Fig. 14.1

Germinoma resembles the primordial germ cell tumor of the gonads. Teratoma mimics the fetus itself, yolk sac tumor resembles the yolk sac, choriocarcinoma is similar to trophoblast or placenta, and embryonal carcinoma is composed of immature embryonic tissues (Reprinted from [69])

Gonadotropins are considered to have a potential role in the etiology due to the midline location of GCTs, the neighborhood to diencephalic centers that regulate gonadotropins, and the increased prevalence in children of peripubertal age and in boys affected by Klinefelter syndrome (47, XXY) [10, 11]. Several case reports describe GCTs affecting siblings or children with NF-1 or Down syndrome [12–19] hypothesizing potential genetic links. The occurrence of extracranial germ cell tumors in patients years after successful treatment for CNS GCT may as well be suggestive of a possible genetic disposition [20, 21].

Germinoma

Germinomas account for approximately 60–70 % of intracranial germ cell tumors [5]. Most germinomas develop in the midline structures, namely the suprasellar and pineal regions [22]. Occurrences outside the midline and in the basal ganglia are rare [23, 24]. Progression-free survival (PFS) in germinomas is excellent with 5-year overall survival (OS) exceeding 90 % in retrospective and prospective series [6, 25, 26].

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation is determined by the location of the germinoma. Long-lasting histories up to years are not uncommon. Diabetes insipidus, a symptom of the vast majority of patients with suprasellar and bifocal germinoma, can remain clinically balanced and undiagnosed for a prolonged time period. Hence diligent history taking and review of polyuria and polydipsia is important. Symptoms of increased fluid intake, weight loss, and personality changes in an academic high achieving, peripubertal girl may mislead to an inappropriate diagnosis of an eating behavior disorder. New onset of diabetes insipidus should prompt diagnostic workup including brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In case of documented pituitary stalk thickening, a careful clinical and imaging follow-up is recommended as about ~15–25 % of affected individuals may eventually develop germinoma [27, 28]. Other symptoms associated with suprasellar germinoma location are visual disturbances and endocrinopathies.

The most common symptoms of a pineal germinoma are symptoms of increased intracranial pressure due to obstruction of the aqueduct and Parinaud’s syndrome. This syndrome is named for Henri Parinaud, French ophthalmologist (1844–1905), and its component of upward gaze palsy is most apparent at clinical presentation.

Basal ganglia germinoma accounts for 4–10 % of germinoma and is often characterized by insidious onset of symptoms over a long period of time (1–4.5 years). The presentation is generally different from midline germinoma and can include hemiparesis or choreoathetotic movements, personality changes, and ocular and speech disturbances.

Radiology

Classical imaging characteristics of suprasellar and pineal (or bifocal) germinoma are homogenous iso- or hypointense lesions on T1 weighted MRI and iso- or hyperintense on T2 weighted MRI (iso- or hyperdense on computed tomography—CT) with avid enhancement after contrast administration. Ventricular dissemination is not exceptional and usually characterized by linear or nodular enhancement along the ependymal ventricular lining. Basal ganglia germinoma may lack this avid enhancement and sometimes show no or little mass effect especially in the early stages of the disease. Ipsilateral cerebral and/or brainstem atrophy (Wallerian degeneration) is present in one third of patients with basal ganglia germinoma [29].

Tumor Markers

Intracranial germ cell tumors can secrete tumor markers in the bloodstream and/or in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Most germinomas are marker negative and, in particular, they never secrete alpha-fetoprotein (AFP). However some germinomas may secrete human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG and hCGβ) either in serum or in the CSF due to the presence of syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells (STGCs). Retrospective and prospective analyses found elevated hCG levels in up to 40 % of germinoma patients [26, 30, 31]. The majority of cases have elevated hCG levels solely in CSF; however, the presence of both or elevated value in serum with normal value in CSF is described [31]. Sampling artifacts including the short half-life of hCG (1.5 days) may contribute to some variability in these findings.

There are conflicting data regarding the maximum level of hCG in germinoma and its prognostic significance. Moderate elevation of hCG in serum or CSF is considered diagnostic for germinoma, and a level below 50 IU/L is the threshold used in Europe and North America. The International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP-CNS-GCT) study defines tumors exceeding hCG > 50 IU/L as malignant secreting NGGCT. By contrast, in Japan, biopsy-proven germinomas are all classified as germinoma irrespective of their level of hCG secretion [32].

Some authors have suggested a different prognosis for germinoma with elevated level of hCG. One study reported a 10-year survival advantage for patients with nonsecreting germinomas (90 %) compared to those with elevated hCG serum levels (60 %) [33]. However, most other studies did not find such differences in outcome [22, 30, 34, 35]. The current ongoing Children’s Oncology Group germ cell tumor study increased the hCG threshold for eligibility into the germinoma treatment stratum, allowing patients to be enrolled as long as hCG level does not exceed 100 IU/L either in serum or CSF.

s-Kit in Germinoma

Immunohistochemical studies have shown that s-kit is highly expressed in germinoma cells. CSF studies have shown high levels of soluble-kit (s-kit) in patients with germinomas (with or without STGCs) compared to patients with NGGCTs [36]. s-Kit levels were also correlated with the clinical course of the disease, with higher s-kit concentration in samples obtained before treatment and in those collected at the time of tumor recurrence. These data suggest that CSF s-kit may represent a valuable tumor marker of germinomatous components.

Staging

As with malignant childhood brain tumors in general, MRI of the entire CNS (brain and spinal cord) at the time of initial diagnosis is essential for staging. If emergency surgery is deemed necessary for the patient (mostly for hydrocephalus management), then MRI of the spine—if not done prior to surgery—should be obtained within a 48–72 h window after the surgical intervention to avoid any artifact associated with the recent intervention. Tumor markers in serum and CSF are essential in midline lesions that are suspicious for GCT, and results will determine the need for biopsy, establish treatment strategy, and estimate prognosis. In addition, a lumbar CSF investigation for cytology prior to initiation of treatment is the gold standard; however, this may not always be feasible due to the presence of obstructive hydrocephalus and the associated life-threatening risk of brain herniation, particularly in the context of pineal germinomas. The CNS GCT SIOP trial allowed enrolment of patients if CSF cytology was undertaken either via ventricular route or lumbar puncture. Interestingly the Japanese working group dismisses CSF cytology because it is not taken into treatment considerations [37]. Data from prospective studies suggest [26, 38] that 15–20 % of germinoma patients have disseminated disease at diagnosis either on imaging (M+) or on CSF investigation (M1).

Treatment

Role of Radiation and Chemotherapy

Historically, craniospinal irradiation (CSI) has been the gold standard treatment for CNS germinoma [39–41]. Combined systemic chemotherapy with local irradiation has been introduced with the aim of reducing radiation doses and/or volume and herewith the incidence of late-onset sequelae while maintaining high cure rates [42, 43]. Focal radiation however resulted in increased number of ventricular relapses and subsequently whole-ventricular radiation (WVI) was utilized by the Japanese, French, and German working groups [26, 32, 38]. The relative contributions of chemotherapy and irradiation remain a topic of debate in the treatment of these highly curable CNS germinomas.

Radiation Therapy

The use of CSI dates from an era when staging was rarely performed and treatment was similar for non-metastatic and metastatic patients. Progressively, the relevance of CSI was questioned, particularly for patients with non-metastatic CNS germinoma. The low risk of isolated spinal relapse was initially suggested by Brada [44]. Rogers et al. conducted a meta-analysis of radiation therapy for germinoma patients and found a recurrence rate of 7.6 % after whole-brain or WVI and of 3.8 % after craniospinal radiation. No predilection for isolated spinal metastasis was found when CSI was omitted (2.9 % versus 1.2 %). The authors concluded that reduced-volume irradiation should replace CSI [25]. Ogawa’s retrospective review of the Japanese experience concurs with a low risk of spinal relapse with an incidence of 4 % (2/56) for patients treated with CSI versus 3 % (2/70) for patients treated without spinal radiation [22]. Excellent PFS for localized germinomas with the use of either whole-brain or whole-ventricular irradiation is reported by several institutions [6, 41, 45–47]. There are studies suggesting that radiation dose can be reduced to less than 36 Gy WVI without preirradiation chemotherapy [48, 49]. However the use of radiation therapy alone has been associated with a risk of extra CNS relapses [40]. In addition the late effects of radiation with respect to neurocognitive and endocrine function and quality of life are well recognized. A retrospective study evaluating quality of life in germinoma long-term survivors (n = 52) treated with radiation only identified significant issues: only 6 of 44 patients were married, 21 patients had no occupation, and 7 of 11 formerly employed patients had left their jobs [50]. In the hopes that reduced dose and volume of irradiation will diminish impact on neurocognitive function and quality of life in a meaningful way, neoadjuvant chemotherapy has been progressively introduced in the management of CNS germinoma.

Chemotherapy

Germinomas are highly sensitive to chemotherapy particularly to platinum compounds and cyclophosphamide [51, 52]. The largest chemotherapy-only experiences are reported in the First, Second, and Third International CNS Germ Cell Tumor Study. In the first study chemotherapy consisted of 4 cycles of carboplatin (500 mg/m2/day, day 1 and 2), etoposide (150 mg/m2/day, day 3), and bleomycin (15 mg/m2/day, day 3). Patients with complete radiological and tumor marker response proceeded to 2 more identical cycles, whereas cyclophosphamide (65 mg/kg) was added to the 3-drug regimen for those with incomplete response. Twenty-two of 45 CNS germinoma patients relapsed, and even though most relapsed patients were salvageable with radiation therapy, the 2-year OS in this study was only 84 % [53]. Nineteen germinoma patients were enrolled in the second study using an intensified cisplatin and cyclophosphamide-based chemotherapy induction. Despite proof of effectiveness with a high rate of complete remission, the 5-year event-free survival (EFS) and OS rates were unsatisfactory at 47 ± 2.3 % and 68 ± 2.2 %, respectively. Moreover chemotherapy was associated with unacceptable morbidity and mortality (four deaths), predominantly in patients with diabetes insipidus [54]. The third study included 25 patients and confirmed the inferior outcome of this strategy with a 6-year EFS of 45.6 % when avoiding radiation [55]. In conclusion current therapies cannot dismiss radiation without hampering the chances of EFS and OS.

Combined Chemo- and Radiation Therapy

Preirradiation chemotherapy with carboplatin, etoposide, and ifosfamide followed by focal irradiation (40 Gy) has been utilized in the SIOP-CNS-GCT-96 protocol for patients with non-metastatic germinomas. Physicians had the option to use this approach or alternatively CSI without chemotherapy. This prospective, multinational study included 190 patients with localized germinoma. The 5-year EFS and OS for patients treated with preirradiation chemotherapy (n = 65) were 88 ± 0.4 % and 96 ± 0.3 %, respectively, whereas the 5-year EFS and OS of patients treated with craniospinal radiation (n = 125) were 94 ± 0.2 % and 95 ± 0.2 %. While relapses (4/125) only occurred locally in the CSI group, 6 of 7 relapses occurred in the ventricular area in the chemotherapy/focal radiation treatment group [26]. As a consequence, the current open SIOP trial combines preirradiation chemotherapy with ventricular irradiation (24 Gy) with an additional boost of 16 Gy to the primary tumor bed in patients with localized disease. Metastatic germinoma patients will continue to be treated with CSI at doses outlined above as the 45 metastatic patients included in the aforementioned study showed an excellent 98 ± 0.2 % 5-year EFS and OS.

The risk of ventricular recurrence in patients treated with chemotherapy and focal radiation has also been well documented by the French and Japanese working groups. Alapetite et al. reported the SFOP (Societé Française d’Oncologie Pédiatrique) experience including 60 patients treated for CNS germinoma with a combination of carboplatin, etoposide, and ifosfamide followed by focal radiation (40 Gy). The 5-year EFS and OS were 84.2 % and 98.2 %, respectively. Ten of 60 patients relapsed at a median time of 32 (range: 10–121) months with the majority (n = 8) within the ventricular system [38]. The second trial of the Japanese GCT study group consisted of three cycles of carboplatin (450 mg/m2/day, day 1) and etoposide (150 mg/m2/day, day 1–3) chemotherapy followed by local irradiation (24 Gy). Five-year OS was 98 %. However 13 % of the patients (16/123) developed recurrence. In an interim analysis a high incidence of ventricular/locoregional relapses was reported [37]. As a consequence, current treatment in Japan, Europe, and North America combines chemotherapy with WVI. While the dose of WVI is 24 Gy in Europe and Japan, the current Children’s Oncology Trial evaluates the efficacy of a reduced dose of 18 Gy WVI (plus boost to tumor bed to a total of 30 Gy) in chemotherapy-responsive germinoma patients with localized disease.

Choices of Chemotherapeutic Agents

Among the variety of chemotherapy regimens, no protocol has suggested better activity or improved outcome. Therefore, the main issue in the management of germinoma patients relates to the short- and long-term safety of the chemotherapy used. While substitution of cisplatin with carboplatin has raised concerns because of inferior outcome in extracranial nonseminomatous germ cell tumors [56], carboplatin regimens have shown similar efficacy when compared with cisplatin regimens in CNS germinoma [51, 53].

The vast majority of patients with suprasellar germinoma suffer from diabetes insipidus. Cisplatin- or ifosfamide-based chemotherapy requires hyperhydration, which significantly increases the risk for electrolyte imbalances and consequent complications such as seizures [57]. A combination of carboplatin and etoposide chemotherapy is currently employed by the Japanese and North American working groups. This offers the advantage of easier outpatient administration and reduced risk of hyperhydration-associated metabolic complications.

Role of Surgery

The Need for Biopsy and Second-Look Surgery

As a matter of principle, a biopsy is required in case of marker-negative lesions. The choice of the technique (stereotactic, endoscopic, open craniotomy) and the goal of surgery (tissue diagnosis versus tumor resection) are complex and largely determined by the anatomy of the lesion (size, accessibility through the ventricle, etc.) as well as the presence and extent of ventriculomegaly. If the tumor is felt to be a germinoma, the general goal of surgical intervention (apart from hydrocephalus management) is tissue diagnosis and not tumor resection.

Symptomatic obstructive hydrocephalus may necessitate an emergent intervention such as placement of an external ventricular drain (EVD) or an endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV). At the time of ETV, many groups favor attempted tumor biopsy, to confirm the histology (keeping in mind the risk of sampling error in mixed pathology tumors).

The need for tissue biopsy in patients with a bifocal lesion, considered metasynchronous and not metastatic, is debated. In the current SIOP and North American protocols, a biopsy is not required if the clinical presentation, imaging characteristics, and tumor marker profile (AFP negative, no or mild elevation of hCG) are consistent with a bifocal germinoma. With very rare exceptions, bifocal lesions associated with negative tumor markers are almost always pure germinoma [26, 38, 58]. The current North American GCT trial does not mandate a biopsy for suprasellar, pineal, or unifocal ventricular lesions (radiologically consistent with germinoma) if AFP is negative and the hCG is elevated to ≤50 IU/L. However, in this protocol, a biopsy is required for patients with hCG values above 50 IU/L to a maximum of 100 IU/L. The Japanese approach has been surgical removal of lesions whenever feasible and subsequent treatment is based on the final pathology result.

Germinoma are highly chemosensitive and response to treatment is often obvious within days after the first cycle (Fig. 14.2). In our institutional experience an EVD can be removed within a week after the first chemotherapy cycle has been completed and before the patient becomes neutropenic. With this strategy VP shunts can most often be avoided. The presence of residual disease at the end of treatment is not predictive of worse outcome and patients with residual disease fare as well as those without [26]. Lack of chemotherapy responsiveness either in an hCG-positive or biopsy-proven germinoma raises concerns of a potential mixed GCT; hence, the current Children’s Oncology Group GCT trial mandates second surgery at the end of chemotherapy in case of incomplete response when the residual suprasellar and pineal lesion are larger than 1 or 1.5 cm, respectively.

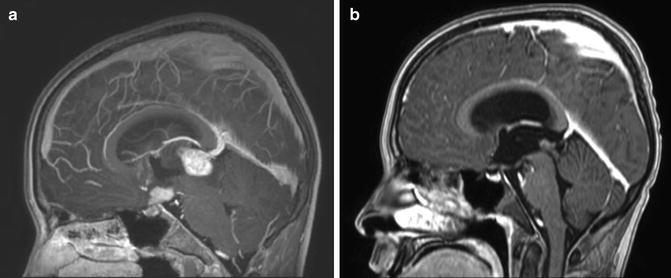

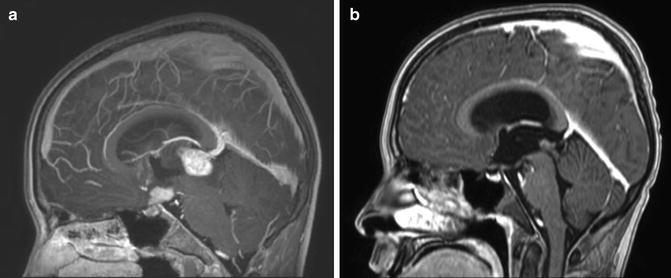

Fig. 14.2

Response to chemotherapy in a bifocal germinoma. Sagittal T1 weighted images after contrast. (a) At diagnosis. (b) After two cycles of chemotherapy with carboplatin/etoposide

Prognosis

The overall survival in germinoma surpasses 90 % either with radiation alone or with combination of chemotherapy and radiation. Current treatment strategies include pre-radiation chemotherapy in order to reduce radiation dose and volume to minimize long-term sequelae. Current evidence suggests that extent of resection does not contribute to superior outcome but may add morbidity. Hence upfront surgery should be limited to a biopsy or avoided when possible [26, 59].

Non-germinomatous Germ Cell Tumors (NGGCTs)

NGGCTs (as the name implies) represent a group of pathologies distinct from germinoma and have substantially different diagnostic factors, pathological features, different surgical/chemotherapeutic/radiation therapy approaches, and different outcomes. As such, they should be considered entirely separately from germinomas. However, germinomas and NGCCT share a common location and clinical presentation, and this presents diagnostic challenges highlighted below.

Clinical Presentation

NGGCT, like germinoma, often presents with symptoms of hydrocephalus. These can include headaches, nausea, vomiting, blurred vision or diplopia, milestone regression, gait disturbance, and in more severe presentations, drowsiness or coma. Initial clinical findings can include significant findings in the ophthalmological examination, including papilledema, sixth nerve palsy, upgaze palsy, convergence nystagmus, retractory nystagmus, and papillary response abnormalities (light-near dissociation). Although these findings are generally termed “Parinaud’s syndrome,” Parinaud himself described only the upgaze palsy [60].

Endocrinopathies can frequently be present in NGGCT, with up to 90 % of patients having at least one endocrinopathy. These can include diabetes insipidus, growth retardation, and delayed or precocious puberty particularly in males with choriocarcinoma and teratomas [61]. Accordingly, endocrinology consultation and work-up is essential at presentation.

Radiology

While radiology can be helpful in the diagnosis of NGGCT, particularly with regard to staging and guiding initial management strategies, it is important to note that there are no absolute pathognomonic radiological features. CT is very helpful in determining the presence and location of calcification and hemorrhage. While calcification of the pineal is frequently a normal finding in older children and adults, the finding of a calcified pineal in a child under 6 years of age is cause for concern, and requires further work-up for CNS-GCT [62]. Germinomas as well as NGGCT can have central or peripheral calcification. More marked calcifications can be associated with teratoma. Hemorrhage can be associated with all CNS-GCT, but choriocarcinoma in particular is associated with hemorrhagic foci.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree