Figure 3–1. Percentile standards for length for age and weight for age in girls, birth to age 36 months. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 1, 2009. Source: WHO Child Growth Standards—http://www.who.int/childgrowth/en.)

Figure 3–1. Percentile standards for length for age and weight for age in girls, birth to age 36 months. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 1, 2009. Source: WHO Child Growth Standards—http://www.who.int/childgrowth/en.)

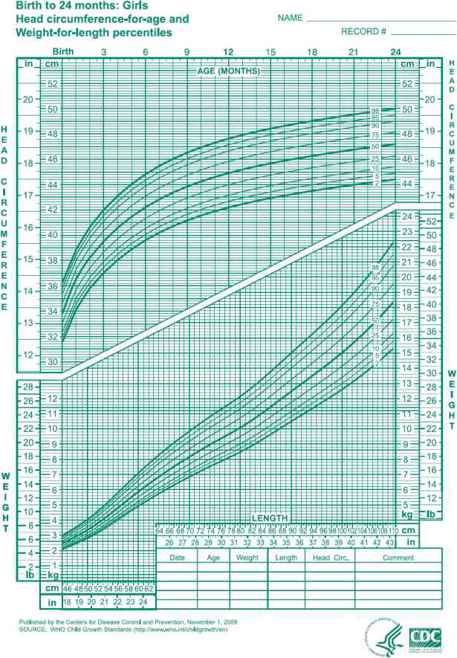

Figure 3–2. Percentile standards for head circumference for age and weight for length in girls, birth to age 36 months. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 1, 2009. Source: WHO Child Growth Standards—http://www.who.int/childgrowth/en.)

Figure 3–2. Percentile standards for head circumference for age and weight for length in girls, birth to age 36 months. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 1, 2009. Source: WHO Child Growth Standards—http://www.who.int/childgrowth/en.)

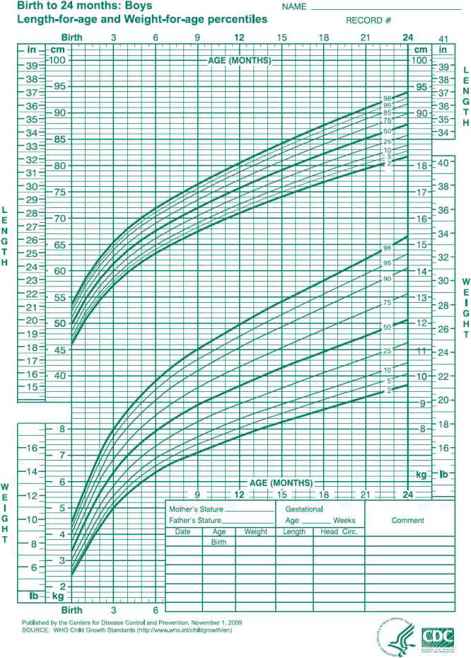

Figure 3–3. Percentile standards for length for age and weight for age in boys, birth to age 36 months. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 1, 2009. Source: WHO Child Growth Standards—http://www.who.int/childgrowth/en.)

Figure 3–3. Percentile standards for length for age and weight for age in boys, birth to age 36 months. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 1, 2009. Source: WHO Child Growth Standards—http://www.who.int/childgrowth/en.)

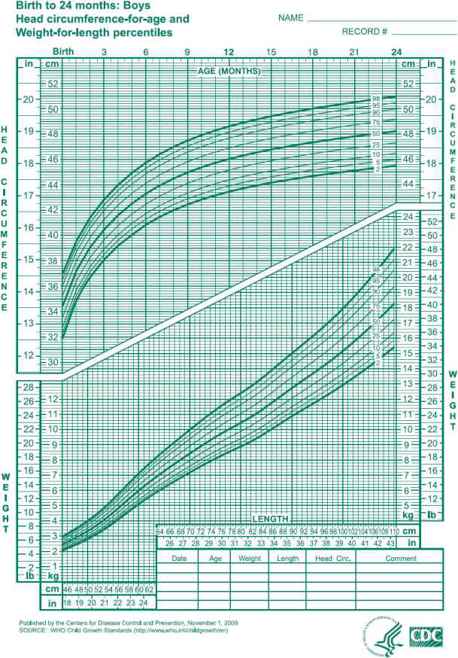

Figure 3–4. Percentile standards for head circumference for age and weight for length in boys, birth to age 36 months. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 1, 2009. Source: WHO Child Growth Standards—http://www.who.int/childgrowth/en.)

Figure 3–4. Percentile standards for head circumference for age and weight for length in boys, birth to age 36 months. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 1, 2009. Source: WHO Child Growth Standards—http://www.who.int/childgrowth/en.)

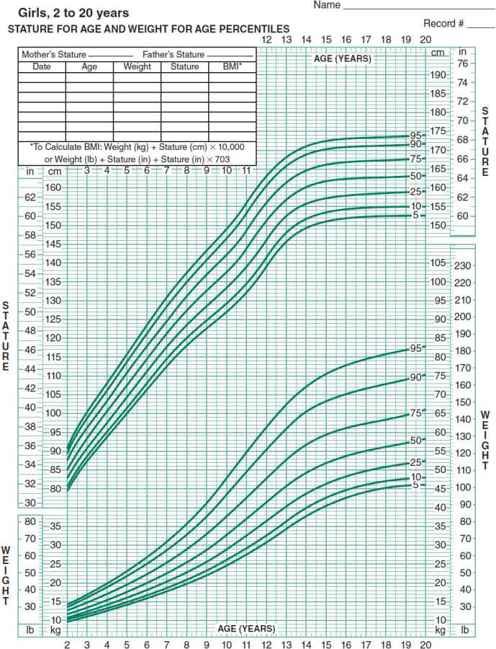

Figure 3–5. Percentile standards for stature for age and weight for age in girls, 2–20 years. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Figure 3–5. Percentile standards for stature for age and weight for age in girls, 2–20 years. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

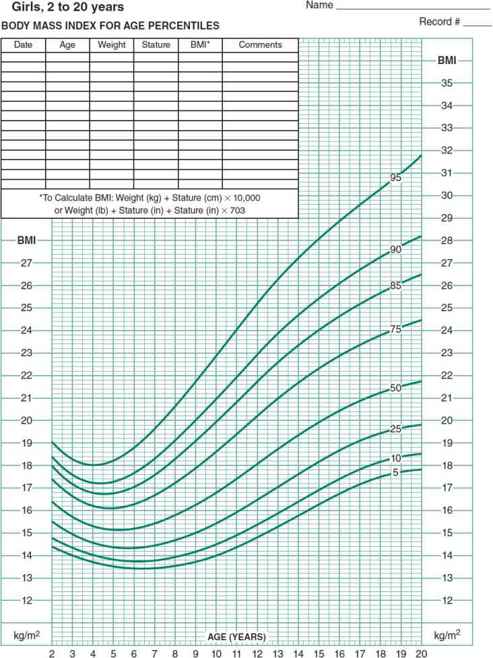

Figure 3–6. Percentile standards for body mass index for age in girls, 2–20 years. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Figure 3–6. Percentile standards for body mass index for age in girls, 2–20 years. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

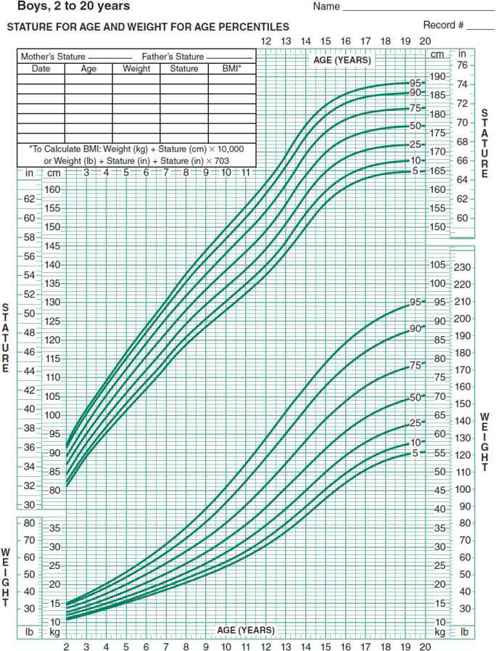

Figure 3–7. Percentile standards for stature for age and weight for age in boys, 2–20 years. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Figure 3–7. Percentile standards for stature for age and weight for age in boys, 2–20 years. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

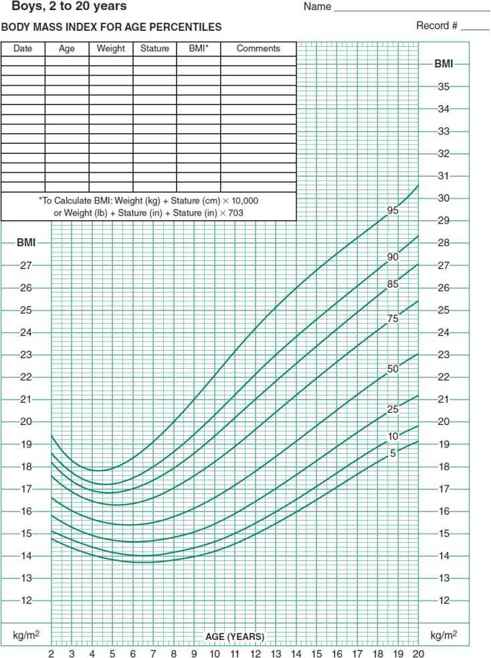

Figure 3–8. Percentile standards for body mass index for age in boys, 2–20 years. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Figure 3–8. Percentile standards for body mass index for age in boys, 2–20 years. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

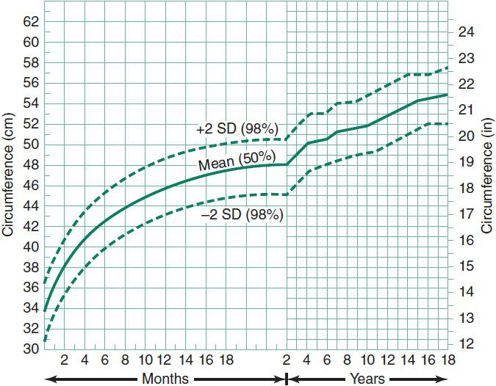

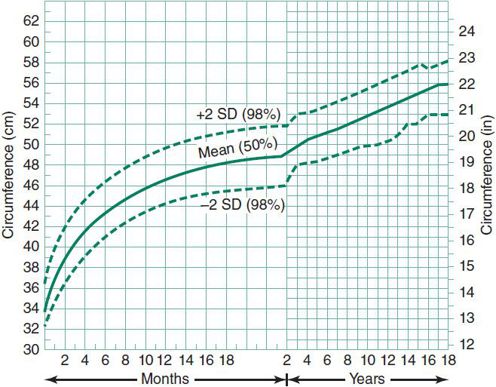

Figure 3–9. Head circumference of girls. (Modified and reproduced, with permission, from Nelhaus G: Head circumference from birth to eighteen years. Practical composite international and interracial graphs. Pediatrics 1968;41:106.)

Figure 3–9. Head circumference of girls. (Modified and reproduced, with permission, from Nelhaus G: Head circumference from birth to eighteen years. Practical composite international and interracial graphs. Pediatrics 1968;41:106.)

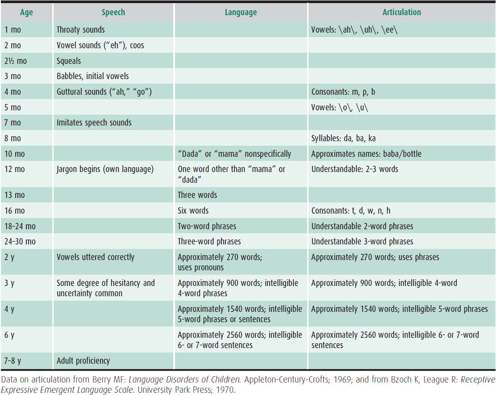

Figure 3–10. Head circumference of boys. (Modified and reproduced, with permission, from Nelhaus G: Head circumference from birth to eighteen years. Practical composite international and interracial graphs. Pediatrics 1968;41:106.)

Figure 3–10. Head circumference of boys. (Modified and reproduced, with permission, from Nelhaus G: Head circumference from birth to eighteen years. Practical composite international and interracial graphs. Pediatrics 1968;41:106.)

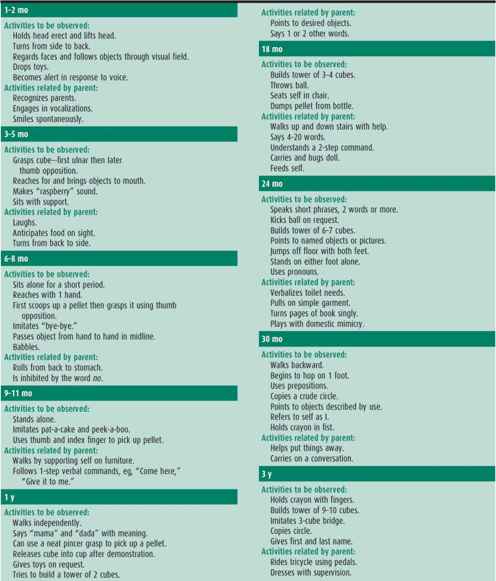

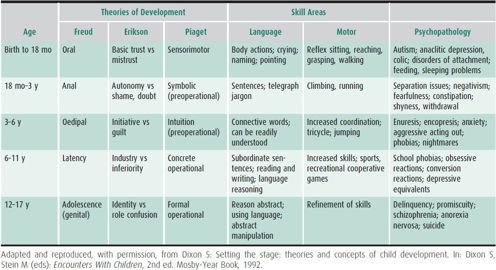

Table 3–1. Developmental charts.

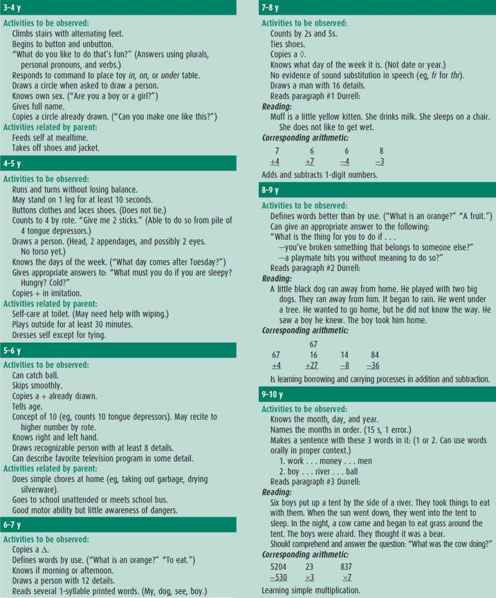

Table 3–2. Normal speech and language development.

Table 3–3. Perspectives of human behavior.

The first 5 years of life are a period of extraordinary physical growth and increasing complexity of function. The child triples his or her birth weight within the first year and achieves two-thirds of his or her adult brain size by age 2½–3 years of age. The child progresses from a totally dependent infant at birth to a mobile, verbal person who is able to express his or her needs and desires by age 2–3 years. In the ensuing 3 years the child further develops the capacity to interact with peers and adults, achieves considerable verbal and physical prowess, and becomes ready to enter the academic world of learning and socialization.

It is critical for the clinician to identify disturbances in development during these early years because there may be windows of time or sensitive periods when appropriate interventions may be instituted to effectively address developmental issues.

THE FIRST 2 YEARS

From a motor perspective, children develop in a cephalocaudal direction. They can lift their heads with good control at 3 months, sit independently at 6 months, crawl at 9 months, walk at 1 year, and run by 18 months. The child learning to walk has a wide-based gait at first. Next, he or she walks with legs closer together, the arms move medially, a heel-toe gait develops, and the arms swing symmetrically by 18–24 months.

Clinicians often focus on gross motor development, but an appreciation of fine motor development and dexterity, particularly the grasp, can be instructive not only in monitoring normal development but also in identifying deviations in development. The grasp begins as a raking motion involving the ulnar aspect of the hand at age 3–4 months. The thumb is added to this motion at about age 5 months as the focus of the movement shifts to the radial side of the hand. The thumb opposes the fingers for picking up objects just before age 7 months, and the neat pincer grasp emerges at about age 9 months. Most young children have symmetrical movements. Children should not have a significant hand preference before 1 year of age and typically develop handedness between 18 and 30 months.

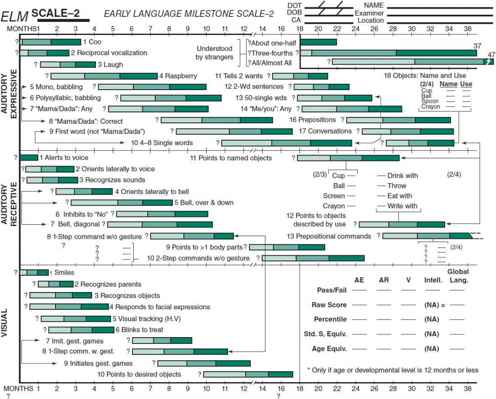

Language is a critical area to consider as well. Communication is important from birth (Figure 3–11, see Table 3–2), particularly the nonverbal, reciprocal interactions between infant and caregiver. By age 2 months, these interactions begin to include melodic vowel sounds called cooing and reciprocal vocal play between parent and child. Babbling, which adds consonants to vowels, begins by age 6–10 months, and the repetition of sounds such as “da-dada-da” is facilitated by the child’s increasing oral muscular control. Babbling reaches a peak at age 12 months. The child then moves into a stage of having needs met by using individual words to represent objects or actions. It is common at this age for children to express wants and needs by pointing to objects or using other gestures. Children usually have 5–10 comprehensible words by 12–18 months; by age 2 years they are putting 2–3 words into phrases, 50% of which their caregivers can understand (see Tables 3–1 and 3–2 and Figure 3–11). The acquisition of expressive vocabulary varies greatly between 12 and 24 months of age. As a group, males and children who are bilingual tend to develop expressive language more slowly during that time. It is important to note, however, that for each individual, milestones should still fall within the expected range. Gender and exposure to two languages should never be used as an excuse for failing to refer a child who has significant delay in the acquisition of speech and language for further evaluation. It is also important to note that most children are not truly bilingual. Most children have one primary language, and any other languages are secondary.

Figure 3–11. Early Language Milestone Scale-2. (Reproduced, with permission, from Coplan J: Early Language Milestone Scale. 2nd edition. Pro Ed, Austin, TX, 1993.)

Figure 3–11. Early Language Milestone Scale-2. (Reproduced, with permission, from Coplan J: Early Language Milestone Scale. 2nd edition. Pro Ed, Austin, TX, 1993.)

Receptive language usually develops more rapidly than expressive language. Word comprehension begins to increase at age 9 months, and by age 13 months the child’s receptive vocabulary may be as large as 20–100 words. After age 18 months, expressive and receptive vocabularies increase dramatically, and by the end of the second year there is typically a quantum leap in language development. The child begins to put together words and phrases, and begins to use language to represent a new world, the symbolic world. Children begin to put verbs into phrases and focus much of their language on describing their new abilities, for example, “I go out.” They begin to incorporate prepositions, such as “I” and “you” into speech and ask “why?” and “what?” questions more frequently. They also begin to appreciate time factors and to understand and use this concept in their speech (see Table 3–1).

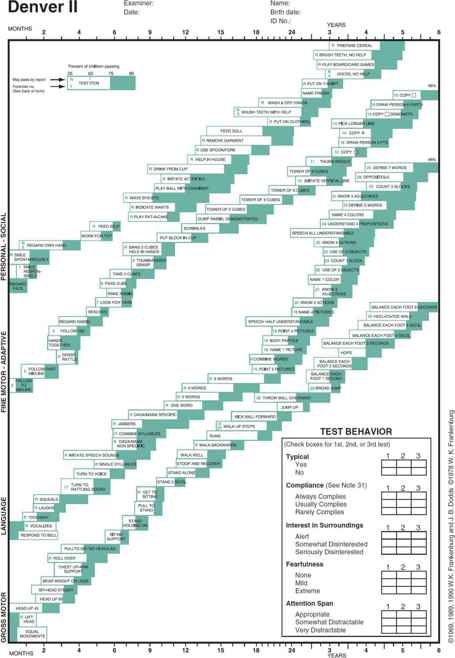

The Early Language Milestone Scale-2 (see Figure 3–11) is a simple tool for assessing early language development in the pediatric office setting. It is scored in the same way as the Denver II (Figure 3–12) but tests receptive and expressive language areas in greater depth.

Figure 3–12. Denver II. (Copyright © 1969, 1989, 1990 WK Frankenburg and JB Dodds. © 1978 WK Frankenberg.)

Figure 3–12. Denver II. (Copyright © 1969, 1989, 1990 WK Frankenburg and JB Dodds. © 1978 WK Frankenberg.)

One may easily memorize the developmental milestones that characterize the trajectory of the typical child; however, these milestones become more meaningful and clinically useful if placed in empirical and theoretical contexts. The work of Piaget and others is quite instructive and provides some insight into behavioral and affective development (see Table 3–3). Piaget described the first 2 years of life as the sensorimotor period, during which infants learn with increasing sophistication how to link sensory input from the environment with a motor response. Infants build on primitive reflex patterns of behavior (termed schemata; sucking is an example) and constantly incorporate or assimilate new experiences. The schemata evolve over time as infants accommodate new experiences and as new levels of cognitive ability unfold in an orderly sequence. Enhancement of neural networks through dendritic branching and pruning (apoptosis) occurs.

In the first year of life, the infant’s perception of reality revolves around itself and what it can see or touch. The infant follows the trajectory of an object through the field of vision, but before age 6 months the object ceases to exist once it leaves the infant’s field of vision. At age 9–12 months, the infant gradually develops the concept of object permanence, or the realization that objects exist even when not seen. The development of object permanence correlates with enhanced frontal activity on the electroencephalogram (EEG). The concept attaches first to the image of the mother or primary caregiver because of his or her emotional importance and is a critical part of attachment behavior (discussed later). In the second year, children extend their ability to manipulate objects by using instruments, first by imitation and later by trial and error.

Freud described the first year of life as the oral stage because so many of the infant’s needs are fulfilled by oral means. Nutrition is obtained through sucking on the breast or bottle, and self-soothing occurs through sucking on fingers or a pacifier. During this stage of symbiosis with the mother, the boundaries between mother and infant are blurred. The infant’s needs are totally met by the mother, and the mother has been described as manifesting “narcissistic possessiveness” of the infant. This is a very positive interaction in the bidirectional attachment process called bonding. The parents learn to be aware of and to interpret the infant’s cues, which reflect its needs. A more sensitive emotional interaction process develops that can be seen in the mirroring of facial expressions by the primary caregiver and infant and in their mutual engagement in cycles of attention and inattention, which further develop into social play. A parent who is depressed or cannot respond to the infant’s expressions and cues can have a profoundly adverse effect on the child’s future development. Erikson’s terms of basic trust versus mistrust are another way of describing the reciprocal interaction that characterizes this stage. Turn-taking games, which occur between ages 3 and 6 months, are a pleasure for both the parents and the infant and are an extension of mirroring behavior. They also represent an early form of imitative behavior, which is important in later social and cognitive development. More sophisticated games, such as peek-a-boo, occur at approximately age 9 months. The infant’s thrill at the reappearance of the face that vanished momentarily demonstrates the emerging understanding of object permanence. Age 8–9 months is also a critical time in the attachment process because this is when separation anxiety and stranger anxiety become marked. The infant at this stage is able to appreciate discrepant events that do not match previously known schemata. These new events cause uncertainty and subsequently fear and anxiety. The infant must be able to retrieve previous schemata and incorporate new information over an extended time. These abilities are developed by age 8 months and give rise to the fears that may subsequently develop: stranger anxiety and separation anxiety. In stranger anxiety, the infant analyzes the face of a stranger, detects the mismatch with previous schemata or what is familiar, and responds with fear or anxiety, leading to crying. In separation anxiety, the child perceives the difference between the primary caregiver’s presence and his or her absence by remembering the schema of the caregiver’s presence. Perceiving the inconsistency, the child first becomes uncertain and then anxious and fearful. This begins at age 8 months, reaches a peak at 15 months, and disappears by the end of 2 years in a relatively orderly progression as central nervous system (CNS) maturation facilitates the development of new skills. A parent can put the child’s understanding of object permanence to good use by placing a picture of the mother (or father) near the child or by leaving an object (eg, her sweater) where the child can see it during her absence. A visual substitute for the mother’s presence may comfort the child.

Once the child can walk independently, he or she can move away from the parent and explore the environment. Although the child uses the parent, usually the mother, as “home base,” returning to her frequently for reassurance, he or she has now taken a major step toward independence. This is the beginning of mastery over the environment and an emerging sense of self. The “terrible twos” and the frequent self-asserting use of “no” are the child’s attempt to develop a better idea of what is or might be under his or her control. The child is starting to assert his or her autonomy. Ego development during this time should be fostered but with appropriate limits. As children develop a sense of self, they begin to understand the feelings of others and develop empathy. They hug another child who is in perceived distress or become concerned when one is hurt. They begin to understand how another child feels when he or she is harmed, and this realization helps them to inhibit their own aggressive behavior. Children also begin to understand right and wrong and parental expectations. They recognize that they have done something “bad” and may signify that awareness by saying “uhoh” or with other expressions of distress. They also take pleasure in their accomplishments and become more aware of their bodies.

An area of child behavior that has often been overlooked is play. Play is the child’s work and a significant means of learning. Play is a very complex process whose purpose can include the practice and rehearsal of roles, skills, and relationships; a means of revisiting the past; a means of actively mastering a range of experiences; and a way to integrate the child’s life experiences. It involves emotional development (affect regulation and gender identification and roles), cognitive development (nonverbal and verbal function and executive functioning and creativity), and social/motor development (motor coordination, frustration tolerance, and social interactions such as turn taking). Of interest is that play has a developmental progression. The typical 6- to 12-month-old engages in the game of peek-a-boo, which is a form of social interaction. During the next year or so, although children engage in increasingly complex social interactions and imitation, their play is primarily solitary. However, they do begin to engage in symbolic play such as by drinking from a toy cup and then by giving a doll a drink from a toy cup. By age 2–3 years children begin to engage in parallel play (engaging in behaviors that are imitative). This form of play gradually evolves into more interactive or collaborative play by age 3–4 years and is also more thematic in nature. There are of course wide variations in the development of play, reflecting cultural, educational, and socioeconomic variables. Nevertheless, the development of play does follow a sequence that can be assessed and can be very informative in the evaluation of the child.

Brain maturation sets the stage for toilet training. After age 18 months, toddlers have the sensory capacity for awareness of a full rectum or bladder and are physically able to control bowel and urinary tract sphincters. They also take great pleasure in their accomplishments, particularly in appropriate elimination, if it is reinforced positively. Children must be given some control over when elimination occurs. If parents impose severe restrictions, the achievement of this developmental milestone can become a battle between parent and child. Freud termed this period the anal stage because the developmental issue of bowel control is the major task requiring mastery. It encompasses a more generalized theme of socialized behavior and overall body cleanliness, which is usually taught or imposed on the child at this age.

AGES 2–4 YEARS

Piaget characterized the 2- to 6-year-old stage as preoperational. This stage begins when language has facilitated the creation of mental images in the symbolic sense. The child begins to manipulate the symbolic world; sorts out reality from fantasy imperfectly; and may be terrified of dreams, wishes, and foolish threats. Most of the child’s perception of the world is egocentric or interpreted in reference to his or her needs or influence. Cause-effect relationships are confused with temporal ones or interpreted egocentrically. For example, children may focus their understanding of divorce on themselves (“My father left because I was bad” or “My mother left because she didn’t love me”). Illness and the need for medical care are also commonly misinterpreted at this age. The child may make a mental connection between a sibling’s illness and a recent argument, a negative comment, or a wish for the sibling to be ill. The child may experience significant guilt unless the parents are aware of these misperceptions and take time to deal with them.

At this age, children also endow inanimate objects with human feelings. They also assume that humans cause or create all natural events. For instance, when asked why the sun sets, they may say, “The sun goes to his house” or “It is pushed down by someone else.” Magical thinking blossoms between ages 3 and 5 years as symbolic thinking incorporates more elaborate fantasy. Fantasy facilitates development of role playing, sexual identity, and emotional growth. Children test new experiences in fantasy, both in their imagination and in play. In their play, children often create magical stories and novel situations that reflect issues with which they are dealing, such as aggression, relationships, fears, and control. Children often invent imaginary friends at this time, and nightmares or fears of monsters are common. At this stage, other children become important in facilitating play, such as in a preschool group. Play gradually becomes more cooperative; shared fantasy leads to game playing. Freud described the oedipal phase between ages 3 and 6 years, when there is strong attachment to the parent of the opposite sex. The child’s fantasies may focus on play-acting the adult role with that parent, although by age 6 years oedipal issues are usually resolved and attachment is redirected to the parent of the same sex.

EARLY SCHOOL YEARS: AGES 5–7 YEARS

Attendance at kindergarten at age 5 years marks an acceleration in the separation-individuation theme initiated in the preschool years. The child is ready to relate to peers in a more interactive manner. The brain has reached 90% of its adult weight. Sensorimotor coordination abilities are maturing and facilitating pencil-and-paper tasks and sports, both part of the school experience. Cognitive abilities are still at the preoperational stage, and children focus on one variable in a problem at a time. However, most children have mastered conservation of length by age 5½ years, conservation of mass and weight by 6½ years, and conservation of volume by 8 years.

By first grade, there is more pressure on the child to master academic tasks—recognizing numbers, letters, and words and learning to write. Piaget described the stage of concrete operations beginning after age 6 years, when the child is able to perform mental operations concerning concrete objects that involve manipulation of more than one variable. The child is able to order, number, and classify because these activities are related to concrete objects in the environment and because these activities are stressed in early schooling. Magical thinking diminishes greatly at this time, and the reality of cause-effect relationships is better understood. Fantasy and imagination are still strong and are reflected in themes of play.

MIDDLE CHILDHOOD: AGES 7–11 YEARS

Freud characterized ages 7–11 years as the latency years, during which children are not bothered by significant aggressive or sexual drives but instead devote most of their energies to school and peer group interactions. In reality, throughout this period there is a gradual increase in sex drive, manifested by increasingly aggressive play and interactions with the opposite sex. Fantasy still has an active role in dealing with sexuality before adolescence, and fantasies often focus on movie and music stars. Organized sports, clubs, and other activities are other modalities that permit preadolescent children to display socially acceptable forms of aggression and sexual interest.

For the 7-year-old child, the major developmental tasks are achievement in school and acceptance by peers. Academic expectations intensify and require the child to concentrate on, attend to, and process increasingly complex auditory and visual information. Children with significant learning disabilities or problems with attention, organization, and impulsivity may have difficulty with academic tasks and subsequently may receive negative reinforcement from teachers, peers, and even parents. Such children may develop a poor self-image manifested as behavioral difficulties. The pediatrician must evaluate potential learning disabilities in any child who is not developing adequately at this stage or who presents with emotional or behavioral problems. The developmental status of school-aged children is not documented as easily as that of younger children because of the complexity of the milestones. In the school-aged child, the quality of the response, the attentional abilities, and the child’s emotional approach to the task can make a dramatic difference in success at school. The clinician must consider all of these aspects in the differential diagnosis of learning disabilities and behavioral disorders.

Bjorklund FP: Children’s Thinking. Cenage Learning, Independence, KY; 1995.

Dixon SD, Stein MT: Encounters With Children: Pediatric Behavior and Development, 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby-Year Book; 2006.

Feldman HM: Evaluation and management of language and speech disorders in preschool children. Pediatr Rev 2005;26:131 [PMID: 15805236].

Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM: Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children and Adolescents, 3rd ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008.

Squires J, Bricker D: Ages and Stages Questionnaires, 3rd ed. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing; 2009.

BEHAVIORAL & DEVELOPMENTAL VARIATIONS

Behavioral and developmental variations and disorders encompass a wide range of issues of importance to pediatricians. Practitioners will be familiar with most of the problems discussed in this chapter; however, with increasing knowledge of the factors controlling normal neurologic and behavioral development in childhood, new perspectives on these disorders and novel approaches to their diagnosis and management are emerging.

Variations in children’s behavior reflect a blend of intrinsic biologic characteristics and the environments with which the children interact. The next section focuses on some of the more common complaints about behavior encountered by those who care for children. These behavioral complaints are by and large normal variations in behavior, a reflection of each child’s individual biologic and temperament traits and the parents’ responses. There are no cures for these behaviors, but management strategies are available that can enhance the parents’ understanding of the child and the child’s relationship to the environment. These strategies also facilitate the parents’ care of the growing infant and child.

The last section of this chapter discusses developmental disorders of cognitive and social competence. Diagnosis and management of these conditions requires a comprehensive and often multidisciplinary approach. The healthcare provider can play a major role in diagnosis, in coordinating the child’s evaluation, in interpreting the results to the family, and in providing reassurance and support.

Capute AJ, Accardo PJ (eds): Developmental Disabilities in Infancy and Childhood, 2nd ed. Vol. 1, Neurodevelopmental Diagnosis and Treatment. Vol. 2, The Spectrum of Developmental Disabilities. Brookes/Cole; 1996.

Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee, American Academy of Pediatrics: The medical home. Pediatrics 2002;110:184 [PMID: 12093969].

Wolraich ML et al (eds): Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics: Evidence and Practice. Mosby/Elsevier; 2008.

Wolraich ML et al: The Classification of Child and Adolescent Mental Diagnoses in Primary Care: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Primary Care (DSM-PC) Child and Adolescent Version. American Academy of Pediatrics; 1996.

NORMALITY & TEMPERAMENT

The physician confronted by a disturbance in physiologic function rarely has doubts about what is atypical. Variations in temperament and behavior are not as straightforward. Labeling such variations as disorders implies that a disease entity exists.

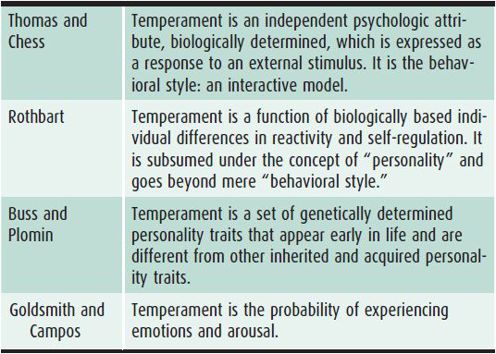

The behaviors described in this section are viewed as part of a continuum of responses by the child to a variety of internal and external experiences. Variations in temperament have been of interest to philosophers and writers since ancient times. The Greeks believed there were four temperament types: choleric, sanguine, melancholic, and phlegmatic. In more recent times, folk wisdom has defined temperament as a genetically influenced behavioral disposition that is stable over time. Although a number of models of temperament have been proposed, the one usually used by pediatricians in clinical practice is that of Thomas and Chess, who describe temperament as being the “how” of behavior as distinguished from the “why” (motivation) and the “what” (ability). Temperament is an independent psychological attribute that is expressed as a response to an external stimulus. The influence of temperament is bidirectional: The effect of a particular experience will be influenced by the child’s temperament, and the child’s temperament will influence the responses of others in the child’s environment. Temperament is the style with which the child interacts with the environment.

The perceptions and expectations of parents must be considered when a child’s behavior is evaluated. A child that one parent might describe as hyperactive might not be characterized as such by the other parent. This truism can be expanded to include all the dimensions of temperament. Thus, the concept of “goodness of fit” comes into play. For example, if the parents want and expect their child to be predictable but that is not the child’s behavioral style, the parents may perceive the child as being bad or having a behavioral disorder rather than as having a developmental variation. An appreciation of this phenomenon is important because the physician may be able to enhance the parents’ understanding of the child and influence their responses to the child’s behavior. When there is goodness of fit, there will be more harmony and a greater potential for healthy development not only of the child but also of the family. When goodness of fit is not present, tension and stress can result in parental anger, disappointment, frustration, and conflict with the child.

Other models of temperament include those of Rothbart, Buss and Plomin, and Goldsmith and Campos (Table 3–4). All models seek to identify intrinsic behavioral characteristics that lead the child to respond to the world in particular ways. One child may be highly emotional and another less so (ie, calmer) in response to a variety of experiences, stressful or pleasant. The clinician must recognize that each child brings some intrinsic, biologically based traits to its environment and that such characteristics are neither good nor bad, right nor wrong, normal nor abnormal; they are simply part of the child. Thus, as one looks at variations in development, one should abandon the illness model and consider this construct as an aid to understanding the nature of the child’s behavior and its influence on the parent–child relationship.

Table 3–4. Theories of temperament.

Barr RG: Normality: a clinically useless concept: the case of infant crying and colic. J Dev Behav Pediatr 1993;14:264 [PMID: 8408670].

Goldsmith HH et al: Roundtable: what is temperament? Four approaches. Child Dev 1987;58:505 [PMID: 3829791].

Nigg JT: Temperament and developmental psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2006;47:395–422 [PMID: 16492265].

Prior M: Childhood temperament. J Child Psychol Psychiatr 1992; 33:249 [PMID: 1737829].

Thomas A, Chess S: Temperament and Development. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel; 1977.

ENURESIS & ENCOPRESIS

Enuresis and encopresis are common childhood problems encountered in the pediatric and family practitioner’s office. Bedwetting is particularly common with about 20% of children in the first grade occasionally wetting the bed and 4% wetting the bed two or more times a week. Enuresis is more common in boys than in girls. In a recent large US study, the prevalence of enuresis among boys 7 and 9 years was 9% and 7%, respectively, and among girls at those ages, 6% and 3%, respectively. The data on constipation and encopresis seem less clear with about 1%–3% of children experiencing this problem, but with anywhere from 0.3% to 29% of children worldwide experiencing constipation. Overall, encopresis/constipation accounts for 3% of referrals to pediatricians’ offices. What is very striking, however, is that constipation and enuresis often co-occur; in such a case the constipation needs to be dealt with before the enuresis can be addressed.

ENURESIS

Enuresis is defined as repeated urination into the clothing during the day and into the bed at night by a child who is chronologically and developmentally older than 5 years; this pattern of urination must occur at least twice a week for 3 months. Enuresis has been categorized by the International Children’s Continence Society as monosymptomatic or nonmonosymptomatic. Monosymptomatic enuresis is uncomplicated nocturnal enuresis (NE; must never have been dry at night for over 6 months with no daytime accidents); it is a reflection of a maturational disorder and there is no underlying organic problem. Complicated or nonmonosymptomatic enuresis often involves NE and daytime incontinence and often reflects an underlying disorder. The evaluation of both forms needs to take into consideration both the medical and psychological implications of these conditions.

Monosymptomatic enuresis reflects a delay in achieving nighttime continence and reflects a delay in the maturation of the urological and neurological systems. Both micturition and anorectal evacuation are dependent on neural connections and communications between the frontal lobes, locus ceruleus, mid pons, sacral voiding center, and the bladder and rectum. With respect to enuresis, most children are continent at night within 2 years of achieving daytime control. However, 15.5% of 7.5-year-old children wet the bed but only about 2.5% meet the criteria for enuresis. With each year of age the frequency of bedwetting decreases: by 15 years only about 1%–2% of children continue to wet. This occurs more commonly among boys than girls.

The causes for NE are varied and probably interact with one another. Genetic factors are strongly implicated, as enuresis tends to run in families. Many children with NE have a higher threshold for arousal and do not awake to the sensation of a full bladder. NE also can be a result of overproduction of urine from decreased production of desmopressin or a resistance to antidiuretic hormone. In such cases, the bladder has decreased functional capacity and empties before it is filled.

The evaluation of a child with NE involves a complete history and physical examination to rule out any anatomical abnormalities, underlying pathology, or the presence of constipation. In addition, every child with NE should undergo a urinalysis including a specific gravity. A urine culture should be obtained, especially in girls.

Treatment involves education and the avoidance of being judgmental and shaming the child. Most children feel ashamed and the goal of treatment is to help the child establish continence and maintain his or her self-esteem. A variety of behavioral strategies have been employed such as limiting liquids before sleep and awakening the child at night so that he/she can go to the toilet. Central to this simple strategy is consistency on the parents’ part and the need for the child to be completely awake. If this simple approach is unsuccessful, the use of bedwetting alarms is suggested. Every time the alarm goes off, the child should go to the toilet and void. Therapy needs to be continued for at least 3 months and used every night. Critical to the success of therapy is that parents need to be active participants and get up with the child, as many children will just turn off the alarm and go back to sleep. The alarm system, which is a form of cognitive behavioral therapy, has been found to cure two-thirds of affected children and should be highly recommended to affected children and their parents as a safe, effective treatment for NE. The most common cause of failure of this intervention is that the child doesn’t awaken or the parents do not wake the child.

While behavioral strategies should be the first line of treatment, when these fail one may need to turn to medications. Desmopressin acetate (DDAVP), an antidiuretic hormone analogue, has been used successfully. DDAVP decreases urine production. Imipramine, a tricyclic antidepressant, also has been used successfully to control NE, although the mechanism of action is not understood. However, potential adverse side effects, including the risk of death with an overdose, suggest that imipramine should be used only as a last resort. Unfortunately, when such medications are stopped, there is a very high relapse rate.

Daytime incontinence or nonmonosymptomatic enuresis is more complicated than NE. Daytime continence is achieved by 70% of children by 3 years of age and by 90% of children by 6 years. When this is not the case, one needs to consider underlying pathology, including cystitis, diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, seizure disorders, neurogenic bladder, anatomical abnormalities of the urinary tract system such as urethral obstruction, constipation, and psychological stress and child maltreatment. A complete history and physical examination must be obtained, along with a diary that includes daily records of voiding and fecal elimination. Treatment must be directed at the underlying pathology and often requires the input of pediatric subspecialists. Following diagnosis, family support and education are essential.

ENCOPRESIS

Constipation (see Chapter 21) is defined by two or more of the following events for 2 months: (1) fewer than three bowel movements per week; (2) more than one episode of encopresis per week; (3) impaction of the rectum with stool; (4) passage of stool so large that it obstructs the toilet; (5) retentive posturing and fecal withholding; and (6) pain with defecation.

Encopresis is defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) as the repeated passage of stool into inappropriate places (such as in the underpants) by child who is chronologically or developmentally older than 4 years. Behavioral scientists often divide encopresis into (1) retentive encopresis, (2) continuous encopresis, and (3) discontinuous encopresis. In rare instances children have severe toilet phobia and so do not defecate into the toilet. It is critical to note that more than 90% of the cases of encopresis result from constipation. Thus, in the evaluation of a child with encopresis, one must rule out underlying pathology associated with constipation (see Chapter 21) while at the same time addressing functional and behavioral issues. Conditions associated with constipation include metabolic disorders such as hypothyroidism, neurologic disorders such as cerebral palsy or tethered cord, and anatomical abnormalities of the anus. In addition, children who have been continent can also develop encopresis as a response to stress or child maltreatment.

The prevalence of encopresis is somewhat difficult to precisely ascertain as it is a subject often kept secret by the family and the child. However, some authors report that 1%–3% of children ages 4–11 years of age suffer from encopresis. The highest prevalence is between 5 and 6 years of age.

A complete history and meticulous physical examination must be performed, including a rectal examination, particularly looking for abnormalities around the anus and spine. An abdominal radiograph can be helpful in determining the degree of constipation, the appearance of the bowel, and whether there is obstruction. Assuming no gastrointestinal abnormalities, initial intervention starts with treatment of constipation. Subsequently education, support, and guidance around evacuation are essential, including behavioral strategies such as having the child sit on the toilet after meals to stimulate the gastrocolic reflex. It is most important to avoid punishing the child and making him or her feel guilty and ashamed. Helping the child to clean himself and his clothing in a nonjudgmental, nonpunitive manner is far more productive approach than criticism and reproach. At the same time, if there is an underlying psychiatric disorder such as depression, the child should be treated for the mental health problem along with the treatment of the constipation.

When medical management of constipation is indicated, oral medication or an enema for “bowel cleanout” followed by oral medications should be used. Such treatment can be monitored by abdominal radiographs to be sure that the colon is clean. A bowel regimen needs to be established with the goal of the child achieving continence and defecating in the toilet bowl on a regular basis. The child should be encouraged to have a daily bowel movement, and the use of fiber, some laxatives, and even mineral oil can be helpful. Consultation with a gastroenterologist should be considered in more refractory cases.

Culbert TP, Banez GA: Integrative approaches to childhood constipation and encopresis. Pediatr Clin North Am 2007;54(6): 927–947 [PMID: 18061784].

Nijman, RJM: Diagnosis and management of urinary incontinence and functional fetal incontinence (encopresis) in children. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2008;37(3):731–748 [PMID: 18794006].

Reiner W: Pharmacotherapy in the management of voiding and storage disorders, including enuresis and encopresis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2008;47:491–498 [PMID: 18438186].

Robson WLM: Clinical practice. Evaluation and management of enuresis. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1429–1436 [PMID: 19339722].

Schonwald A, Rappaport LA: Elimination conditions. In: Wolraich ML et al (eds): Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics: Evidence and Practice. Mosby Elsevier; 2008:791–804.

COMMON DEVELOPMENTAL CONCERNS

COLIC

Infant colic is characterized by severe and paroxysmal crying that occurs mainly in the late afternoon. The infant’s knees are drawn up and its fists are clenched, flatus is expelled, the facies has a pained appearance, and there is minimal response to attempts at soothing. Studies in the United States have shown that among middle-class infants, crying occupies about 2 hours per day at 2 weeks of age, about 3 hours per day by 6 weeks, and gradually decreases to about 1 hour per day by 3 months. The word “colic” is derived from Greek kolikos (“pertaining to the colon”). Although colic has traditionally been attributed to gastrointestinal disturbances, this has never been proved. Others have suggested that colic reflects a disturbance in the infant’s sleep-wake cycling or an infant state regulation disorder. In any case, colic is a behavioral sign or symptom that begins in the first few weeks of life and peaks at age 2–3 months. In about 30%–40% of cases, colic continues into the fourth and fifth months.

A colicky infant, as defined by Wessel, is one who is healthy and well fed but cries for more than 3 hours a day, for more than 3 days a week, and for more than 3 weeks—commonly referred to as the “rule of threes.” The important word in this definition is “healthy.” Thus, before the diagnosis of colic can be made, the pediatrician must rule out diseases that might cause crying. With the exception of the few infants who respond to elimination of cow’s milk from its own or the mother’s diet, there has been little firm evidence of an association of colic with allergic disorders. Gastroesophageal reflux is often suspected as a cause of colicky crying in young infants. Undetected corneal abrasion, urinary tract infection, and unrecognized traumatic injuries, including child abuse, must be among the physical causes of crying considered in evaluating these infants. Some attempts have been made to eliminate gas with simethicone and to slow gut motility with dicyclomine. Simethicone has not been shown to ameliorate colic. Dicyclomine has been associated with apnea in infants and is contraindicated.

This then leaves characteristics intrinsic to the child (ie, temperament) and parental caretaking patterns as contributing to colic. Behavioral states have three features: (1) They are self-organizing—that is, they are maintained until it is necessary to shift to another one; (2) they are stable over several minutes; and (3) the same stimulus elicits a state-specific response that is different from other states. The behavioral states are (among others) a crying state, a quiet alert state, an active alert state, a transitional state, and a state of deep sleep. The states of importance with respect to colic are the crying state and the transitional state. During transition from one state to another, infant behavior may be more easily influenced. Once an infant is in a stable state (eg, crying), it becomes more difficult to bring about a change (eg, to soothe). How these transitions are accomplished is probably influenced by the infant’s temperament and neurologic maturity. Some infants move from one state to another easily and can be diverted easily; other infants sustain a particular state and are resistant to change.

The other factor to be considered in evaluating the colicky infant is the feeding and handling behavior of the caregiver. Colic is a behavioral phenomenon that involves interaction between the infant and the caregiver. Different caregivers perceive and respond to crying behavior differently. If the caregiver perceives the crying infant as being spoiled and demanding and is not sensitive to or knowledgeable about the infant’s cues and rhythms—or is hurried and “rough” with the infant—the infant’s ability to organize and soothe him- or herself or respond to the caregiver’s attempts at soothing may be compromised. Alternatively, if the temperament of an infant with colic is understood and the rhythms and cues deciphered, crying can be anticipated and the caregiver can intervene before the behavior becomes “organized” in the crying state and more difficult to extinguish.

Management

Management

Several approaches can be taken to the management of colic.

1. Parents may need to be educated about the developmental characteristics of crying behavior and made aware that crying increases normally into the second month and abates by the third to fourth month.

2. Parents may need reassurance, based on a complete history and physical examination, that the infant is not sick. Although these behaviors are stressful, they are normal variants and are usually self-limited. This discussion can be facilitated by having the parent keep a diary of crying and weight gain. If there is a diurnal pattern and adequate weight gain, an underlying disease process is less likely to be present. Parental anxiety must be relieved, because it may be contributing to the problem.

3. For parents to effectively soothe and comfort the infant, they need to understand the infant’s cues. The pediatrician (or nurse) can help by observing the infant’s behavior and devising interventions aimed at calming both the infant and the parents. One should encourage a quiet environment without excessive handling. Rhythmic stimulation such as gentle swinging or rocking, soft music, drives in the car, or walks in the stroller may be helpful, especially if the parents are able to anticipate the onset of crying. Another approach is to change the feeding habits so that the infant is not rushed, has ample opportunity to burp, and, if necessary, can be fed more frequently so as to decrease gastric distention if that seems to be contributing to the problem.

4. Medications such as phenobarbital elixir and dicyclomine have been found to be somewhat helpful, but their use is to be discouraged because of the risk of adverse reactions and overdosage. A trial of ranitidine hydrochloride or other proton pump inhibitor might be of help if gastroesophageal reflux is contributing to the child’s discomfort.

5. For colic that is refractory to behavioral management, a trial of changing the feedings, and eliminating cow’s milk from the formula or from the mother’s diet if she is nursing, may be indicated. The use of whey hydrolysate formulas for formula-fed infants has been suggested.

Barr RG: Colic and crying syndromes in infants. Pediatrics 1998;102:1282 [PMID: 9794970].

Barr RG et al (eds): Crying as a Sign, a Symptom, and a Signal: Clinical, Emotional, and Developmental Aspects of Infant and Toddler Crying. London, UK: MacKeith Press; 2000.

Cohen-Silver J, Ratnapalan S: Management of infantile colic: a review. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2009;48:14–17 [PMID: 18832537].

Garrison MM, Christakis DA. A systematic review of treatments for infant colic. Pediatrics 2000;106:1563–1569 [PMID: 10888690].

Herman M, Le A: The crying infant. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2007, Nov;25(4):1137–1159 [PMID: 17950139].

Turner JL, Palamountain S: Clinical features and etiology of colic. In: Rose BD (ed): UpToDate. UpToDate; 2005.

Turner JL, Palamountain S: Evaluation and management of colic. In: Rose BD (ed): UpToDate. UpToDate; 2005.

Zero to Three. http://www.zerotothree.org/childdevelopment/challenging-behavior/colic-behaviors.html.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree