Bariatric Surgery in Adolescents

Childhood obesity continues to be an increasingly prevalent and progressive disease with limited treatment options. Not only have increasing numbers of children and adolescents been affected, but the average weight of obese children continues to soar. In the USA alone, it is estimated that approximately 4% (over 2 million children and teens) are extremely obese (BMI > 99th percentile).1 Evidence from clinical trials show that behavioral weight management may have longer-lasting effects in younger children compared with adults, but good long-term outcomes are rare. These conventional treatment approaches are not effective for most who suffer with severe obesity,2–5 leading to the consideration of surgical weight loss options for select adolescents. A number of important factors must be considered when contemplating bariatric operations in adolescents. Surgical weight loss results in significant improvement, if not resolution, of most obesity-related comorbidity in adults.6 Short-term results suggest that this also is true for adolescents,7–11 but little is known about long-term efficacy and potential adverse consequences to an adolescent with the lifelong restriction of calories and certain micronutrients. The issue of recidivism and the potential multigenerational consequences necessitate that considerable care and deliberation be applied to decision-making concerning surgical weight management in this population.

Definitions

Obesity specifically refers to the condition of having excess body fat. Measurement of body mass index (BMI) is a reasonably accurate method for predicting adiposity, is reproducible in the clinical setting, and can be used as a screening tool.12–15 In children and adolescents, physiologic increases in adiposity, height, and weight during growth are expected. Given that childhood obesity is a global problem, it should be noted that there are ethnic and racial variations in onset, prevalence, and severity of the metabolic consequences of childhood obesity. Growth charts that are typically used to define obesity are age and gender specific.16–18

The terms overweight (BMI for age and gender >85th percentile), obese (BMI for age and gender >95th percentile), and extreme obesity (BMI for age and gender >99th percentile) have been used to refer to the increasing weight problem in children.18–20 The 85th and 95th percentiles of BMI for age were chosen mainly because these percentile boundaries approximate the BMI in young adults of 25 kg/m2 (overweight) and 30 kg/m2 (obese), respectively. Whereas more than 32% of adults in the USA are obese, about 18% of children and adolescents are obese, a prevalence that has more than tripled in the past two decades.1,21 Regarding extreme obesity, adolescent boys and most adolescent girls younger than age 18 with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 are above the 99th BMI percentile.1,18 Increasing metabolic risks associated with higher BMI for age, especially greater than or equal to the 99th BMI percentile, have been found when compared with lower levels of obesity.1 In addition, because all children with a BMI above the 99th percentile become obese adults (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) and because obese adults who were obese as children have more health complications and a higher mortality,1,22,23 bariatric surgical procedures in the mature adolescent may be a reasonable option for weight reduction that may well reduce the risk of obesity-related morbidity and early mortality.24

Consequences of Adolescent Obesity

Adolescent obesity is a multifaceted disease with serious immediate, intermediate, and long-term consequences.25,26 Critical periods exist between preconception and adolescence during which the risk of development of obesity is increased.27 Important risk factors for childhood and adolescent obesity are (1) low birth weight;28–31 (2) bottle feeding;32,33 (3) early adiposity rebound;34–38 (4) having a diabetic mother;39,40 (5) puberty;41–43 and (6) parental obesity.44–47 Knowledge of these risk factors for adolescent obesity gives insight into the genetic and environmental factors that result in obesity. With few exceptions, little understanding exists about which risk factors portend the development of extreme obesity.48–50

Associated with the remarkable increase in the prevalence of pediatric obesity is a parallel increase in the severity of obesity and in obesity-related chronic diseases. These diseases have an onset at a younger age and carry an increased risk for adult morbidity and mortality.51–55 Childhood obesity has adverse social and economic consequences.56–58 Numerous comorbid conditions exist in childhood obesity, affecting every major organ system.

Guidelines for Performing Bariatric Surgical Procedures in Adolescence

Patient Selection Criteria

National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines suggest that it is reasonable to consider weight loss surgery for adults with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or greater in the presence of severe obesity-related comorbidities (e.g., sleep apnea, diabetes, joint disease severe enough to require joint replacement) or a BMI of 40 kg/m2 in the presence or absence of comorbidities.59 Although these criteria have remained unchanged since 1991, investigators at several institutions have used lower BMI guidelines for studying the effect of weight loss surgery on adults without adverse consequences. Data support the use of lowered BMI guidelines for patients with severe comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes, which are responsive to weight loss.60

Recently published best practice guidelines consider a BMI greater than or equal to 35 kg/m2 with significant comorbidities or BMI of 40 kg/m2 with other comorbidities as factors to be used in the selection of adolescents who are most likely to benefit from bariatric surgical procedures.61 Physical maturity should be documented by either history and physical examination or radiographic study, thus generally limiting surgery to those individuals over the age of 12 years.

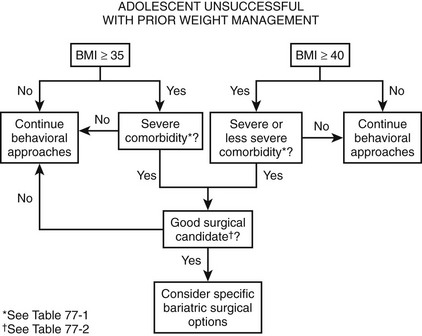

Specifically, when a teenager has reached physical maturity and has achieved a BMI greater than or equal to 35 kg/m2 with serious obesity-related comorbidity, and surgical therapy will be predictably successful in reversing the obesity and comorbidity, it is reasonable to consider a surgical treatment before adulthood. This is the case for adolescents with type 2 diabetes mellitus, pseudotumor cerebri, sleep apnea (apnea–hypopnea index >15), and severe steatohepatitis. For adolescents with less severe comorbidities or risk factors for long-term diseases, for which there is no disadvantage of waiting until adulthood, it is recommended that a BMI of 40 kg/m2 be used as a threshold for operative intervention. These comorbidities include, among others, mild obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), hypertension, milder forms of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), impaired quality of life, insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, or dyslipidemia.61 Figure 77-1 outlines a suggested algorithm for management.

Bariatric Programs for Adolescents

For highly motivated adolescents with comorbid conditions (Box 77-1) who have been unsuccessful with prior dedicated attempts at weight loss (generally at least 6 months), bariatric surgery should be considered as a therapeutic option. Young patients being considered for bariatric surgical procedures should be referred to a specialized center with a multidisciplinary bariatric team with pediatric expertise. Such a team is equipped for the sometimes difficult patient selection decisions and can provide long-term follow-up and management of the unique challenges posed by the severely obese adolescent. Guidelines have been established by the American Society for Bariatric Surgery (ASBS) (www.asbs.org), and the American College of Surgeons (ACS) that define such teams to include specialists with expertise in obesity evaluation and management, psychology, nutrition, physical activity, and bariatric surgical treatment.62 Depending on the individual needs of the adolescent patient, additional expertise in general pediatrics, adolescent medicine, endocrinology, pulmonology, gastroenterology, cardiology, orthopedics, and ethics should be readily available. At Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, the patient review process is similar to that used in our multidisciplinary oncology and transplant programs.63 This review by a panel of experts from various disciplines results in specific treatment recommendations for individual patients, including appropriateness and timing of possible operative intervention.

Factors Influencing Timing of Surgery

Physical Maturation

The timing for surgical treatment of extremely obese adolescents remains controversial and depends, in most cases, on the compelling health needs of the patient. However, certain physiologic factors must be considered in treatment planning. There is a theoretical concern about the impact of significant caloric restriction on the attainment of a genetically predetermined adult stature. Physiologic maturation is generally complete by sexual maturation (Tanner) stage 4.64 Skeletal maturation (adult stature) is normally attained by the age of 13 to 14 years in girls and 15 to 16 years in boys.65 Overweight children generally experience accelerated onset of puberty. As a result, they are likely to be taller and have advanced bone age compared with age-matched nonobese children.

If uncertainty exists about whether adult stature has been attained, skeletal maturation (bone age) can be objectively assessed with a radiograph of the hand and wrist.66 If an individual has attained more than 95% of adult stature, it is unlikely that a bariatric procedure would significantly impair completion of linear growth.67 For those who have not yet reached or nearly reached their predicted adult stature, one must balance the risks of growth delay due to caloric restriction against the potentially more significant risks of progression of obesity-related comorbid conditions if surgery is delayed.

Psychological Maturation

Adolescent psychological development also impacts the ability to participate in surgical decision-making and postoperative dietary compliance. Cognitive development refers to the development of the ability to think and reason. At any given age, adolescents are at varying stages of cognitive, psychosocial, and biologic maturity. The more mature adolescent who can reason and think abstractly is better able to consider the consequences of taking or not taking nutritional supplements or of following and adhering to the prescribed medical and nutritional regimens that are necessary for lifelong success (e.g., maintenance of weight loss and prevention of avoidable nutritional complications) after bariatric procedures.68

Before any decision for an operation is made, all candidates should undergo a comprehensive psychological evaluation.69 Goals of this evaluation include:

• To determine the level of cognitive and psychosocial development, primarily to judge the extent to which the adolescent is capable of participating in the decision to proceed with the intervention

• To identify past and present psychiatric, emotional, behavioral, or eating disorders

• To define potential support for, or barriers to, regimen compliance, the family readiness for surgical treatment, and the required lifestyle changes (particularly if one or both parents are obese)

• To assess reasoning and problem-solving ability

• To assess whether reasonable outcome expectations exist

• To assess family unit stability and identify psychological stressors or conflicts within the family

• To determine whether the adolescent is autonomously motivated to consider bariatric surgical treatment or whether any element of coercion is present

Unfortunately, no ‘relative value scale’ exists that would enable one to assign appropriate significance to the wealth of information (subjective and objective) obtained in the psychological evaluation. However, during a comprehensive assessment, we have found that a complete psychological assessment is very helpful for team decision-making and that generally good team agreement is reached about whether a particular patient has a majority (or conversely a minority) of the attributes of a good candidate for bariatric surgery (Box 77-2).

Surgical Options

In 1991, the NIH Bariatric Consensus Development Conference established parameters that led to a more uniform application of bariatric operations for adults. After that conference, an increase in the use of these procedures occurred. This conference concluded that, at that time, insufficient data existed to make recommendations about bariatric surgical treatment for patients younger than 18 years. Fortunately, outcome data are emerging for the adolescent age group, and adolescent bariatric research is now receiving some attention at the NIH. Indeed, multiple studies with an adolescent bariatric focus have now been funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases to examine various outcomes of adolescent weight loss surgery. The largest and most comprehensive study to date, a multicenter research consortium called Teen-Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (TEEN-Labs), has been formed that includes investigators at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, Texas Children’s Hospital, Children’s Hospital of Alabama, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, and the University of Pittsburgh. Recruitment for this study is now complete with the anticipation of numerous outcome papers to be published from the data set in the very near future. More information about this research consortium can be obtained on the website www.cchmc.org/teen-LABS.

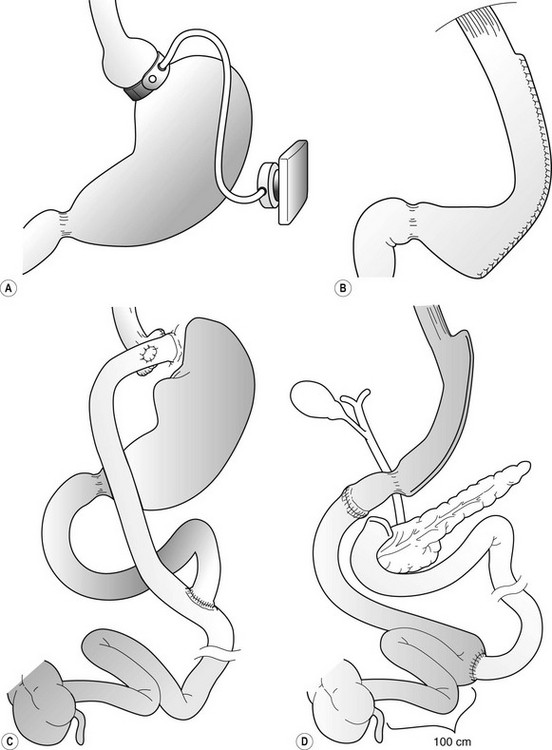

Of the many procedures that have been advocated for weight loss, the operations that have been used primarily can be classified as either purely restrictive or a combination of restriction and malabsorption (Fig. 77-2). The laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (AGB) and laparoscopic vertical sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) are purely restrictive procedures, and the degree of weight loss with these operations in adults has generally been satisfactory. The LSG is a relatively new operation that produces significant initial weight loss with low operative risk in both adult70,71 and pediatric studies.72 Because it likely does not affect micronutrient absorption, it may be a safe alternative with fewer nutritional risks than Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), and also may avoid device-related long-term risks inherent in the AGB procedure.

FIGURE 77-2 Operative procedures for weight loss that are performed laparoscopically. (A) Adjustable gastric band (AGB). (B) Vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG). (C) Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB). (D) Duodenal switch operation.

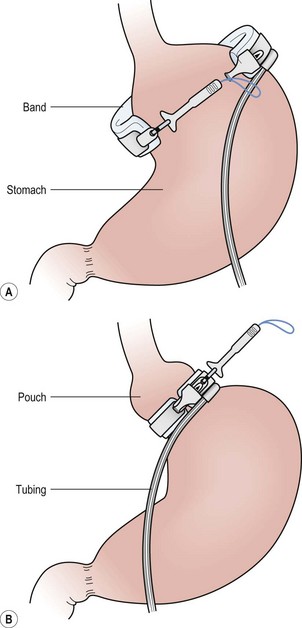

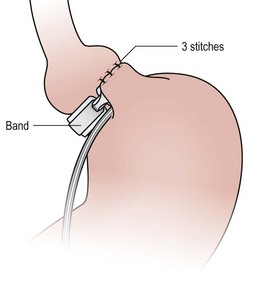

There are good reasons to think that adolescents may be better served by purely restrictive options such as the AGB73 (Figs 77-3 and 77-4) or LSG72 (Figs 77-5 and 77-6). Although nutritional deficiencies are not as likely to develop from the purely restrictive operations as compared with diversionary operations (gastric bypass, duodenal switch), these operations still impair overall energy intake significantly. This may lead to impaired intake of important vitamins and minerals if not adequately supplemented. With operations that do not transect the gastrointestinal tract, there is less risk and a reportedly lower mortality risk compared with gastric bypass.74 A specific patient group for which one might suspect that a purely restrictive operation would be well suited is the younger adolescent, or even preadolescent, with a significant, progressive comorbid condition (e.g., type 2 diabetes, OSAS, or pseudotumor cerebri). However, these patients have the greatest potential for noncompliance with postoperative nutritional recommendations.

FIGURE 77-3 (A) After careful dissection in the retrogastric space, the adjustable gastric band is pulled behind the stomach with a grasping instrument. (B) The instrument is then placed through the buckle, and the locking portion is grasped and pulled through the buckle and locked in place.

FIGURE 77-4 Plication of the anterior wall of the stomach over the gastric band is accomplished with three or four sutures using 2-0 permanent suture. These sutures should be deep and full thickness. It is important to remove the orogastric tube before placement of these sutures so that the tube is not incorporated in these plication sutures.

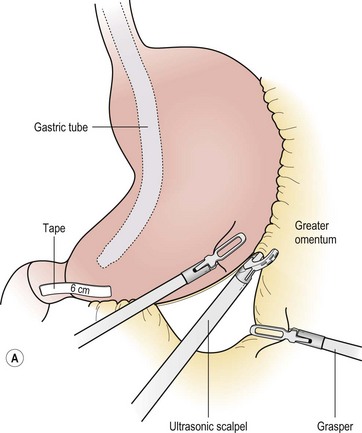

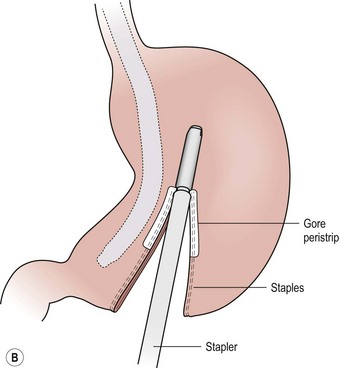

FIGURE 77-5 (A) For the LSG the greater omental attachments and the short gastric vessels are taken down along the entire extent of the greater curvature of the stomach using the ultrasonic scalpel. This dissection is started 6 cm from the end of the pylorus. (B)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree