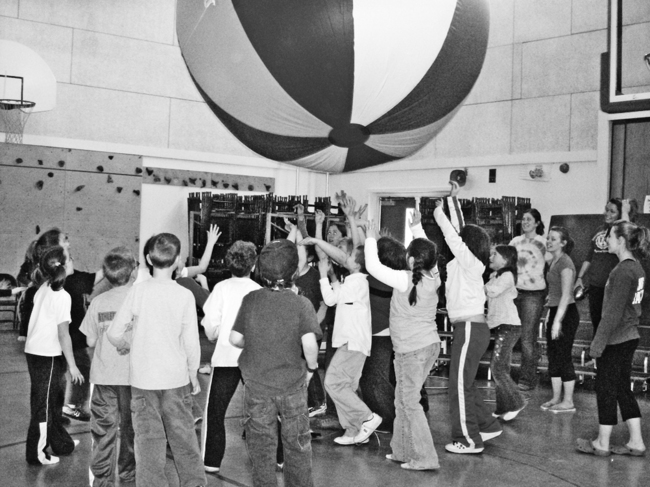

5 After studying this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following: • Understand the difference between community-based practice and community-built practice. • Understand the importance of therapeutic use of self in providing services in the community and in building community partnerships. • Identify the different service delivery methods occupational therapy practitioners may utilize in community settings. • Identify the different community systems in which occupational therapy practitioners work. • Understand the influence of public health on community interventions. • Identify the challenges to providing services in the community. The delivery of occupational therapy (OT) services has expanded far beyond the traditional medical model that served the majority of clients in the past. As health care expands to meet the unique needs of an increasingly diverse society, the treatment setting has changed in order to address the needs of the clients more efficiently. This requires OT services to be provided in a community setting in which the child lives, learns, plays, or is otherwise occupationally engaged. It should be a setting that is accessible and appropriate for the client and which allows for successful intervention to occur (Figure 5-1). In order to understand how clinicians practice in these settings and how this may differ from traditional hospital-based practice, it is necessary to define a community. Understandably, community is a broad term with many definitions. One definition of community is “a person’s natural environment, that is, where the person works, plays and performs other daily activities.”22 Another definition for community is “an area with geographic and often political boundaries demarcated as a district, county, metropolitan area, city, township, or neighborhood . . . a place where members have a sense of identity and belonging, shared values, norms, communication, and helping patterns.”9 Two definitions to articulate service delivery models help further understand the practice of OT in community systems. Community-based practice is defined as “skilled services delivered by health practitioners using an interactive model with clients” and community-built practice is “defined when skilled services are delivered by health practitioners using a collaborative and interactive model with clients.”22 Community-based practice is initiated by the medical model and results from referrals from other health care workers. Community-built practice has a public health perspective that focuses on health promotion and education. Treatment involves defining the community and working with the community in a variety of ways to support the client and enhance occupational functioning (Figure 5-2). While both types of community practice emphasize an interactive model, it is community-built practice that involves collaboration and a strong emphasis on empowerment and wellness.22 It is imperative that the OT clinician be aware of the community systems in which the client is engaged. Even if services are not provided in the context of a community agency, the environmental implications of the communities in which the child interacts on a daily basis must be considered to allow for optimal occupational functioning and health. The definition of health provided by the World Health Organization states that “health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”23 In order to promote optimal health in the child or adolescent, the practitioner needs to understand the community in which the child functions and understand how community systems and community resources can support successful occupational functioning. The definition of clients by the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process, 2nd edition, includes not only individuals but also organizations and populations within a community.1 Thus, when the client is a child referred for treatment, the context and environment must be considered as part of the domain of OT. Specifically, the social environment includes the community organizations and groups that are a part of and that affect the child’s occupational performance, and the context in which the child interacts with these community systems must be considered in order to provide effective treatment.1 Herzberg emphasizes the declining trend of health care provided in traditional inpatient and outpatient medical model settings and the growing trend of health care services offered in a community environment or through a community agency.10 A variety of perspectives on community interventions are therefore presented here, and the need for OT practitioners to develop the skills for working in communities to enhance full inclusion and social participation for the individual is also discussed. The OT practitioner is required to have certain community service skills, including consultation, policy-making, and program development skills. Defining who the client is may result in the community agency being the client; it may be necessary to broaden the definition of client to include the community at large that is supporting the client in order to provide the most effective OT services to the individual client. The distinction between community-based practice and community-built practice is discussed in the context of how the role of the OT practitioner will differ depending on the focus of the community organization. Here, the focus of community-based practice is considered to be the delivery of skilled services and addressing the client’s deficits by direct intervention in a community setting. Likewise, community-built practice involves the delivery of skilled services in collaboration with and with support from the appropriate community resources and the building of a sense of client empowerment to resolve client-defined issues. The need for both types of community practice is strongly emphasized, and the two approaches are viewed as existing on a continuum. OT practitioners are encouraged to expand their services to include roles on this continuum and roles that are focused in community environments.10 While the move toward greater awareness and involvement in community systems is generally perceived as a positive trend in health care, the OT practitioner should be mindful of the possible negative perceptions of the recipients of these types of services. Silverstein, Lamberto, DePeau, and Grossman unexpectedly found that low-income parents of children receiving multiple community and social services had negative experiences and perceptions of the community resources they utilized.16 Qualitative analysis of 41 interviews revealed parental perceptions of the need to make important decisions based on choices that were often less than satisfactory. A lack of control was experienced by parents when they had to accept community services that were sometimes seen as being ineffective due to lack of individualization. Employees of community agencies were sometimes perceived as being judgmental or too personal; these parents also felt sometimes that they had to compromise on their value systems. It is essential for occupational therapists and OTAs to practice effective therapeutic use of self when engaging with clients, their families, and individuals within the client’s community health care system. Therapeutic use of self has been defined as the therapist’s “planned use of his or her personality, insights, perceptions, and judgments as part of the therapeutic process”15 and conscious use of self in therapy as “the use of oneself in such a way that one becomes an effective tool in the evaluation and intervention process.”13 Effective therapeutic use of self requires the practitioner to have a thorough self-understanding of personal values and expectations as well as an understanding of the client’s values and cultural needs. Understanding how to negotiate a relationship most effectively by using personal skills to an advantage, while respecting the client’s values and beliefs, is a skill that one must develop in order to be an effective practitioner. When working with children, the relationship between the practitioner and the child’s caretaker(s) must also be considered. In community settings, other individuals such as teachers or community resource providers may be involved in the child’s care, too. It therefore becomes a multilayer network of relationships that must be nurtured and developed to ensure the best outcomes for the child or adolescent. The relationships between the practitioner and these individuals need to be taken into account to ensure the most effective treatment for the child. Therefore, OT practitioners working with children in community settings need to have excellent communication and negotiation skills as well as the ability to network with others to establish effective resources for each child. Furthermore, all of this requires a thorough understanding of the mission of the community system in which the child is engaged and how this mission relates to the services being provided by OT. Therapeutic relationship has been defined as “a trusting connection and rapport established between practitioner and client through collaboration, communication, therapist empathy, and mutual respect.8 The intentional relationship model is a conceptual practice model that thoroughly explains the relationship between the practitioner and the client.18 This model is specific to the field of OT and explores in detail how the therapeutic use of self promotes occupational engagement that facilitates a positive therapeutic relationship and thus successful therapy outcomes. One aspect of the model is an understanding of one’s therapeutic modes. In all, there are six therapeutic modes that a practitioner may utilize. A therapeutic mode is defined as an interacting style that a practitioner employs when working with a client. A practitioner may employ more than one mode, and the use of these modes is a function of the individual’s innate personality traits and natural communication style. The modes identified in this model include advocating, collaborating, empathizing, encouraging, instructing, and problem-solving. Ideally, a practitioner strives to acquire the ability to use all of the modes and to recognize which mode is the most appropriate to use in a given situation.18

Community systems

Community-based practice and community-built practice

Therapeutic use of self

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Community systems

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue