various “stool retentive” postures in an attempt to avoid defecation, such as standing in the corner on tip toes with stiffening of the body to contract the gluteal muscle while screaming or breath holding in response to the sensation of an urge to defecate. This behavior (often called the “potty dance”) is often confusing to caretakers who interpret it as discomfort due to constipation rather than as stool-withholding behavior. As stool accumulates in the rectum, mood deteriorates, appetite decreases, and the child experiences abdominal pain and distension.

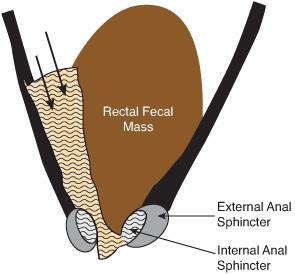

The child ultimately develops overflow incontinence in which the liquid stool seeps around the rectal fecal mass and the child passes small amounts of soft stool several times a day (Fig. 386-1). Sometimes this can be confused with diarrhea, but a good clinical history distinguishes between the two. The loss of control over defecation confuses the child and often angers the parents. Overflow incontinence should be distinguished from fecal incontinence secondary to fecal urgency seen in patients with irritable bowel syndrome, neurologic disorders, and spinal disorders. Children with behavioral disorders and sexual abuse can also present with fecal incontinence. Urinary tract infection occurs in 5% to 10% of chronically constipated children, probably secondary to partial urethral obstruction or ascending infection from chronically soiled underwear.

In infants, constipation is somewhat more likely to be due to an underlying organic disorder such as an anatomic disorders (anterior ec-topic anus, rhabdomyosarcoma, stricture) or Hirschsprung disease, but in most cases, constipation is functional. It often results from dietary issues. Hard stool is more common in formula-fed infants than in breast-fed infants because of the higher protein-to-carbohydrate ratio and a lack of oligosaccharides in formula. Therefore, a change from breast milk to formula is associated with firm and less frequent bowel movements. Cow milk protein has also been implicated in chronic intractable constipation in infants and children. Breast-fed infants often pass stools infrequently (up to every 5 days), which may be normal if the stool is soft and passage is not painful.

In toddlers, conflict can arise out of overzealous or inappropriate toilet-training practices. The parents may have unrealistic expectations that can be influenced by socioeconomic factors. Working single parents or families in which both parents are working may be under pressure to toilet train their child before the child is eligible for preschool placement. Because of the need to get the child toilet trained, parents may seek medical help for toilet training. School-aged children may prefer to postpone defecation until they reach home because the school toilets are unhygienic. Repeated avoidance of bowel movements at school can lead to rectal fecal mass, which is painful to pass and may trigger fecal retentive behavior.

Table 386-1. Causes of Constipation in Children

It is important to differentiate fecal soiling associated with functional fecal retention from nonretentive incontinence. Children with this condition present with a history of passage of part or the entire stool in the underpants. The incontinence is sporadic rather than the continuous seepage seen in functional fecal retention. There is no history of passage of hard or large-diameter stool. In most cases, fecal incontinence is one of many difficult behaviors exhibited by the child. An ongoing struggle with the parents over many aspects of daily living is not unusual. Fecal incontinence is a behavioral manifestation of emotional disturbance and requires psychological evaluation and treatment. Laxative therapy frequently worsens the problem.

Spinal cord injury or dysraphism may results in slow-transit constipation and external anal sphincter and levator ani muscle dysfunction. In addition, the motor and sensory function of the rectum may be affected. Fecal incontinence, with or without constipation, is present in 11% to 30% of patients with myelomeningocele.10 Biofeedback training has been helpful in patients with preserved sensorimotor function in the perianal region and who are cooperative. High-fiber diet and daily digital rectal stimulation, suppositories, or enemas will allow acceptable control of fecal incontinence. Administration of antegrade colonic enemas through an appendectomy, a cecostomy, or a sigmoid colon button is beneficial in selected patients.11

Constipation is also common in children with neurodevelopmental disorders in whom abnormal skeletal muscle tone can cause poor defecatory effort, and enteric neuromusculature abnormalities may also cause slow-transit constipation. In addition, medications frequently administered to these children and diets low in fiber contribute to problems of constipation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree