Arboviruses

Jason Brophy and Elizabeth Lee Ford-Jones

Arboviruses (or arthropod-borne viruses) are a heterogeneous group of viruses that share the same usual route of entry into humans: via the bite of an infected mosquito, tick, sandfly, or other arthropod.1,2 The life cycle of most arboviruses is characterized by the ability of the virus to replicate in both an arthropod vector and a vertebrate “natural” host (usually birds or small mammals) and by transmission between these two organisms at the time of the arthropod’s bite (eFig. 305.1  ). This cycle leads to establishment or maintenance of the virus in a given ecosystem. Humans or domestic animals are only “incidental” hosts for many species of arboviruses, as infection in such hosts (although capable of causing disease) is often a dead-end for the virus due to viremia being too low or too transient to contribute to maintenance of the cycle of transmission. Some viruses are specific to a single genus or species of insect, while others are transmissible by multiple vectors. In addition, some arthropods are capable of transovarial transmission, wherein their eggs (which sometimes overwinter and hatch in spring) are infected with the virus, allowing viral maintenance in areas of colder climate.

). This cycle leads to establishment or maintenance of the virus in a given ecosystem. Humans or domestic animals are only “incidental” hosts for many species of arboviruses, as infection in such hosts (although capable of causing disease) is often a dead-end for the virus due to viremia being too low or too transient to contribute to maintenance of the cycle of transmission. Some viruses are specific to a single genus or species of insect, while others are transmissible by multiple vectors. In addition, some arthropods are capable of transovarial transmission, wherein their eggs (which sometimes overwinter and hatch in spring) are infected with the virus, allowing viral maintenance in areas of colder climate.

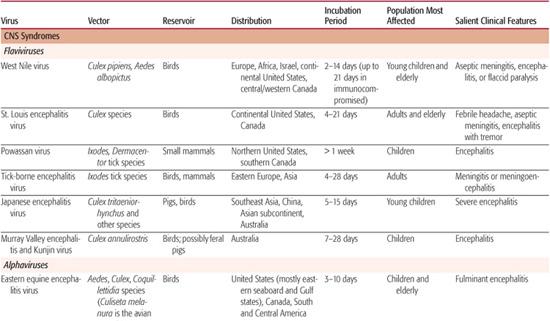

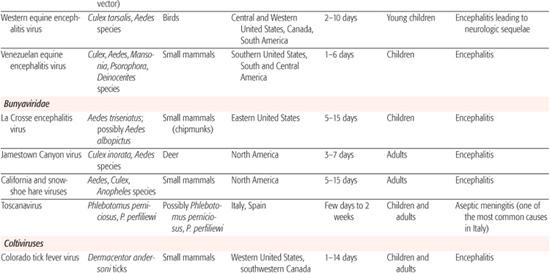

Arboviruses generally produce 1 of 4 clinical syndromes: (1) central nervous system (CNS) disease, (2) febrile illness with rash, (3) arthropathy, or (4) hemorrhagic fever syndrome.1 In North America, encephalitis is the most commonly diagnosed manifestation of arboviral infection, with several viruses producing sporadic disease as well as outbreaks of infection each year. Table 305-1 provides a list of arboviruses presenting with different symptom complexes, and details the vector, reservoir, distribution, incubation period, and the population most affected.

CLASSIFICATION OF ARBOVIRUSES

The term arbovirus refers only to viruses in which the mode of infection is by the bite of an infected arthropod. This artificial grouping includes dozens of viruses from a number of different families and genera, including mainly the Flavivirus genus, the Alphavirus genus, the Bunyaviridae family, and the Reoviridae family (Coltivirus genus). These viruses differ phylogenetically and structurally but nonetheless produce similar types of illness.

Flaviviruses

These are a large group of viruses with worldwide distribution, over 30 of which cause disease in humans.3,4 The prototype of the genus is yellow fever virus, from which the genus name is derived (flavus being Latin for “yellow”). Eight antigenic groupings have been found, the most important of which are the Japanese encephalitis complex (which includes Japanese encephalitis, St. Louis encephalitis, West Nile, and Murray Valley fever viruses); the dengue complex (dengue viruses 1–4); the tick-borne virus complex (Central European encephalitis [more recently renamed tick-borne encephalitis], Russian spring-summer encephalitis, louping-ill, Powassan, Kyasanur Forest disease, and Omsk hemorrhagic fever viruses); and yellow fever virus.

Alphaviruses

These are a genus within the Togaviridae family and include a number of medically important arboviruses.5 These can be roughly divided into New World alphaviruses, which cause CNS disease and include eastern equine, western equine, and Venezuelan equine encephalitis viruses, and Old World alphaviruses, which are more likely to cause syndromes of fever, rash, and arthropathy (Chikungunya, O’nyong-nyong, Mayaro, Ross River, Sindbis, and Barmah Forest viruses).

Bunyaviridae Viruses

This family includes multiple arthropod-borne viruses as well as viruses transmitted by other modes.6 The main arboviral genera in the Bunyaviridae include the Bunyavirus genus (including the California encephalitis group: La Crosse, California, and Jamestown Canyon viruses); the Phlebo-virus genus (which includes Rift Valley fever virus and Toscana virus); and the Nairovirus genus (which includes Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus). The Hantavirus genus is also in this family; however, these viruses (which cause pulmonary syndromes as well as hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome) are transmitted via direct inhalation of rodent excreta or urine rather than by arthropod bite.

Coltiviruses

These are a genus within the Reoviridae family, which also includes the well-known rotavirus member.7 Coltivirus arboviral species include Colorado tick fever virus as well as a number of other rare members (Salmon River virus, Eyach virus, and Asian members of the Seadornavirus genus such as Banna and Beijing viruses).

SYNDROMES CAUSED BY ARBOVIRUSES

CNS ARBOVIRAL INFECTIONS

CNS ARBOVIRAL INFECTIONS

Arboviral infections can lead to CNS disease of various forms, most commonly including encephalitis, meningitis, and flaccid paralysis. CNS manifestations are usually a rare outcome of infection, with the majority of people developing these infections being asymptomatic or having mild, nonspecific symptoms. This chapter is focued on those infections that most commonly lead to CNS disease in North America and touch on those that are most important globally (tick-borne encephalitis and Japanese encephalitis viruses).

West Nile Virus

West Nile Virus (WNV) was originally discovered in 1937 in Uganda and is maintained in an enzootic life cycle in birds of the Corvidae family (crows, magpies, jays) via mosquito transmission3,8 (see eFig. 305.2  ). Sporadic epidemics and epizootics (spread within animal populations) were previously observed in Israel (1950s), South Africa (1970s), Algeria, Morocco, Romania, Tunisia, Czech Republic, Congo, Italy, Israel, Russia, and France (1990s), but not in North America until 1999. That year, an outbreak of WNV encephalitis cases was reported in New York City with a strain of virus that was genetically indistinct from epidemic strains in Mediterranean countries, suggesting introduction from that area of the world. A simultaneous epizootic was noted in horses and birds at that time. Since 1999, WNV has spread throughout North America and in 2007 was reported in all continental US states (eFig. 305.3

). Sporadic epidemics and epizootics (spread within animal populations) were previously observed in Israel (1950s), South Africa (1970s), Algeria, Morocco, Romania, Tunisia, Czech Republic, Congo, Italy, Israel, Russia, and France (1990s), but not in North America until 1999. That year, an outbreak of WNV encephalitis cases was reported in New York City with a strain of virus that was genetically indistinct from epidemic strains in Mediterranean countries, suggesting introduction from that area of the world. A simultaneous epizootic was noted in horses and birds at that time. Since 1999, WNV has spread throughout North America and in 2007 was reported in all continental US states (eFig. 305.3  and in central and western Canada (Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta).10

and in central and western Canada (Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta).10

Table 305-1. Arboviruses of Importance in North America and Globally

While WNV infection occurs predominantly via arthropod transmission to humans, there have also been rare reports of transmission via blood transfusion, organ donation, and perinatal transmission from an acutely infected mother.9 A seasonal pattern of transmission from July to December has been noted yearly, with the bulk of transmissions taking place during August and September.

After the host is bitten by an infected mosquito, the virus replicates locally in tissue and lymph nodes before resulting in viremia and sometimes crossing the blood-brain barrier to lead to neurologic disease.9,11 The incubation period to development of symptoms is 2 to 14 days but can be as long as 21 days in immunocompromised patients.3,12,13 Only about 20% of individuals will develop symptoms of infection; most of these will develop West Nile Fever, while less than 1% will develop CNS manifestations. West Nile Fever is characterized by abrupt onset of fever, headache, myalgia, weakness, gastrointestinal symptoms (abdominal pain, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea), and sometimes a transient maculopapular rash. Symptoms often last several days and can be followed by a more prolonged period of fatigue and weakness. Other nonneurologic manifestations that have rarely been observed include hepatitis, pancreatitis, myocarditis, rhabdomyolysis, orchitis, bladder dysfunction, and ocular manifestations such as chorioretinitis, optic neuritis, and retinal hemorrhages.

CNS disease most commonly manifests as meningitis, encephalitis, or flaccid paralysis.3,13,14 WNV meningitis produces the usual symptoms of aseptic or viral meningitis, with fever, headache, and neck stiffness, along with the above-mentioned West Nile Fever symptoms; cerebrospinal fluid analysis often reveals a mild to moderate lymphocytic pleocytosis, elevated protein, and normal glucose. WNV encephalitis can be characterized by the additional findings of altered sensorium, seizures, parkinsonian features (bradykinesia, cogwheel rigidity, postural instability, and masked facies), and other movement disorders such as myoclonus, intentional tremor, and bruxism. Viral infection of the anterior horn cells can produce a poliomyelitis-like presentation with an acute, symmetric, flaccid paralysis. WNV infection has rarely been associated with Guil-lain-Barré syndrome. Most patients with WNF or aseptic meningitis recover completely, but patients with encephalitis or flaccid paralysis can be left with residual deficits. The case fatality rate of neurologic disease in adults is 5% to 9% but is less than 1% in children.13,15

St. Louis Encephalitis Virus

St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV) is found exclusively in the western hemisphere and was the leading cause of epidemic flaviviral encephalitis in the United States until the arrival of West Nile virus in the last decade.3 It is found throughout continental United States and parts of Canada (see eFig. 305.4  ). SLEV was first recognized in 1933 in St. Louis, Missouri, and both sporadic cases and focal outbreaks have been observed throughout North America since that time. Similar to West Nile virus, SLEV is maintained in a zoonotic life cycle, with birds as the definitive host, and is transmitted to humans by the bite of Culex species of mosquitoes in the late summer and early fall.

). SLEV was first recognized in 1933 in St. Louis, Missouri, and both sporadic cases and focal outbreaks have been observed throughout North America since that time. Similar to West Nile virus, SLEV is maintained in a zoonotic life cycle, with birds as the definitive host, and is transmitted to humans by the bite of Culex species of mosquitoes in the late summer and early fall.

Less than 1% of SLEV infections are clinically apparent, and 3 main clinical syndromes are observed: simple febrile headache, meningitis, and encephalitis, with the risk of more severe and neuroinvasive disease increasing with age. After an incubation period of 4 to 21 days, onset of symptoms begins with a flulike prodrome of fever, headache, myalgia, fatigue, and sometimes respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms. As with West Nile virus, urological symptoms, including dysuria, urgency, and incontinence, can also be seen in up to 25% of patients.16 Those who develop meningitis usually present with typical features of aseptic meningitis. Encephalitis is most commonly associated with altered consciousness and confusion. Other reported features have included generalized weakness without focal findings, tremulousness, cerebellar signs, cranial nerve deficits, abnormal movements (myoclonus, nystagmus), and, less commonly, epileptiform activity.2,3

Laboratory findings with SLEV infection can include a moderate cerebrospinal fluid mononuclear pleocytosis with elevated protein and increased opening pressure, and hyponatremia can be seen as part of the syndrome of inappropriate secretion antidiuretic hormone.17 Magnetic resonance imaging can show high signal intensity in the substantia nigra. An extended convalescence can be observed in up to half of patients, characterized by asthenia, irritability, tremulousness, sleep disturbance, depressive symptoms, memory loss, and headache.18 Overall mortality is reported as 8% with much higher mortality in the elderly (20%) and much lower in the pediatric population (2%).

Powassan Virus

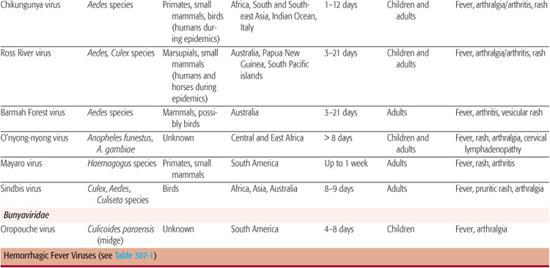

Powassan virus encephalitis occurs rarely. Since its discovery in 1958 when it was isolated from the brain of a 5-year-old child from Powassan, Ontario, who died of encephalitis, it has been found to be a rare cause of encephalitis in North America. It is the only tick-borne flavivirus in the Americas and is related to tick-borne encephalitis virus from East Asia.2While cases of Powassan virus encephalitis have been reported throughout North America and East Asia, overt human disease is felt to be restricted to southern Canada and the northern tier of US states including Wisconsin, Michigan, New York, and Maine (see Fig. 305-1). Persons with a history of outdoor activity are most commonly affected by this virus, but children have been disproportionately represented in the known cases, with one report noting 85% of infections occurring in persons under 20 years of age.

The clinical presentation of Powassan virus disease is not well characterized because of the low number of cases reported.2 The incubation period is at least 1 week from exposure. Reported prodromal symptoms include sudden onset of illness with sore throat, fatigue, headache, and high fever. Encephalitis cases may be characterized by vomiting, prolonged fever, respiratory distress, lethargy, meningeal irritation, and focal neurologic lesions. One reported case had temporal lobe involvement typical of herpes encephalitis. Laboratory findings include cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis, initially polymorphonuclear then lymphocytic, as well as normal glucose and elevated protein. Sequelae, including neurologic abnormalities such as hemiplegia, hypotonia, and spasticity, are common in survivors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree