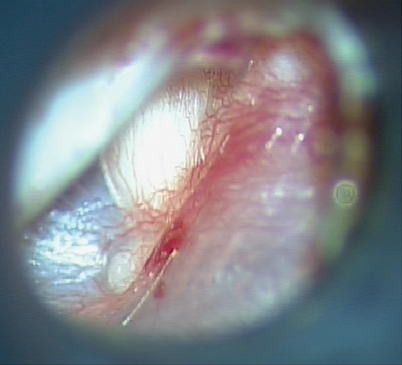

Fig. 12.1

Endoscopic view of the right ear with an attic cholesteatoma and pars tensa perforation. (Copyright held by Dennis S. Poe, MD, PhD, Boston Children’s Hospital)

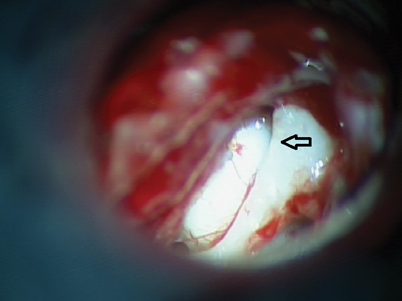

Fig. 12.2

Intraoperative microscopic view of the right ear with an attic (triangle) and mastoid (star) cholesteatoma. Posterior canal wall marked with an arrow. (Copyright held by Dennis S. Poe, MD, PhD, Boston Children’s Hospital)

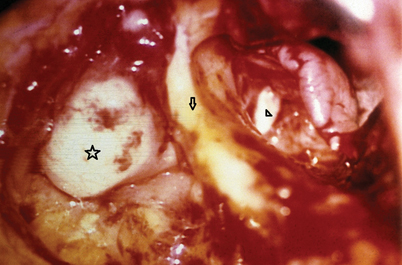

Fig. 12.3

Endoscopic view of the left ear with a posterior superior cholesteatoma and a pars flaccida retraction pocket. Malleus handle marked with a star. (Copyright held by Dennis S. Poe, MD, PhD, Boston Children’s Hospital)

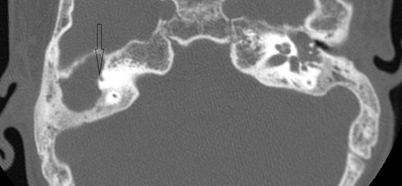

Fig. 12.4

Microscopic view of the left ear with a congenital cholesteatoma behind an intact tympanic membrane. (Copyright held by Dennis S. Poe, MD, PhD, Boston Children’s Hospital)

Fig. 12.5

Intraoperative microscopic view of the same (Fig. 12.4) left ear with a congenital cholesteatoma. Malleus marked with an arrow and cholesteatoma mass located anterior to malleus. (Copyright held by Dennis S. Poe, MD, PhD, Boston Children’s Hospital)

Pathophysiology

Eustachian tube dysfunction is probably the principal pathologic condition that leads to acquired cholesteatoma [2].

There are three different conditions in which squamous epithelium may gain access into the middle ear: (1) tympanic membrane retraction pocket, (2) migration or displacement of squamous epithelium into the middle ear through an acute or chronic perforation in the tympanic membrane, (3) iatrogenic, e.g., through ventilation tube or after middle ear operation [3].

The chronic inflammation associated with cholesteatoma induces squamous epithelial proliferation, migration, and bone resorption [1, 4].

A cholesteatoma is defined as congenital when there is a completely intact tympanic membrane without any evidence of retraction or perforation and there is an absence of any history of significant otitis media [5].

Molecular/Genetic Pathology

Osteoclast activity and thus bone resorption are increased because of chronic inflammation caused by cholesteatoma and presence of bacteria [6].

Proteolytic inflammatory cytokines (metalloproteinases, MMP2, MMP9) have been shown to be increased in pediatric cholesteatoma in comparison to adults [4].

Angiogenesis seen in the perimatrix of cholesteatoma is higher in pediatric than adult patients [4].

Incidence and Prevalence

Pediatric prevalence is about 3/100,000 compared to 9/100,000 in adults [7].

Age Distribution

Sex Predilection

Risk Factors—Environmental, Life Style

Presentation

Symptoms

The full spectrum of chronic middle ear infection symptoms may be seen in acquired cholesteatoma:

Foul smell otorrhea and hearing loss are the main symptoms in acquired pediatric cholesteatoma .

Facial weakness and vestibular symptoms are marks of more extensive disease.

Intracranial symptoms are a rarity.

A congenital cholesteatoma might not have any symptoms until it reaches a size that causes conductive hearing loss or it blocks the Eustachian tube to cause otitis media. Often, it is discovered as a white mass behind an intact tympanic membrane.

Patterns of Evolution

Most commonly, chronic retraction of the tympanic membrane results in a persistent pocket that becomes bound down by fibrous adhesion to the undersurface of the attic, superior tympanic ring, or the ossicles. This pocket may progressively enlarge and deepen or perforate, eventually generating or collecting squamous debris around the margins or within the pocket. The pocket may subsequently enlarge, erode bone, or become infected with progressive chronicity or local destruction.

The presentation of symptoms in acquired cholesteatoma is typically similar to those of chronic middle ear infection and it is often resistant to topical and systemic treatments, with otorrhea recurring promptly after repeated treatments.

Differential Diagnosis

Chronic middle ear infection, cholesterol cyst (granuloma).

Diagnosis and Evaluation

Physical Examination

Otomicroscopic examination may reveal a deep tympanic membrane retraction pocket, a tympanic membrane perforation with squamous epithelium migrating into the middle ear, granulation tissue, or polyps in the middle ear [2].

Retraction pockets are typically seen in the posterior superior part of the pars tensa or in the pars flaccida.

Hearing loss is typically conductive. Sensorineural hearing loss may be associated with more extensive, aggressive, or chronic disease.

Imaging Evaluation

Temporal bone CT or MRI should be considered preoperatively. CT is particularly helpful for evaluating the size and pneumatization of the mastoid cavity (which helps in planning the type of mastoidectomy), assessing the extent of the cholesteatoma, revealing complications (e.g., semicircular canal fistulas or tegmen dehiscence), and detecting anatomical variants [1]. Typical findings on CT would be middle ear or mastoid cavity opacification or rounded lesions with soft tissue or fluid density and bony erosion (Figs. 12.6 and 12.7).

Fig. 12.6

An axial CT image of the right ear with a cholesteatoma. Extensive erosion with typical scalloping of bone is seen in the right mastoid cavity in which there is also a fistula to the anterior limb of the superior semicircular canal (ampullated end marked with a black arrow). (Copyright held by Dennis S. Poe, MD, PhD, Boston Children’s Hospital)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree