Common Dysmorphic Syndromes

INTRODUCTION

Numerous genetic conditions are evident and diagnosable during the neonatal period because of a specific pattern of clinical features often present on infant physical examination. This chapter reviews several of the more frequently observed genetic dysmorphic conditions neonatal practitioners are most likely to encounter in a newborn (apart from the common trisomies that are addressed separately in this textbook), which include: Turner syndrome (TS), 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, CHARGE (coloboma, heart defect, atresia choanae [also known as choanal atresia], retarded growth and development, genital abnormality, and ear abnormality) syndrome, and VACTERL (vertebral, anal, cardiac, tracheoesophageal, renal, and limb) association.

As several genetic syndromes and 1 association are discussed in this chapter, it is reasonable to define both entities. The term syndrome derives from the Greek and means “concurrence” or “along with, together.” Thus, a genetic syndrome refers to a pattern of congenital anomalies that can be explained by a common genetic or developmental cause. Syndromes often include developmental abnormalities and increased risk of recurrence in families. An association is a collection of physical findings and is considered a nonrandom occurrence; it is known not be a polytypic defect, sequence, or syndrome.1 Associations are generally not associated with an increased risk of recurrence.1

Identification of a specific genetic diagnosis during the immediate newborn period is helpful for appropriate medical management, as well as to provide the infant’s family with prognostic information and accurate recurrence risk information.

CLINICAL GENETICS EVALUATION

Physical examination of the neonate is essential in providing diagnostic accuracy as well as focusing differential diagnoses. The genetic dysmorphology evaluation is a careful physical examination of the infant in a head-to-toe manner, taking note of any facial or body asymmetries, malformations, or deformations that may be present externally. This also involves measuring and plotting the growth parameters (length, weight, and head circumference) on appropriate curves for gestational age, such that entities of microcephaly or microsomia are not neglected.

The neonatal head is evaluated by assessing the head shape, size of the anterior and posterior fontanelles, and cranial sutures. Close attention is paid to possible sutural ridging or unusual head shape that is distinct from transient postnatal vertex molding. Careful evaluation of the scalp is performed to uncover lesions such as cutis aplasia congenita or unusual hair patterning that may indicate an underlying cerebral malformation. Facial asymmetry or cranial nerve palsy is best visualized while the infant is crying. Presence of facial asymmetry is often seen in association with syndromes such as CHARGE or 22q11.2 deletion syndrome and thus is of significant diagnostic value.

Evaluation of the eyes with an ophthalmoscope is warranted such that red reflexes can be visualized and irides can be closely examined for the presence of colobomas, which tend to be located inferonasally. Certain ophthalmic anomalies, such as iris Brushfield spots (observed in Down syndrome), retinal coloboma, optic nerve hypoplasia, and abnormal retinal pigmentation are not easily visualized by this methodology and require formal ophthalmology evaluation for detection.

Ears are analyzed for any unusual appearance of the concha, ear positioning, presence of preauricular pits or tags, or malformations such as microtia. The palate and lips are visualized for evidence of clefting, with close attention paid to the uvula to assess if there is a bifid formation or circumferential zona pellucida that could indicate a submucous cleft palate. An infant with frequent nasal regurgitation of feedings may have a submucous cleft or velopharyngeal insufficiency.

Nuchal skin redundancy with a low posterior hairline may be present in association with certain chromosome abnormalities, single-gene disorders, or in infants with complex congenital cardiac defects. If nuchal webbing is noted, close evaluation for limb edema indicating in utero lymphatic obstruction is also helpful diagnostically.

Examination of the limbs, hands, fingers, feet, toes, and palmar and plantar creases provides further insight as well as careful consideration for syndactyly, polydactyly, joint contractures, and limb positioning. Knowledge of a cardiac murmur, abdominal wall defects, hepatosplenomegaly, genitourinary anomalies, sacral dimple, or neural tube defects are essential and will guide the genetic diagnostic workup appropriately.

COMMON DYSMOPRHIC SYNDROMES

Turner Syndrome

Turner syndrome is a genetic condition caused by absence of all (monosomy) or part (partial monosomy) of the second X chromosome; thus, it only affects females. This multisystemic disorder has variable phenotypic severity, and in milder cases, this diagnosis may be overlooked during infancy, without detection until childhood or adolescence once short stature and pubertal delay are recognized.2

Turner syndrome has a birth prevalence of 1 in 2000 to 5000 female live births; however, the majority of 45,X concept uses spontaneously abort during the first trimester of pregnancy. TS-affected fetuses that survive into the second trimester are often recognized to have increased nuchal fold and lymphedema on prenatal ultrasound.3 At birth, affected neonates may present with a constellation of features of a variable phenotypic spectrum. Congenital cardiac defects may often be the sole manifesting feature. Abnormalities of the left outflow tract, such as bicuspid aortic valve, and coarctation of the aorta are commonly observed. Nuchal webbing, low posterior hairline, residual edema of the dorsum of the hands and plantar surfaces of the feet, and a shield-shaped chest with widely spaced nipples may be identified via careful newborn physical examination. The severity of these findings tends to depend on the degree of in utero lymphedema during embryologic development. Thus, mildly affected females may be diagnostically challenging.

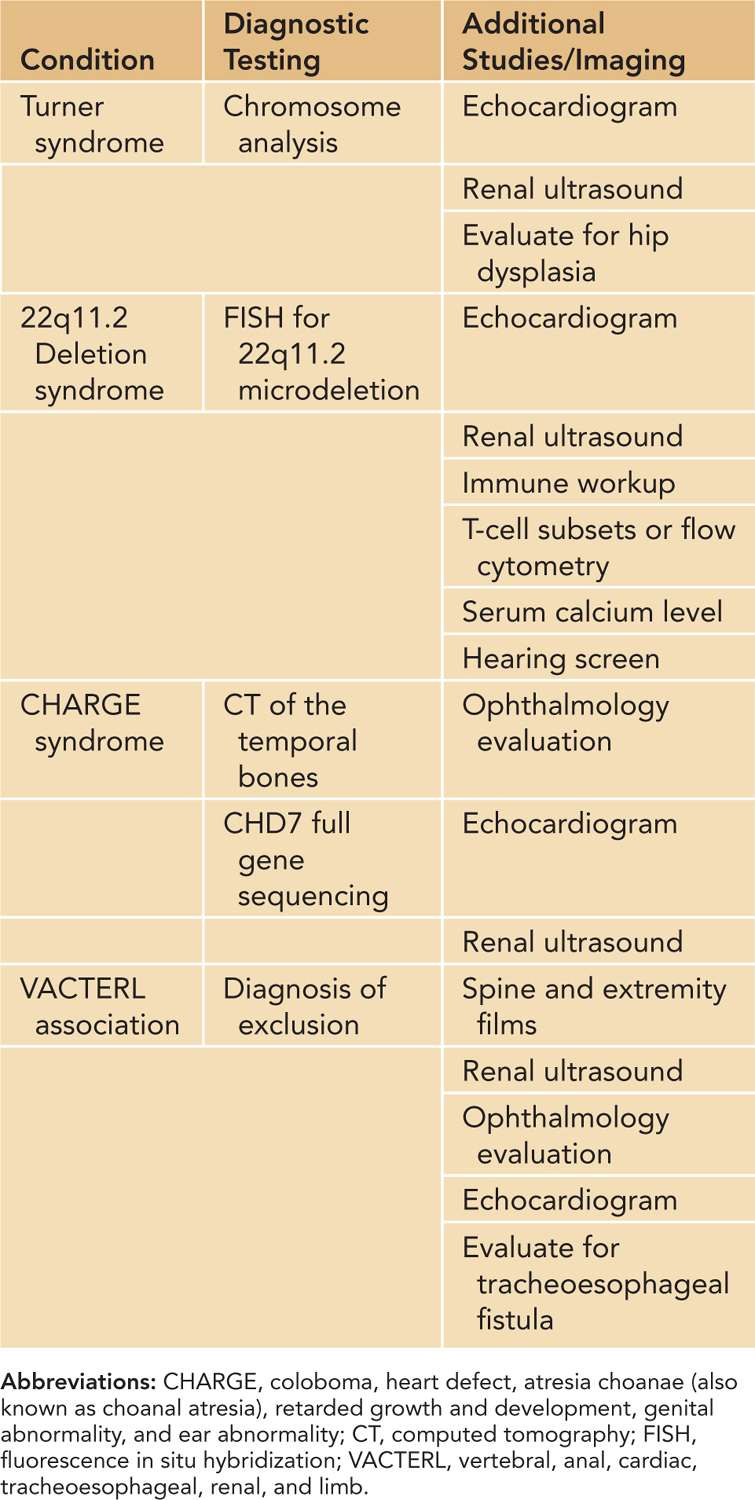

A number of different diagnostic tests can be performed on the female infant suspected to have TS: chromosome analysis from peripheral blood; echocardiogram to evaluate for congenital cardiac defects; and renal ultrasound to look for structural anomalies of the kidney or abnormalities of the renal collecting system.3 Furthermore, careful hip examination for congenital hip dysplasia and newborn hearing screen prior to discharge are recommended (Table 109-1).

Table 109-1 Diagnostic Testing for Genetic Dysmorphic Conditions Encountered in the Neonatal Period

Structural chromosome abnormalities such as isochromosome X, ring X, as well as deletions of a portion of the short arm (Xp) or long arm (Xq) have also been reported in females with TS.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree