General Considerations

Patients may seek a sexually transmitted disease (STD) evaluation for essentially anything they perceive as abnormal and that is located “below the belt.” Although the presence of an STD should always be considered and ruled out, many patients who seek care for a suspected STD have nonsexually transmitted genital conditions. For this reason, clinicians should have a basic understanding of the spectrum of both normal skin findings and common dermatologic conditions that arise in the genitalia so they can prescribe appropriate therapy, refer the patient to a dermatologist for additional evaluation and management when necessary, or provide reassurance.

This chapter discusses the nonsexually transmitted dermatologic conditions most commonly encountered in the STD clinic setting, as well as normal variants. The discussion of pathologic lesions that follows is organized by morphology and color of lesion. A review of definitions employed to describe skin lesions is found in Table 30–1. A section on ectoparasites concludes the chapter. For a more comprehensive review of genital dermatology, the reader is referred to the text references listed below.

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Macule | Area of color change <1.5 cm and smooth |

| Patch | Area of color change >1.5 cm and smooth |

| Papule | Palpable lesion <1 cm |

| Plaque | Palpable lesion >1 cm |

| Nodule | Papule or plaque with deeper extension into the skin |

| Scale | Abnormal shedding or accumulation of cornified cells |

| Vesicle | Blister <1 cm |

| Bulla | Blister >1 cm |

| Pustule | Pus-filled vesicle |

| Erosion | Shallow skin defect |

| Ulcer | Deep skin defect |

| Crust | Amorphous accumulation of dried serum, pus, or blood |

History

A thorough history is an essential component in the evaluation of an individual presenting with genital lesions or rash. Useful questions to ask include the following:

- (1) How long has the lesion or rash been present? The duration of a genital lesion is important for directing evaluation. For example, a genital ulcer or atypical lesion that has been slowly growing over the course of months to years implies the need for immediate biopsy, whereas an ulcer of shorter duration (that does not appear atypical) may warrant a workup for common infectious etiologies, and perhaps empiric therapy, with biopsy reserved for situations in which the workup is negative and the lesion fails to resolve.

- (2) Does the lesion look the same now as it did when it first appeared? If not, how is it different? Understanding the evolution of a lesion or rash may assist the clinician in narrowing the differential diagnosis. For example, a patient may have self-treated a herpes simplex virus infection, resulting in a contact dermatitis. Only a thorough history will allow the clinician to sift through the details and put the story together.

- (3) What other areas are involved? Are the abnormalities confined to the genital region or widespread? In general, disseminated rashes require more urgent evaluation than localized rashes, particularly if accompanied by systemic signs and symptoms. In addition, syphilis should always be considered in the evaluation of a disseminated rash (see Chapter 19).

- (4) What are the characteristics of the rash or lesion? Was the onset of the rash or lesion associated with anything in particular? A pruritic rash may imply an ectoparasitic infection or a drug reaction, whereas a genital rash that stings and burns may be a result of contact dermatitis. In the case of irritant contact dermatitis, the patient may recall the close temporal relationship between application of an offending product and symptom onset.

- (5) Has this ever happened to you before? If so, what was determined to be the cause that time? Fixed drug eruption, a lesion that occurs at the same anatomic site (and worsens) with each exposure to the drug, would often escape diagnosis unless the clinician elicited a previous history. Likewise, a patient with a widespread dermatosis, such as psoriasis, may have experienced genital lesions in the past.

- (6) What are your hygiene habits? What products does your partner use? Do you use condoms, lubricants, or spermicides when you have sex? It is often helpful to address issues of personal hygiene and sexual practice in an open-ended fashion, followed by more pointed questions. At times it may be necessary to ask patients to review their daily hygiene routine with the clinician as this may jog their memories.

Normal Anatomic Variants

When a patient presents for initial evaluation of a genital condition, one of the first issues to consider is whether or not the abnormality in question is pathologic or simply a normal variant. This distinction is important, because intervention involving a normal anatomic variant often is not in the best interest of the patient. Among the commonly encountered normal variants are pearly penile papules, vestibular papillae, and Fordyce spots.

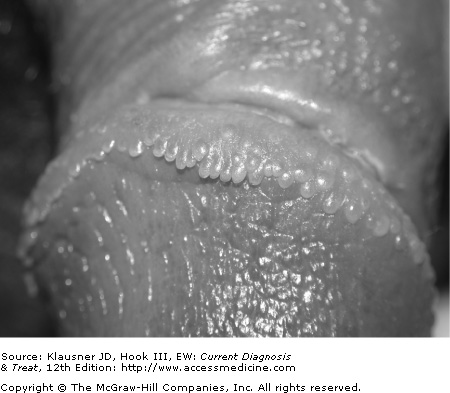

- • Skin-colored papules most commonly located in the coronal sulcus of the penis.

- • Asymptomatic papules with rounded tips and discrete bases.

One of the most commonly encountered dermatologic conditions in male patients who seek care at STD clinics, pearly penile papules are usually brought to the attention of the clinician when the patient presents for evaluation of possible condylomata acuminata. The papules are found more commonly in uncircumcised men and are located primarily around the coronal sulcus. They may also be found on the distal penile shaft, near the frenulum, or on the posterior part of the glans penis. These asymptomatic lesions are usually flesh-colored or pink and rounded with discrete bases. They may be elongated into papillae (see Figure 30–1).

The primary entity with which pearly penile papules are confused is condylomata acuminata. Unlike pearly penile papules, however, condylomata acuminata often have spiked tips or are contiguous at the base.

The diagnosis of pearly penile papules is based on the clinical appearance. Biopsy is usually not necessary but, if performed, would reveal a benign angiofibroma. Reassurance is the only treatment necessary.

- • Asymptomatic, small, monomorphous, symmetric tubular papillae located within the vaginal vestibule.

- • Often confused with condylomata acuminata.

Vestibular papillae occur in one third to one half of women and are a normal anatomic variant distinguished by monomorphic appearance, rounded tips, discrete nature of the base of the lesions, and symmetric distribution. Some variants of vestibular papillae are short and confluent, giving a cobblestone texture to the skin. These lesions are typically found in the vaginal vestibule and are asymptomatic. Although there is some debate as to the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) in the development of vestibular papillae, the current consensus is that HPV is not related to these lesions.

The primary entity with which vestibular papillae are confused is condylomata acuminata. The two conditions can usually be distinguished from one another based on the appearance of the lesions.

The diagnosis of vestibular papillae is based on the appearance and distribution of the lesions. Application of acetic acid 5% does not reliably distinguish these lesions from genital warts. Other than reassuring the patient, no treatment is necessary.

- • Flesh-colored to yellowish, small, smooth papules.

- • Most commonly located on the medial aspect of the labia minora or the proximal quarter of the penile shaft.

Fordyce spots are enlarged sebaceous glands located on modified mucous membranes that typically involve the medial aspect of the labia minora in women and the proximal quarter of the penile shaft in men. They are asymptomatic, papular, and flesh-colored to yellow in appearance (see Figure 30–2). They may be discrete and multilobular or confluent.

No laboratory studies are necessary; diagnosis is based on clinical appearance. Although the appearance of Fordyce spots is characteristic, it may be possible to confuse them with small condylomata acuminata. No treatment is necessary.

Pathologic Lesions

- • Common viral infection characterized by flesh-colored, pearly papules with central umbilication.

- • Self-limited in immunocompetent hosts.

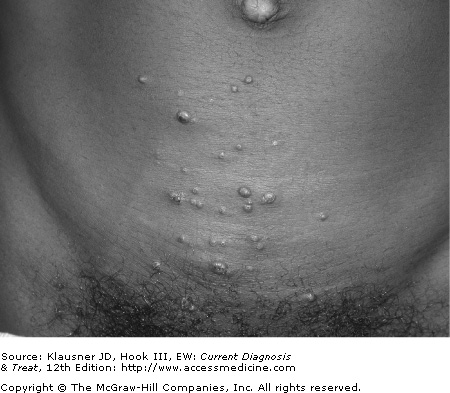

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by the molluscum contagiosum virus, a member of the DNA poxvirus group, and is common in children and young adults. It is usually transmitted through sexual and other close contact.

The infection is characterized by firm, dome-shaped, flesh-colored, “pearly” papules with central umbilication (see Figure 30–3). Although the classic central umbilication may not be present on all lesions, usually there are several on which this depression may be found. If the lesion of molluscum contagiosum is incised, a central core, usually waxy, can be expressed. The central umbilication and waxy core help differentiate molluscum contagiosum from other diseases. Lesions are most often asymptomatic but may be described as pruritic. They are most often located in the pubic area, proximal and medial thighs, and penile shaft. Lesions are larger and more numerous in immunosuppressed patients.

Biopsy is rarely required to diagnose molluscum contagiosum. If performed, histologic examination will reveal large eosinophilic inclusion bodies within epidermal cells.

Molluscum contagiosum may be confused with condylomata acuminata, and molluscum lesions that are more vesicular in appearance may be confused with herpes simplex virus. Sebaceous gland hyperplasia, basal cell carcinoma, and, in immunosuppressed individuals, fungal infections such as cryptococcosis and histoplasmosis should also be considered. If the patient presents with molluscum-like lesions in the setting of systemic symptoms, evaluation should proceed quickly to rule out disseminated fungal infection.

Although the course of infection in the immunocompetent host is usually self-limited, generally resolving over months, patients may desire treatment for cosmetic purposes. In contrast, molluscum contagiosum in the immunocompromised host is often persistent, larger, and more distressing to the patient in terms of appearance and often requires treatment.

Treatment requires either destructive or immunomodulatory modalities. Molluscum contagiosum can be effectively treated with curettage or incision followed by expression of the central white core of the lesion, also known as the “molluscum body.” Other therapeutic modalities include electrosurgery and cryotherapy. Cantharidin may be used for lesions found outside the genital region but, because of painful blisters and erythema that result from therapy, should be avoided in sensitive areas of the body. Recent studies have found variable success with imiquimod, applied three times a week overnight for up to 16 weeks; clearance rates have ranged from 33% to 100%, depending on the population studied. Finally, podophyllin, podofilox 0.5%, laser therapy, and trichloroacetic acid may be used.

Molluscum contagiosum is usually not eliminated in one treatment and lesions may continue to occur for a time after treatment. Relapse is particularly frequent in immunocompromised hosts.

- • Lesions are characterized by skin-colored, pink or white, flat-topped papules or plaques that may ulcerate over time.

- • Lesions typically are present for a year or longer.

The terminology describing squamous intraepithelial neoplasia has proved to be confusing at times to the nondermatologist. The histology of intraepithelial neoplasia is described using terminology similar to that used to describe Papanicolaou (Pap) smears and represents a spectrum from mild dysplasia of the epithelium to severe dysplasia (carcinoma in situ). The final step in this pathway is frankly invasive squamous cell carcinoma, which has metastatic capability. Vulvar involvement with intraepithelial neoplasia is referred to as vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, and penile involvement as penile intraepithelial neoplasia. There is currently a move to use this more general terminology and steer away from the terms used to describe various types of intraepithelial neoplasia that were used in the past that included, but were not limited to, Bowen’s disease, bowenoid papulosis, keratotic balanitis, and erythroplasia of Queyrat.

Multifocal intraepithelial neoplasia has been documented to occur in a slightly younger age group (20–40 years) than unifocal disease (typically >50 years) and is more likely to be linked to high-risk HPV types, primarily 16 and 18. Multifocal intraepithelial neoplasia is less likely to progress to frankly invasive squamous cell carcinoma, as compared with single lesion intraepithelial neoplasia.

Risk factors for the development of intraepithelial neoplasia include advanced age, smoking, and compromised immune status. The presence of a long-standing inflammatory dermatologic condition such as lichen sclerosis is a risk factor for the development of squamous cell carcinoma.

The appearance of intraepithelial neoplasia is variable, and lesions may be flesh-colored, red, or white. Multifocal intraepithelial neoplasia (formerly known as bowenoid papulosis) usually appears as multiple discrete flat-topped papules or plaques on the glans, prepuce, and penile shaft in men or the vestibule and outer labia minora in women. Single lesion intraepithelial neoplasia is usually a larger, well-defined patch or plaque with scale that may ulcerate over time. Some forms of intraepithelial neoplasia, especially after progression to squamous cell carcinoma, may appear more verrucous, become friable, and bleed easily (see Figure 30–4). Long-standing squamous cell carcinoma may result in destruction of the genitalia (see Figure 30–5).

The history is the key to the correct evaluation and diagnosis of patients with intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma. The time course of the lesion is long, often on order of years. The lesions are usually asymptomatic, although some patients may complain of pruritus, with growth so slow as to often be imperceptible.

The diagnosis of intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma should be confirmed by biopsy.

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and penile intraepithelial neoplasia may be confused with condylomata acuminata. Some forms of squamous cell carcinoma may be confused with granuloma inguinale (donovanosis). Biopsy can distinguish between these etiologies.

Treatment of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, penile intraepithelial neoplasia, and squamous cell carcinoma involves local destruction or removal of lesions. Patients should be referred to a dermatologist and may require referral to a gynecologist or urologist if the disease process is advanced.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree