Anatomy of the Female Pelvis

Lauren Owens

Isabel Green

ABDOMINAL WALL

The anterior abdominal wall lies ventrally and is outlined superiorly by the lower edge of the rib cage; caudally by the iliac crests, inguinal ligaments, and pubic bone; and dorsolaterally by the lumbar spine and adjacent muscles.

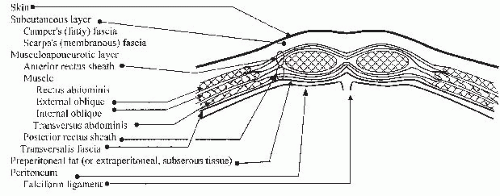

Layers of the Anterior Abdominal Wall

Skin

Subcutaneous layer: This consists of fat globules in a meshwork of fibrous septa. Camper fascia is the more superficial aspect of the subcutaneous layer.

Scarpa fascia is the deeper portion and has a more organized consistency than Camper fascia secondary to more fibrous tissue.

Musculoaponeurotic layer: Located immediately below the subcutaneum, the musculoaponeurotic layer consists of layers of fibrous tissue and muscles that hold the abdominal viscera in place.

Rectus sheath: The aponeuroses of the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles comprise the rectus sheath.

The anterior rectus sheath is anatomically different above and below the arcuate line. The arcuate line (linea semicircularis, semilunar fold of Douglas) is located midway between the umbilicus and symphysis pubis. It marks the lower edge of the posterior rectus sheath.

Above the arcuate line, the anterior rectus sheath is composed of the aponeuroses of the external oblique and ventral half of the internal oblique muscles. The posterior rectus sheath is composed of the aponeuroses of the dorsal half of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles (Fig. 26-1).

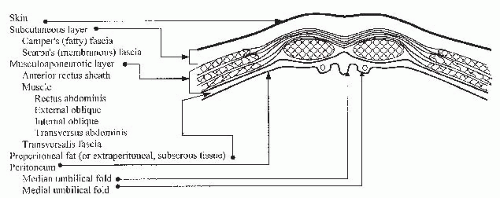

Below the arcuate line, the anterior rectus sheath is composed of the aponeuroses of all the muscles previously mentioned (Fig. 26-2).

The linea alba is the midline between the rectus abdominis muscles. Above the arcuate line, the linea alba marks the fusion of the anterior and posterior rectus sheaths.

Abdominal wall muscles

Oblique flank muscles lie lateral to the rectus abdominis muscles.

The external oblique muscle originates from the lower eight ribs and iliac crest and runs obliquely, anteriorly, and inferiorly.

The internal oblique muscle originates from the anterior two thirds of the iliac crest, the lateral part of the inguinal ligament, and the thoracolumbar fascia in the lower posterior flank. It runs obliquely, anteriorly, and superiorly.

The transversus abdominis muscle runs transversely, originating from the lower six costal cartilages, the thoracolumbar fascia, the anterior three fourths of the iliac crest, and the lateral inguinal ligament. The nerves and vasculature of the flank are found between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles and, therefore, are susceptible to injury in transverse incisions.

Longitudinal muscles

The rectus abdominis muscle is a paired muscle, found on either side of the midline, originating from the sternum and cartilage of ribs 5 through 7 and inserting into the anterior surface of the pubic bone.

The pyramidalis muscle is a vestigial muscle with a variable presence among individuals. It arises from the pubic bone and inserts into the linea alba several centimeters cephalad to the symphysis ventral to the rectus abdominis muscle.

The transversalis fascia is a layer of fibrous tissue, located underneath the abdominal wall muscles and outside the peritoneum. The transversalis is separated from the peritoneum by a variable layer of adipose tissue.

Peritoneum: A single layer of serosa lines the posterior aspect of the anterior abdominal wall. Five vertical folds converge toward the umbilicus.

The median umbilical fold is a single fold created by the median umbilical ligament or obliterated urachus.

The apex of the bladder blends into the median umbilical ligament and is highest in the midline. This relationship should be considered when entering the peritoneal cavity.

The medial umbilical folds are paired folds lateral to the median umbilical fold, remnants of the obliterated umbilical arteries; they converge at the umbilicus.

The lateral umbilical folds are paired folds caused by the inferior epigastric vessels.

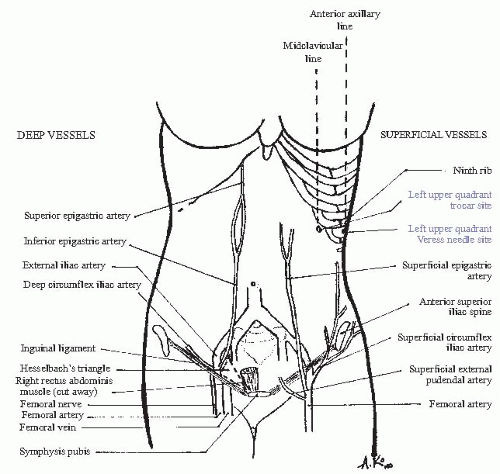

Vasculature of the Abdominal Wall

Subcutaneous vascular supply (Fig. 26-3)

The superficial epigastric artery branches from the femoral artery after it descends through the femoral canal. It runs superomedially, approximately 5 cm lateral to the midline.

The superficial circumflex iliac artery branches from the femoral artery and runs laterally toward the flank.

Musculofascial blood supply parallels the subcutaneous supply (see Fig. 26-3).

The inferior epigastric artery branches from the external iliac artery, proximal to the inguinal ligament. It runs cephalad, deep to the transversalis fascia and lateral to the rectus muscle. Midway between the pubis and umbilicus, the vessels intersect the lateral border of the rectus muscle and course between the dorsal aspect of the rectus and the posterior rectus sheath. These vessels run between 4 and 8 cm lateral to the midline. After entering the posterior rectus sheath, numerous branches supply all layers of the abdominal wall and anastomose with the superior epigastric vessels.

The superior epigastric artery branches from the internal thoracic artery and runs caudally to form anastomoses with the inferior epigastric artery.

The deep circumflex iliac artery also branches from the external iliac artery and runs laterally between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles.

Abdominal Wall Incisions

Vertical: A midline incision provides optimal exposure to the abdomen. The incision is made from the symphysis to below the umbilicus, depending on how much space is needed. A small incision or “mini-lap” may offer excellent visualization and improved cosmesis. The incision can always be extended more cephalad and then circumferentially around the umbilicus to the left to avoid the ligamentum teres. The anterior rectus sheath is incised longitudinally. The peritoneum is entered taking care to avoid the superior aspect of the bladder.

Pfannenstiel incision: This is one of the most common incisions in obstetrics and gynecology. A transverse incision is made approximately two fingerbreadths (3 to 4 cm) above the pubic symphysis. Transverse incisions are generally less painful and more cosmetic than longitudinal incisions as they run along Langer lines. The incision is continued through the rectus sheath, and then the rectus muscles are dissected cephalad and caudad off the posterior aspect of the rectus sheath. Then, the rectus muscles are separated in the midline to gain entry to the peritoneum through a midline longitudinal incision. The degree of separation of the rectus

fascia from the underlying rectus muscles determines the amount of exposure provided by the Pfannenstiel incision. If more space is needed, the rectus fascia can be separated from the rectus muscle up to the umbilicus. Lateral extension of the skin incision runs a greater risk of injury to the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves either by direct incision or more often by entrapment during fascial closure.

Cherney incision: A modification of the Pfannenstiel incision, the Cherney incision provides better exposure to the pelvis than the Pfannenstiel. After the rectus muscle is dissected off the fascia, as in a Pfannenstiel, the tendinous insertion of the rectus muscle is cut approximately 0.5 cm above the insertion site at the posterior aspect of the pubic bones. The rectus bellies are then moved cephalad, providing excellent exposure to the pelvis. Note the importance of leaving enough tendons on the pubic bone so that the caudal aspect of the rectus muscles can be reapproximated to the tendon with a delayed absorbable suture in a horizontal mattress fashion during closure.

Maylard incision: The Maylard incision provides the best pelvic exposure of all the incision types. This incision is transverse, like the Pfannenstiel, with two main differences. The Maylard incision is made slightly more cephalad (at the level of the anterior superior iliac spine), and the rectus muscles are not dissected off the fascia. Rather, they are left attached to the rectus sheath and the muscles are transected. The inferior epigastric vessels are identified and ligated before the rectus muscles are transected completely. This helps to prevent blood loss from inadvertent inferior epigastric injury and also serves to preserve blood supply. This type of incision has the potential for greater blood loss but also for better pelvic exposure.

Abdominal Landmarks for Laparoscopy

Primary laparoscopic trocars are placed for initial access. In gynecology, these are most often placed at the umbilicus or in the left upper quadrant. Accessory trocars may be placed suprapubically or laterally (see Fig. 26-3).

Umbilical trocar: The umbilical trocar should be placed at a 45-degree angle in thin women in order to avoid hitting the aorta or common iliacs. In an obese patient, the trocar can be placed at a more perpendicular angle due to the amount of adipose tissue that must be traversed.

Left upper quadrant trocar: A trocar may be placed at Palmer point, 3 cm below the left costal margin in the midclavicular line. Prior to trocar insertion, the stomach should be emptied with a nasogastric tube. This location is preferred in patients with prior midline surgery to avoid potential visceral adhesions.

Suprapubic trocar: The suprapubic trocar is placed two fingerbreadths above the pubic symphysis. It is placed under direct visualization and after Foley insertion in order to assure that the bladder is not in line of the trocar path.

Lateral trocars: The lateral trocars are placed at least 5 cm cephalad to the pubic symphysis and 8 cm lateral to the midline in order to avoid the inferior epigastric vessels. The trocar is placed under direct visualization lateral to the lateral umbilical folds to avoid injury to the inferior epigastric vessels.

PELVIC VISCERA

Vagina

The vagina is shaped like a flattened tube, starting at the distal hymenal ring and ending at the fornices surrounding the proximal cervix. Its average length is 8 cm; this varies greatly with age, parity, and surgical history.

The vaginal epithelium is nonkeratinized, stratified squamous epithelium lacking mucous glands and hair follicles.

Deep to the epithelium is the vaginal muscularis or endopelvic fascia. The term fascia is misleading because this is actually fibromuscular tissue that includes fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, and elastin, in addition to type I and III collagen, all loosely arrayed to create an elastic supportive layer. At the vaginal apex, this fibromuscular layer coalesces to create the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments. The fanshaped cardinal ligament creates a sheath that envelops the uterine artery and vein, fusing medially with the paracervical ring. The uterosacral portion inserts into the posterior and lateral aspect of the paracervical ring and then curves laterally along the pelvic sidewall to attach to the presacral fascia that overlies the second, third, and fourth sacral vertebrae. Together, the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments pull the vagina proximally toward the sacrum, suspending it over the muscular levator plate.

The endopelvic fascias of the anterior and posterior vaginal wall are known as the pubocervical fascia and rectovaginal fascia, respectively. Again, these layers are not true fasciae but composed of fibromuscular sheets. Superiorly, the pubocervical fascia attaches to the cervix and the cardinal/uterosacral support of the vaginal apex. Laterally, it coalesces with the fascia of the obturator internus muscle to create the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis (ATFP) or “white line.” Inferiorly, it attaches to the pubic symphysis. The rectovaginal fascia in the upper vagina coalesces with the lateral support of the anterior vaginal wall and fuses with the ATFP. The lower half of the rectovaginal fascia fuses with the aponeurosis of the levator ani muscles along a line referred to as the arcus tendineus fascia rectovaginalis. At its most inferior point, the rectovaginal septum fuses with the perineal body (Fig. 26-4).

Uterus

The uterus is a fibromuscular organ composed of the corpus and the cervix.

Corpus: The endometrium is the innermost lining of the uterus made up of columnar epithelium and specialized stroma. The superficial layer of the endometrium contains hormonally sensitive spiral arterioles, which shed with each cycle. The myometrium contains interlacing smooth muscle fibers, and the serosal surface of the uterus is formed by peritoneal mesothelium. The fundus is the portion of the uterus cephalad to the endometrial cavity. The cornua are located where the fallopian tubes insert into the uterine cavity, lateral to the fundus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree