Circadian Rhythm Disorders

Diagnosis and Treatment

Introduction

The emergence of a circadian rhythm disorder in a child may result from a genetic polymorphism,1 as a parent frequently suffers from the same symptoms or propensity. Parents perceive their child as sleep-deprived on school days. As a result, they allow the child to sleep as late as he or she wishes on weekends and holidays. Therefore, the child is unable to initiate sleep on Sunday night or awaken Monday for school.

Some Consequences of Circadian Rhythm Disorders

Circadian rhythm disorders’ major consequences are daytime sleepiness, inattention, combativeness, irritability, and hyperactivity. Children who are sleep-deprived secondary to delayed sleep phase disorder (DSPD) frequently have symptoms similar to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. DSPD may result in problems with school attendance and school performance. Some children with delayed sleep phase disorder may become school dropouts. A study of adolescents found that those with a tendency towards phase delay have more sleep problems, more daytime sleepiness and more emotional difficulties than do those without morning or evening preference or those with a morning chronotype.2

Biological Clocks and Circadian Rhythms

All individuals possess inherent circadian rhythms greater or less than 24 hours, the vast majority longer than 24 hours (Figure 5-1). The Horne and Ostberg Morningness/Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ)3 is a widely used scale that measures an individual’s preference to engage in various activities at an early or late hour. It is used to define an individual’s chronotype, or ‘lark’ versus ‘owl’ preferences. Fourth-grade children are mostly morning chronotypes. By adolescence, the majority are evening chronotypes.4 Chronotype shifts from preference to a disorder when the individual cannot sleep or wake at desired hours and suffers consequential academic or work-related difficulties.

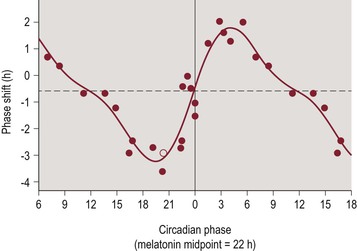

Figure 5-1 The PRC to the Bright Light Stimulus Using Melatonin Midpoints as the Circadian Phase Marker.

Phase advances (positive values) and delays (negative values) are plotted against the timing of the center of the light exposure relative to the melatonin midpoint on the pre-stimulus CR (defined to be 22 h), with the core body temperature minimum assumed to occur 2 h later at 0 h. Data points from circadian phases 6–18 are double plotted. The filled circles represent data from plasma melatonin, and the open circle represents data from salivary melatonin in subject 18K8 from whom blood samples were not acquired. The solid curve is a dual harmonic function fitted through all of the data points. The horizontal dashed line represents the anticipated 0.54 h average delay drift of the pacemaker between the pre- and post-stimulus phase assessments. (The figure legend is from the original text.) Sat Bir S Khalsa, SB, Jewett, ME, Cajochen, C and Czeisler, C, A phase response curve to single bright light pulses in human subjects, J Physiol June 15, 2003 vol. 549 no. 3 945–952.

Prevalence

Circadian rhythm disorders appear in approximately 10–18% of children and adolescents. Delayed sleep phase disorder alone effects up to 16% of adolescents but may appear in children as early as the start of school. It appears much less frequently in working adults. About 0.15% of adults, or 3 in 2000, have DSPD. Using the strict International Classification of Sleep Disorders diagnostic criteria, a random study in 1993 of 7700 adults (aged 18–67) in Norway estimated the prevalence of DSPD at 0.17%.5 Advanced sleep phase disorder children are seen much less frequently. This disorder also appears at the age of starting school. Before school age, waking at an early hour is normal. Normal infants and young children who wake at an early hour will nap during the day. Irregular sleep–wake disorder is extremely rare in children but typically emerges in adolescence. Non-24-hour circadian rhythm is relatively rare and appears in blind individuals, including children.

Delayed Sleep Phase Disorder

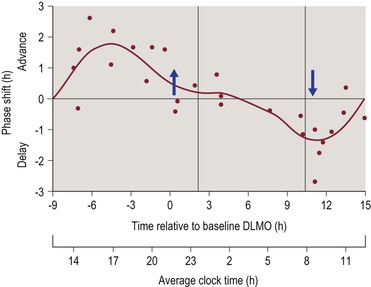

In DSPD, the major sleep episode is delayed by one or more hours of the desired bedtime, resulting in significant academic, work, or family issues. In general, children appear to be less tolerant of sleep deprivation than adults and an hour delay in sleep onset may result in pathological symptoms. DSPD is likely much more frequent than ASPD because the cycle length of the biological clock exceeds 24 hours in the overwhelming majority of individuals (Figure 5-2).

Figure 5-2 The Three Pulse Phase Response Curve (PRC) to 3 mg of Exogenous Melatonin Generated from Subjects Free-Running during an Ultradian LD Cycle.

Phase shifts of the DLMO are plotted against the time of administration of the melatonin pill relative to the baseline DLMO (top x-axis). The average baseline DLMO is represented by the upward arrow, the average baseline DLMOff by the downward arrow, and the average assigned baseline sleep times from before the laboratory sessions are enclosed by the vertical lines. Each dot represents the phase shift of an individual subject, calculated by subtracting the phase shift during the placebo session (free-run) from the phase shift during the melatonin session. The curved line illustrates the dual harmonic curve fit. The average clock time axis (bottom x-axis) corresponds to the average baseline sleep times. This PRC can be applied to people with different sleep schedules by moving the average clock time axis until the vertical lines align with the individual’s sleep schedule. (The figure legend is from the original text.) Burgess, HJ, Revel, VL, and Eastman, CI, A three pulse phase response curve to three milligrams of melatonin in humans, January 15, 2008 The Journal of Physiology, 586, 639–647.

Presenting Complaints

• Bedtime struggles or difficulty awakening at the desired time

• Complaint of insomnia at bedtime and/or excessive sleepiness in the morning

• Falling asleep at school or being too sleepy in the morning to participate in normal activities

• Symptoms consistent with behavioral hyperactivity, ADHD, or depression

• The child prefers not to eat breakfast and is hungry at or close to bedtime.

Diagnostic Criteria

• the sleep pattern is significantly delayed, typically by more than one hour,

• there is an inability to fall asleep at the desired clock time and an inability to awaken spontaneously at the desired time of awakening,

• this sleep pattern has been present for at least 1 month,

• normal quality and quantity sleep are observed when the child can sleep on his or her desired schedule,

• children with DSPD sleep later on weekends and holidays,

• they report less daytime sleepiness on weekends when they awaken spontaneously at a later hour,

• no other sleep or psychiatric disorder is present that could explain the patient’s symptoms,

• the delayed phase is not the result of social preference or an overloaded school, social activity, or work schedule.

Coexistence with Psychiatric/Behavioral Symptoms

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional symptoms, conduct disorder, aggressive symptoms, and symptoms of depression appear frequently in many but not all children with DSPD.6 In some instances, DSPD leads to chronic sleep deprivation which may aggravate underlying psychopathological tendencies in a child.7 When psychiatric symptoms and DSPD are present conjointly, it is important to establish if the psychiatric symptoms are present independent of the DSPD or only occur with it.8 For example, on weekends or holidays, when the child sleeps until spontaneous awakening, do psychiatric symptoms lessen? If the psychiatric symptoms and DSPD coexist temporarily, it is best to treat the DSPD before addressing the psychiatric symptoms. If the psychiatric symptoms are present regardless of prior sleep, it is best to treat both the psychiatric symptoms and the DSPD concurrently.

Evaluation

• usually have one parent with DSPD symptoms or ‘night owl’ preference,

• typically feel their best and best accomplish tasks such as homework at a later hour,

• ‘feel best’ at or near bedtime,

• encounter academic, emotional, and behavioral problems during morning hours,

• might require a urinary toxicology screen in some adolescents,

• in certain cases should be evaluated for depression, ADHD, school refusal, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and anxiety disorders,

• in some cases it is helpful for the family to maintain a diary of bedtime, time of sleep onset, and wake up time for a minimum of two weeks and as long as one month to establish a pattern,

• may give a significantly different description of their sleep habits then do their parents,

• tend to cover windows to black out sunlight,

• watch TV or are in front of computer monitors near or after their desired bedtime.

The Singular Significance of Sunday Night

Sunday night bedtime frequently is the major flash point for school-age children. Many children with DSPD awaken and retire at a considerably later hour on weekends, effectively ‘moving’ to a more westward time zone. This is also called social jet lag.9 Parents and child expect to return to a weekday schedule Sunday night (or move east) and the child finds it impossible.

Treatment of DSPD

Treatment of DSPD with Optimally Timed Light Exposure

There is a phase response curve to bright light (Figure 5-1) describing the amplitude or phase advance or delay when an individual is exposed to bright light at various times. Light advances or delays circadian rhythms in humans more than any other zeitgeber.

Light Switches from Causing a Phase Delay to Causing a Phase Advance during Sleep

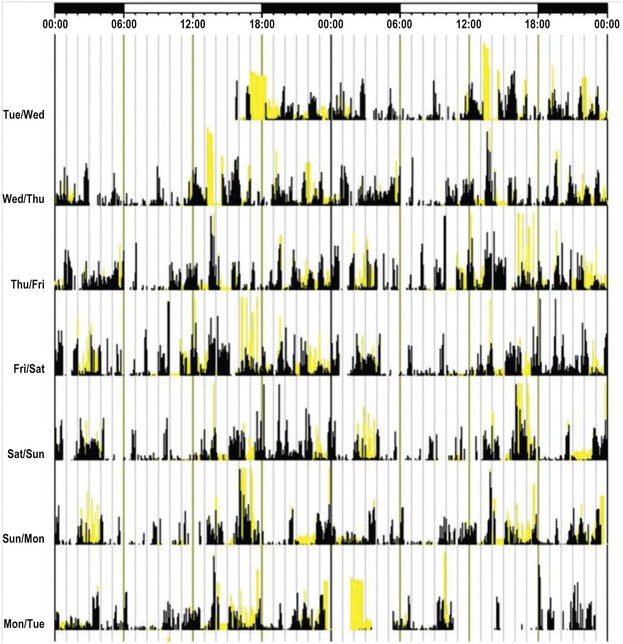

A child with DSPD who begins sleep at 3:00 a.m. on weekends and awakens at 1:00 p.m. will have a temperature minimum about 9–10:00 a.m. Light administered before the minimum causes a phase delay, or results in sleep occurring later, and light administered after the minimum causes a phase advance, or results in sleep occurring earlier (Figure 5-3).

Figure 5-3 Actogram obtained by actigraphy over a 7-day period from an older adult patient who has ISWRD. The yellow bars indicate timing and level of ambient light exposure, and the black bars indicate activity levels recorded at the non-dominant wrist. Note the lack of a discernible circadian sleep–wake rhythm. Sleep is characterized by nocturnal fragmentation and multiple short periods of sleeping and waking across the entire 24-hour day. (Legend from original text.) Zee PC, Vitiello MV. Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorder: Irregular Sleep Wake Rhythm Type. Sleep Med Clin. 2009 Jun 1;4(2):213–218.

Between the vernal and autumnal equinoxes, when day is longer than night, morning sunlight alone is extremely helpful in advancing phase. As soon as a child awakens, have him or her play in sunlight, preferably outdoors, but possibly indoors, in an area illuminated by sunlight. It also has a mood-elevating and antidepressant effect, as morning exposure to bright light boxes is a recognized treatment for seasonal affective disorder (SAD) and other mild depressive disorders.10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree