Kerry Robinson, Alice J Armitage, Deborah Hodes

Child protection

Child abuse exists in all cultures across the world. In the twenty-first century there is increasing international recognition that child maltreatment needs to be a high priority, requiring active prevention and legislation enforced by governments. This stance has been enshrined in article 19 of the United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), which states that ‘all children have a right to protection from all forms of physical and mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect and maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse while in the care of parent(s), legal guardian(s) or another person who has the care of the child’.

Currently, 193 countries are party to the UNCRC and once a country has ratified the treaty they are bound to its terms by international law.

Maltreatment worldwide

Although there is international condemnation of child maltreatment, it remains a universal problem defined by culture and tradition. The lack of standardized data collection and variation in definitions of child maltreatment make worldwide comparisons difficult to draw. The UN Secretary General’s report on violence against children estimates that in 2002 almost 53,000 children were murdered worldwide. The report also highlights the lack of governance and funding in poverty-stricken, fragile countries that provide the setting for widespread and serious forms of abuse and exploitation. Hundreds of millions of children are subject to child labour, sexual exploitation, female genital mutilation (FGM), honour-based violence and trafficking. Other abuses include child soldiers, feticide, abandonment, begging and orphans who are often institutionalized. A global action plan will address the determinants of abuse, which include poverty, family violence, culture and tradition, institutional care, discipline, armed conflict and treatment of girls.

Maltreatment in England

In England, a series of high-profile child deaths have shaped attitudes and legislation around child protection. Nomenclature is different in the other three countries of the UK, but the underlying principles are the same. Two particular cases were the tragic deaths of Jasmine Beckford and Victoria Climbié. Jasmine Beckford’s death in 1984 shocked the nation and led to the Children Act of 1989. This established the principle that the welfare of the child (as opposed to the rights of the parents) is paramount in decisions made regarding their upbringing. Victoria Climbié’s death in 2000 resulted in the Children Act 2004, which augmented established legislation emphasizing the integration of local services based around the needs of the child.

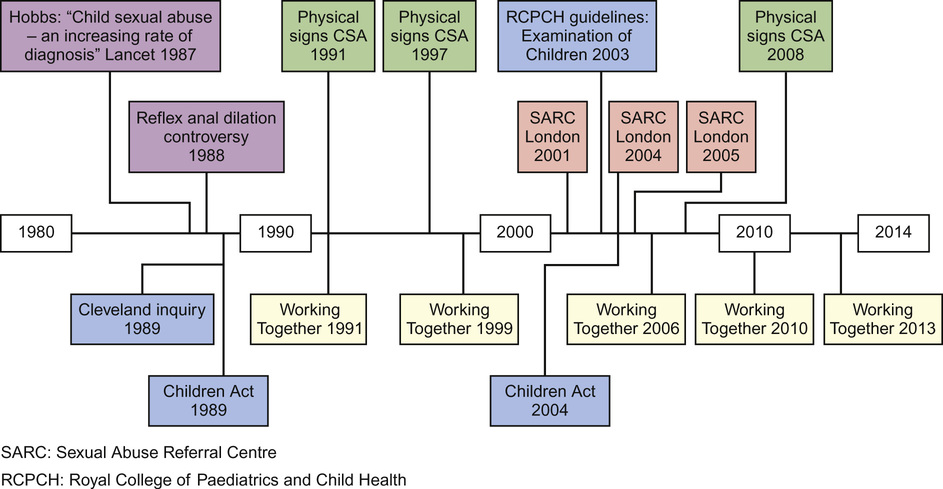

Since the inception of the first Children Act, there has been complex and frequently changing guidance published around child maltreatment, which is often challenging for the professionals involved (Fig. 8.1).

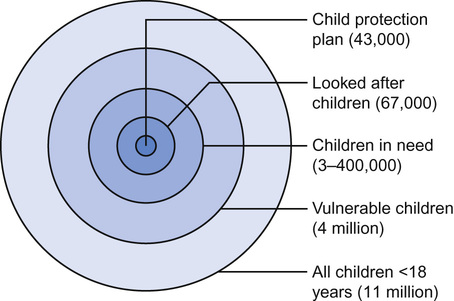

Of approximately 11 million children across the UK, professional efforts are directed towards those subject to a Child Protection Plan and ‘looked after children’. As shown in Figure 8.2, this represents only a small proportion of the ‘children in need’ and those defined as vulnerable, which includes disabled children and those living in poverty. Sadly, high-profile cases continue, with Peter Connelly in 2007 and Daniel Pelka in 2012 representing two of approximately 85 child deaths per year attributed to child maltreatment.

In child protection today, there is an emphasis on the importance of multi-agency information-sharing and communication along with early intervention. This is a change that has taken place over the last 30 years. According to the multi-agency document Working Together 2013, the approach to child protection should be underpinned by two key principles:

Why recognition and response is important

We all know that children may die from abuse. Less well recognized are the long-term sequelae in adulthood, that spare only the resilient minority. Outcomes include long-term health problems with poorer physical health, more risk taking, more medically unexplained symptoms and an increase in mental health problems including depression and suicide. Victims have lower educational attainment and difficulty parenting and thereby perpetuate the abusive cycle.

Sequelae have been shown to be both structural and functional. There is evidence from MRI studies that child maltreatment in the first two years of life, when brain growth is maximal, affects the developing brain. Persistent psychological maltreatment is a potent source of anxiety and stress, which disrupts the development of the neuroendocrine system. There is dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, and parasympathetic and catecholamine responses which persist, so that the child either continues with a heightened response to stress or dissociates and withdraws.

During the first two years, there is also both synaptogenesis and synaptic pruning prior to myelination of the brain pathways. Studies have also shown that severe maltreatment can lead to alterations in this process and an overall reduction in brain volume. So, there is now increasing evidence that abuse and neglect, particularly in early infancy, can be extremely harmful, resulting in damage to the development and function of the child’s brain, which later in life may lead to problems including aggression, depression, poor attention and concentration, social communication and relationship problems and anti-social behaviour. The importance of early intervention and attention to the chronicity of environmental adversity may indicate the need for permanent alternative caregivers, in order to preserve the development of the most vulnerable children.

The relatively new scientific field of epigenetics is also relevant to the cycle of child abuse and neglect. Its premise is that external influences can alter the way our DNA is expressed, and that this variability in expression is passed on in each generation.

Ever since the existence of genes was first suggested by Mendel in the 1860s and Watson and Crick described the double helix in 1953, science has developed the belief that DNA is nature’s blueprint. Chromosomes passed from parent to child form a detailed genetic design for development. Recent research revolutionizes this idea and suggests that genes can be altered. There are millions of markers on your DNA and on the proteins that sit on your DNA. These have been termed the epigenome (literally ‘upon genetics’). DNA itself might not be a static predetermined programme, but instead can be modified by these biological markers. Chief among them are methyl groups, which bind to a gene and say ‘ignore this bit’ or ‘exaggerate this part’.

Methylation is how the cell knows it needs to grow into, say, an eyeball rather than a toenail. There are also ‘histones’ controlling how tightly the DNA is spooled around its central thread and therefore how ‘readable’ the information is. And it is these two epigenetic controls – an on–off switch and a volume knob – which give each cell its orders.

Darwin’s central premise is that evolutionary change takes place over millions of years of natural selection, whereas this new model suggests characteristics are epigenetically ‘memorized’ and transmitted between individual generations.

Research on rats has identified changes in genes caused by the most basic psychological influence – maternal love. A 2004 study showed that the quality of a rat mother’s care significantly affects how her offspring behave in adulthood – rat pups that had been repeatedly groomed by their mothers during the first week of life were subsequently better at coping with stressful situations than pups who received little or no contact.

You might think this is nothing new; that we already know from Bowlby and Rutter’s work that a loving upbringing has positive psychological effects on children. But the epigenetic research suggests the changes are physiological as well as psychological. Epigeneticists also think socio-economic factors like poverty might ‘mark’ children’s genes to leave them more prone to drug addiction and depression in later life, regardless of whether they are still poor or not.

This all bears weight when considering the outcome for the future generations of children exposed to traumatic life events and fits in well with the intergenerational cycle of abuse that is well documented.

Prevalence and relationship with medical conditions

Surprisingly, maltreatment is more common than many other medical conditions (Table 8.1), but even these numbers are likely to be significant underestimates of the true prevalence. From interviewing adults, an NSPCC study found that 25% reported being subject to maltreatment in childhood. The changes in the number of children with a Child Protection Plan are shown in Table 8.2.

Table 8.1

Prevalence (per 10,000 children) of vulnerable children and medical conditions

| Child protection plan | 4.6 |

| Looked after children | 6 |

| Child in need | 64.6 |

| Cerebral palsy | 1.5–4 |

| Fetal alcohol syndrome | 2 |

| Severe learning disability | 3.7 |

| Sensorineural hearing loss | 1–2 |

| Down’s syndrome | 0.5 |

Table 8.2

Changes in the numbers of children on the child protection register (1999 and 2008) or with a Child Protection Plan (2013) in England and Wales

| Category of abuse | 1999 | 2008 | 2013 |

| Neglect | 13,400 | 13,400 | 17,930 |

| Physical abuse | 9,100 | 3,400 | 4,670 |

| Sexual abuse | 6,600 | 2,000 | 2,030 |

| Emotional abuse | 5,400 | 7,900 | 13,640 |

| Multiple | – | 2,500 | 4,870 |

| Total | 35,630* | 29,200 | 43,140 |

The relationship between medical conditions and abuse is complex. Recent studies found that as many as 30–60% of maltreated children will have a coexisting medical condition. Therefore, as many abused children will be seen either routinely or for a medical condition, it should be part of the differential diagnosis for any childhood presentation.

In summary, recognition and response to maltreatment is important to prevent the psychological and physiological changes at structural, functional and genetic levels. This may go some way to preventing poor outcomes for the child in question and also to stop the intergenerational cycle of abuse and neglect.

Why is recognition and response difficult?

Historically, child protection has been taught as a separate topic in paediatrics, but no such separation exists. Child maltreatment is a differential diagnosis for every medical condition discussed in this textbook. Protecting children requires thinking of the possibility of maltreatment in any child who presents and having it on the list of differential diagnoses. Serious case reviews highlight the failure to ‘think the unthinkable’ when professionals accept parents’ explanations too readily.

Although easy in theory, there are many barriers that prevent the professional from recognizing the possibility of abuse, including:

Risk, vulnerability and resilience

We know that there are factors that impact on the likelihood of abuse occurring, such as drug and alcohol misuse, psychiatric illness in the parents and domestic violence. However, none of them have a causal link and there will be families who provide excellent parenting despite very difficult circumstances. It is therefore helpful to consider the risks, vulnerability, and resilience factors in a non-judgemental fashion.

Risk

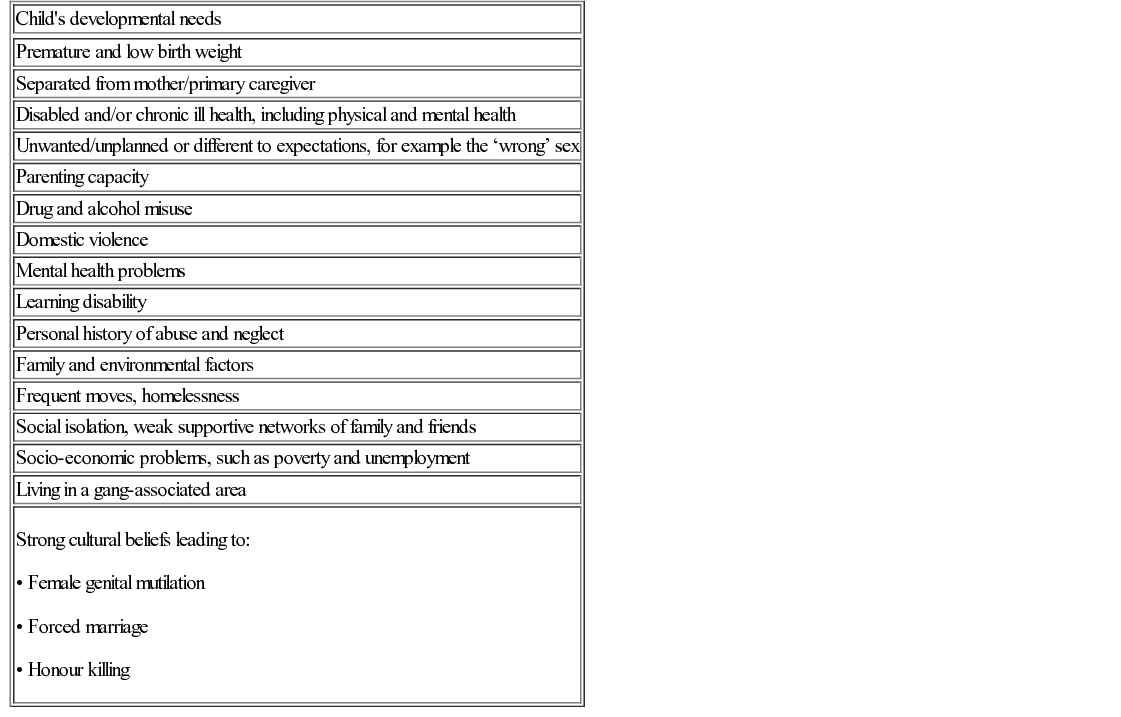

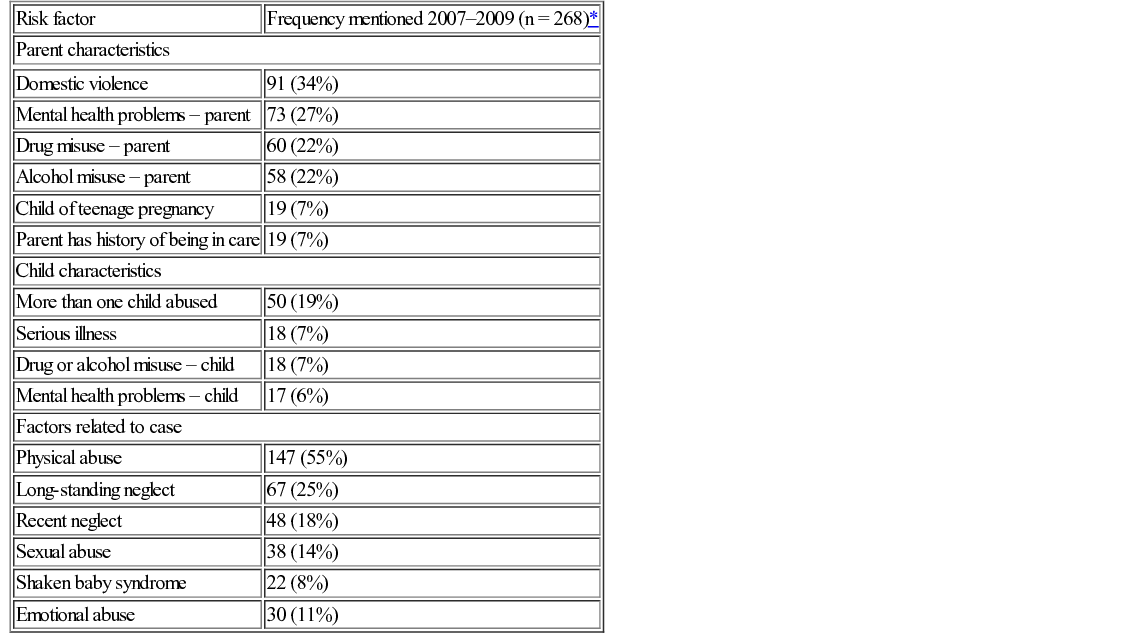

Using data from serious case reviews, risk factors identified in the child’s caregiving environment are shown in Table 8.3.

Table 8.3

Risk factors in serious case reviews

| Risk factor | Frequency mentioned 2007–2009 (n = 268)* |

| Parent characteristics | |

| Domestic violence | 91 (34%) |

| Mental health problems – parent | 73 (27%) |

| Drug misuse – parent | 60 (22%) |

| Alcohol misuse – parent | 58 (22%) |

| Child of teenage pregnancy | 19 (7%) |

| Parent has history of being in care | 19 (7%) |

| Child characteristics | |

| More than one child abused | 50 (19%) |

| Serious illness | 18 (7%) |

| Drug or alcohol misuse – child | 18 (7%) |

| Mental health problems – child | 17 (6%) |

| Factors related to case | |

| Physical abuse | 147 (55%) |

| Long-standing neglect | 67 (25%) |

| Recent neglect | 48 (18%) |

| Sexual abuse | 38 (14%) |

| Shaken baby syndrome | 22 (8%) |

| Emotional abuse | 30 (11%) |

Vulnerability

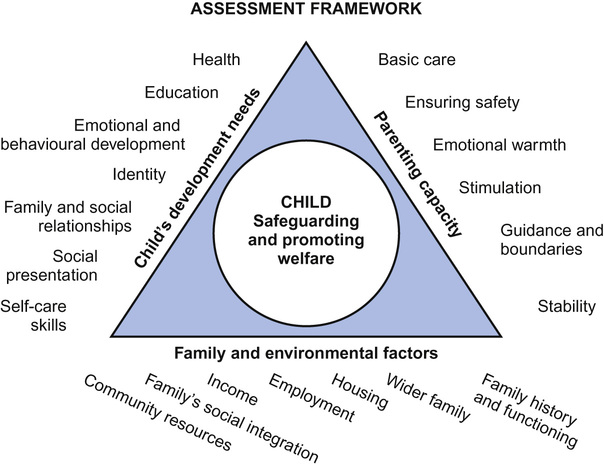

The common assessment framework (Fig. 8.3) is a tool used initially by social workers but now by all professionals, and forms the basis of the Common Assessment Framework (CAF) form used to make referrals to social care. It is a shared assessment and planning framework for use across all children’s services and all local areas in England. It aims to help the early identification of children and young people’s additional needs and promote coordinated service provision to meet them. By looking at the themes listed, vulnerability factors can be identified and a thorough medical history will usually elicit them. They are listed in Table 8.4.

Resilience

As well as factors that make children vulnerable to abuse, there are factors that are generally protective. A child may be resilient against abuse taking place, and when children are abused, some will have more resilience in terms of the outcomes. A strong relationship with a parent or significant other adult, an easy temperament and high cognitive ability are a few examples.

Practical guidance in the assessment of a child with suspicion or allegation of maltreatment

General approach

The child should be assessed in a rigorous and systematic way irrespective of whether there is an allegation of abuse, unexplained injury or the incidental discovery of abuse and/or neglect during any medical consultation. The only difference from the diagnostic process in any other disorder is that when maltreatment is diagnosed or suspected, the management occurs within a multi-agency context of assessment and planning for the child.

Timescales

All child protection assessments should be carried out within timescales appropriate to the type of abuse and the requirement for collection of evidential samples:

Consent

Consent should be sought from both child, where understanding allows, and the parent with parental responsibility (PR). If the child is brought without their parent, establish the reason. Request the parent to be present unless this would lead to distress for the child or a delay and loss of important acute signs. If there is no parent, then obtain consent from the person with parental responsibility; this maybe the local authority.

History-taking

Additional care should be taken in documenting time, place and people present during history-taking and examination, and record from whom you have taken a history. Talk to the child alone if there is no police interview (see ABE interview, below) and ask only open questions including those pertinent to the medical history and examination so that you can draw a conclusion regarding the presentation and allegation. The details of the story will be taken by the police in this situation. Asking leading questions prior to the ABE interview can lead to stories changing and important evidence being lost.

Use quotations and explicit descriptions when possible and distinguish between the history, observations, suspicions and interpretations. You should also consider risk factors and vulnerabilities for abuse (as listed above) in the history, remembering that cycles of abuse and neglect often repeat themselves through generations.

Documentation

Always document all findings fully, as any consultation may be subject to legal scrutiny; make clear, precise and contemporaneous notes; sign, date and print your name legibly under your signature. Use body maps whether the injury is accidental, non-accidental or uncertain, or draw diagrams. Comment on site, size, colour, cause of each lesion/injury as given by child and/or parent. Ensure you sign and date your body maps too. Include birthmarks and scars. Increasingly, there is a role for photography to supplement and be kept as part of the medical record. Consent must be obtained specifically for this.

Always conclude by linking the reason for the referral and the diagnosis you have made so that it is clear for social care and police.

It is important to establish whether the child has unmet health needs, such as outstanding immunizations, dental caries or chronic urinary tract infections, which could indicate medical neglect. Behavioural and emotional problems, including symptoms of post-traumatic stress, may be a consequence of maltreatment.

Examination

Conduct a thorough general physical examination to include height, weight and head circumference and plot them on a growth chart. Note the pubertal stage using the Tanner classification. Examine the whole body, including hair, nails, mouth, teeth, ears, nose, head, skin and hidden areas behind ears and neck.

Evaluate demeanour, response to carer, play, attention and behaviour during the time you spend with the child. Record whether or not the child was able to cooperate. If the examination is incomplete, explain how and why. Comment on developmental milestones, cognitive ability and school attainment (and attendance), all of which can be relevant to the diagnosis.

With the child’s permission, it is important to examine the buttocks and genitalia of all children whether or not there is a suspicion of sexual abuse; it is thought that in 1 in 7 physically abused children there is associated sexual abuse. Ensure the child or young person has a clear explanation of the process; that they understand that it is only doctors, with their and their parent’s permission, who can look, and this is part of starting to teach ‘keeping safe’.

Initially view the buttocks, anus and external genitalia. In boys, look for injury to the urethra, penis and scrotum, comment on the testes and presence of circumcision. In girls, look for any injuries to the external genitalia (including FGM) and note any vaginal discharge. Examine the anus and surrounding area for any injury, including lacerations (previously termed fissures) or scars.

If sexual abuse is suspected, a more detailed examination of the anogenital area with a colposcope should be undertaken by an expert (see below for more details).

Investigations

The need for medical investigations will be indicated by examination findings and any allegations. You will need to consult your local guidelines and the Child Protection Companion published by the RCPCH and available online. Some specifics are listed later in this chapter.

Diagnosis/opinion – coming to a conclusion

There are a range of diagnoses which may coexist:

• Clear medical diagnosis – lesion not the result of inflicted injury, for example Mongolian blue spot

• Newly identified health needs – may need follow-up/referral for ongoing assessment and management

Give an opinion on whether the findings are consistent with the allegation/history given. If there is uncertainty and/or no diagnosis, say so and outline the next steps, i.e. investigations, further referrals, etc.

Comment on other findings from history and examination, such as growth or language development, medical co-morbidities or unmet medical needs.

For clarity, use bullet points when listing the other factors elicited in history contributing to maltreatment, for example:

Management and communication

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree