Fig. 27.1

ESHRE/ESGE classification of bicorporeal uterus and its variants: partial (Class U3a), complete (Class U3b), bicorporeal septate (Class U3c), complete bicorporeal with septate cervix (Class U3bC1), complete bicorporeal with double cervix (Class U3bC2, former AFS didelphys), complete bicorporeal with unilateral cervical aplasia (Class U3bC3) and complete bicorporeal with double cervix and longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum (Class U3bC2V2)

(a)

Class U3a or partial bicorporeal uterus, which is characterized by an external fundal indentation partially dividing the uterine corpus above the level of the cervix.

(b)

Class U3b or complete bicorporeal uterus, which is characterized by an external fundal indentation completely dividing the uterine corpus up to the level of the cervix; patients with complete bicorporeal uterus (Class U3b) could have or not coexistent cervical (e.g. double cervix formerly didelphys uterus-U3bC2) and/or vaginal defects (e.g. obstructing or not vaginal septum).

(c)

Class U3c or bicorporeal septate uterus, which is characterized by the presence of an absorption defect in addition to the main fusion defect. In patients with bicorporeal septate uterus (Class U3c) the width of the midline fundal indentation exceeds >150 % the uterine wall thickness.

The true incidence of female congenital malformations is unknown. The use of diagnostic methods with different accuracy, the subjectivity in the criteria used for diagnosis and classification of the anomalies and the drawbacks of the existing classification systems represent the main biases for that [20, 41]. Moreover, in some studies the population was not representative whereas the existence of undiagnosed cases is another potential bias, as many of the patients with malformations may be asymptomatic without ever reporting any gynaecological or reproductive problem.

Reports in the literature estimate that the incidence of female genital anomalies in general population varies between 4.3 and 6.7 %, while in women with fertility problems between 3.4 and 10.8 %. In patients that suffer from recurrent miscarriages, congenital anomalies are reported to range between 12.6 and 18.2 % [19, 41]. In a more recent review of 94 observational studies comprising 89.861 women, the prevalence of uterine anomalies diagnosed by optimal tests (investigations that are capable of accurately identifying and classifying congenital uterine anomalies accurately) was found to be 5.5 % [95 % confidence interval (CI), 3.5–8.5] in the general/unselected population, 8.0 % (95 % CI, 5.3–12) in infertile women, 13.3 % (95 % CI, 8.9–20.0) in those with a history of miscarriage and 24.5 % (95 % CI, 18.3–32.8) in those with miscarriage and infertility [10].

Bicornuate uteri, which are uncommon in the unselected population (0.4 %; 95 % CI, 0.2–0.6), are significantly more prevalent in women with infertility (1.1 %; 95 % CI, 0.6–2.0, P = 0.032) and those with miscarriage (2.1 %; 95 % CI, 1.4–3, P < 0.001), particularly if these coexist (4.7 %; 95 % CI, 2.9–7.6, P < 0.001) [10]. The prevalence of uterus didelphys was 0.3 % (95 % CI, 0.1–0.6) in the unselected population. This anomaly is no more prevalent in women with infertility (0.3 %; 95 % CI, 0.2–0.5), or in women with a history of miscarriage (0.6 %; 95 % CI, 0.3–1.4), but is significantly more common in infertile women with miscarriage (2.1 %; 95 % CI, 1.4–3.2, P < 0.001) [10].

Obstetric Outcome in Bicorporeal Uterus

Class U3 and U3bC2 (bicornuate and didelphys uterus), do not appear to reduce fertility but are associated with aberrant outcomes throughout the course of pregnancy, that depend on the type of the congenital anomaly. Generally women with bicornuate uterus have an increased risk of miscarriage (both first and second trimester), preterm birth and fetal malpresentation at birth, while women with uterus didelphys seem to have only a modestly increased risk of preterm labor and malpresentation at delivery [11, 19]. Uterine anomalies have been also associated with an increased incidence of placental abruption, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), prematurity, operative delivery, retained placenta and fetal mortality [37]. Obstetrical outcomes are generally reported to be better in cases of bicornuate uterus than in unicornuate uterus, perhaps given the significant variation in bicornuate uterine anatomy, subtypes of which involve a partially fused central uterine cavity [36, 38].

The cause of adverse obstetrical outcomes may be secondary to abnormal uterine vasculature, decreased cervical connective tissue and decreased uterine musculature [38]. Disturbance in the uterine blood flow, caused by absent or abnormal uterine or ovarian vessels, could potentially explain the IUGR and increased rates of spontaneous abortions [8]. Abnormal ratio of muscle fibres to connective tissue in uterine cervices is associated with abnormal müllerian development [7, 40]. Also decreased uterine musculature gestational capacity is said to be jeopardised by the presence of only half the full complement of uterine Musculature. Usually the myometrium of congenitally abnormal uteri are thinner than normal and mural thickness diminishes as gestation advances, causing inconsistencies over different aspects of the uterus [30, 31, 38]

Surgical Management of Bicorporeal Uterus

Whether surgical correction for a bicornuate uterus is necessary is controversial although it may be indicated for patients with repeatedly poor fertility outcomes in who other causes have been excluded [26]. Prerequisites are the proper classification, the clear surgical indications and the feasibility and safety features of the procedure.

The Strassman metroplasty is the traditional surgical correction for both bicornuate and didelphic uteri, currently bicorporeal uterus (Fig. 27.2a–e). The Strassman procedure essentially involves the unification of two endometrial cavities of an otherwise divided uterus. A single longitudinal incision from one cornua to the other is made into the endometrial cavity. Retracting the cornua laterally with right angle clamps, each horn of the uterus will evert and a single layer of interrupted figure-of-eight sutures beginning on the anterior uterine wall are placed transversely to form a single uterine cavity. Serosal stitches are placed in a fashion similar to a myomectomy [26, 44]. Resection of a vaginal septum associated with uterine didelphys should be undertaken if associated with obstruction, dyspareunia or infertility. The Strassman procedure has been used to reconstruct the bicornuate uterus [39]. In an uncontrolled study of 289 women with bicornuate uteri and history of previous preterm loss, the fetal loss rate was approximately 70 %. After surgery, the live birth rate significantly improved to 85 % [45]. Further studies concluded that abdominal metroplasty serves as a viable treatment modality to improve obstetric outcomes [27, 34]. In a total of 22 patients after abdominal metroplasty, 88 % of pregnancies ended with the birth of a viable infant [27]. In another study after metroplasty the fetal survival rate was 81 % in the recurrent miscarriage group and 92.8 % in the infertile group of patients [34].

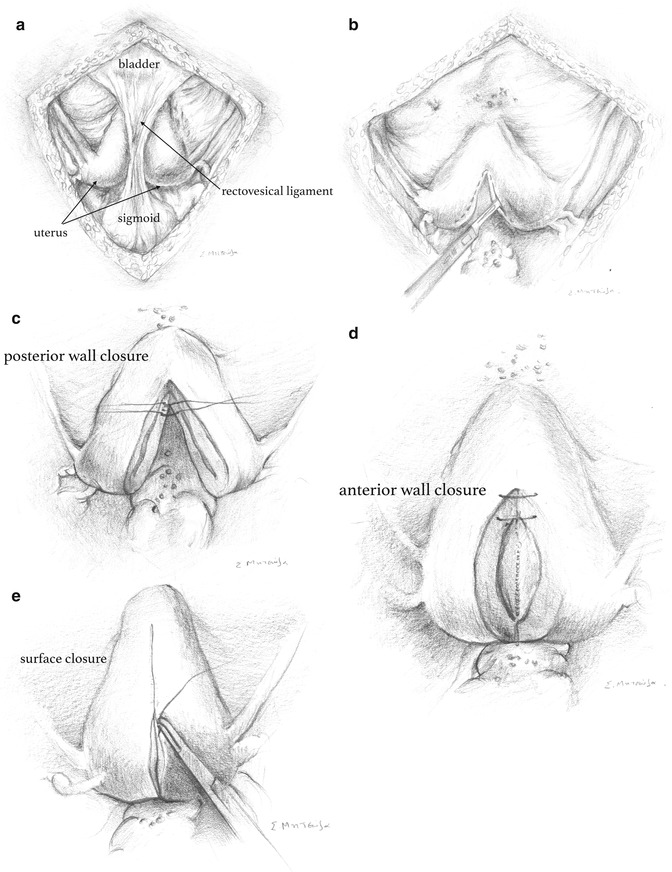

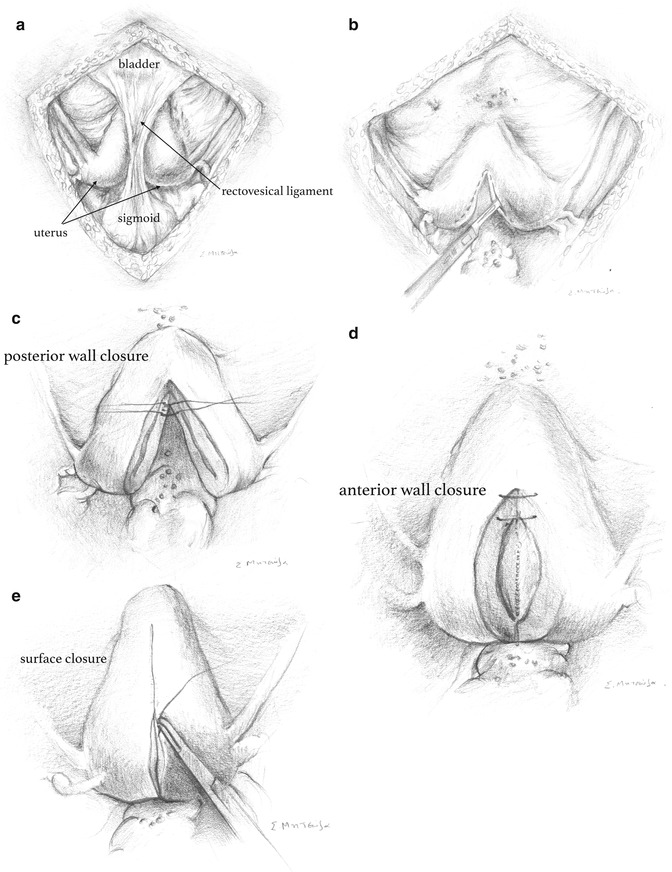

Fig. 27.2

Strassmann procedure: surgical steps. (a) bicorporeal uterus (b) incision from one cornua to the other (c) posterior uterine wall closure (d) anterior uterine wall closure (e) serosal closure

Recently, laparoscopic unification in cases of ESHRE/ESGE U3bC2 (complete bicorporeal with double cervix, formerly AFS didelphys) and U3bC0 (complete bicorporeal with normal cervix) uteri has been reported in the literature [4, 29, 35, 42]. The first laparoscopic metroplasty was reported to be a safe and successful surgical option [42]. It was followed by other case reports and case series showing good restoration of the uterine anatomy, minimal peritoneal adhesions, less blood loss, creation of a spacious uniform uterine cavity, shorter hospital stay and good scar integrity [4, 29, 35].

Strassmann metroplasty is technically quite challenging when performed by endoscopic means and good surgical skills are needed. The same surgical principles as abdominal metroplasty apply. The surgeons must be experienced laparoscopists to perform such procedures [4, 42]. The pregnancy outcomes after endoscopic metroplasty should be evaluated in large prospective trials to prove the obstetric benefit of the procedure.

Metroplasty at the time of diagnosis for patients with primary infertility is not recommended, given that fertility rates are not significantly reduced from the norm and successful pregnancies without intervention are common [11, 19, 38]. Patients should be counseled regarding the need for subsequent cesarean section, given the significant risk of uterine rupture during labour after such procedures [38].

The necessity to perform cervical cerclage is addressed. Cervical incompetence is an issue with uterine malformations, especially with the bicornuate uterus [18]. Because of this potential association, a study was performed using limited prophylactic cervical cerclage in patients with bicornuate uteri (ESHRE/ESGE class U3C0) and comparing fetal survival rate before cerclage to that after cerclage in the same subjects. Fetal survival improved from 21 to 62 % [1]. Further trials are needed to evaluate whether the cerclage is beneficial after metroplasty. It is also not clear at which week of pregnancy it should be performed.

In many cases major congenital uterine anomalies present a management dilemma in women who are symptomatic due to menorrhagia and not responsive to medical therapy. It was reported that the incidence of uterine malformations in women presenting with abnormal uterine bleeding was 19/322 (5.9 %) [28]. In these cases surgical management appears to be the best option and given the established safety of laparoscopic procedure for removal of morphologically normal uteri, it was considered to be a suitable alternative treatment option in a case of didelphys uterus (ESHRE/ESGE class U3bC2). Erian et al. [16] performed a day-case laparoscopic subtotal hysterectomy in a woman with U3bC2 uterus and menorrhagia [16]. Technically, the procedure was similar to laparoscopic subtotal hysterectomy performed in morphologically normal uteri [15]. The most significant difference was the separate removal of the two uterine corpora using two lap loop systems sequentially [16]. It should be noted that surgical identification of the ureters is essential part of the surgery as urinary tract anomalies are frequent in women with uterine congenital malformations [16, 23].

Surgical Management of Bicorporeal Uterus Variants

Depending on the anatomical status of cervix and/or vagina, bicorporeal uterus could be presented in some not very common variants (Fig. 27.1); Fedele et al. [17] in an interesting epidemiological study of 87 patients with bicorporeal or septate (“double”) uterus, unilateral cervico-vaginal obstruction and ipsilateral renal anomalies have examined all the anatomic variants and their relative frequency. In 67 out of 87 cases a didelphys uterus was found; in 63 cases with a concomitant longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum (complete bicorporeal uterus with double cervix and longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum – ESHRE/ESGE Class U3bC2V2) and in 4 patients with unilateral cervical aplasia (complete bicorporeal uterus with unilateral cervical aplasia – ESHRE/ESGE Class U3bC3V0). Furthermore, in 10 cases a bicornuate uterus was diagnosed; in 9 patients with double cervix and longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum (partial bicorporeal uterus with double cervix and longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum – ESHRE/ESGE Class U3aC2V2) and in 1 patient with septate cervix and longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum (partial bicorporeal uterus with septate cervix and longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum – ESHRE/ESGE Class U3aC1V2). Didelphys uterus with longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum and ipsilateral renal agenesis is known also as Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich or OHVIRA syndrome [12, 24, 43, 47]. In all these variants the existing obstruction is the main indication for surgical treatment.

Bicorporeal Uterus with Unilateral Cervical Aplasia (ESHRE/ESGE Class U3bC3)

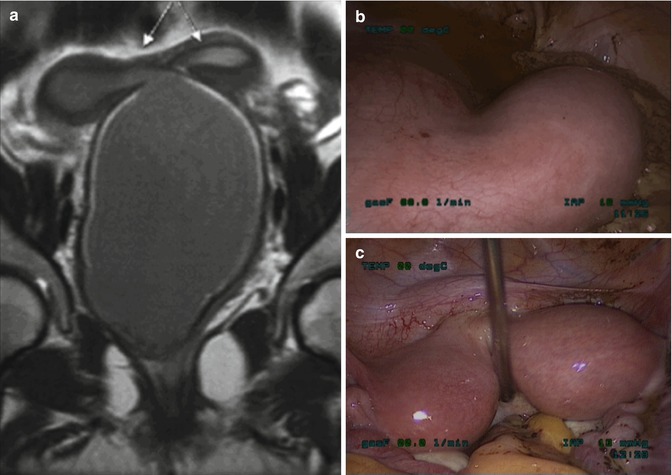

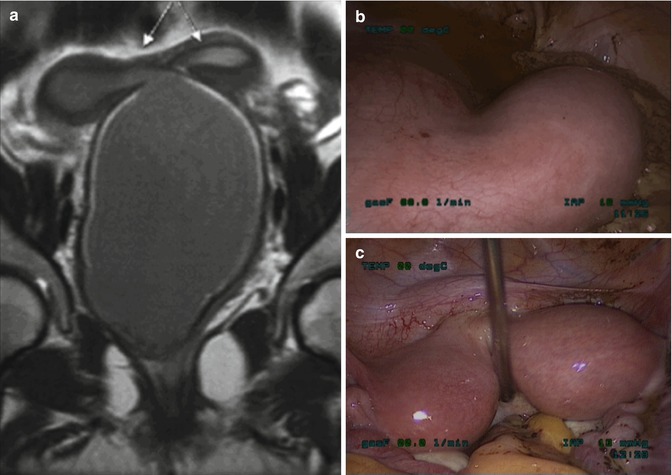

Surgical treatment is necessary and laparoscopic management feasible in these rare subclasses of bicorporeal uterus, which present with obstructing symptoms other than fertility (Fig. 27.3). Removal of the obstructed side of the uterus is the indicated treatment; successful laparoscopic removal followed by morcellation of the obstructed part of a didelphys uterus with unilateral cervical and renal aplasia (ESHRE/ESGE Class U3bC3) has been already reported [5].

Fig. 27.3

Complete bicorporeal uterus with double cervix and longitudinal obstructing vaginal septum (ESHRE/ESGE Class U3bC2V2): (a) MRI image showing the presence of RT hemi-hematometra, RT hemi-hematocolpos and LT side normal, (b) Laparoscopic view showing the RT obstructed hemi-uterus and the RT hemi-hematocolpos and (c) Laparoscopic view after incision of the vaginal septum showing the two sides of the uterus

It should be noted that in such cases the hemi-uterus might act clinically as rudimentary horn and the risk for a pregnancy is possible; the only difference between a rudimentary horn and a hemi-uterus with cervical aplasia is the presence of uterine isthmus in cases of hemi-uterus. Pregnancy in an obstructed part of a didelphys uterus must be treated, as one would do with any other ectopic pregnancy and this could be done by minimal access surgery [32]. Furthermore, it seems reasonable that an obstructed hemi-uterus should be removed in symptom-free patients as soon as diagnosis is made to avoid potential complications and surgical removal during pregnancy [32].

Restoration of utero-vagina continuity of the obstructed hemi-uterus has been also proposed as an alternative either by laparoscopically assisted cervicoplasty in cases of cervical atresia or by isthmo-vagina anastomosis [17]. However, it should be offered in patients after proper counseling and understanding of its potential complications, especially ectopic pregnancy. Written consent is essential prior to these procedures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree