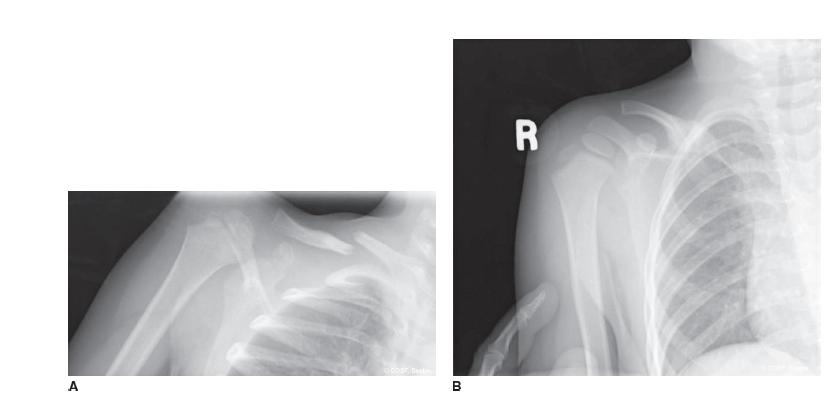

FIGURE 25-1Preoperative radiograph of segmental right clavicle fracture with pending skin compromise (arrow).

In an infant and young child, the differential diagnosis includes nontraumatic disorders such as infantile cortical hyperostosis, congenital pseudarthrosis (see Chapter 18), cleidocranial dysplasia, and short clavicle syndrome. In older children and adolescents, the differential includes neurofibromatosis and clavicular pseudarthrosis, Friedrich disease, hypertrophic osteitis, chronic multifocal periostitis and osteomyelitis, and SAPHO syndrome (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis).6

Pediatric and adolescent fractures are classified by location and fracture pattern. Simply, the fractures are (1) medial fractures and SCJ dislocations (see Chapter 24), (2) diaphyseal, and (3) lateral (distal) fractures and ACJ joint dislocations. The most common injury is in the middle third (75% to 85%) (sternocleidomastoid muscle insertion to coracoclavicular ligament insertion) followed by distal third (10% to 20%). The fractures can be subclassified as two-part, segmental, or comminuted; open or closed; and nondisplaced or displaced. The more complex the fracture pattern, the more risk of associated injuries, nonunion or malunion, and need for operative intervention.

Lateral or distal clavicle fracture dislocations at the ACJ in children and adolescents were classified by Dameron and Rockwood as a modification of the adult ACJ seindenttion classification system. Defining the injuries to the periosteum, acromioclavicular (AC), and coracoclavicular ligaments and assessing the direction of clavicular displacement determines the classification type. The coracoclavicular ligaments remain attached to the periosteum, and the clavicle bone remains intact but displaces out of the periosteal sleeve. Type I is nondisplaced; type II is a partial tear of the AC ligaments and lateral periosteum with some instability of the clavicle; in type III the clavicle is displaced superiorly (25% to 100% width of clavicle) with complete tear of AC ligaments and superolateral periosteum; with type IV the clavicle displaces posteriorly and gets entrapped in the trapezius muscle; type V is completely displaced (>100%) superiorly into the subcutaneous tissues; and type VI is displaced inferiorly beneath the coracoid. Distal clavicle fractures are further divided into nondisplaced or minimally displaced (type I); fractures medial to coracoclavicular ligament (type II); and intra-articular fractures (type III). Displaced intra-articular fractures are problematic.

More severe injuries can include a floating shoulder with damage to the clavicle and the scapula.7–9 This situation involves disruption of the superior shoulder suspensory complex and potentially an unstable shoulder girdle. Operative treatment of both fractures, one fracture, or neither has been advocated. Stabilization of unstable, displaced fractures is appropriate. Floating shoulder injuries are rare in children but should not be missed due to concern about associated injuries to the chest and intrathoracic organs. Similarly, there are reports of associated C1-C2 rotatory displacement with clavicle fractures. Finally pathologic fractures, such as postirradiation treatment, can occur and require a different and often more aggressive treatment protocol for successful healing.10

Surgical Indications

They want some clarity. We just don’t have answers for them.

—Ted Ludwig

The mainstay for treatment of midshaft and lateral clavicle fractures is immobilization and biologic healing in situ. Nonoperative treatment is indicated in the majority of middle and distal clavicle fractures. However, like many other pediatric and adolescent fractures, clavicle fracture treatment in the young, especially the athletic adolescent, is influenced by operative techniques and internal fixation outcomes in the adult.11–15

The indications for open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) of clavicle fractures in children are changing as we write. Clear indications for surgery include (1) open fractures, (2) displaced fractures with skin compromise (Figure 25-2) or neurovascular impairment, and (3), for most surgeons including us, type III, IV, and V lateral clavicle fracture dislocations. Evolving indications in many centers (including ours) for ORIF now include (1) displaced segmental and comminuted diaphyseal fractures in the adolescent (Figure 25-1), (2) polytrauma patients with displaced fractures, and (3) (less often) diaphyseal fractures with >2 cm of overlap in the older adolescent. The adult patients with the greatest initial fracture displacement had the most long-term complaints in terms of overhead strength and endurance.13,16,17 Polytrauma patients with displaced clavicle fractures had lower outcome scores.18 The risk of nonunion is higher when a lack of cortical contact and/or comminution exists between fracture fragments.19

All of the reasons noted above make ORIF of certain clavicular fractures in specific clinical situations and pediatric patients appropriate.

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Nonoperative Treatment

Nonoperative Treatment

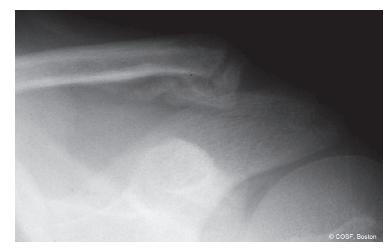

Nonoperative treatment of a nondisplaced or minimally displaced (<1 to 2 cm) fracture is indicated and will result in a 95% to 98% union rate and positive outcome20,21(Figure 25-3). Comindenttive results indicate that both a sling and a figure-of-eight dressing are equivalent. There is even some evidence that follow-up care is not necessary in these children, though we tend to follow them until full healing of bone and soft tissues is apparent.22

FIGURE 25-2 A: Tenting of the skin by a displaced, segmental diaphyseal clavicle fracture. This requires ORIF to prevent skin breakdown and an open wound. B: Closer inspection (circle) denotes the ischemic changes of the skin with blanching.

Radiographic healing occurs over the course of 4 to 12 weeks depending on the fracture pattern, age, and overall health of the patient. Palpable callus is present early (7 to 14 days) and coincides with decreased pain and self-protection. Restoration of motion and strength occurs readily in these stable fractures. Protection against refracture (~2%) is important until there is full bony healing, motion, and strength.

Types I, II, and III lateral clavicle fractures can be treated closed. The torn periosteum will heal (Figure 25-4), and even the mild-to-moderate displaced fractures will remodel. There are times where a distal “double barrel” clavicle will appear before the old superior clavicle resorbs as the new inferior clavicle forms in the periosteal sleeve. This can even occur in type V clavicle fractures if the patient is young enough and the family and surgeon can wait long enough. As with diaphyseal fractures, short-term immobilization for up to 3 to 4 weeks is followed by restoration of motion and strength before return to full activities.

FIGURE 25-3 A: Moderately displaced fracture treated with sling immobilization. B: Healed fracture with radiographic evidence of palpable callus on clinical exam.

FIGURE 25-4 Lateral clavicle fragment, type II, with abundant periosteal healing. The displacement will remodel with time.

Of the displaced fractures treated nonoperatively, some will heal with a symptomatic malunion. There will be a palpable exostosis, and the patients will complain of pain with direct contact (backpacks, sporting equipment). There may be loss of endurance and strength with overhead activities. Surgical treatment is either by corrective osteotomy or by exostosis excision. For the patients in whom there is normal strength, motion, and endurance but pain with direct pressure, exostosis excision is indicated.23

A modified beach chair position is utilized with prepping and draping of the involved arm and entire shoulder girdle to the SCJ. An incision in the skin lines is made directly over the clavicular malunion. Dissection is carried down to the exostosis while identifying and protecting the cutaneous nerves as they cross the clavicle from superior to inferior. The nerves descend deep into the platysma layer and often course with more easily identified veins. Cutting these nerves will cause a symptomatic neuroma. Subperiosteal dissection is performed, and the exostosis is isolated. With a rongeur and osteotomes, the exostosis is excised and the bone contoured to smooth surfaces. Rasping of the bone may be necessary. Bone wax is applied, and the wound is closed in layers, including periosteum, platysma, subcutaneous, and skin layers. Since we are trading a symptomatic bump for a scar, the aesthetics of the closure matter. Sling protection and restriction of activities are utilized until the risk of refracture is minimal.

ORIF Displaced Diaphyseal Clavicle Fractures

ORIF Displaced Diaphyseal Clavicle Fractures

Plate and Screw Fixation

The will to win is important, but the will to prepare is vital.

—Joe Paterno

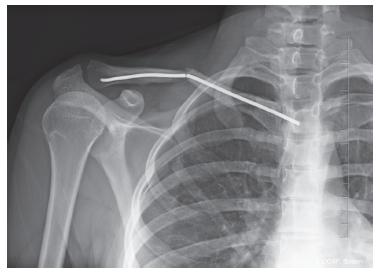

An ORIF approach to segmental, comminuted, open and markedly displaced fractures is more commonplace now than an orthopaedic generation ago. Fixation methods of diaphyseal fractures include plate and screws (locked and nonlocked, standard and precontoured),24–26 elastic nails,27–29intramedullary screws,30 threaded wires, and suture repair, among others. Although smooth wires have been used, concern about migration to areas of serious anatomic consideration makes most surgeons stay away from that technique. Although we use elastic nails for many pediatric fractures, we advocate for the use of plate and screw fixation with ORIF of operative clavicle fractures. We like to see and gently manipulate the segmental pieces into place while protecting the surrounding nerves, blood vessels, and vital organs. The fixation is stronger31 (Figure 25-5), and early rehabilitation is safer in our hands with stable plate and screw fixation. That does not mean that the other methods cannot work, as the evidence clearly shows they can. Healing and complication rates appear comindentble, though there is no prospective analysis for each method against each fracture type. Hardware irritation and removal rates and ease of extraction may differ among these methods.

FIGURE 25-5 Broken elastic nail placed at another institution as treatment for a diaphyseal clavicle fracture.

The options with plates include nonlocked versus locked; precontoured clavicle versus bending of standard double-stacked semitubular, dynamic compression, or pelvic reconstruction plates; and superior versus anterior-inferior plate placement. The advantages of anterior-inferior plates are theoretically a reduced risk of neurovascular injury with drilling and screw fixation and less of a likelihood of symptomatic hardware requiring implant removal. Superior plate position has better load to failure bending and torsional failure stiffness than anterior-inferior plates. Laterally, subperiosteal anterior plates may displace the periosteal attachment of the coracoclavicular ligaments. Locked plates are stiffer.32,33 Precontoured plates fit best on the medial 60% of the clavicle and fit adult men better than young people and women.34 Precontoured plates often lead to symptomatic hardware in young people, especially athletic women. The risk of refracture with clavicular implant removal leads us to a bias away from precontoured plates in many circumstances in adolescents unless the fit is perfect or the plate can be bent appropriately. Right now, we tend to bend standard plates (pelvic reconstruction most often) for best fit and place the plate superiorly.

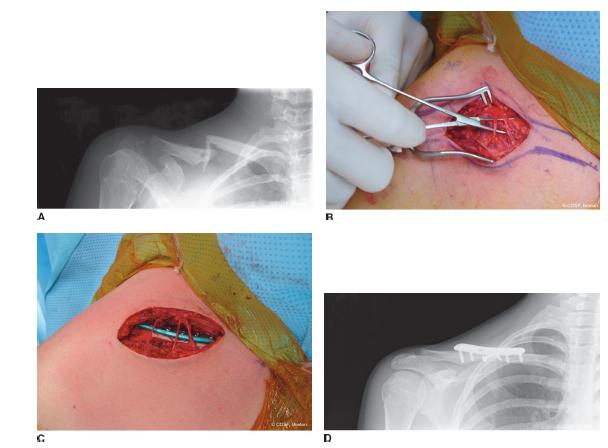

Surgery is carried out in a modified beach chair position. The entire shoulder girdle from opposite the SCJ through the ipsilateral arm is prepped and draped to allow for free arm movement during fracture reduction and fixation. Exposure is through an incision in the skin lines. The platysma, fascia, and periosteum are split in line with the clavicle. Care is taken to identify and protect the cutaneous nerves as they cross the clavicle to avoid a symptomatic neuroma (Figure 25-6B). Subperiosteal dissection of the clavicle is begun on either side of the fracture and carefully brought to the midline. Soft tissue attachments to malrotated, segmental fracture fragments are maintained. Vertical segmental pieces may project toward and/ or lie adjacent to the brachial plexus, subclavian vessels, and apex of the ipsilateral lung. These vertical fracture fragments often have an obvious or subtle coronal fracture line that increases the difficulty of fracture fixation. Careful dissection here is imperative. Fracture reduction is carried out while maintaining periosteal attachments to prevent devascularization of the bony fragments. Anatomic length and contour of the clavicle are restored. Temporary fixation with smooth wires may be necessary. The contoured (pre- or bent) plate is applied with proximal and distal screw fixation to maintain length and alignment. The plate chosen should fit the local anatomy (Figure 25-6C). Interfragmentary screw, or even suture, fixation of the segmental pieces is performed as necessary. Completion of screw fixation is performed while protecting the neighboring neurovascular structures with appropriate retractors and exposure. Rigid fixation is achieved with anatomic restoration of the clavicle. The periosteum, fascia, platysma, subcutaneous, and skin layers are closed. A simple dressing (Telfa and Tegaderm [Covidien, Mansfield, MA and 3M, St. Paul, MN, respectively]) is applied over the wound after local anesthesia injection. Either a sling or sling and swathe is used depending on the personality of the patient, fracture pattern, and fixation methods.

FIGURE 25-6 A: Preoperative segmental fracture. B: Operative exposure for ORIF clavicle fracture with isolation and preservation of the supraclavicular cutaneous nerves. C: ORIF of a displaced diaphyseal clavicle fracture with a precontoured clavicle plate. Note the preserved cutaneous nerves. D: Postoperative radiographs. Note the precontoured plate is not a perfect fit for this adolescent female. An interfragmentary compression screw was also used for stabilization of the segmental fracture fragment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Exostosis Excision

Exostosis Excision