Description

Size (cm)a

Incidence

Small

<1.5

Roughly 1:100

Medium

1.5–19.9

Roughly 1:1,000

Large

≥20

Roughly 1:20,000

Giant

>40–50

Roughly 1:500,000

Besides CMN diameter Krengel et al. [12] proposed a new classification for determining risks of adverse events that includes the following criteria: satellite nevus count, anatomic localization, color heterogeneity, surface, rugosity, hypertrichosis, and dermal or subcutaneous nodules (Table 27.2). Future development of a molecular genetic-based classification may greatly benefit from correlation with a standardized morphologic classification of CMN.

Table 27.2

Proposed classification of CMN by Krengel et al.

CMN parameter | Terminology | Definition |

|---|---|---|

CMN projected adult size | Small | <1.5 cm |

Medium | ||

M1 | 1.5–10 cm | |

M2 | 10–20 cm | |

Large | ||

L1 | >20–30 cm | |

L2 | >30–40 cm | |

Giant | ||

G1 | >40–60 cm | |

G2 | >60 cm | |

Multiple medium size | ≥3 medium CMN without a single predominant CMN | |

CMN localizationa | ||

Head | Face, scalp | |

Trunk | Neck, shoulder, upper back, middle back, lower back, breast/check, abdomen, flank, gluteal region, genital region | |

Extremities | Upper arm, forearm, hand, thigh, lower leg, foot | |

No. of satellite nevib | S0 | No satellites |

S1 | <20 satellites | |

S2 | 20–50 satellites | |

S3 | >50 satellites | |

Additional morphologic characteristics | C0, C1, C2 | None, moderate, marked color heterogeneity |

R0, R1, R2 | None, moderate, marked surface rugosity | |

N0, N1, N2 | None, scattered, extensive dermal or subcutaneous nodules | |

H0, H1, H2 | None, notable, marked hairiness | |

Epidemiology/Demographics

Prevalence of CMN is 1–2.4 % of newborns

Race: African and Japanese decent higher incidence than Hispanics or whites

Incidence of giant CMN: 1:500,000

CMN are common neoplasm of the newborn skin; the estimated prevalence of CMN varies widely depending on the study, ranging from 0.5 to 31.7 %. GCMN are uncommon among them [3, 5, 15–18]. Most of them are 3–4 cm in diameter; the incidence of lesions greater than 10 cm in diameter has been calculated as only 1 in 20,000 newborn. Larger ones are less common. GCMN have an estimated incidence of 1 in 500,000 live births (Table 27.1) [4, 9, 14]. Kanada et al. [19] in a prospective study enrolled 594 infants in San Diego, California, USA, seen in the first 48 h of life, to provide data based on ethnicity, prematurity, and body site for vascular, pigmented, and other common cutaneous findings and compared their results with previous international prospective studies. In their study CMN was defined as flat or raised, tan brown or black, usually sharp regular symmetrical borders. CMN were found in 2.4 % of the studied newborns, among them 2.6 % were Caucasian, 17.9 % were African-American, 1.9 % Asian, none lesions were found among Hispanic patients, and 1.3 among other races (Table 27.3). Comparing their study with the incidence of CMN in previous international studies is shown in Table 27.4. Using the sliding scale metric defined by Marghoob et al. [10] for infants, all CMN reported in Kanada et al. [19] study qualified as small or medium. No neonate has more than one CMN, and none had large or giant CMN. People of African and Japanese decent appear to have higher incidences of CMN than Hispanics or whites [15–18, 20–28].

Cutaneous lesion | Total (%) | Caucasian (%) | Hispanic (%) | African-American (%) | Asian (%) | Other (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

CMN | 2.4 | 2.6 | 0 | 17.9 | 1.9 | 1.3 |

Small | 1.3 | 1.5 | 0 | 10.7 | 0 | 1.3 |

Medium | 1 | 1.1 | 0 | 7.1 | 1.9 | 0 |

Large/giant | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Kanada et al. | Alper and Holmes | Jacobs and Walton | Shih et al. | Magaña-García and Gonzales-Campos | Kahana et al. | Tsai and Tsai | Karvonen et al. | Nanda et al. | Hidano et al. | Dickson and Yue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Country | US | USA | USA | Taiwan | Mexico | Israel | China | Finland | India | Japan | Australia |

Year publication | 2011 | 1983 | 1976 | 2007 | 1997 | 1995 | 1993 | 1992 | 1989 | 1986 | 1979 |

Number of patients | 594 | 4,641 | 1,058 | 500 | 1,000 | 1,672 | 3,345 | 4,346 | 900 | 5,387 | 100 |

CMN (%) | 2.4 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 2.5 | 0.35 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 0.44 | 2.7 | 1.0 |

Clinical Presentation

Localization: more frequent on the trunk and extremities, but head and neck lesions more disfiguring.

Classical presentation: brown-black elevated plaque studded with small nodules and coarse hair, with a regular smooth and well demarcated border. Satellite melanocytic nevi common among GCMN.

Lesions usually increase in size, color, and more hair, but pigmentary regression can occur.

Proliferative nodules may appear within the nevus, which usually represent benign neurotization of the nevus

The classical presentation of CMN is a brown-black elevated plaque studded with small nodules and coarse hair, with a regular smooth and well demarcated border [5, 29, 30]. Compared to benign acquired nevi, CMN are larger in size and display a mottled heterogeneous morphology (Fig. 27.1). They typically occur on trunk (38 %) and extremities (38 %). Head and neck lesions are infrequent (14 %) but quite disfiguring [4–7, 31]. The clinical appearance may change with age. In neonates, they may be lighter in color and relatively hairless, with flat poorly marginated border, or raised darkly pigmented, well marginated lesion with an irregular rugged surface, associated with dense, coarse, darkly pigmented hairs. In childhood, there is a progressive darkening of lightly colored lesions, and may acquire long, coarse, darkly pigmented terminal hairs in 75 % of them. Less commonly lanugo hairs overlie the lesion (Figs. 27.2 and 27.3) [4, 5, 30].

Fig. 27.1

Large CMN: Note different colors and surface changes within the nevus. Several “proliferative nodules” are present

Fig. 27.2

GCMN: Note heterogeneous colors and morphology. Coarse terminal darker pigmented hair is noted in some areas of the nevus

Fig. 27.3

Giant CMN on the trunk and proximal inferior limbs; Note different colors and structures. “Proliferative nodules” are also observed. Note satellite lesions

The color is generally uniform, but sometimes they exhibit considerably pigment color variation. Nearly all CMN have brown as their primary color, although it may be admixed with black, blue, and gray (Fig. 27.4). With the passage of time CMN may get darker, lighter, loose pigmentation, become more heterogeneous, or, rarely, regress (Fig. 27.5) [4, 11, 31].

Fig. 27.4

Large CMN. Note more homogeneous dark brown color and vellus, lanugo hairs cover most of the nevus surface

Fig. 27.5

GCMN on the trunk. Note uniform color and lanugo-like hairs

The surface of CMN may be smooth, but frequently as the patient ages, a papular, pebbly, verrucous, or even cerebriform appearance became evident. Proliferative nodules may appear within the nevus, which usually represent benign neurotization of the nevus [4–6, 11, 32].

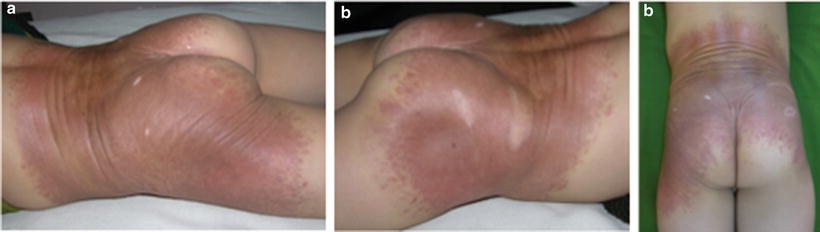

GCMN are often associated with satellite melanocytic nevi; these are smaller CMN that are present at birth or arise months to years later (Fig. 27.6) [11, 32].

Fig. 27.6

Giant congenital bathing suit type nevus. Note smaller “satellite” lesions

CMN have a dynamic course and may change over time. They can increase in size during childhood, become darker in color, become hairy, or show pigmentary regression. Spontaneous involution of CMN is rare and is usually associated with hypopigmented halo phenomenon or vitiligo (Fig. 27.7) [33–35]. Cusack et al. [36] described a case of complete regression over a 4-month period with the halo phenomenon of a medium-sized CMN. A control biopsy showed prominent lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis and aggregates of lymphocytes adjacent to the nevus in the deeper dermis, supporting an autoimmune mediated phenomenon which involves T-cell immunity and the presence of IgM autoantibodies [37, 38].

Fig. 27.7

“Halo nevus” phenomenon may be observed in congenital and acquired nevi. The patient has vitiligo as well

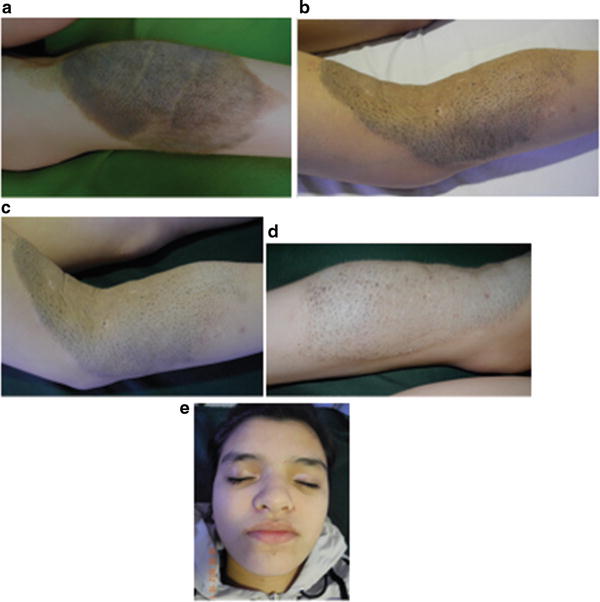

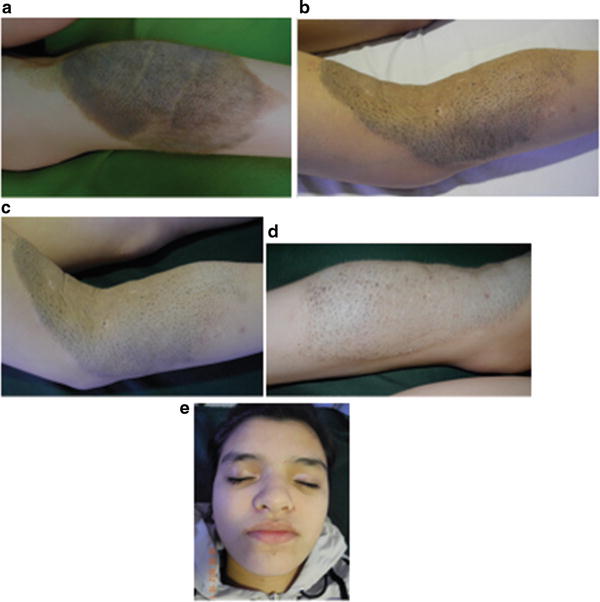

Spontaneous regression without the halo phenomenon has also been described. Despite the clinical involution, pigment regression may be accompanied by histological persistence of nevus cells. Halo nevi usually occur during childhood or adolescence [3]. The depigmentation may occur within the lesion, around it or at a distant site (Fig. 27.8a–d) [37]. Spontaneous regression of a CMN starts with loss of terminal hairs and epidermal pigments resulting in bluish color of the plaque, which is followed by flattening and loss of dermal pigments resulting in vitiligo-like leukoderma. Dermal nevus cells, however, do not disappear; they just loose the ability to produce melanin pigments. The process of regression is associated with lymphocytic infiltration [37].

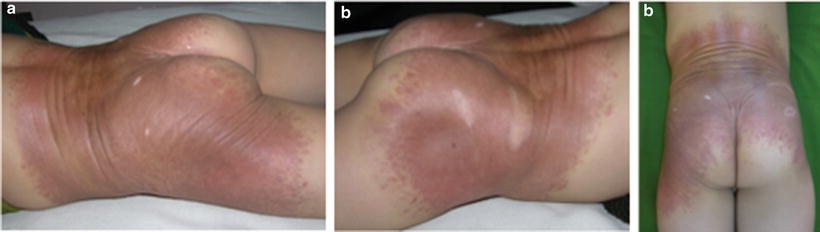

Fig. 27.8

(a–d) Note regression of a large congenital melanocytic nevus. Loss of color of the nevus and surface thickness. Note loss of hair color and hairiness within the nevus. Vitiligo like areas are noted within the nevus. (e) The patient developed vitiligo on distant sites. Note color loss on both superior eyelids

Regression of CMN without the halo phenomenon has been described [33]. Vilarrasa et al. [39] reported the clinical cases of medium-to-large CMN that clinically disappeared without the halo phenomenon. In both cases, skin biopsies showed that a high proportion of amelanotic nevus cells were still present in the dermis and even extended to the subcutaneous fat and pilosebaceous unit, indicating a decrease in melanin production by dermal nevus cells, rather than a reduction in their number [11, 33, 40–43].

Desmoplastic hairless hypopigmented nevus (DHHN) was first described by Ruiz-Maldonado et al. [44] as a hard, ligneous, progressively hypopigmented and alopecic GCMN. In such cases they noted progression of the induration in three cases and regression in the other patient. Histopathological (HP) appearance is characterized by intense dermal fibrosis and nevus cell depletion without evidence of malignant transformation. Boente and Asial [45] described a case of DHHN in which a well demarcated tumor appeared during the follow-up. Histology of such tumor showed nevus cells of normal morphology between thick collagen bundles; immunostaining revealed that such nevus cells have S100+, Vim+, HMB45 staining. An immune response against the melanocyte of the nevus may explain this type of evolution. Persistence of nevus cells was described in a case of involution of a neonatal eroded giant CMN with desmoplastic reaction (Fig. 27.9a–c) [46].

Fig. 27.9

(a–c) DHHN: Note hairless GCMN with peculiar ligneous appearance and regression signs

CMN rarely affect the scalp in the form of a giant cerebriform nevus; the skin is thrown into folds resembling the undulation of the cortical surface of the brain [30].

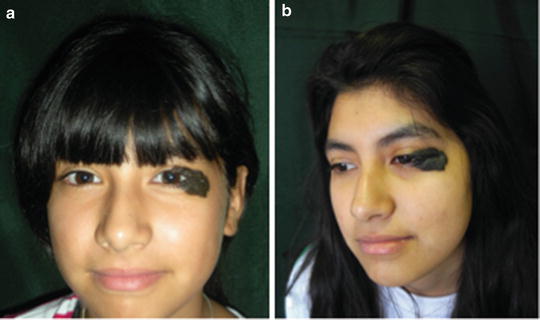

Kissing nevus or divided nevus of the eyelid occurs in adjacent parts of the upper and lower eyelids. When the eyelid is closed it appears as a single lesion. This implies that CMN develop between the 9th and 20th week of gestation, when the eyelids are fused (Fig. 27.10) [5, 47].