Fig. 14.1

Overview of clinical management for precancerous cervical lesions. WHO World Health Organization, SIL squamous intraepithelial lesion, GIL glandular intraepithelial lesion, CIN1 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1, CIN2 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2, CIN3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3, LSIL low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, HSIL high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, AIS adenocarcinoma in situ

Conization

In the United States, conization of the uterine cervix is primarily performed as a diagnostic tool and secondarily as a therapeutic option in patients that are young and desire future fertility [11]. However, conization is used for definitive treatment in other countries. Cold-knife conization has been the standard treatment for precancerous lesions of the cervix for many years. Large conization is an effective option for lesion removal but carries an increased risk of complications.

In cervical HSIL , shallow conization capturing all abnormal tissue is preferred to large conization in patients desiring future fertility (Figs. 14.2a–c and 14.3). Colposcopy allows accurate assessment of lesion size prior to conization. In shallow conization , an incision is made in the mucous membrane of the ectocervix at a location and depth that is certain to include all abnormal lesions. Morphometric data indicate the vast majority of HSIL are less than 5 mm deep, suggesting treatments extending to a depth of around 1 cm are adequate in women with satisfactory colposcopy [37]. Although therapeutic conization should preferably be avoided in pregnant patients with HSIL, diagnostic shallow conization of the index lesion is recommended in pregnant women when microinvasive carcinoma is suspected from cervical smear, colposcopy, and/or biopsy findings [35] (Fig. 14.2d–f).

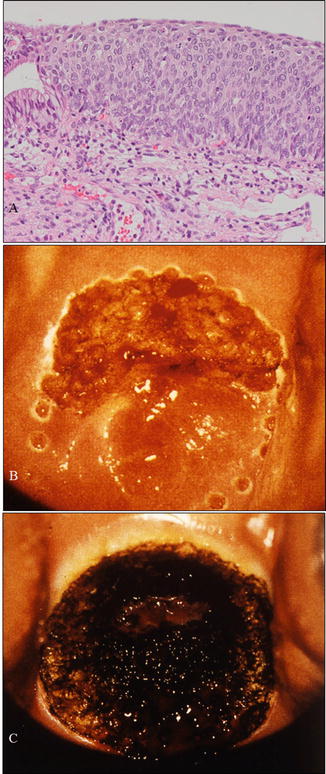

Fig. 14.2

Various shapes of conization. (a–c) Gross photography of a cervical specimen (a, front view; b, side view) obtained from therapeutic shallow conization involving a small incision (*) orientated at 12 o’clock and microphotography of the specimen (c) demonstrating HSIL. The patient was a 28-year-old woman, gravidity 1, parity 1, who wished for another baby. The patient became pregnant 3 months after this conization and delivered a healthy baby at 38 weeks of pregnancy. (d–f) Gross photography of a cervical specimen (d, front view; e, side view) obtained from diagnostic shallow conization during pregnancy and microphotography of the specimen (f) demonstrating HSIL. The patient was a 28 year-old woman, gravida 3, parity 2, at 21 weeks of pregnancy. Preoperatively, cervical smear and punch biopsies indicated HSIL with a suggestion of stromal invasion. Finally, HSIL without invasion (f) was confirmed by the diagnostic shallow conization, and the patient delivered a healthy baby at 39 weeks of pregnancy. (g–i) Gross photography of a cervical specimen (g, front view; h, side view) obtained from therapeutic cylindrical conization for AIS and microphotography of the specimen (i) demonstrated AIS at a localized area of the endocervix. The patient was a 34-year-old woman, gravidity 2, parity 2, who wished to preserve her fertility. Histological analysis and cervical cytological examination following conization indicated no residual cervical AIS (c, f, i: hematoxylin-eosin staining, magnification ×10 for c, f, i)

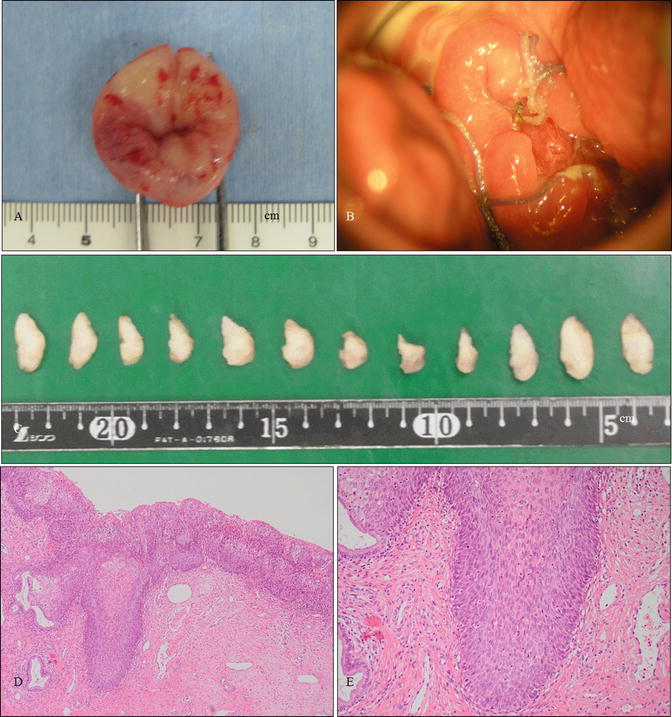

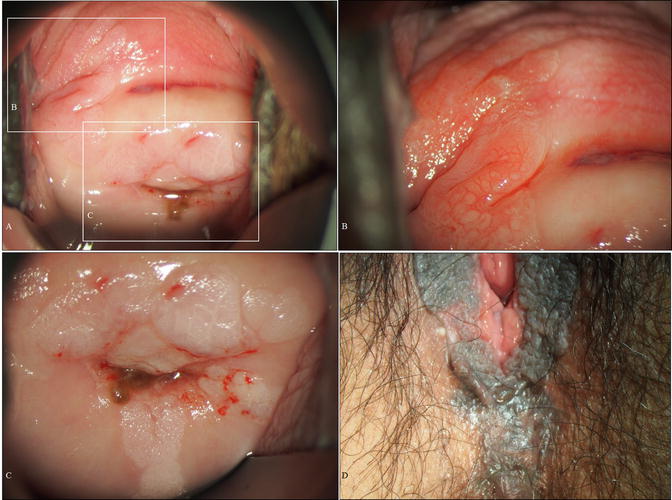

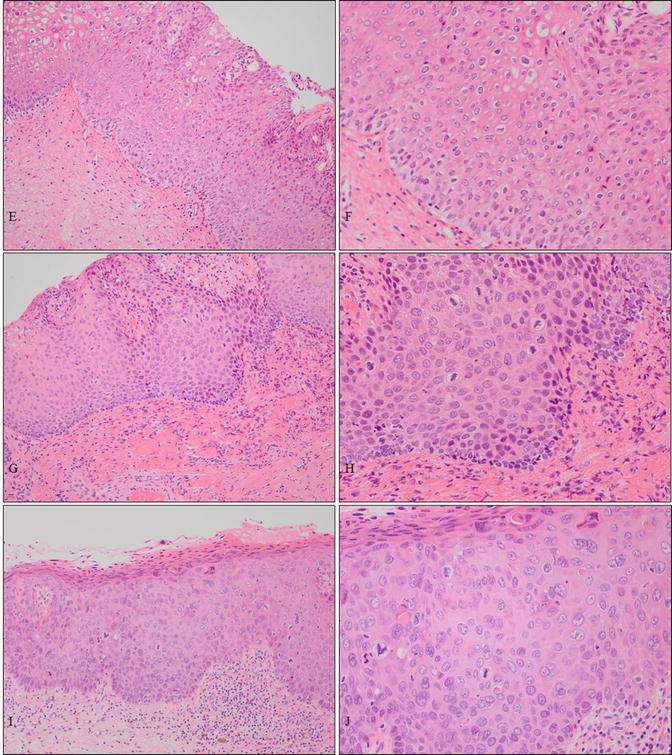

Fig. 14.3

Shallow conization in a case of cervical HSIL. (a, b) Gross photography of a specimen obtained from conization (a) and the cervix of the patient 1 month after conization (b). The patient was a 25-year-old woman, nulligravida, who had a 2-year history of cervical and vulvar HSIL referred to our hospital. The vulvar lesion is shown in Fig. 14.8. (c) Gross photography of the 12 divided specimens following formalin fixation for pathological analysis. (d, e) Microphotographs of cervical specimens demonstrating HSIL (d, e: hematoxylin and eosin staining, magnification ×4 for d and ×10 for e)

The demonstration of residual disease in subsequent hysterectomy specimens has been a major concern with the use of regular conization for cervical AIS. Residual AIS has been reported in up to half of patients with uninvolved margins of conization [38] and in up to 80 % of patients with involved margins [39]. Therefore, cylindrical and deep conization running parallel to the endocervical canal and including the transformation zone and deep glands is recommended as an alternative excisional option in the vast majority of AIS cases [15, 31] (Fig. 14.2g–i). Since cylindrical and deep conization confers a much higher risk of postconization cervical stenosis, techniques are required to prevent stenosis . The use of retained nylon threads tied to an intrauterine device reportedly prevents cervical stenosis [40]. Pathologic assessment of the length and depth of AIS involvement should be performed in order to ensure adequate removal of AIS lesions [41], and postconization endocervical curettage (ECC) which is performed above the conization bed after the excision would provide valuable prognostic information regarding the risk of residual AIS [42]. In addition, strong consideration should be given to high-risk HPV testing in conjunction with cervical cytology or ECC in light of recent data supporting its value in prediction of recurrent AIS [43–45].

Regarding reduction of operative hemorrhage during cornization, the most frequently used techniques are lateral suturing of the descending branches of the cervical arteries and direct injection of a vasopressor into the cervical stroma. The Sturmdorf method involving suturing of resultant raw surface flaps of cervical epithelium, is unnecessary in the majority of cases. Hemorrhage may occur as a result of incomplete division of the vessels, or it may be associated with secondary infection of the defect site. Treatment is usually conservative, although occasionally surgical management may be required. Significant cervical stenosis and infertility are rare complications dependent on the amount of endocervix removed. Conization is associated with adverse obstetric outcomes, including preterm delivery and perinatal mortality, with excision depth posited as a risk factor [37].

Carbon dioxide (CO2) lasers , “light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation,” may be utilized as an alternative to cold-knife conization to reduce the complication risk. Several studies have shown that rates of primary and secondary hemorrhage, and residual disease, are comparable between laser and cold-knife conizations and that compared with cold-knife conization, laser conization is associated with a statistically significant decrease in the risk of cervical stenosis and inadequate colposcopy at follow-up [1]. The major issue with laser conization is the difficulty in evaluating excised lesions and margins due to laser-induced coagulation [46]. Recently, conization using an ultrasonic scalpel has been shown to be a reliable method avoiding thermal artifacts associated with laser conization [47, 48].

Loop Electrosurgical Excision Procedure

LEEP is currently one of the most frequently used techniques for the effective eradication of cervical HSIL [49, 50]. An appropriately sized loop is chosen to encompass the entire lesion for removal in one block. The depth of the excised tissue varies; however, a depth of 6–7 mm is conventionally used. This technique provides adequate tissue for histopathological assessment. Large studies have demonstrated early invasive lesions not recognized by colposcopy may be identified with LEEP [51]. Thermal artifact is the most substantial issue with LEEP in general practice with approximately 10 % of specimens reported as unreadable and 30–50 % having significant coagulation artifact [46, 51]. The main side effect of LEEP is secondary hemorrhage, similar to conization. LEEP may cause cervical stenosis , occurring in approximately 6 % of cases. Previous loop excision and the volume of excised specimens have been shown to be independent predictors of stenosis [52]. Duggan et al. observed no difference in recurrence rates between LEEP and conization [53]. A prospective study found lower rates of preterm premature membrane rupture, preterm delivery, and low birth weight (<2500 g) with LEEP than with cold-knife conization and no difference in mean birth weight, cesarean delivery, labor induction, or neonatal intensive care unit admission [54].

Ablative Methods

Ablative techniques, including laser vaporization and cryotherapy, are second-choice treatments for cervical HSIL. CO2 laser vaporization is widely accepted as one of the most effective ablative treatments for cervical HSIL, and there is no evidence of differing outcomes between laser vaporization and excisional LEEP [55, 56] (Fig. 14.4). Cryosurgery , in use for the past four decades, is relatively simple and can be performed effectively in developing countries [57]. However, it is associated with a higher rate of subsequent morbidity, including invasive carcinoma, than laser vaporization and excisional methods [58, 59]. Ablative techniques preclude histological assessment as they destroy the epithelium of the transformation zone (Fig. 14.4). Prior to the use of ablative therapies, histological diagnosis by colposcopically directed biopsy should be undertaken in order to exclude invasive carcinoma [60]. The entire transformation zone and the lesion should be fully visible with colposcopy, and there should be concordance among all cytological, colposcopic, and histological findings. Ablative methods are appropriate in women with lower severity ectocervical HSIL and contraindicated by HSIL extending into the endocervical canal, AIS, and clinical suspicion of invasive carcinoma. Despite these reservations, laser vaporization provides control over the depth of destruction and hemostasis and improves healing with minimal damage to adjacent tissues. Laser vaporization also has utility in treating multiple HSILs in the lower genital tract , including the cervix, vagina, and vulva [11].

Fig. 14.4

A case with cervical HSIL treated by CO2 laser evaporation . (a) Microphotography of a biopsy sample demonstrating HSIL consistent with cytological and colposcopical findings. The patient was a 28-year-old woman, nulligravida, who hoped for a baby in the near future. (b) Margin of a planned area for vaporization marked using a laser beam. (c) Vaporization of the entire transformation zone including the HSIL using a CO2 laser beam (a: hematoxylin-eosin staining, magnification ×10)

Hysterectomy

Hysterectomy is indicated for cervical HSIL, particularly in postmenopausal patients or patients accepting of permanent sterilization. However, HSIL is not considered an appropriate sole indictor for hysterectomy as multiple alternative therapies are currently available. Conversely, hysterectomy has been proposed as the gold-standard treatment of AIS [39, 41]. Currently, there is a lack of consensus regarding the safety of conization alone for the treatment of AIS. In particular, hysterectomy should be considered when the residual AIS is identified following conization.

In patients requiring hysterectomy for definitive treatment of HSIL or AIS, vaginal hysterectomy or minimally invasive techniques such as a laparoscopic hysterectomy are appropriate in developed countries.

Clinical Management of the Vaginal Precancerous Lesion

Precancerous Lesion of the Vagina in This Chapter

1.

High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL). Synonyms: vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (VaIN2), grade 3 (VaIN3)

Clinical Management

Management of Patients with High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions

Diagnoses of primary vaginal carcinoma must satisfy the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) criteria, including sparing of the uterine cervix. According to these criteria, vaginal carcinoma is rare and affects older women aged greater than 60 years. The posterior wall of the upper third of the vagina is the most frequently involved site [61]. Coexistence of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN) and vaginal carcinoma is rare, comprising 0.4 % of all intraepithelial neoplasia affecting the lower female genital tract. VAIN has been shown to be associated with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) seen in up to 43 % of women [62–65]. VAIN reportedly occurs in the presence of multiple HPV-associated lesions affecting the lower genital anogenital tract. The natural history of VAIN is thought to be largely similar to that of CIN with high-grade VAIN considered a precancerous lesion [62, 66]. Although a three-tier system stratifying vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia into VAIN1, VAIN2, and VAIN3 categories has been previously widely used in clinical management, a two-tier system categorizing vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia as either LSIL or HSIL has recently been proposed and adopted in the newly released 2014 WHO classification [67]. It is, henceforth, anticipated that the new two-tier system will be adopted in the clinical management of VAIN.

Vaginal SILs are commonly asymptomatic. Cytologic screening is the conventional method of identifying the presence of vaginal SIL. The vagina should be carefully inspected by colposcopy for obvious abnormalities, with particular attention paid to the upper vagina. Vaginal HSIL commonly involves the upper third of the vagina or the vaginal vault following hysterectomy and is frequently multifocal involving other regions of the lower genital tract, termed “lower genital tract neoplastic syndrome ” (Fig. 14.5). Colposcopic examination and directed biopsy are the mainstays of accurate vaginal HSIL diagnosis. In typical colposcopic findings, vaginal HSILs are ovoid and slightly raised, exhibiting a thickened acetowhite epithelium and a raised external border. Lesions with a papillary surface or abnormal vascular patterns, such as punctuation or mosaic, should be examined by multiple biopsies to rule out invasive carcinoma [61] (Fig. 14.5). Colposcopy is often a poorer predictor of histological findings in vaginal SIL than in cervical SIL. Even in cases where colposcopy reveals mild and atrophic changes, histologic findings occasionally demonstrate more severe changes (Fig. 14.6).

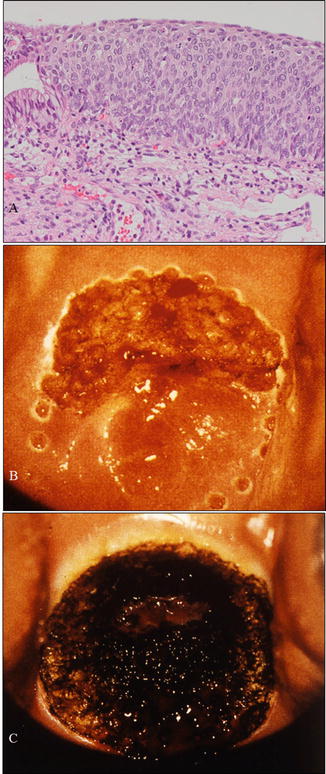

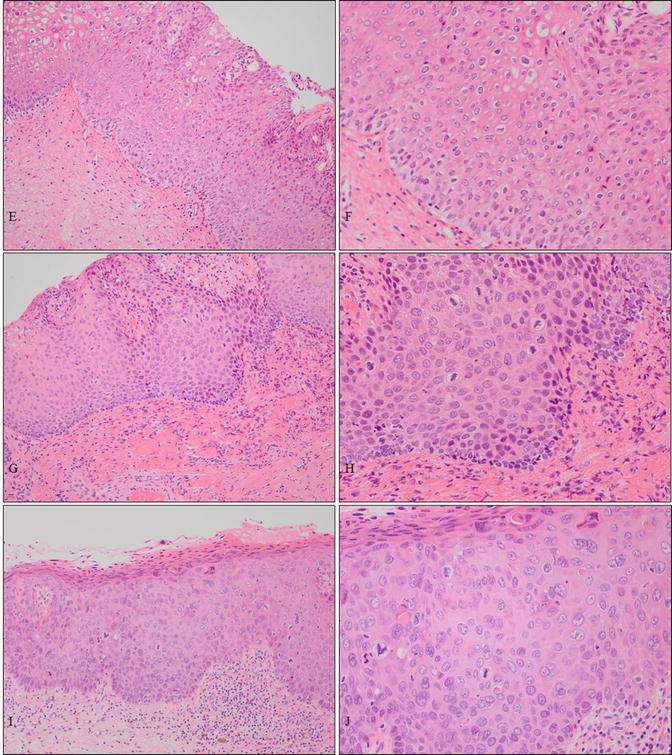

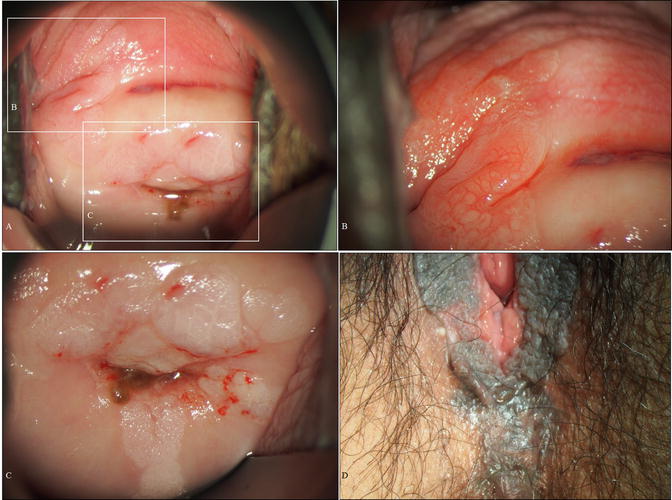

Fig. 14.5

A case of vaginal HSIL accompanied by other multifocal lesions of the lower genital tract. (a–d) Colposcopic and gross findings of lower genital neoplastic syndrome. The patient was a 43-year-old woman, nulligravida, who had been receiving immunosuppressive therapy for myasthenia gravis. Multiple lesions involving the upper third of the vagina (a, b), other uterine cervical sites (c), the vulva (d), the perineum, and the anus. (e–j) Microphotography of the biopsies demonstrating cervical HSIL (e, f), vaginal HSIL (g, h), and vulvar HSIL (i, j) (e–j: hematoxylin-eosin staining, magnification ×10 for e, g, i and ×20 for f, h, j)

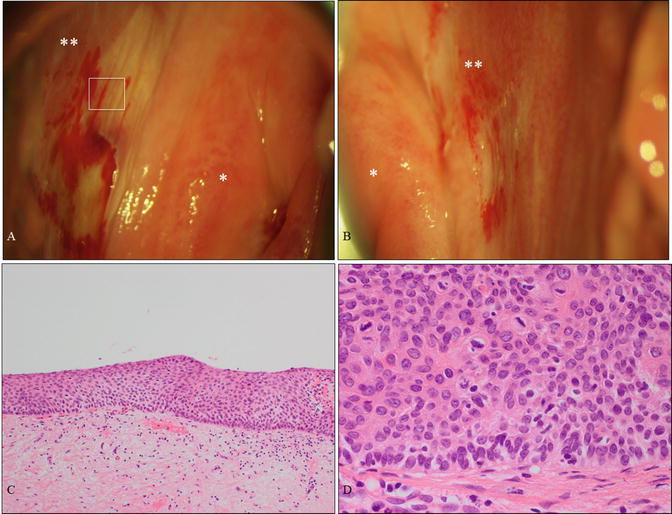

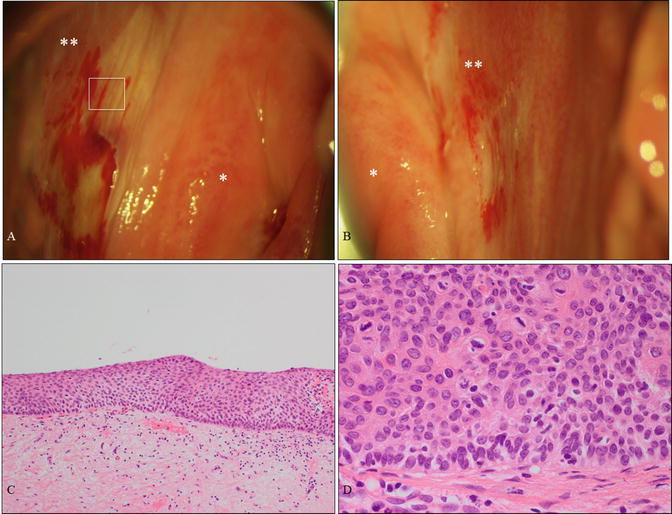

Fig. 14.6

A case of vaginal HSIL alone affecting the vaginal fornix. (a, b) Colposcopic findings at the right fornix (a) and left fornix (b) revealing mild acetowhite lesions. The patient was a 61-year-old woman without cervical or vulvar lesions and no previous history of HPV-related disease. (c, d) Microphotography demonstrating HSIL (c, d: hematoxylin-eosin staining, magnification ×4 for c and ×40 for d) . * uterine cervix; ** vaginal fornix

Evidence regarding the optimal clinical management of HSIL is lacking. Empirical practices include surgical excision or ablation of suspicious areas [68, 69]. Conservative surveillance in selected populations has been reported previously; however, the efficacy and safety of these approaches is not well known [65]. Renavelu et al. suggested the following limitations frequently apply to HSIL studies: (a) clear definitions of “remission” and “recurrence” are lacking; (b) the majority of case series are smaller; (c) those of comparable size date back 10 years; (d) previous papers report a mixed series of LSIL and HSIL; and of particular note, (e) the role of abnormal cytology as a preclinical indicator of disease recurrence has not previously been established among women posttreatment [65].

Clinical Treatments (Fig. 14.7)

Fig. 14.7

Overview of clinical management for vaginal precancerous lesions. WHO World Health Organization, SIL squamous intraepithelial lesion, VAIN1 vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1, VAIN2 vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2, VAIN3 vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3, LSIL low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, HSIL high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

There is no general consensus regarding the optimal treatment for vaginal HSIL. However, HSIL can be successfully treated by either excision or laser vaporization with reported success rates ranging from 69 % to 79 % for both treatments [66, 70, 71]. The major advantage of laser vaporization therapy is the ability to precisely control the depth and width of destruction through direct vision provided by colposcopy [72]. Although cancer progression rates for vaginal HSIL appears to be less than those of cervical HSIL, studies of patients with long-term follow-up after excision or laser vaporization reported subsequent vaginal carcinoma development in approximately 5 % of HSIL patients [61, 66, 71, 73].

Excisional Methods

Local excision is the main therapeutic approach for vaginal HSIL. Ideally, local excision of a small and isolated area is performed under local anesthesia. Excision of large or multiple areas can be performed under general anesthesia. When lesions involve the upper area or vaginal vault following hysterectomy, upper colpectomy may be appropriate. Alternatively, total colpectomy followed by vaginal restoration with a split-thickness skin graft may be considered. However, major surgery carries a risk of bladder and/or bowel fistula formation or shortening and narrowing of the vagina. Therefore, aggressive surgical procedures are considered inappropriate for the treatment of HSIL.

Ablative Methods

CO2 laser vaporization is an efficient treatment of histologically proven lesions with the absence of invasive carcinoma confirmed cytologically and colposcopically that may performed under local or general anesthesia [71]. Prior to vaporization, the lesion is injected with mixture of saline and anesthetic or saline alone that acts as a necessary protective buffer that prevents penetration to deeper tissues. Vaginal HSIL can be effectively treated by CO2 laser vaporization to a depth of 1.5 mm, sufficient for the destruction of epithelium containing vaginal SIL without damaging surrounding structures [71, 72]. Cavitational ultrasonic surgical aspiration (CUSA) may be effective and safe for the treatment of VAIN. CUSA allows selective removal of diseased tissue with minimal damage to surrounding healthy tissue [74, 75].

Other Treatments

Topical application of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) cream has been advocated by a varying proportion of investigators over the last three decades and was most frequently employed in the 1980s [61]. Vaginal burning with ulceration and vaginal bleeding, occasionally requiring surgery, are common complications of topical 5-FU administration. Combination therapy consisting of laser vaporization and 5-FU treatment may be preferred for the treatment of multifocal lesions, particularly in post-hysterectomy cases with deep vaginal angles [76]. Different treatment schedules and dose levels have been investigated to identify regimens that maintain efficacy while decreasing adverse effects. Some investigators have advocated surface irradiation as brachytherapy using an intravaginal applicator [77–79]. However, brachytherapy is associated with risk of recurrence and marked vaginal stenosis, increasing the difficulty of subsequent therapies [61]. A recent cohort study reported high rates of regression and cure of vaginal HSIL in patients treated with intravaginal estrogen alone or in combination with other treatment modalities. This treatment may represent a viable alternative therapy [80].

Clinical Management of the Vulvar Precancerous Lesions

Precancerous Lesions of the Vulva in This Chapter

1.

High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL). Synonyms: vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (VIN2) and grade 3 (VIN3), usual-type vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (uVIN)

2.

Differentiated-type vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN). Synonyms: carcinoma in situ of simplex type

Clinical Management

Management of Patients with Vulvar High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion

The incidence of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is increasing in women under 50 years of age [81]. The rising prevalence of human papillomavirus infection (HPV) has led to a continuously increasing incidence of VIN and vulvar carcinoma [82–84]. In 1986, the International Society for the Study of Vulvar Disease (ISSVD) introduced the term, VIN , to designate precursors of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Although VIN was initially considered a single category, strong evidence has subsequently accumulated over the last two decades indicating the existence of at least two distinct clinicopathologic subtypes, one associated with high-risk HPV infection and a second independent of HPV infection. In 2004, the ISSVD proposed a classification system reflecting these two subtypes: HPV-associated usual VIN (uVIN) and HPV-independent differentiated VIN (dVIN) . Following this proposal, dVIN is considered a clinical distinct entity from uVIN. The natural history of uVIN is thought to be similar to that of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) with high-grade uVIN considered a precancerous lesion [85]. The three-tier classification system has previously been used in the clinical management of VIN, but there has been renewed interest in the use of the two-tiered squamous epithelial lesion stratification system describing low-grade SIL (LSIL) and high-grade SIL (HSIL), nomenclature that more accurately reflects the similar natural history of uVIN to other lower anogenital tract HPV-associated intraepithelial lesions. The two-tiered squamous epithelial lesion stratification system for uVIN and use of the term dVIN were recently adopted in the newly released 2014 WHO classifications [86].

Vulvar HSIL has a diverse clinical presentation. Nonspecific symptoms , including pruritus, irritation, and pain, are observed in approximately 60 % of cases. In younger patients, symptoms are often preceded or accompanied by condylomas. Since patients commonly present asymptotically or with nonspecific symptoms, accurate vulvar inspection during routine gynecologic examination is important. Vulvar lesions may be red, white, or pigmented in color and either flat or raised and may coexist with erosions or ulcers [85, 87, 88]. These findings should prompt further vulvar examination using a magnification instrument such as a colposcope. The use of acetic acid is not recommended as it is nonspecific for vulvar HSIL [89]. Biopsy of the most suspicious part of the lesion should be performed under local anesthesia to confirm diagnosis. The diagnosis of vulvar HSIL is made from the clinical appearance and subsequent biopsy findings. Unifocal lesions are most commonly observed around the vaginal introitus. Perianal skin is involved in 10–15 % of the patients with vulvar HSIL [89].

The considerable temporal difference of 20–30 years between the peak incidence of vulvar HSIL and invasive vulvar carcinoma suggests that there may not always be a causal link between these two conditions [90, 91]. The risk of progression to invasive carcinoma in vulvar HSIL is considered to be low [88, 92, 93]. Further, vulvar HSIL is commonly multifocal, whereas invasive vulvar carcinoma is most frequently unifocal. The behavior of vulvar HSIL is not apparently comparable to that of cervical HSIL. Spontaneously regressing vulvar HSIL, so-called bowenoid papulosis [94], characterized by small, multifocal, papular, and hyperpigmented lesions affecting the labia majora and/or perianal skin is known to occur in younger women (Fig. 14.8). The high rate of regression has been reported in patients under 30 years and has been shown to be particularly common in pregnant women [92, 95].

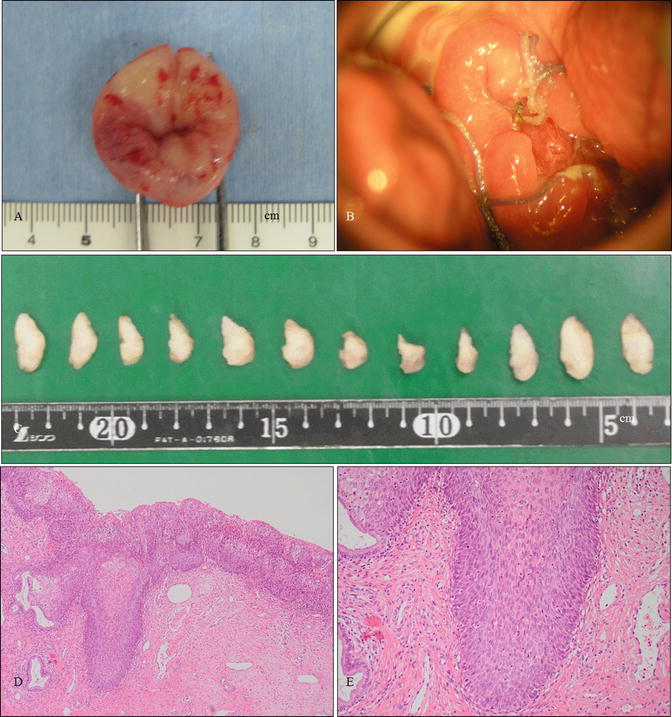

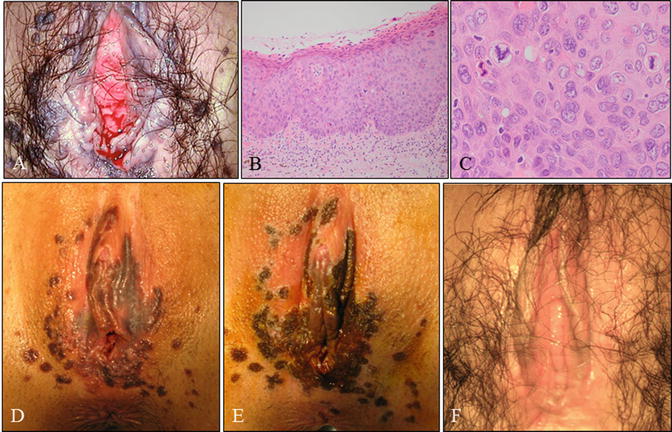

Fig. 14.8

Case of a young woman with vulvar HSIL, the so-called bowenoid papulosis . (a) Gross vulvar findings demonstrating multiple lesions. This is the same patient as shown in Fig. 14.3. The patient was a 25-year-old woman, nulligravida, with a 2-year history of cervical (Fig. 14.3) and vulvar HSIL referred to our hospital. (b, c) Microscopy of lesions demonstrating vulvar HSIL. (d, e) Pre- (d) and post- (e) laser therapeutic findings demonstrating pigmented and papular lesions ablated by laser vaporization. (F) Gross findings 2 months following laser vaporization and imiquimod therapy (b, c: hematoxylin-eosin staining, magnification ×10 for b and ×40 for c)

Management of Patients with Differentiated-Type Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia

Despite the fact that dVIN was first described in the 1960s by Abell as a highly differentiated form of vulvar carcinoma in situ, until more recently, the pathological entity had not gained wide attention because its existence had clinically been questioned [96, 97]. Recent knowledge has revealed that dVIN is often observed in areas of lichen sclerosus in older women [97, 98]. It is estimated that dVIN accounts for a small proportion with up to 5 % of all VIN lesions compared with uVIN [99, 100]. White or red lesions in areas of hyperkeratosis, ulceration, and the presence of a rough and irregular surface are all suspicious for dVIN (Fig. 14.9). Patients are often symptomatic with a long history of lichen sclerosus of vulvar itching and/or burning, and dVIN diagnosis might be frequently missed. Due to the highly malignant potential of dVIN, non-healing ulcers and/or newly developed white hyperkeratotic lesions in patients with lichen sclerosus should be periodically biopsied or excised without delay to obtain a representative histopathological diagnosis [91]. It should be emphasized that the recognition of dVIN in patients with lichen sclerosus can be extremely challenging owing to associated ulceration and fissuring [85].

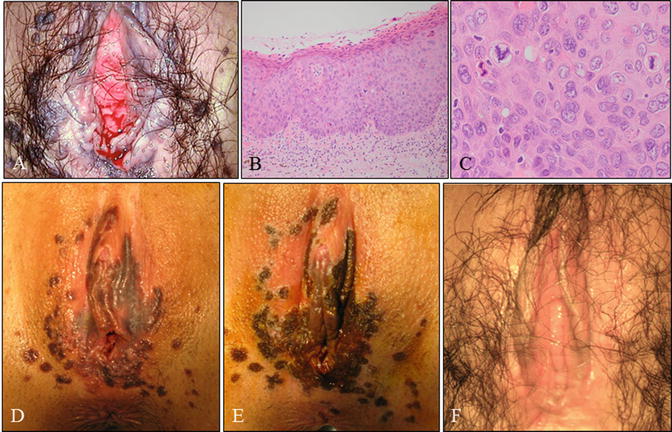

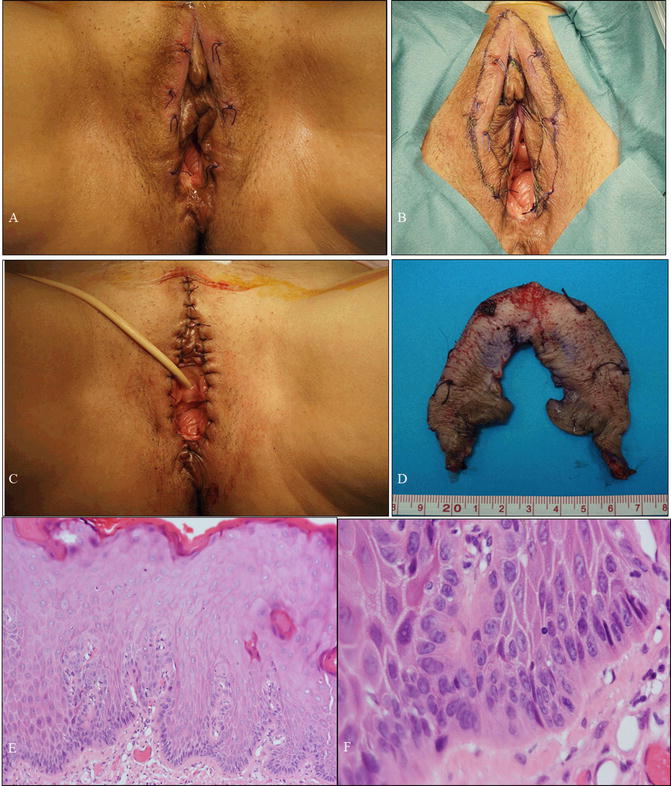

Fig. 14.9

A case of differentiated VIN (dVIN) . (a–c) Gross photography of the vulva at first presentation at our hospital (a), preoperatively (b), and postoperatively (c). The patient was a 60-year-old woman, gravidity 1, parity 1, with leukoplakia. Her complaint was severe itch sensation of her vulva. Vulvar biopsies indicated VIN, and high-risk HPV test of the vulvar skin was negative. (d) Macroscopic image of specimen obtained from simple vulvectomy preserving clitoris. (e, f) Microscopic findings demonstrating dVIN (e, f: hematoxylin-eosin staining, magnification ×4 for e and ×40 for f)

Clinical Treatments (Fig. 14.10)

Fig. 14.10

Overview of clinical management for vulvar precancerous lesions. WHO World Health Organization, SIL squamous intraepithelial lesion, VIN1 vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1, VIN2 vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2, VIN3 vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3, LSIL low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, HSIL high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

Clinical treatment is indicated for vulvar HSIL and dVIN but not LSIL. There is a low risk of progression from HSIL to invasive carcinoma [91], and there have been many more case reports of spontaneous regression of vulvar HSIL in young women compared to cervical HSIL [95] [92]. Surgical treatment in young women is associated with a risk of psychosexual sequelae [101]. Careful observation or conservative treatment should be considered in young patients with vulvar HSIL confirmed by accurate and repeated biopsy. However, cases of vulvar HSIL where invasion cannot be ruled out should be treated by surgical excision (Fig. 14.11). Surgical treatment should be performed in older women due to the highly malignant potential of dVIN. Choice of therapy depends on the extent of disease, the location of the lesions, and, importantly, the desires of the patient.

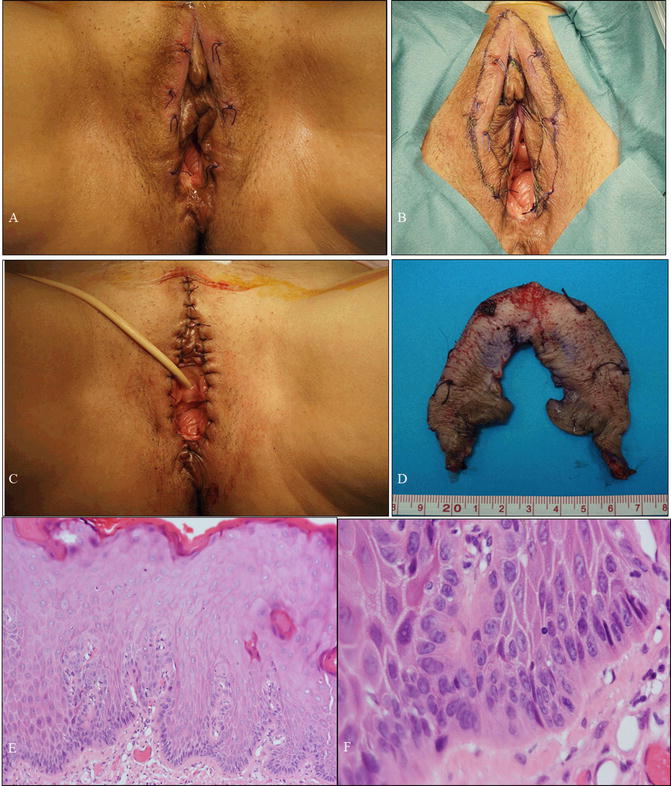

Fig. 14.11

Vulvar HSIL lesions with clinically suspected invasion. (a) Macroscopic findings of a vulvar lesion demonstrating four sites of biopsies (1–4). (b) A panel of microphotography of the biopsies (b: 1–4) indicating vulvar HSIL. The patient was a 39-year-old woman, nulligravida, with myelodysplastic syndrome with leukopenia. The patient had coexisting cervical HSIL. (c) Macroscopic findings following wide local excision and laser therapy. (d) Specimen obtained from wide local excision containing vulvar lesions clinically suspicious for invasion. (e, f) Histology indicating vulvar lesions were HSIL with invasive regions. The patient underwent radical vulvectomy with inguinal lymphadenectomy (b, e, f: hematoxylin-eosin staining, magnification ×4 for d and ×10 for b1–4, f)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree