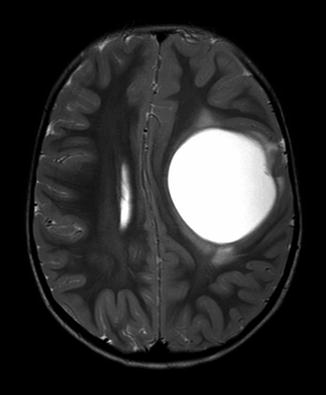

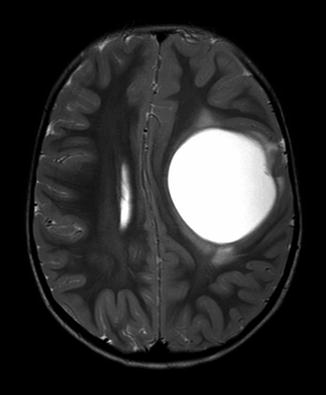

Fig. 17.1

Choroid plexus carcinoma in an infant (MRI T2-weighted image)

Pathology/Biology

Choroid plexus papillomas are classified as a WHO grade I (low-grade) tumour, while choroid plexus carcinoma is a WHO grade III (high-grade) tumour. The pathology for these tumours exists on a spectrum between papilloma and carcinoma. Cytokeratins and vimentin are expressed in both, while S-100 staining is more common in CPP than CPC. As expected, CPPs have a very low mitotic index of activity, while CPCs show obvious signs of malignancy that include high cell division, nuclear pleomorphism, and necrotic areas [2]. The higher-grade CPCs are the CNS tumours with the strongest association with the genetic cancer predisposition syndromes related to p53 mutations. Therefore, all patients with a CPC should undergo a thorough family history and screening for the presence of hallmark cancer types, such as adrenocortical carcinomas or sarcomas in young family members. When suspicion is made of a familial cancer syndrome, referral for genetic counselling and appropriate screening tests should be made. Experienced genetic counsellors are crucial as the emotional and medical consequences of having a familial cancer predisposition are extensive. If a familial pattern is found, such as the Li–Fraumeni syndrome, published guidelines have demonstrated that careful screening and early detection can impart a survival benefit [3].

Current Treatment

For choroid plexus papillomas, surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment and attempts should be made to safely achieve gross total resection. Careful observation would follow, and there is no indication for radiation or chemotherapy in the upfront treatment of this subgroup.

Surgical resection remains important for choroid plexus carcinomas but is insufficient to cure this disease, and total resection often be limited by the haemorrhagic nature of these tumours. Radiation has been used in different settings for the treatment of CPCs, with consideration of craniospinal treatment given the metastatic potential of this subgroup. This may be considered for ‘older’ children (e.g. older than 3 years), but toxicities will be very significant for the younger population. In a population-based study by the Canadian Pediatric Brain Tumour Consortium, none of the infant CPC patients had been treated with radiation over a 15-year period (median age at diagnosis was 10 months old, with the oldest being 30 months old) [4]. While a specific chemotherapy regimen has yet to be defined for CPTs, there is evidence to suggest that intensive chemotherapy plays an important role for the malignant choroid plexus carcinomas [5]. The use of ‘ICE’ chemotherapy (ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide) in the neo-adjuvant setting has allowed a second-look surgical approach to be more feasible [5]. There is an ongoing investigation into the use of direct CSF chemotherapy (intraventricular or intrathecal) for this group of patients, perhaps thought to be more effective due to the location of the choroid plexus in the ventricular space. This can technically be done via lumbar puncture or more commonly with the use of an implanted device, such as an Ommaya reservoir.

Outcome

Patients with choroid plexus papilloma have a very good survival rate overall, even in the rare cases of metastatic disease. The long-term outcome for children has generally been greater than 90 %; a study of 21 CPP patients over a 15-year period in Canada showed 100 % survival [4].

On the other hand, CPC is known to carry a relatively poor prognosis, even with aggressive therapy. Gross total resection carries a dominant influence on prognosis; 5-year survival rates are close to 60 % with complete removal, compared to 20 % with partial resection alone [6]. In the patients with an incomplete resection, chemotherapy increases to the survival in the range of 40–60 % [5] [6].

Future Directions in Choroid Plexus Tumours

The rarity and poor prognosis of choroid plexus carcinoma has created a strong interest in international collaboration over the past two decades. This is an example of using well-designed clinical trials and registry data to maximize our understanding of a very rare disease, instead of relying only upon case reports. The type, timing, and intensity of chemotherapy will continue to be explored, and the question of which patients truly need radiation therapy is still under investigation. At the same time, we need to continue to follow the choroid plexus papilloma patients to ensure that their very high survival rate holds up over time. As well, many other factors contribute to long-term neurocognitive deficits in children with choroid plexus tumours: the size of these aggressive tumours, long-standing hydrocephalus at diagnosis, and extensive or sometimes multiple surgeries. These patients should be followed closely long term and need to have access to neuropsychological testing and resources for academic rehabilitation.

Pituitary Adenomas

Several different tumour types can be localized in the suprasellar region; germ cell tumours and craniopharyngiomas are classic examples that will be discussed elsewhere in this book. As a group, tumours of the pituitary area are the most common CNS tumour type for older children in the 15–19 years age group [1]. Pituitary adenomas are one type that occur throughout adulthood and in rare circumstances occur in the postpubertal adolescence [7]. While they may have a benign histology, these tumours can be functionally harmful. Symptoms depend on the size and on hormonal secretion, with prolactinomas being the most common in children, followed by adrenocorticotropin-hormone-secreting and growth- hormone-secreting tumours [8]. Headaches, raised intracranial pressure, and visual field defects can result from any mass in this area, and elevated hormone levels will cause secondary problems (such as elevated prolactin levels leading to amenorrhoea and galactorrhoea). On neuroimaging, loss of the pituitary bright spot can provide an early sign that the pituitary stalk is being compressed. MRI may reveal a mass lesion, although adenomas can exist in both microadenoma and macroadenoma forms. Current treatment can involve surgical resection, with a transsphenoidal approach often considered. However, medical management is often needed for the endocrinopathies and may be a sufficient treatment for these tumours depending on whether other symptoms (e.g. hydrocephalus) are present. The appropriate use of dopamine agonists (bromocriptine, cabergoline) is sufficient for treating prolactinomas [9]. Once medical management is established and endocrinopathies have been addressed, overall prognosis is extremely good. Since this tumour occurs at a much greater frequency in adults than in children, this is an appropriate situation to consult adult medical oncology and surgical colleagues for advice on management strategies.

Astroblastoma

This very rare neuroepithelial glial tumour is included as an interesting CNS tumour that has been difficult to classify from a tumour grade perspective (Fig. 17.2). While the grading of rare tumours can often guide the clinician as to the best course of treatment, this is one of the few tumours listed in the WHO classification book that has not been assigned a specific grade. Although a tumour of its description was first described by Bailey and Cushing, it is felt to be ‘premature to establish a WHO grade at this time’ [2], which speaks to the rarity of its occurrence. These tumours have been reported at almost any age but typically appear in children and young adults. The imaging findings are quite striking, typically appearing as a large cystic area with a well-demarcated wall that enhances with MRI contrast. The pathology shows clear tumour margins and areas around blood vessels where tumour cells radiate outwards, anchored by cytoplasmic processes [2]. A variety of features have been described, ranging from anaplastic to a more well-differentiated form, and this information will be important for the clinician. In conjunction with the location and degree of resection, this could direct the choice for further adjuvant therapies including chemotherapy or radiotherapy. In the few literature case series and reports, a wide variety of treatment approaches have been used, including surgery alone, surgery followed by radiation, or the addition of many different chemotherapy treatments [10, 11]. Due to its rarity, a true prognosis is difficult to estimate but the limited data suggests an excellent prognosis overall.

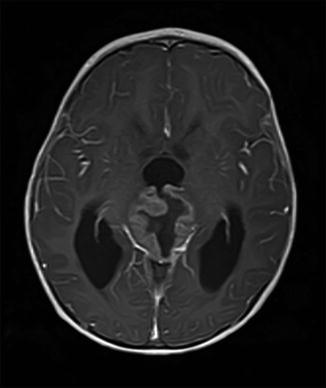

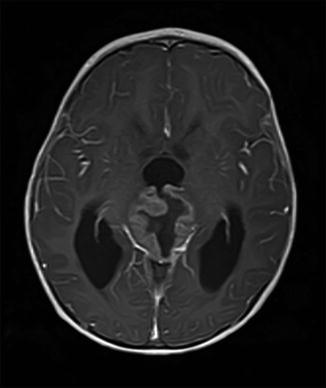

Fig. 17.2

Astroblastoma (axial MRI T2-weighted imaging)

Papillary Tumour of the Pineal Region

Most high-grade tumours presenting in the pineal region of children will turn out to be a form of primitive neuroectodermal tumour (PNET), referred to as a pineoblastoma in this location (Fig. 17.3). A much less common type is called papillary tumour of the pineal region (PTPR), which is considered to be a very rare tumour (less than 100 reported cases in the literature). This tumour serves as a reminder of how location can help define different types; there are a limited number of tumour types that will occur in this specific area, and the surgical approach may be very different between the histologies. The rarity of this tumour makes it challenging to estimate an incidence for this tumour, and case reports have described this tumour occurring in people of all ages. As with other tumours in this area, hydrocephalus is a common presenting symptom due to obstruction, and MRI is the ideal scan to define tumours in the pineal region. The MRI demonstrates a contrast-enhancing tumour with high T2 signal. Immunohistochemistry is striking for reaction to keratin stains, along with vimentin, S-100, and focal GFAP expression. The WHO grading rests between grade II and grade III; therefore, the grade does not necessarily demonstrate the exact course of treatment. Treatments reported in the literature vary from surgical resection alone, to radiation (depending on the age), to attempts at chemotherapy if there is dissemination at diagnosis (in younger children). Relapse is relatively common, leading to a progression-free survival around 25 % with an average survival rate around 75 % [12].

Fig. 17.3

High-grade papillary tumour of the pineal region (axial MRI with contrast, T1-weighted imaging)

Vestibular Schwannoma (Acoustic Neuroma)

Neurofibromatosis type I and type II are genetic syndromes that carry a predisposition for the formation of many different CNS tumours, both benign and malignant. The presence of bilateral vestibular schwannomas is one of the diagnostic criteria for neurofibromatosis type II (NF-2). This is one of the many examples of rare paediatric CNS tumours that can be linked to patients with an underlying genetic syndrome. Sometimes called ‘acoustic neuromas’, these are benign tumours arising from the 8th cranial nerve that can cause progressive hearing loss and deafness. NF-2 is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder occurring at an incidence of 1 per 25–40,000 people in the population [13]; about half of cases arise as a spontaneous mutation on chromosome 22 with no family history [14]. MRI imaging is usually performed after an acute hearing loss without other explanation, although other cranial nerves can become involved as well causing isolated deficits. Contrast-enhancing T1 imaging demonstrates these tumours well and the diagnosis can often be made on imaging, without a tissue biopsy. Vestibular schwannomas are benign tumours, so the treatment principle is typically to consider surgical resection (with an experienced skull-base neurosurgeon) or to use focal radiation. Depending on the size of the tumour, stereotactic radio-surgery may plan an important role. There has been research suggesting that medical therapy may play a role in stabilizing or even reversing the hearing loss with acoustic neuroma, for example, by targeting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors [15].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree