FIGURE 49-1 Anteroposterior radiograph of the proximal humerus depicting a pathologic fracture through a UBC. Note is made of the characteristic “fallen fragment” sign.

CLINICAL QUESTIONS

- What is a unicameral bone cyst (UBC)?

- What is an aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC)? How does it differ from a UBC?

- What is the risk of malignant transformation with these lesions?

- What are the treatment options for UBCs and ABCs?

- What are the complications from treatment?

- What are the indications and techniques for deformity correction and limb lengthening following proximal humeral physeal disturbance?

- What are the treatment principles and techniques for other common benign tumors of the pediatric upper limb?

THE FUNDAMENTALS

The pediatric hand and upper extremity surgeon will encounter a host of benign tumors of the upper limb. While benign, unicameral bone cysts (UBCs) and aneurysmal bone cysts (ABCs) may cause pain, pathologic fracture, progressive deformity, and/or limb length difference. Other common lesions—including giant cell tumor of tendon sheath, enchondroma, and infantile fibroma, among others—may similarly become symptomatic or cause functionally limiting deformity. Understanding of the principles of treatment and techniques of surgical care will allow for optimization of management and minimization of complications.

Etiology and Epidemiology

Although the exact incidence is unknown, benign tumors of the upper limb are common in children and frequently present to the pediatric hand surgeon for diagnosis and treatment. In a prior retrospective review of 349 children presenting at a tertiary care pediatric hospital for evaluation of a hand or wrist “tumor,” the most common diagnoses were retained foreign bodies, ganglion cysts of the wrist, and retinacular cysts of the digits1 (Table 49.1). Other common entities included vascular (most commonly venous) malformations, epidermal inclusion cysts, and enchondromas. Malignant tumors accounted for 2% or less of all lesions, reinforcing the concept that malignancies of the pediatric hand are quite uncommon. While the differential diagnosis in the evaluation of a benign-appearing mass is quite broad, each will have its own set of characteristic clinical and radiographic features, which help make the diagnosis and guide treatment.

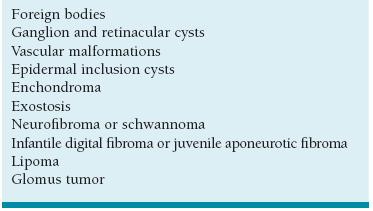

Table 49.1 Common benign tumors of the pediatric hand and upper limb

Adapted from Colon F, Upton J. Pediatric hand tumors. A review of 349 cases. Hand Clin. 1995;11:223–243.

In addition to these benign entities, bone cysts are frequently encountered in the growing upper limb. UBCs refer to fluid-filled lesions that commonly affect the metaphysis of long bones in children and adolescents.2–4 There is a roughly 2:1 male:female predisposition, and the vast majority of patients will be <20 years of age. Also known as simple bone cysts, the exact prevalence of UBCs is unknown, as many are asymptomatic and therefore never identified or diagnosed. They are thought to comprise 3% of all biopsied primary bone tumors and may be the most common cause of pathologic fractures of the long bones.2,5–7

The precise etiology of UBCs has yet to be characterized. Some investigators have proposed that UBCs represent intraosseous synovial cysts, based upon electron microscopy.8 Others have suggested that UBCs are a result of interstitial fluid accumulation in the setting of abnormal or absent lymphatic or venous drainage of the bone, perhaps due to a local defect in metaphyseal bony growth or remodeling.9 This elevated pressure may explain success in surgical treatment strategies involving decompression and/or restoration of local circulation.10–13 Still other researchers have identified elevated levels of prostaglan-dins and oxygen-free-radical scavengers within these lesions, which may cause bone resorption; this observation supports the concept that corticosteroid injection may be used for treatment.12,14–17

Histologically, cyst walls are lined with a fibrous membrane comprised of giant cells; no endothelial lining has been identified, and thus the term “UBC” is somewhat of a misnomer. Some authors have identified cells resembling type A and B synovial cells within the membrane.8

ABCs are similarly benign cystic lesions that may affect the bones of the upper limb. The lesions contain bloody fluid and are lined with fibroblasts, osteoclast-like giant cells, and reactive woven bone.18,19 Again, the name is a misnomer, as histologically these lesions resemble neither cysts nor aneurysms.

In the majority of cases ABCs are primary bone lesions, though may appear secondarily from preexisting osseous lesions in up to 30% of cases. With an estimated incidence of 1.4:1,000,000, ABCs are most common during the second decade of life.20 Indeed, primary ABC rarely occurs in patients over 30 years of age. While the long bones of the lower limb are most commonly affected, ABCs may appear in the humerus and other bones of the upper extremity. In a retrospective multicenter study of 156 children with primary ABC, the humerus was found to be the fourth most commonly involved bone. The clavicle, radius, and metacarpals were less common.21,22

The etiology of ABCs remains unknown. A number of theories have been proposed, including the notion that impaired local circulation results in elevated venous pressures and enlarged vascular disturbances within the affected bone.23 Other theories have implicated prior trauma as an inciting event. It is possible that trauma or changes in local vascularity lead to hemorrhage, inflammation, and increased osteoclastic activity, which in turn results in further bleeding.24

Recently there has been further work into the genetics of these lesions. Genetic translocations (17p11-13 and 16q22) have been identified in some ABCs, perhaps resulting in CDH11 or USP6 oncogenic upregulation.25

Clinical Evaluation

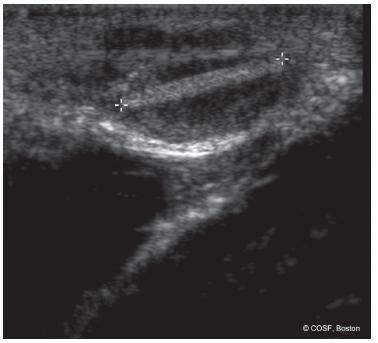

In cases of benign tumors, patients will typically present for evaluation of a visible and palpable mass. Often these masses are asymptomatic and of uncertain chronicity. A careful history is taken, with particular emphasis on identifying any prior penetrating or blunt trauma and eliciting any information that might be concerning for infection. Physical examination allows for identification of the mass and characterization of its size, consistency, mobility, tenderness, and association with overlying skin or vascular changes. The diagnosis may often be made based on simple history and examination. For example, a firm, mobile, subcutaneous nontender cystic mass at the palmodigital flexion crease of the digit is characteristic of a retinacular cyst, whereas raised, nontender, papular masses over the dorsal aspects of adjacent digital tips in a toddler is characteristic of an infantile digital fibroma. In cases of bony involvement, such as seen with enchondroma, radiographs will also have distinct features consistent with the underlying diagnosis. Soft tissue lesions, as well as retained radio-lucent foreign bodies, may be visualized with ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 49-2). With careful clinical evaluation and experience, the diagnosis of most benign tumors can be made based upon clinical grounds.

FIGURE 49-2 Ultrasound of the left hand in a 10-year-old boy with a painful first web-space mass. Findings demonstrate a 1.5-cm splinter in the subcutaneous tissues.

Patients with a UBC of the proximal humerus do not have palpable or visible masses and therefore present in one of two ways. In some patients, the radiographic diagnosis of UBC is made incidentally on shoulder x-rays taken during the evaluation of an unrelated traumatic event. These patients are typically asymptomatic and unaware that the lesion exists. There is no pain, tenderness, or distal neurovascular compromise. Similarly, these shoulders are usually without deformity or physical impairment. Other patients will present with a pathologic fracture of the proximal humerus through the UBC.

The characteristic radiographic appearance of UBCs makes the diagnosis fairly straightforward. The classic UBC is a centrally located, radiolucent, marginated lesion of the metaphysis. In general, the diameter and boundaries of the UBC do not exceed the width of the adjacent physis. Often, a thin radiopaque line is seen within the cyst, the so-called fallen fragment sign, representing a thin cortical fragment that has fractured and settled into the middle of the cyst26 (Figure 49-1).

Patients with an ABC similarly present in one of two fashions. Some patients will present with a cystic lesion identified incidentally on plain radiographs taken for evaluation of a traumatic or other unrelated condition. Other patients will present after pathologic fracture through an existing ABC.

While x-rays of ABCs may appear similar to those of UBCs, there are a number of distinguishing radiographic features characterizing ABCs. Lesions are cystic and often expansile, with dimensions exceeding the width of the adjacent physis. Endosteal scalloping and periosteal elevation are common, giving the lesion the so-called soap bubble appearance. Septa and multiloculated lesions are common. Use of MRI will often confirm the diagnosis, demonstrating fluid-fluid levels within the cyst, along with internal septae.27

Surgical Indications

In general, surgical indications for benign tumors of the hand and upper limb include (1) persistent mass of unclear etiology for which a histopathologic diagnosis is desired; (2) pain and/or functional limitations due to the hand mass; (3) progressive or functionally limiting deformity; and (4) pathological or impending pathological fracture.

The primary indication for surgical treatment of UBCs is the presence of a large lesion associated with prior or impending pathologic fracture. When UBCs are identified incidentally on plain radiographs, quantification of pathologic fracture risk may be performed via quantitative computed tomography28 This information is helpful to patients, families, and providers when weighing the risks and benefits of surgical intervention.

Similarly, indications for surgical intervention for ABCs include the need for diagnostic tissue to establish a diagnosis, pain, and impending or prior pathologic fracture.

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Nonoperative Treatment of Benign Masses

Nonoperative Treatment of Benign Masses

He had the ability of taking a bad situation and making it immediately worse.

—Branch Rickey, on Leo Durocher

Observation is always the first line of treatment for benign tumors of the pediatric hand and upper limb. For many patients and families, education and observation are all that is needed. In many instances, such as with retinacular and ganglion cysts, spontaneous resolution may occur.29

In other situations, the natural history is one of spontaneous resolution, and surgical intervention may only worsen the clinical situation. Indeed, there are some clinical entities that increase in size and spread with surgical stimulus. Infantile digital fibroma is an example of such a lesion. A benign condition thought to be due to proliferation of myofibroblasts, infantile digital fibromas classically present as firm, plaque-like papules over the dorsolateral aspect of the digital tips (Figure 49-3). The presence of paranuclear cytoplasmic inclusion bodies and the clinical observation that these lesions often affect contiguous skin surfaces of adjacent digits have implicated a possible viral etiology for this lesion.1,30 Still others have theorized that abnormal regulation or expression of transforming growth factor-beta during developmental digital separation may lead to this condition.30,31 Given the propensity of this benign condition to regress spontaneously during the first decade of life, as well as its tendency to recur after attempted surgical excision, observation is the preferred treatment. In rare situations, biopsy may be performed to confirm the diagnosis.

FIGURE 49-3 Infantile digital fibroma. A: Dorsal aspect of a 2-year-old child with infantile digital fibroma. Note the characteristic contiguous lesions affecting the dorsoradial aspect of the small and dorsoulnar aspect of the ring finger. B: Alternate view depicting the size of the lesion.

Nonoperative Treatment of a UBC

Nonoperative Treatment of a UBC

Nonoperative management of a UBC is appealing. In the asymptomatic patient with an incidentally diagnosed UBC, observation is often the treatment of choice, particularly given the expectation of UBC resolution with continued skeletal maturity32 Indeed, most believe these cysts will progress from an active to quiescent to involutional stage as a part of their natural history

In patients with symptomatic UBCs or those presenting in the setting of pathologic fracture, there are some instances in which the cysts will spontaneously resolve during or after fracture healing. However, these instances of spontaneous healing are rare, occurring in <15% of cases.2,33,34 Perhaps this is due to the fact that only a minority of fractures occur during the involutional stage.

Ultimately, the clinical decision making regarding nonoperative treatment is clouded by the lack of information regarding the natural history of these lesions. Little reliable prognostic information can be obtained by cyst (size, location, associated fracture) or patient (age, gender, skeletal maturity) characteristics.32 This is further complicated by the recurrence rates seen after attempted surgical treatment.

Similarly, observation of ABCs may be considered for asymptomatic patients.27,35 This should be an active process, however, involving serial clinical examinations and radiographs to monitor for symptoms and/or radiographic progression. Furthermore, when the diagnosis remains unclear, biopsy for tissue diagnosis should be considered. This is particularly relevant given that ABCs may arise from or resemble other malignant tumors (e.g., telangiectatic osteogenic sarcoma).36

Aspiration and Injection of UBC

Aspiration and Injection of UBC

If at first you don’t succeed, you are running about average.

—M. H. Alderson

Although the true cause of UBC remains unknown, the elevated prostaglandin levels found have supported the concept that steroid injection may be used for treatment. Even with the encouraging data regarding steroid injection, multiple injections may be required to achieve cyst resolution, and the recurrence rate remains.14,37–40

Indeed, the risk of persistent or recurrent cyst has been cited between 41% and 84% after single injection.14,41–45

In addition to aspiration and corticosteroid injection, other adjuvant measures have been proposed to increase the success rates. Mik et al.46 have proposed aspiration, intramedullary decompression, and packing the lesion with medical-grade calcium sulfate pellets. Autologous bone marrow injections have also been used, with reported success rates of up to 75%.44,47–50 Still others have utilized autologous bone marrow aspirate and demineralized bone matrix in addition to steroid injection.45,51 Indeed, with this combination of agents, success rates approach 50% after a single treatment.

Bone morphogenetic protein is not used, based upon prior reports of profound pain, swelling, and inflammation after injection for bone cysts.52

Currently, we use steroid injection combined with bone marrow aspirate and demineralized bone matrix for first line UBC treatment.

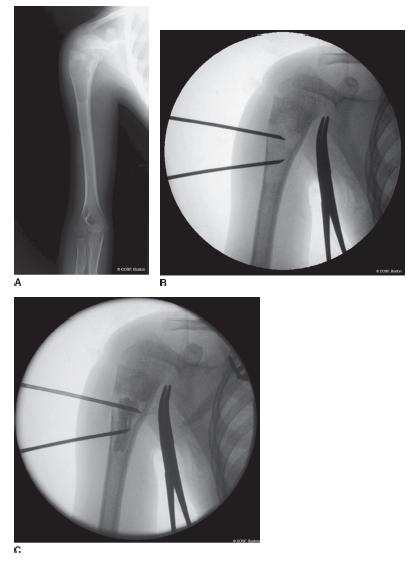

The procedure is performed under general anesthesia with fluoroscopic guidance (Figure 49-4). Patients are placed in the supine position on a radiolucent table, and the entire upper limb and ipsilateral iliac crest region are prepped and draped into the surgical field. After localization of the lesion, two 13-gauge bone marrow aspiration needles (Lee-Lok, Lee Medical, Plainsboro, NJ) are placed percutaneously through the humeral cortex into the cyst: one proximal and one distal. Aspiration of the intralesional fluid is performed, and, if the diagnosis is in question, the fluid is sent for cytology and pathohistological evaluation. Half-strength radiographic contrast (Optiray) is then injected into the cyst, both to confirm accurate needle placement and to characterize the morphology of the lesion. Particularly in the setting of prior pathological fractures, these “unicameral” lesions may be loculated and septated. Following this, 40 to 80 mg of methylpredniso-lone acetate (Depo-Medrol, Pfizer, New York, NY) combined with 5 mL of demineralized bone matrix (Grafton DBM Gel, Osteotech, Inc., Eatontown, NJ) and 5 to 10 mL of bone marrow aspirate harvested from the iliac crest is mixed and injected into the cyst. Simple adhesive bandages may be placed, and sling immobilization is utilized for comfort only postoperatively.

FIGURE 49-4 Aspiration and injection of a proximal humeral UBC. A: Preoperative radiograph of a 7-year-old male who had sustained three prior pathologic fractures through a bone cyst, with no radiographic resolution after fracture healing. B: Intraoperative fluoroscopy depicting placement of needles into the proximal and distal aspects of the cyst. C: Radiopaque contrast is placed, confirming appropriate needle placement and ruling out the presence of septae/loculations. The cyst was subsequently injected with a combination of corticosteroid, autogenous bone marrow aspirate, and demineralized bone matrix.

Steroid injections have not been shown to be successful in cases of ABC.14,24,27 Some early reports have suggested that alcohol or calcitonin injections may be efficacious for ABCs; however, we do not currently utilize injections for the treatment of ABCs.53,54

Mass Excision

Mass Excision

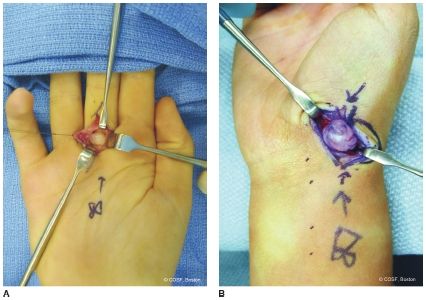

There are a host of situations in which simple mass excision is indicated and will provide confirmation of diagnosis as well as improvements in pain and functional limitations. While each clinical entity and individual patient is different, a number of unifying surgical principles apply. First, longitudinal incisions should be used whenever the diagnosis is in doubt. Second, critical neurovascular structures should be identified proximal and distal to the mass and protected whenever possible. Furthermore, every effort should be made to obtain a complete marginal excision in cases of benign lesions, to maximize clinical results and minimize recurrence risk. In our experience, simple excisions of benign ganglions, retinacular cysts, vascular malformations, and other well-circumscribed soft tissue lesions are done effectively with <10% risk of recurrence (Figure 49-5).

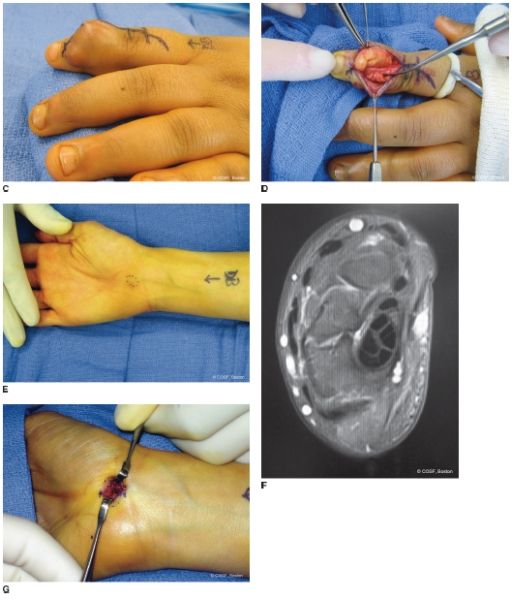

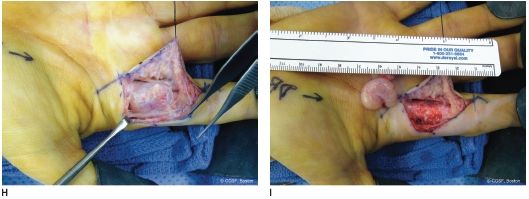

FIGURE 49-5 Clinical examples of surgical excision of common benign hand and upper limb masses. A: Intraoperative photograph of a symptomatic retinacular cyst of the long finger in a 14-year-old right hand–dominant rower and lacrosse athlete. B: Large volar radial wrist ganglion cyst, excised due to persistent symptoms of pain and difficulty resting the pronated hand on flat surfaces. C, D: Preoperative clinical and intraoperative appearance of a giant cell tumor of tendon sheath, which affected the extensor mechanism of the index finger in a 6-year-old male. E, F: Clinical photograph and preoperative axial MRI image of a symptomatic subcutaneous vascular malformation. G: Intraoperative appearance during surgical excision of the superficial venous malformation. H, I: Intraoperative photographs during excision of a symptomatic mass of the index finger. Subsequent pathology was consistent with a peripheral schwannoma. Note that the mass could be removed while preserving the radial digital nerve to the index finger.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree