The main risk factors for cervical cancer include exposure to HPV, smoking, parity, and immunosuppression; other factors that have been linked with cervical cancer are race/socioeconomic status and sexually transmitted infections.

HPV infection is present in 99.7% of all cervical cancers. HPV is a nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA virus. The DNA is enclosed in a capsid shell with

major L1 and minor L2 structural proteins. The virus is spread through sexual contact. Thus, traditional risk factors for cervical cancer include early age at first coitus, multiple sexual partners, multiparity, lack of barrier contraception, and history of sexually transmitted infections.

High-risk HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 45, 52, and 58 are associated with 95% of squamous cell carcinomas of the cervix. HPV 16 is most commonly linked with squamous cell cervical cancer. HPV 18 is most commonly present in adenocarcinoma.

Most HPV infections are transient, resulting in either no change in the cervical epithelium or low-grade intraepithelial lesions that are often spontaneously cleared. The progression from high-grade lesion to invasive cancer takes approximately 8 to 12 years, yielding a long preinvasive state with multiple opportunities for detection through screening.

Cigarette smoking is an independent risk factor in the development of cervical disease. Smokers have a 4.5-fold increased risk of carcinoma in situ (CIS) compared with matched controls. Additionally, an increased risk of cervical cancer has been noted in women exposed passively to tobacco smoke. The potential effect of smoking appears to be limited to squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix.

Immunosuppression may increase the risk of developing cervical cancer, with more rapid progression from preinvasive to invasive lesions. Patients with HIV infection present earlier and with more advanced disease than noninfected patients. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has described cervical cancer as an AIDS-defining illness.

Race and socioeconomic status

The incidence per 100,000 women per year of cervical cancer in the United States varies by ethnicity/race.

African Americans, 11; Caucasians, 8; Native Americans, 12; Hispanics, 6; and Asians, 7

These differences are partially accounted for by the increased risk of cervical cancer among women of low socioeconomic status. When access to care is made equal, the excessive risk of cervical cancer precursor lesions among African American women decreases.

Racial differences are also apparent in survival; 58% of all African Americans with cervical cancer survive 5 years, compared with 72% of all whites.

Early symptoms:

Abnormal vaginal bleeding may take the form of postcoital, intermenstrual, or postmenopausal bleeding.

Serosanguineous or yellowish vaginal discharge, at times foul-smelling

Dyspareunia

Late symptoms:

Hematometra due to occlusion of the endocervical canal

Symptomatic anemia

Pelvic pain

Sciatic and back pain can be related to sidewall extension, hydronephrosis, or metastasis.

Bladder or rectal invasion by advanced-stage disease may produce urinary or rectal symptoms (e.g., vaginal passage of stool or urine, hematuria, urinary frequency, hematochezia).

Lower extremity swelling from occlusion of pelvic lymphatics or thrombosis of the external iliac vein.

Most women with cervical cancer have a visible cervical lesion.

On speculum examination, cervical cancer may appear as an exophytic cervical mass (Fig. 46-1) that characteristically bleeds on contact. Endophytic tumors develop entirely within the endocervical canal, and the external cervix may appear normal. In these cases, bimanual examination may reveal a firm, indurated, and often barrel-shaped cervix. The vagina should be inspected for extension of disease. Rectal exam provides information regarding the nodularity of the uterosacral ligaments and helps determine extension of disease into the parametrium.

On general physical examination, advanced cervical cancer may present with pleural effusions, ascites, and/or lower extremity edema. Unilateral lower extremity edema may indicate involvement of the pelvic sidewall. Groin and supraclavicular lymph nodes may be indurated or enlarged, indicating spread of disease.

With obvious exophytic lesions, cervical biopsy is usually all that is needed for histologic confirmation.

In patients with a grossly normal cervix and abnormal cytology on Pap smear, colposcopic examination with directed biopsies and endocervical curettage (ECC) is necessary. See Chapter 45.

If a definite diagnosis of cervical cancer cannot be made on the basis of office biopsies, diagnostic cervical conization may be necessary.

Cervical cancer usually spreads by direct extension.

Parametrial extension: The lateral spread of cervical cancer occurs through the cardinal ligament lymphatics and vessels, and significant involvement of the medial portion of this ligament may result in ureteral obstruction.

Vaginal extension: The upper vagina is frequently involved (50% of cases) when the primary tumor has extended beyond the confines of the cervix.

Bladder and rectal involvement: Anterior and posterior spread of cervical cancer to the bladder and rectum is uncommon in the absence of lateral parametrial disease.

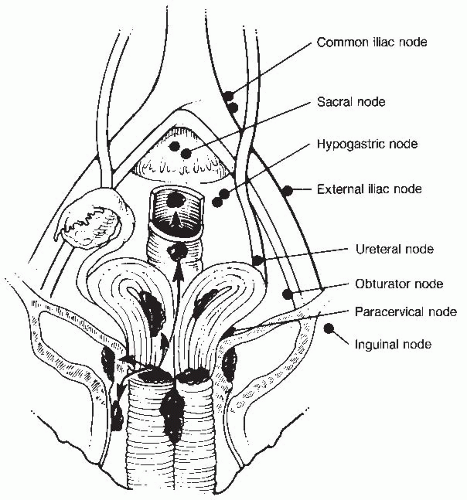

Cervical cancer may also progress via lymphatic spread (Fig. 46-2). The cervix is drained by preureteral, postureteral, and uterosacral lymphatic channels.

The following are considered first station nodes: obturator, external iliac, hypogastric, parametrial, presacral, and common iliac.

Para-aortic nodes are second station, are rarely involved in the absence of primary nodal disease, and are considered metastases.

The percentage of involved lymph nodes increases directly with primary tumor volume and stage of disease.

Hematologic spread metastases from cervical carcinomas occur but are less frequent and are usually seen late in the course of the disease.

Staging of cervical cancer is based on clinical rather than surgical evaluation (Tables 46-1 and 46-2).

Routine laboratory studies should include a complete blood count, complete metabolic profile, and urinalysis. No tumor marker has achieved widespread acceptance.

Inspection and palpation should begin with the cervix, vagina, and pelvis and continue with examination of extrapelvic areas, including the abdomen and supraclavicular lymph nodes.

Lymphangiograms, arteriograms, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography, laparoscopy, or laparotomy findings are not used for clinical staging, but their results may be valuable for planning treatment. Imaging studies beyond chest x-ray should be obtained only when the findings will have an impact on treatment.

Cervical cancer is staged according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) system (see Table 46-1; Fig. 46-3). Lymph—vascular involvement does not alter the classification.

When doubt exists concerning the stage to which a tumor should be assigned, the earlier stage is chosen. Once a clinical stage has been determined and treatment

has begun, subsequent findings do not alter the assigned stage. Overstaging and understaging of the parametria are problematic and may affect therapeutic decisions. FIGO stage correlates with prognosis, and strict adherence to the rules of clinical staging is necessary for comparison of results between institutions.

The distribution of patients by clinical stage is as follows: 38% stage I, 32% stage II, 25% stage III, 4% stage IV. Clinical stage of disease at the time of presentation is the most important determinant of survival regardless of treatment modality.

Five-year survival declines as FIGO stage at diagnosis increases from stage IA (95%) to stage IV (14%).

Only the subclassifications of stage I (IA1, IA2) require pathologic assessment.

Vast discrepancies can exist between clinical staging and surgicopathologic findings, such that clinical staging fails to identify extension of disease to the para-aortic

nodes in 7% of patients with stage IB disease, 18% with stage IIB, and 28% with stage III. Thus, some clinicians emphasize surgical staging in women with locally advanced cervical carcinoma to identify occult tumor spread and allow treatment of metastatic disease beyond the traditional pelvic radiation field.

TABLE 46-1 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Staging System for Carcinoma of the Cervix (2009) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 46-2 Staging Procedures for Cervical Cancer

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

|---|