FIGURE 5-1 Photograph of father with untreated central synpolydactyly.

CLINICAL QUESTIONS

- Under which category is central polydactyly classified?

- What are the genetics of this malformation?

- Are there associated syndromes or conditions?

- What is the spectrum of presentation?

- When should surgery be performed?

- What are the surgical techniques?

- What are the expected results?

- What are the complications of surgical intervention?

- What is the natural history if untreated?

THE FUNDAMENTALS

Six aligned, mobile digits, whether independent or syndactylized, do not negatively impair function. However, digital crossover during flexion for grasp and/or failure to clear a digit from the palm during release will limit hand use. Central polydactyly is a rare condition, much less common than preaxial (thumb) or postaxial (small finger) polydactyly which can impair grasp and release function. Central polydactyly or synpolydactyly can have psychosocial implications, including simple but potentially isolating issues such as learning to count on your fingers in preschool with peers.

Etiology and Epidemiology

Central polydactyly has been classified by the International Federation of Societies for Surgery of the Hand1 as a type III polydactyly The Japanese Society for Surgery of the Hand has proposed this malformation be classified with cleft hands and osseous syndactyly under a new category of failure of ray induction.2 This is based on experimental work with embryonic rats treated with a chemotherapeutic agent (busulfan) in which the tetrogenic effects resulting in cleft hands, central polydactylies, and osseous syndactylies were all from defects in the central hand plate due to failure of induction.3 The experimental data indicate there is diffuse cell death in the central ectoderm and mesoderm with decreased expression of fibroblast growth factor in the apical ectodermal ridge as well as bone morphogenetic protein-4 and sonic hedgehog in the mesoderm. A similar pattern of interdigital apoptosis and cartilage condensation leads to abnormal induction of digital rays in cleft hands, central polydactylies, and osseous syndactylies.4,5

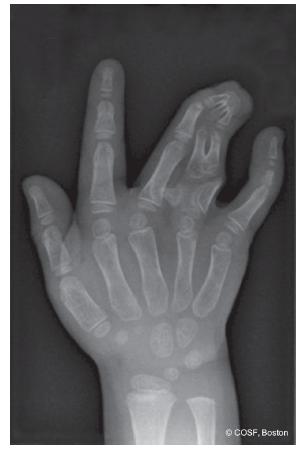

Central synpolydactyly was one of the first two limb malformations identified as being caused by a genetic mutation in a homeobox (HOX) gene.6 Specifically, it is deletions in HOXD13 on chromosome 2 (2q31) that result in this malformation. It is an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern.7 There is a spectrum of presentation in each family but generally with marked osseous deformity (Figure 5-2).8

FIGURE 5-2 Anteroposterior radiograph of complex central synpolydactyly with osseous synostoses distal phalanges, bifid middle phalanges ring finger polydactyly, bracket epiphysis proximal phalanx, and cross bone between the ring polydactyly and the middle finger.

Clinical Evaluation

Central polydactyly by definition involves the ring, long, and/or index fingers. It is much less common than postaxial polydactyly or preaxial polydactyly. It occurs most often in the ring > long > index fingers. Bilateral involvement is typical, and associated foot anomalies are frequent. Partial duplications can occur and appear similar to those partial polydactylies of the thumb and small finger by both clinical exam and radiographs. Independent, mobile complete polydactylies also occur. At times, it is unclear which central digit is duplicated. In the presence of syndactyly, the numbers of bones and their alignment can be hard to assess by clinical exam. Radiographs are necessary to determine the presence of bracketed epiphyses, crossed bones, bifid bones, synostoses, joint malalignment, and physeal growth potential. The osseous abnormalities may extend into the palm. Radiographs are mandatory to decide on surgical intervention and planning.

Central polydactyly is associated with Grebe chondrodysplasia and syndrome C (trigonocephaly). Central synpolydactyly is an autosomal dominant inherited mutation of the HOXD13 gene on chromosome 2. Children of consanguineous pregnancies have a more severe form of the osseous disorder that extends into the metacarpals and carpus, metatarsals and tarsal bones.7

Surgical Indications

It is what you learn after you know it all that counts.

—Earl Weaver

The hardest decision in central synpolydactyly is to know when natural history will be better than the outcomes of surgical intervention. The biggest risk to surgical seindenttion is transforming a highly functional block of syndactylized digits into a five-digit hand with less functional ability. Unfortunately there is a risk that surgery can result in stiffness, malangulation, and malrotation that negatively impacts hand function. The parents can be on opposite sides of the fence on this decision. The affected parent with the genetic condition often views the psychosocial and functional future of his or her child differently than the unaffected parent. The parents and grandparents often assume that current surgeons are smarter and more skilled than a generation ago. Why shouldn’t they? Hasn’t everything else from computers to televisions to cars improved in technical expertise? It is a hard negotiation, a difficult decision, and should not be taken lightly. You have to be the child’s advocate and realistic about your surgical capabilities. If in doubt, seek additional opinions.

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Life is not always a matter of holding good cards, but sometimes of playing a poor hand well.

—Robert Louis Stevenson

Ray Resection

Ray Resection

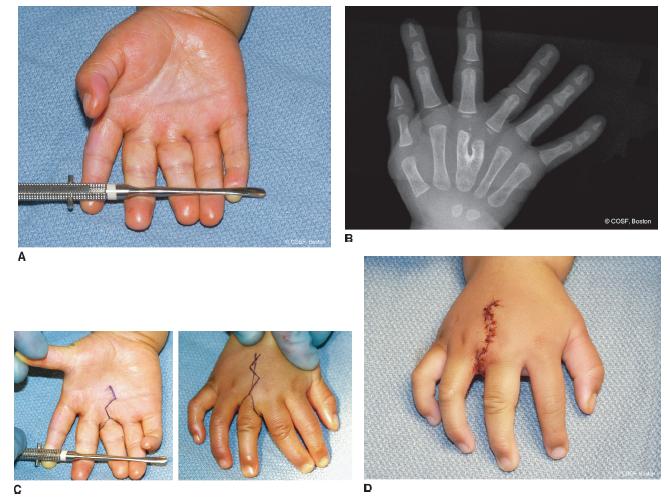

A central digit duplication with independent, aligned, adjacent fingers is the best indication for surgical reconstruction (Figure 5-3A). The absence of phalangeal bony synostosis or joint fusion and the presence of mobile metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints is ideal for reconstruction. Radiographs usually reveal a bifid (Figure 5-3B) or duplicated metacarpal. When there is no or limited major soft tissue (tendons, nerves) interconnections, a ray resection will yield excellent longterm results.

FIGURE 5-3 A: Palmar views of central polydactyly with mobile, independent digits. The middle finger here is the polydactylous digit. B: Radiograph of the same patient with duplicated phalanges and bifid metacarpal. C: Surgical incision markings for excision of ulnar middle finger and reconstruction of web between the radial middle finger and the ring finger. Note the nonlinear Z-plasty incision is preferred to a longitudinal incision. D: Intraoperative closure after ray resection and reconstruction of web.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree