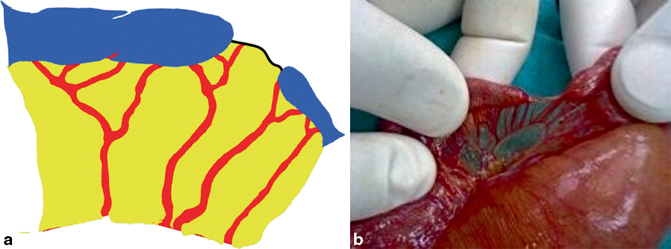

Fig. 23.1

Operative (a) and diagrammatic (b) representation of type I intestinal atresia. There is continuity of bowel, no defect in the mesentery and an intraluminal diaphragm

In type I atresias, there is an intraluminal diaphragm (membrane).

As in duodenal webs, a windsock effect may be seen secondary to an increase in intraluminal pressure in the proximal dilated bowel causing a prolapse of the web into the distal part of the bowel.

There is no defect in the mesentery.

The bowel length is normal.

Type II (Fig. 23.2):

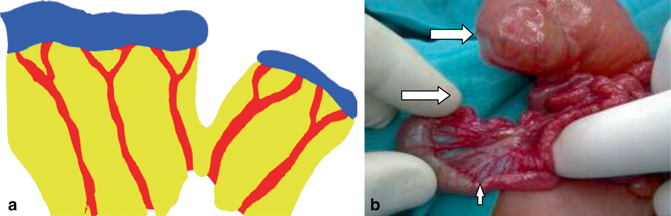

Fig. 23.2

Diagrammatic (a) and operative (b) representation of type II intestinal atresia. There is a fibrous cord connecting the two intestinal segments with an intact mesentery. This is in a patient with multiple intestinal atresias. Note the dilated segment of bowel proximal to another atresia

In type II atresia, the affected segments of intestines are separated from each other and the dilated proximal portion has a bulbous blind end connected by a fibrous cord to the blind end of the distal collapsed bowel.

The mesentery is intact.

The bowel length is usually normal.

Type IIIa (Fig. 23.3):

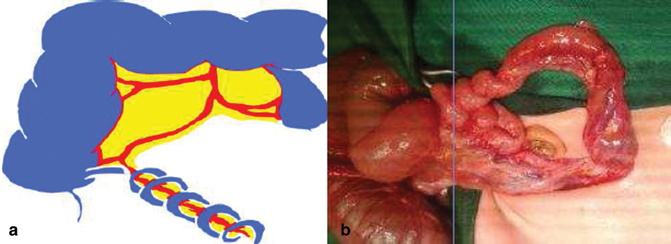

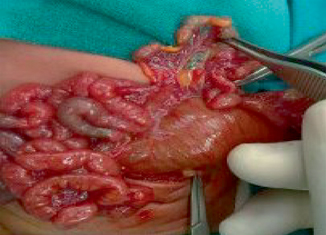

Fig. 23.3

Diagrammatic (a) and operative (b) representation of type IIIa atresia. Note the defect in the mesentery and the two atretic ends separated with no fibrous cord between them. Note also the distal type I atresia (thin arrow)

In type IIIa atresia, the affected segments of intestines are separated from each other without a connecting fibrous cord and the dilated proximal portion has a bulbous blind end which is separated from the blind end of the distal collapsed bowel.

A V-shaped mesenteric defect is present.

The intervening bowel has undergone intrauterine resorption, and, as a result, the bowel is variably shortened.

Fig. 23.4

Diagrammatic (a) and operative (b) representation of type IIIb atresia (apple peel deformity). There is a single feeding vessel around which the intestines are twisted

Fig. 23.5

Intraoperative photograph showing apple peel deformity. Note the single feeding artery

Type IIIb atresia is also known as a Christmas tree or apple peel deformity because of the appearance of the bowel as it wraps around a single feeding vessel.

There is a large defect in the mesentery.

The bowel length is significantly shortened.

The distal small bowel receives its blood supply from a single ileocolic or right colic artery.

Many patients with this type of intestinal atresia have low birth weight (70 %) and are premature (70 %).

They may also have malrotation (54 %), multiple intestinal atresias, and an increased number of other associated anomalies that increase the prevalence of complications (63 %) and mortality rate (54–71 %).

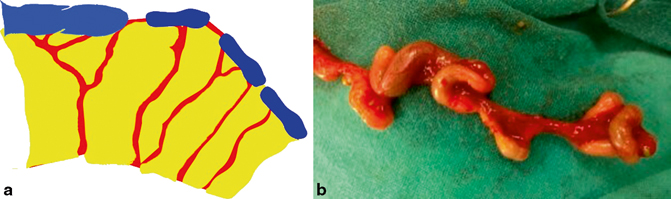

Fig. 23.6

Diagrammatic (a) and operative (b) representation of type IV atresia

Fig. 23.7

Intraoperative photograph showing type IV atresia

Type IV involves multiple small-bowel atresias of any combination of types I–III.

This defect has the appearance of a string of sausages because of the multiple lesions.

This type of intestinal atresia may occur in several members of the same family which suggest a possible autosomal recessive transmission.

Multiple intestinal atresias have been reported in association with cystic dilatation of the bile ducts.

Multiple intestinal atresias have also been reported in rare association with pyloric atresia and pylorocholedochal fistula.

The intestinal length is invariably and considerably shortened.

Pathophysiology

In small intestinal atresias, the ileum (55 %) is slightly affected more than the jejunum (45 %).

In more than 90 % of patients, the atresia is single; however, multiple atresias are reported in 6–20 % of cases.

Jejunoileal atresia can be associated with:

Intrauterine volvulus (27 %)

Gastroschisis (16 %)

Meconium ileus (12 %)

Sixty-two percent of atresia and stenosis cases were noted in the jejunum, 30 % in the ileum, and 8 % in both the jejunum and the ileum.

The frequency of atresia is as follows:

Stenosis (7 %)

Type I atresia (16 %)

Type II atresia (21 %)

Type IIIa atresia (24 %)

Type IIIb atresia (10 %)

Type IV atresia (22 %)

The mean birth weight and gestational age are significantly lower in patients with jejunal atresia than in those with ileal atresia.

Most jejunal atresias were multiple, whereas most ileal atresias were single.

Antenatal perforation is seen more frequently in ileal atresia but less in jejunal atresia.

The postoperative course is often prolonged, and the mortality rate is more in patients with jejunal atresia.

Clinical Features

History of polyhydramnios during prenatal ultrasonographic evaluation is common (30 %). This is more in those with upper jejunal atresia.

Prematurity (35 %). This is more in those with jejunal atresia.

Low birth weight (25 –50 %). This is more in those with jejunal atresia.

Bilious vomiting. The more proximal the obstruction the more is the vomiting.

Abdominal distension. This is more common in those with distal obstruction (Fig. 23.8).

Fig. 23.8

Clinical photograph showing severe abdominal distension in a patient with low intestinal obstruction

Jaundice (30 %). This is secondary to indirect hyperbilirubinemia and it is more in those with ileal atresia.

Failure to pass meconium in the first day of life. The passage of meconium does not however rule out intestinal atresia.

Clinically, intestinal loops as well as peristalsis may be visible.

An excessively dilated proximal bowel segment may undergo torsion, necrosis, and/or perforation. In these cases, the patient appears septic and dehydrated, and the abdominal wall may be erythematous.

Clinically, neonates with a proximal atresia develop bilious vomiting within hours, whereas patients with more distal obstruction may take longer to start vomiting.

A normal or scaphoid like abdomen in a neonate with bilious vomiting is indicative of a proximal obstruction.

Abdominal distension is more marked in those with distal obstruction.

Diagnosis

Antenatal ultrasound :

The diagnosis of intestinal atresias should be suspected antenatally during a routine ultrasound when it shows a dilated intestinal segment.

This is specially so in the presence of polyhydramnios.

These abnormalities are indicative of intestinal obstruction.

Persistently dilated bowel loops on serial ultrasounds have shown a 66.7 % positive correlation with intestinal atresia diagnosed after birth. This more so in those with proximal atresia.

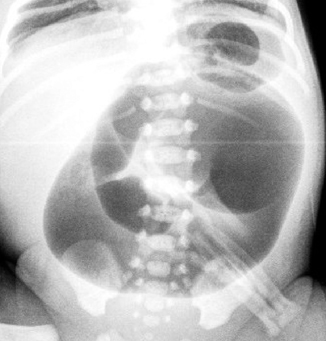

Plain abdominal x-ray (Fig. 23.9):

Fig. 23.9

Plain abdominal x-ray showing dilated bowel loops and absent gas distally indicative of intestinal obstruction

Plain abdominal radiograph of a newborn patient with small-bowel atresia demonstrates diffuse bowel distension, with gasless pelvis and air–fluid levels.

The more distal the obstruction, the more is the gaseous distension.

With more proximal atresias, few air–fluid levels are seen with no apparent gas in the lower part of the abdomen.

The more distal the obstruction, the more air–fluid levels are seen and distal intestine remains gasless.

In jejunal atresia, plain abdominal radiograph reveals a dilated gastric bubble and a massively dilated duodenum and proximal jejunum with a gasless abdomen distal to the level of the obstruction.

Peritoneal calcifications, seen in 12 % of patients, suggest meconium peritonitis, asign of in utero intestinal perforation.

Stenosis in a neonate is difficult to diagnose and it may not manifest for some time. These patients have a history of intermittent vomiting and failure to thrive. An upper gastrointestinal study with small-bowel follow-through is indicated in these patients.

Barium enema (Fig. 23.10):

Fig. 23.10

Barium enema showing small unused colon

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree