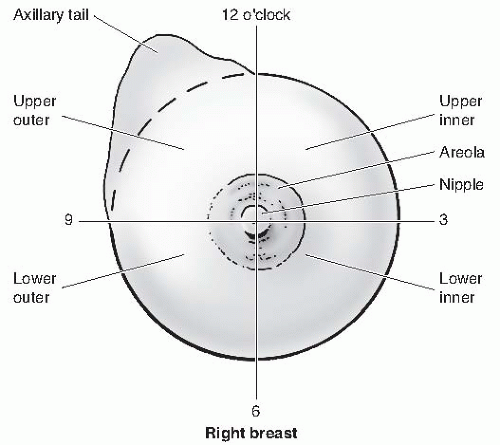

The borders of the adult breast are the second and sixth ribs in the vertical axis and the sternal edge and midaxillary line in the horizontal axis. A small portion of breast tissue also projects into the axilla, forming the axillary tail of Spence.

The breast is composed of three major tissues: skin, subcutaneous tissue, and breast tissue. The breast tissue, in turn, consists of parenchyma and stroma. The parenchyma is divided into 15 to 20 segments that converge at the nipple in a radial arrangement. There are between 5 and 10 collecting ducts that open into the nipple. Each duct gives rise to buds that form 15 to 20 lobules, and each lobule consists of 10 to 100 alveoli, which constitute the gland.

The breast is enveloped by fascial tissue. The superficial pectoral fascia envelops the breast and is continuous with the superficial abdominal fascia of Camper. The undersurface of the breast lies on the deep pectoral fascia, covering the pectoralis major and serratus anterior muscles. Connecting the two fascial layers are fibrous bands (Cooper suspensory ligaments) that are the natural support of the breast.

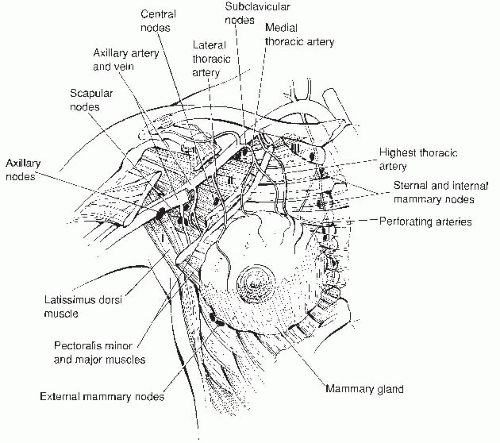

The principal blood supply to the breast is the internal mammary artery, constituting two thirds of the total blood supply. The additional third, which supplies primarily the upper outer quadrant, is provided by the lateral thoracic artery. Nearly all of the lymphatic drainage of the breast is to the axillary nodes. The internal mammary nodes also receive drainage from all quadrants of the breast and are an unusual, but potential, site of metastasis.

The majority of abnormalities in the breast that result in biopsy are due to benign breast disease. Benign abnormalities can result in pain, a mass, calcifications, and nipple discharge. Similar findings can be present in malignant disease.

For the purposes of delineating metastatic progression, the axillary lymph nodes are categorized into levels. Level I lymph nodes lie lateral to the outer border of the pectoralis minor muscle, level II nodes lie behind the pectoralis minor muscle, and level III nodes are located medial to the medial border of the pectoralis minor muscle.

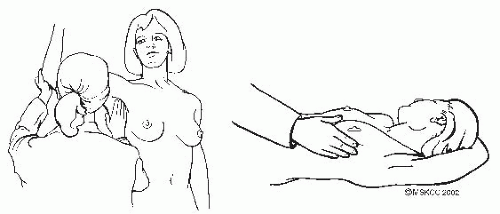

The clinical breast examination (CBE) should be part of the gynecologic examination (Fig. 2-2) and is best for detecting tumors greater than 2 cm in size. The National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program found that CBE detects approximately 5% of cancers that are not visible on mammography. Also, it offers an opportunity to demonstrate the technique of breast self-examination and to encourage women to perform this examination on a regular basis. The examination consists of:

TABLE 2-1 Breast Cancer Screening Techniques and Guidelines

Application

Sensitivity/Efficacy

Limitations

Guidelinesa

Mammography

Detects microcalcifications, abnormal shadowing, or soft tissue distortion

Sensitivity 74%-95%

Specificity 89%-99%

Sensitivity is decreased in women younger than age 50 years and in women with dense breasts.

Reduces risk of cancer-related mortality by 16%-35%

Less sensitive for faster growing tumors (young women)

Breast density

Hormone therapy

Breast implants

USPSTF: ≥50-74, every 2 years

ACOG: 40-49, every 1-2 years, then ≥50-75 years, annually

ACS: 40-69, annually

NCI: ≥40, every 1-2 years

Clinical breast exam

Inspection and palpation in the supine and sitting positions, including axillary and supraclavicular lymph nodes as well as nipple and areola

Recommended 6-10 min

Sensitivity 54%

Specificity 94%

Detects approximately 5% of cancers missed by mammography

Most studies show efficiency in conjunction with mammography— likely that each contributes

Examiner dependent

Less specificity than mammography— higher rate of biopsy for benign disease

Limited in obese women

USPSTF: insufficient evidence

ACOG: 20-39, every 1-3 years, then annually

ACS: 20-39, every 3 years, then annually

Breast selfexamination

Monthly exams, during approximately 10th day of cycle

Sensitivity 20%-30%

Very few randomized trails

Failed to show benefit in rate of diagnosis, cancer death, or tumor size

Examiner dependent

Higher rate of biopsy for benign disease

Studies limited

USPSTF: do not support teaching self-breast exams

ACS: Inform women regarding benefits and limitations.

ACOG: supports selfbreast awareness

Screening recommendations differ for patients with a family or personal history of breast cancer.

a A summary of guidelines can be found at the National Guideline Clearinghouse. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov.

USPSTF, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; ACOG, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; ACS, American Cancer Society; NCI, National Cancer Institute.

Inspection and palpation of the breasts in the supine and sitting positions, with hands above the head and then on the hips. The supine position flattens the breast tissue against the chest, allowing for a more thorough exam.

Observation of the contour, symmetry, and vascular pattern of the breasts for signs of skin retraction, edema, or erythema in each of the previously mentioned positions

Systematic palpation of each breast, the axilla, and supraclavicular areas in a circular motion using light, medium, and deep pressures. Use the pads of the three middle fingers to palpate for masses. A vertical strip pattern appears more thorough than concentric circles. To ensure that all breast tissue is examined, cover a rectangular area bordered superiorly by the clavicle, laterally by the midaxillary line, and inferiorly by the bra line.

Evaluation for nipple discharge, crusting, or ulceration

For the anatomic location and description of tumors or disease, the surface of the breast is divided into four quadrants and the numbers of the face of a clock are used as reference points (Fig. 2-3). A finding may be described as “a hard mass palpated in the upper inner quadrant of the right breast at the 2 o’clock position, approximately 2 cm from the nipple.”

The clinical use of breast self-examination is controversial (see Table 2-1). Breast self-awareness is a woman’s awareness of the normal appearance and feel of her breasts and may or may not include breast self-examination. She is encouraged to discuss any changes in her breasts with her health care provider.

Although mammography remains the primary screening modality for breast cancer, <40% of women actually undergo annual mammography. Breast cancers detected by mammography tend to be smaller and have more favorable histologic and biologic features. Limitations to mammography include patient age, rate of tumor growth, density of breast tissue, use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT), and breast implants. Approximately 5% to 15% of cancers are not apparent on mammography, and all palpable lesions require biopsy.

Screening mammography is for women with no signs or symptoms of breast disease and consists of bilateral two-view images. Mammography can potentially detect lesions as small as 1 mm. Digital mammography is more effective than film mammography, especially for women younger than 60 years or with dense breasts.

Diagnostic mammography presents various views (e.g., spot compression, magnification) and localization techniques and is usually used after the discovery of an abnormal finding on clinical exam, self-exam, or screening mammography. Mammography is an essential part of the evaluation of a patient with clinically evident breast cancer. In this situation, mammography is useful for evaluating other areas of the breast as well as the contralateral breast.

Suspicious radiologic findings require surgical consultation and consideration of breast biopsy, even with an unremarkable physical examination.

Radiologic findings of concern on mammography:

Soft tissue density, especially if borders are not well defined

Clustered microcalcifications in one area

Calcification within or closely associated with a soft tissue density

Asymmetric density or parenchymal distortion

New abnormality compared with previous mammogram

When a woman’s screening mammography is ambiguous, diagnostic mammography should be performed with possible radiographically directed biopsy. Biopsy

techniques for radiographically identified nonpalpable lesions include needle localization, excisional biopsy, and stereotactic core biopsy. If the mammographic studies are inconclusive, a short-term follow-up study at 3 to 6 months can be considered (Table 2-2).

TABLE 2-2 American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System Mammography Assessment Categories | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ultrasound: Although ultrasound is not a substitute for mammography, it has become a common tool in the evaluation of breast lesions. Ultrasound is particularly useful in differentiating cystic from solid lesions and is most commonly used

in evaluating lesions in young women, especially those younger than age 40 years. It can also be used as an adjunctive screening tool in women with dense or cystic breasts or those with breast implants. Suspicious features include solid masses with ill-defined borders, acoustic shadowing, or complex cystic lesions. Ultrasound guidance also assists in diagnostic procedures, including biopsy or fine-needle aspiration.

MRI has been shown in studies to be more sensitive but less specific and more expensive than mammography in the detection of breast cancers.

MRI screening is recommended for women with a greater than 20% lifetime risk of developing breast cancer. These include women with known BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, first-degree relatives of those with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations who have not undergone genetic testing, history of radiation therapy to the chest between ages 10 and 30 years, women with certain genetic syndromes (including Li-Fraumeni and Cowden syndromes), or a first-degree relative with one of those syndromes.

MRI screening is not recommended for women at average risk of developing breast cancer.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree