Congenital Anomalies of the Anorectum

Casey M. Calkins and Manu R. Sood

The spectrum of anorectal malformations (ARMs) ranges from anal stenosis to persistent cloaca. The term imperforate anus applies to most of these malformations because the anal canal is malformed and there is no visible normal anal opening onto the perineum. Anorectal anomalies occur in as many as one in 4000 live births and are slightly more common in boys. The most common defect is an imperforate anus with a fistula between the distal anorectum and the urethra in boys, or the vestibule in girls. The risk of a second child with an anorectal malformation is approximately 1%.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The embryologic development of the hindgut is discussed in Chapter 381. By 6 weeks of gestation, the urorectal septum divides the cloaca into the anterior urogenital sinus and posterior anorectal canal. Failure of the urorectal septum to form results in a fistula between the bowel and urinary tract (male) or the vagina or vestibule (female). Breakdown of the cloacal folds results in the external anal opening being anterior to the external sphincter (ie, anteriorly displaced anus or perineal fistula).

CLINICAL FEATURES AND DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

CLINICAL FEATURES AND DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

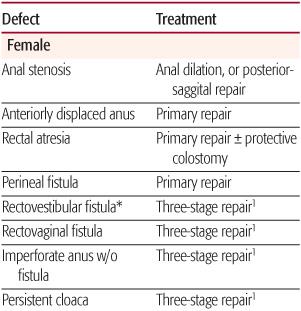

Anorectal malformations represent a wide spectrum of defects and should be ultimately described in terms of the realized anatomy, rather than “low or high” as is often customary (Table 415-1). The terms high or low, are used to generalize the location of the distal rectum or anal canal relative to the perineum. High lesions are those in which the rectum ends above the levator musculature and may or may not have a fistulous connection to the vagina, prostatic urethra, bladder neck, or bladder. Intermediate lesions are characterized by the rectal pouch ending within the levator complex, with or without a fistula to the vestibule or the bulbar urethra in boys. In low lesions, the rectal pouch has completely traversed the levator musculature, and a fistula usually is evident on the skin within the midline (perineal fistula). Rectal atresia refers to an unusual lesion in which the lumen of the rectum is either completely or partially interrupted, with the upper rectum being dilated and the lower rectum consisting of a small anal canal. Anal stenosis can be seen in both males and females and is characterized by a normally positioned anal perineal orifice with a narrowed anal canal. A persistent cloaca is a female defect in which the rectum, vagina, and urethra all empty into a single, common channel.

Table 415-1. Treatment of Congenital Anomalies of the Anorectum

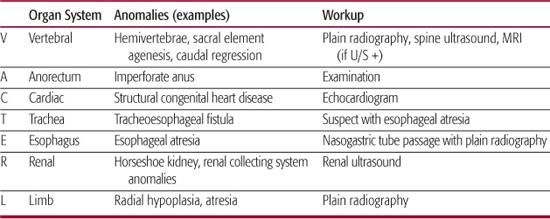

When evaluating the neonate with an anorectal malformation, a meticulous perineal inspection and thorough physical examination are crucial (eFig. 415.1  ). The examiner should recognize the fact that congenital anorectal anomalies often coexist with other lesions, and the VACTERL association must be considered (Table 415-2). Bony abnormalities of the sacrum and spine occur in about one third of patients with anorectal anomalies and consist of absent, accessory, or hemivertebrae or an asymmetric or short sacrum. The absence of two or more sacral elements is associated with a poor prognosis for bowel or bladder continence. Occult dysraphism of the spinal cord also may be present—tethered cord, lipomeningocele, or fat within the filum. Genitourinary abnormalities other than the rectourinary fistula occur in 26% to 59% of patients. Vesicoureteral reflux and hydronephrosis are the most common abnormalities, but other findings such as horseshoe, dysplastic, or absent kidney as well as hypospadias or cryptorchidism must also be sought. In general, the “higher” the anorectal malformation, the more frequent the associated urologic abnormalities. In patients with persistent cloaca or rectovesical fistula, the likelihood of a genitourinary abnormality is approximately 90%. In contrast, the frequency is only 10% in children with “low” defects (ie, perineal fistula).

). The examiner should recognize the fact that congenital anorectal anomalies often coexist with other lesions, and the VACTERL association must be considered (Table 415-2). Bony abnormalities of the sacrum and spine occur in about one third of patients with anorectal anomalies and consist of absent, accessory, or hemivertebrae or an asymmetric or short sacrum. The absence of two or more sacral elements is associated with a poor prognosis for bowel or bladder continence. Occult dysraphism of the spinal cord also may be present—tethered cord, lipomeningocele, or fat within the filum. Genitourinary abnormalities other than the rectourinary fistula occur in 26% to 59% of patients. Vesicoureteral reflux and hydronephrosis are the most common abnormalities, but other findings such as horseshoe, dysplastic, or absent kidney as well as hypospadias or cryptorchidism must also be sought. In general, the “higher” the anorectal malformation, the more frequent the associated urologic abnormalities. In patients with persistent cloaca or rectovesical fistula, the likelihood of a genitourinary abnormality is approximately 90%. In contrast, the frequency is only 10% in children with “low” defects (ie, perineal fistula).

Evaluation for associated anomalies mandates a thorough radiographic workup prior to definitive surgical management. Plain-film radiography is performed to evaluate for bony abnormalities of the vertebrae, sacrum, and limbs. Echocardiography should be performed in every infant to exclude structural congenital heart disease. Ultrasonography of the spine is obtained to exclude occult spinal dysraphism, and if an abnormality is noted, neuro-surgical consultation should be obtained.1 Before feeding, a nasogastric tube should be placed, and its presence within the stomach should be confirmed to exclude esophageal atresia. Radiographic evaluation of the urinary tract should include renal ultrasonography and a voiding cystourethrogram if clinically indicated. The latter should be obtained in every infant with a high or complex malformation.

Pediatric surgical consultation should be sought promptly when faced with a neonate with an anorectal malformation. In experienced hands, inspection of the perineum alone determines the level of the distal rectum in 80% of boys and 90% of girls. In the male, the generally accepted distance that would allow for safe primary repair is 1 cm or less. A cross-table lateral radiograph with the infant in the prone position and a radiopaque marker on the perineal skin will allow for this determination in some cases. Alternatively, ultrasonography can be utilized to achieve the same goal when experienced personnel are available to perform the examination. If primary repair is not performed, a colostomy is performed followed by a definitive repair 1 month after colostomy or when other anomalies have been adequately addressed or corrected.

Table 415-2. Evaluation for VACTERL Association

Evaluation of a female with an anorectal anomaly requires a thorough perineal inspection to differentiate between a cloaca, vestibular fistula, perineal fistula, or an anteriorly displaced anus. A single perineal orifice is consistent with a persistent cloaca and should always prompt a diverting colostomy. In females with a vestibular fistula, primary neonatal repair should be reserved for those with extensive primary surgical correction of the defect.2 Most pediatric surgeons, despite their level of experience, perform a diverting colostomy with the expectation to perform definitive repair several months later owing to the technical difficulty of separating the rectum from the vagina and the complications that may be realized if that portion of the operation is compromised.

SURGICAL TREATMENT

SURGICAL TREATMENT

The newborn infant with anal stenosis, perineal fistula, or an anteriorly displaced anus can usually undergo a primary, single-stage procedure without a colostomy. Three basic approaches may be used. For anal stenosis, simple dilatation is often successful. Initially, a dilator size is chosen commensurate with what the anal canal will accommodate without significant trauma to the anal canal. Dilations proceed twice daily, and the size of dilator is progressively increased at regular intervals under the guidance of a pediatric surgeon. The frequency of dilation is tapered and discontinued after the appropriate anal canal diameter is achieved (12-Fr size for infants—about the size of the adult index finger).

If there is a very small distance from the anal opening and the center of the external sphincter, and the perineal body (the distance between the most inferior aspect of the introitus in a female and the most posterior aspect of the scrotal raphe in a male) is intact and of adequate length, a cutback anoplasty is performed. An incision is made posteriorly from the anal orifice through the central part of the anal sphincter. A posterior anoplasty is performed and this effectively enlarges the anal opening. Alternatively, if there is a large distance between the anal opening and the central portion of the external anal sphincter or the perineal body is short, an anal transposition, or minimal posterior sagital anorectoplasty is performed.

Patients with other anorectal malformations require an initial colostomy, as the first part of a three-stage reconstruction. The colon is completely divided in the sigmoid region, with the proximal bowel as the colostomy and the distal bowel as a mucous fistula. The second-stage of the procedure usually is performed 1 to 6 months later, depending on the nature of the anomaly and the overall status of the patient. Definitive reconstruction consists of surgically dividing the fistulous connection with the urinary tract or vagina if present and pulling the terminal rectal pouch through the anal sphincter mechanism to the normal anal position with a procedure known as a posterior-sagital anorectoplasty. The central position of the anal sphincter is identified by electrical stimulation of the perineum.3 Two weeks after the anorectoplasty, a program of anal dilatations is started. Once the desired size is reached, the “third stage” of the operative plan is completed—colostomy closure. Dilations must be continued until the appropriate size can be passed easily, and they are thereafter tapered over the course of several weeks.

PROGNOSIS AND OUTCOMES

PROGNOSIS AND OUTCOMES

Fecal continence is the principal goal of the surgical repair of any anorectal malformation. The most common postoperative sequelae seen in children with these malformations include constipation, soiling, and incontinence. Prognostic factors for continence include the level of the rectum and whether the sacrum is normal. In general, the best results with regard to continence are seen in patients with low lesions and a normal sacrum.

Children who are completely free of soiling and have voluntary bowel movements are deemed totally continent. Although most children do not begin toilet training until 2 to 3 years of age, prior signs allow one to predict the possibility of successful continence in these children. Good prognostic signs include 1 to 3 bowel movements a day without interval soiling, evidence of sensation while defecating (pushing or making faces), a normal sacrum, well-formed and contoured buttocks, and urinary control. Ultimately, each patient must be treated individually based on the anatomy of the defect and the patient’s functional outcome.

Children with perineal fistula, rectal atresia, anteriorly displaced anus, and rectovestibular fistula have a high likelihood of total continence but more commonly experience constipation. This may result from a history of discomfort or pain during passage of bowel movements leading to a learned behavior with contraction of the pelvic floor to prevent the stool from passing. A downward spiral of constipation, overflow-soiling, mega-sigmoid, and dysmotility can ensue. Ensuring soft, painless, and regular bowel movements is important to prevent withholding behavior. Treatment strategies for patients with constipation and overflow incontinence are similar to those discussed in Chapter 386. In children with constipation but without withholding behavior, it is important to assure that there is no anatomic obstruction from stenosis at the anastomosis or incontinence via a fistula (digital examination or barium enema).

The parents of children with poor-prognosis defects should be educated about the expected outcome. Bowel-management techniques should focus on a goal of social continence, similar to strategies used for patients with spinal anomalies. Management strategies include the use of loperamide to slow the bowel transit and the frequency of fecal incontinence episodes, especially during the daytime.4-6

Children with rectoprostatic urethral fistula, rectovesicular fistula, or complex cloaca are more prone to incontinence and are often reliant on a bowel-management program to prevent fecal incontinence and social isolation. In general, this program utilizes maneuvers to keep the colon clean throughout the day while controlling the need to defecate, including retrograde or anterograde enemas (following placement of a cecostomy or appendicostomy).7 Anorectal biofeedback may improve continence in some older children with low to intermediate lesions and good sphincter function.

REFERENCES

See references on DVD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree